Sometime shortly after Sept. 11, the prologue became indispensable to writers and editors -- like the smart bomb to Pentagon planners or Cipro to public health officials. With a few pages of lofty prose at the beginning of the text, there wasn't a book around that couldn't be transformed into a meditation on good vs. evil or a testimonial to the innate strength of the American people. Sports biographies, cookbooks, stock market postmortems -- suddenly everything was allegorical.

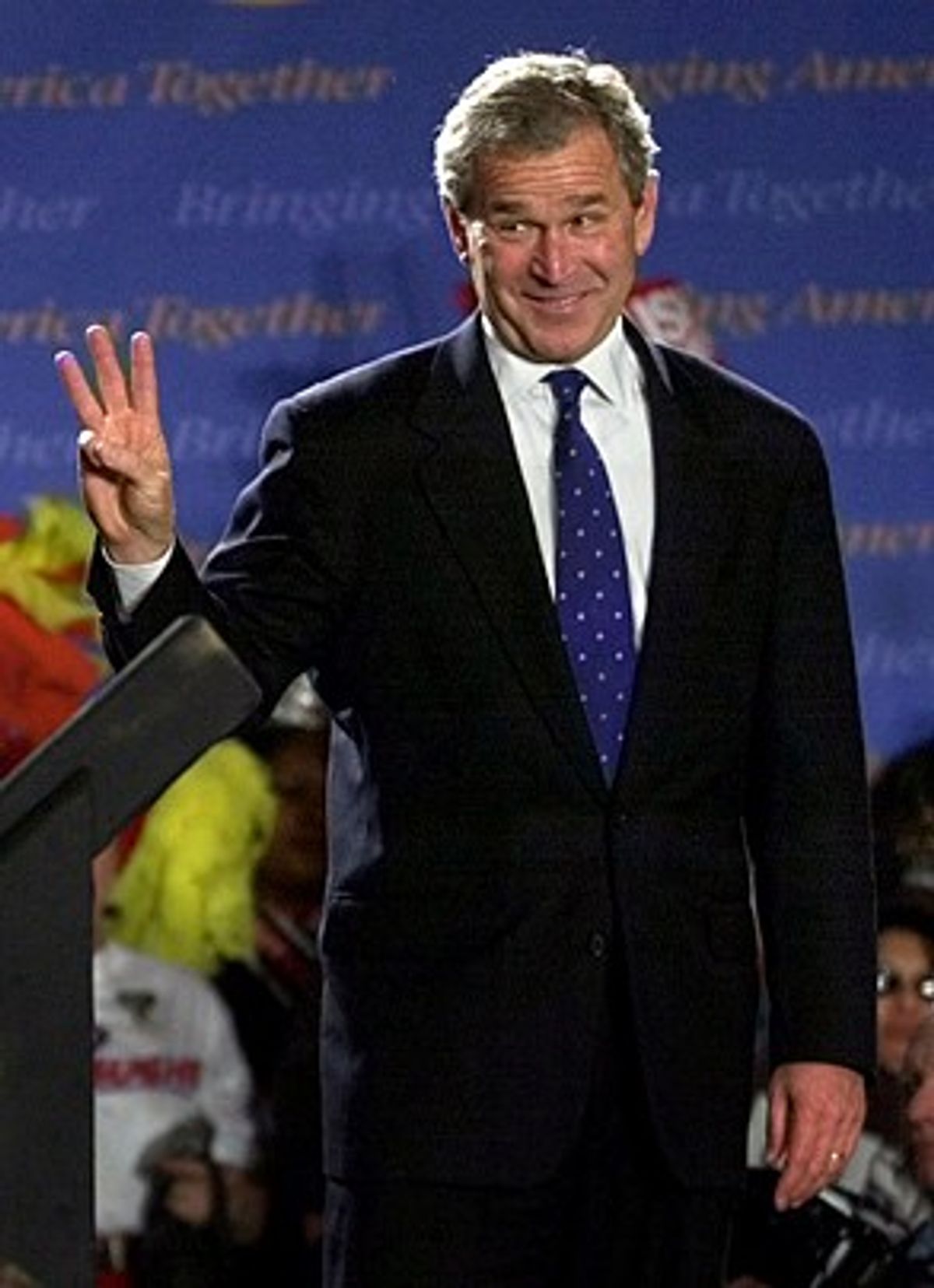

Whatever you think about "Ambling Into History," the latest from New York Times political correspondent Frank Bruni, Bruni and the editors at HarperCollins have grasped this logic impeccably. Bruni's book is mainly a behind-the-scenes account of George W. Bush's presidential campaign, the idea being that Bush is actually a more clever, more caring and more decent guy than most people give him credit for, and that these traits gradually came to the fore over the course of the campaign.

Fine. But Bruni is so determined to connect his book to Sept. 11 that he spends his first dozen pages beating you over the head with it. The implication is that all this hidden cleverness and decentness made Bush the right man for the job once the World Trade Center collapsed. As Bruni puts it, there had always been a side of Bush "that provided more heartening omens for his ability, or at least his determination, to meet the demands that were placed on him after September 11."

Unlike other post-Sept. 11 books, of course, Bruni's doesn't need any of this junk. "Ambling Into History" would have been relevant just by virtue of its providing a closer look at George W. Bush than most of us have ever gotten. For all the president's newfound popularity, no one had a very good idea of what made this apparently unexceptional guy exceptional enough to be president in the first place.

The portrait of Bush that emerges once you peel away all the schmaltz is endearing if not quite reassuring. Bruni catalogs Bush's numerous off-camera antics: hanging a hot airplane towel on his head and playing "peek-a-boo" with Bruni during an interview, flashing goofy expressions to reporters while at a funeral for victims of a church shooting. Ditto Bush's most bizarrely inappropriate comments, as when he barks "Hey Tree Man, get up here!" to a Forest Service official during a press conference on forest fires.

