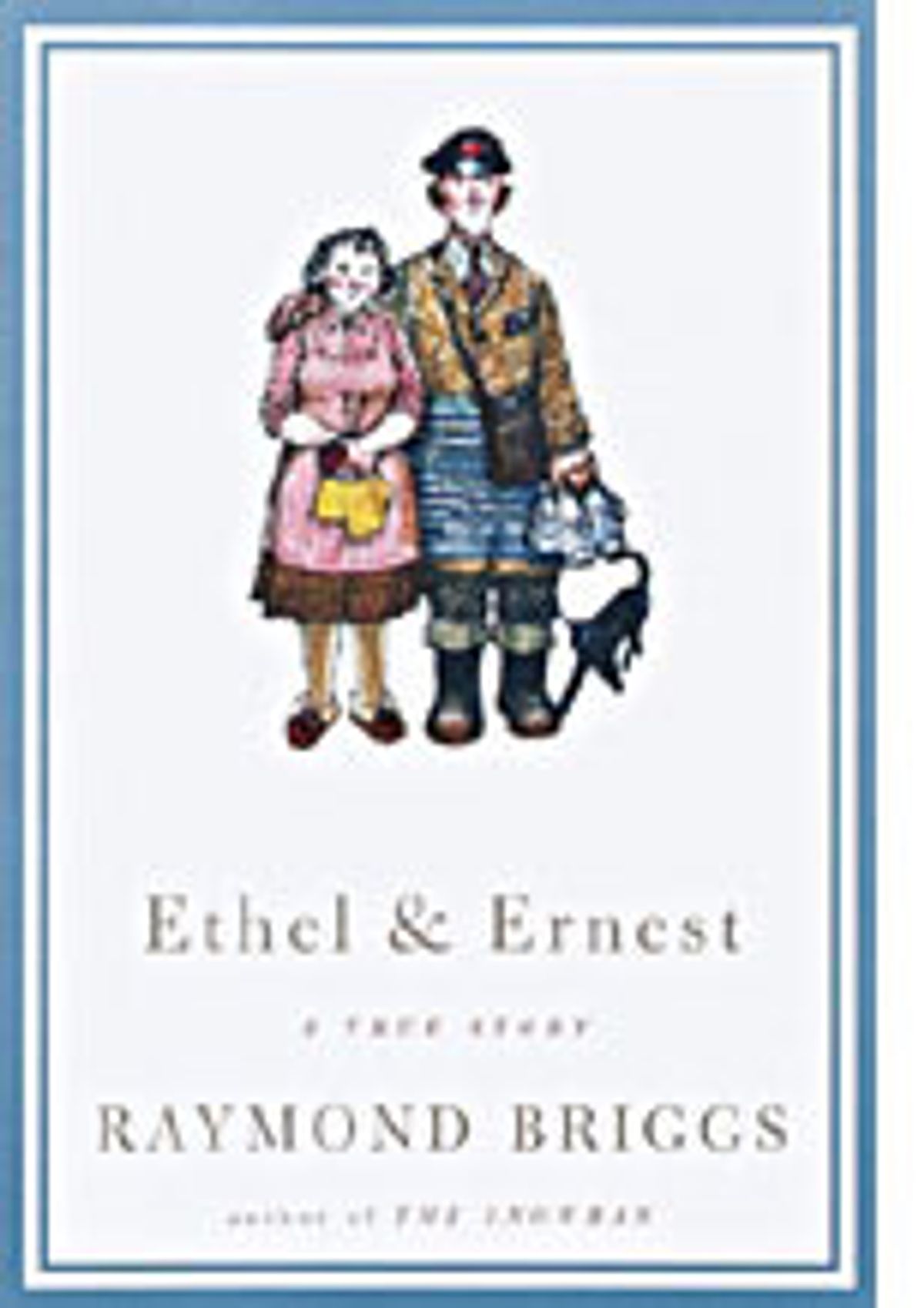

Every few years -- usually after the release of a film version of some classic novel -- a well-respected fiction writer will take to the arts pages to proclaim that movies can never capture the nuances of the printed word. That's nonsense. Images can be as carefully chosen and as delicately nuanced as fiction -- and they certainly are in Raymond Briggs' "Ethel & Ernest," a graphic memoir of the author/artist's parents from their marriage in 1930 to their deaths within a few months of each other in 1971.