Perhaps more disturbing, Bruni also paints a man who is astonishingly shallow and unreflective. Riffing after the election about his upcoming presidency, Bush can't get beyond his genuine fascination with the White House mess hall: "The dessert menu is unbelievable ... [y]esterday at the Blair House we had this, I'm not even sure, coffee ice cream surrounded by this unbelievable meringue, beautiful meringue." And Bruni informs us that well into his first year in office Bush is "still raving about ... [the] little red button in the private dining room off the Oval Office that he could use to summon the butler." It's Bush as the Tom Hanks character in "Big."

Obviously it's passages like these that explain why the White House has been sweating the book's release for the last several weeks. As the Washington Post's "Reliable Source" column reported in January, Bush communications aides Karen Hughes and Dan Bartlett were apparently so desperate to do preemptive damage control that they repeatedly lobbied Bruni's friends in the media to spill the beans. (A copy of the book's galleys was even stolen from the apartment of one of Bruni's colleagues during a recent party.)

But it turns out that Bruni has a good deal of affection for Bush, and he relates at least as many flattering nuggets as he does embarrassing ones. Among other things, we learn that the president is a pretty clever guy: After fielding questions at a convention of newspaper publishers, Times boss Arthur Sulzberger Jr. among them, Bush asks Bruni if he thinks "Sulzberger worked his way to the top" -- a subtle response to criticism about his ascendance to the Republican nomination.

The Bush we get from Bruni is also humble enough to admit that "[t]here are a lot people who would make great presidents ("the problem," he confesses, "is none of them chose to run"); he's tender enough to be hurt when his daughters don't take an interest in his campaign, and to be moved when they finally offer words of encouragement; and he's kind enough to insist on sending Bruni to his father's birthday party with an autographed card as a present. ("That ought to enhance your standing in the family," he tells Bruni.) "This was the kind of gesture that mattered to him and that he never forgot," Bruni explains. And it's the kind of gesture that makes it hard not to like Bush in the end.

In fact, it's tough to see how Bush comes out the worse for Bruni's book. As embarrassing as some of the low points are, there isn't much that will come as a surprise, at least not to anyone who remembers, say, Bush pronouncing one of Bruni's colleagues a "major league asshole." For that matter, many of these lowlights we've already heard. On the other hand, the high points play sufficiently against the conventional wisdom on Bush that they should make skeptics think twice.

The only bona fide losers here are Karen Hughes, whose Nurse Ratched-like reputation Bruni cements, and Al Gore, who manages to come off as an enormous prick during his lone encounter with Bruni in the book. (Bruni exacts revenge with an anecdote about Gore's overaggressive play at middle infield during a kids' kickball game in St. Louis.)

Where Bruni does overplay his hand -- albeit not quite as badly as with the Sept. 11 motif -- is in reading excessive meaning into these two sides of Bush, the imp and the adult. In the book's press kit, Bruni implies that this dichotomy gives Bush as interesting a personality as Bill Clinton or Richard Nixon. Often he approaches Bush as some sort of enigma, noting more than once that Bush's occasional moments of lucidity made it harder for those accustomed to Bush's usual gobbledygook "to get a real handle on him, on what he might be capable of."

At one point Bruni devotes several evidently earnest pages to deciding whether to accept the campaign's spin on Bush. "We were to believe that he gave succinct public remarks -- because he valued brevity and getting to the point -- We were to believe that he paid limited attention to details and fine points -- because he never wanted to lose sight of the Big Picture -- Was the explanation real," Bruni wonders, "or was it an elaborate attempt at diversion from his failings?" Toward the end of the book Bruni even comes out and says that "[Bush] and his aides seemed to be elaborately constructing a universe around him that deepened the riddle and forbid its solution."

Now, one can understand an author trying to gin up interest in his subject. But a Karamazov brother this president is not. What Bush's generally underwhelming public performances suggest to me is that he's a reliably inarticulate and uninterested guy who every so often gets a talking point straight and who tends to play better in intimate settings. How the campaign's attempts to obscure this makes for some elaborate conspiracy is beyond me.

Still, it's only when Bruni lapses into his all-too-frequent disquisitions on the state of campaign journalism that he starts to grate. At various points in the book Bruni hits on all the familiar journalism-school-seminar themes: Journalists are too often prisoner to simplistic, pre-established campaign narratives (in this case, Bush is dumb, Gore is tedious); journalists too often ignore The Issues in favor of trivia and minutiae (Gore's convention kiss, any major Bush screw-up); journalists spend as much time manufacturing stories as they do reporting them (the R-A-T-S commercial controversy, the debate over the debates); blah, blah, blah.

And yet for all his grumbling about journalists and their narratives, Bruni has invented a pretty tendentious story himself. Much of what Bruni writes is intended to persuade us that Bush "matured" over the course of the campaign. At the story's outset, Bruni depicts a towel-snapping frat boy who can't string two sentences together. By campaign's end, Bush is nothing short of statesmanlike.

As Bruni sums it up: "[Bush] had learned that he could not take so very many things for granted, victory being just one of them, and that he could not take so very many things lightly. He was not a new man, but he was a slightly different one, and maybe a slightly better one." That this new, philosophical Bush was still misbehaving well into the campaign's homestretch -- recall the aforementioned asshole comment -- doesn't seem to bother Bruni. Nor does the several-month-long relapse Bruni describes after Bush assumes the presidency -- cracking juvenile jokes about aides, mouthing messages to reporters during important press conferences.

The truth, as Bruni might say, is more complicated. I don't doubt that Bush is a kind, decent, compassionate man. He's also a man who, like most of us, knows how to act grown-up when the situation demands it. But, short of that, Bruni hasn't convinced me that Bush wouldn't rather be making fart noises with his armpit. (Bruni gives Bush special praise for not yukking it up while looking down at the ruins of the Trade Center. But what 8-year-old couldn't do that?) That may be fine for the lead in some screwball romantic comedy. It may even make you want to talk baseball with the guy over "near-beers." But president? Let's be serious.

Shares