In purely technical terms, "Ethel & Ernest" is a small marvel of meaning rendered in color and perspective. Several times Briggs returns to a full-page illustration of the semi-detached house the newlyweds buy in 1930, always with variations. The iron gate that seems so posh when they move in goes for scrap iron during the war. By the time the house is on the market in 1971, the modest green marble pillar by the front door has blackened with age, and bushes have sprung up to the top of the fence. Likewise, the couple's bedroom, unthinkably large to them when they first move in, is rendered to look smaller and smaller, until the ceiling seems to hang just a few feet over their heads. The warm, increasingly worn greens and browns and floral patterns of these rooms find a cruel contrast in the cold starkness of the hospital mortuary where Briggs and his father view Ethel's corpse. A writer could tell us that Ernest, at the end of his 37 years as a milkman, pointedly hangs his certificate of retirement next to his son's diplomas on the sitting-room wall; but showing him putting it there (over his wife's objections) conveys his class pride with beautiful subtlety.

Of course, only very dull people read novels for their technical achievements. All of these subtleties register emotionally. If you're lucky enough to have had the kind of loving mismatch that is Ethel and Ernest's marriage in your own family, you'll recognize their deep attachment instantly. (My grandparents were such a pair. My grandfather died suddenly of heart failure after my grandmother had been bedridden for almost a year, and no one will ever convince me that in some way he didn't will it: Better to die of a stopped heart than a broken one.)

Ethel, a housemaid when Ernest meets her, is a working-class Tory whose greatest fear is being labeled common. Ernest is a proud socialist, Labor to the teeth, from a much rougher background than she can imagine. At times their marriage seems to consist of the succession of the squabbles that ensue when he reads her some item from his evening paper. But they draw together in disappointment when Briggs announces that he intends to go to art school -- an affectionate but, I'm sure, still painful recollection for the artist. Whatever their political differences, they're one in their desire to see him do better than they have.

Ethel can be a snob, as she is when Ernest's stepmother shows up bearing a present of coal and some bottles of stout to see the new baby. But their differences suggest a greater comfort and reassurance. Ethel isn't about to take Ernest's suggestion that they try out their new mattress "in broad daylight," as she says, but she's doubtless flattered by the attention. And while she's forever upbraiding him for some word or phrase she finds too rough, the wink in his delivery suggests he knows that the sweetness inside the roughness is one of the things she loves about him. And Ernest is faithful. In a neat twist on all the old jokes about milkmen, during his rounds a friend offers him a go at the wife whose sexual demands he can no longer handle; Ernest turns down the offer, with no hard feelings on either side. And he knows he can rely on Ethel to be strong when he needs her to be -- as when, serving as a volunteer fireman during the war, Ernest comes home from a harsh night spent pulling dead children out of bombed buildings and breaks down.

Briggs has absented himself from most of the story. During the war he's sent to live in the country (as many of London's children were), and later on he's off doing his military service or at art school. At times that absence is jarring. In one scene, Raymond tells his mother that his wife's schizophrenia will prevent her from ever having children, and we don't know enough about Ethel and Ernest's daughter-

"Ethel & Ernest" imparts, as the best novels do, the sense of lived lives. It's not too much to say you come to love these people, and that as you go along you want not to notice such details as Ernest's new eyeglasses, the deepening lines in the couple's faces, their slackening pace and growing frailty. But because these are details we experience during our own day-to-day lives, during countless meals and evenings by the fire, quarrels and reconciliations, small victories and not so small losses, Briggs' book earns our tears. "Ethel & Ernest" is a just about perfect miniature: small in scale, not in spirit.

Shares