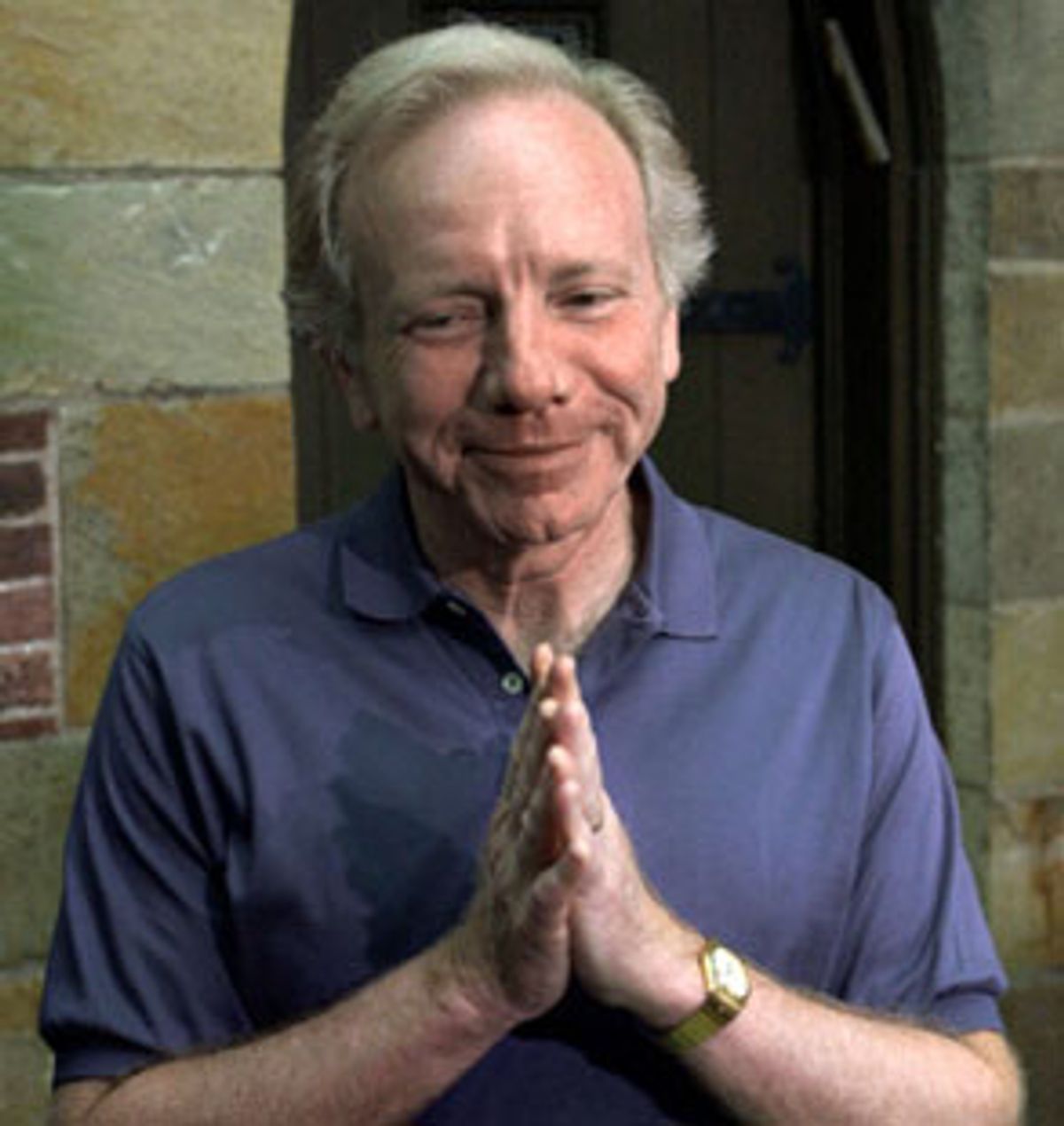

On March 9, Connecticut Sen. Joseph Lieberman -- Vice President Al Gore's pick for running mate, as of Monday -- stood at a press conference with his fellow members of the "Senate New Democrat Coalition" and offered up his group's first tangible legislative proposal.

It was a controversial education bill, offered as an amendment to the Elementary and Secondary Education Act, and it was seen as a moderate, if not downright Republican, proposal for allowing greater flexibility in how local school districts can spend federal money.

"It was a great bill," says a Republican source familiar with the first draft, which Lieberman shared with Republican senators.

"It consolidated hundreds of federal programs into five. It created much more flexibility [for schools to use federal funds] than any of us had ever seen from a Democrat. It tied Title I monies to school performance, it had strenuous teacher testing."

"He showed us a little leg and we were drooling all over the place," the source says.

On the other hand, news of Lieberman's negotiations angered Democratic leaders like Senate Minority Leader Tom Daschle of South Dakota and liberal stalwart Sen. Ted Kennedy of Massachusetts, who reportedly resented not being consulted by Lieberman and his "New Democrat Coalition." In fact, Senate critics said, Lieberman kept the Democratic leadership out of the loop almost entirely.

"They said, 'Please work with us,'" reports a high-ranking Democratic Senate staffer. "But Joe just sort of stuck with his rhetoric. 'We're New Democrats. We favor a new approach. We're tired of the old policies.' And after all, this was a good, sexy political issue."

And it helped him continue a tradition, followed since he was elected to the Senate in 1988, of being a creature apart from the traditional divisions of the Senate.

In order to pull other centrist Democrats on board, Lieberman added funding for school construction to the bill -- with more spending restrictions (i.e., less "flexibility" in what the money could be spent on) than the Republicans wanted. "As he was negotiating with both sides, it began to break apart," reports the GOP source. "He couldn't give us enough, and he couldn't give his side enough."

When Lieberman's legislation came up for a vote as one of the first Democratic amendments in early May, "it was clear that he had acquiesced to the Democratic leadership to let the bill go down early, as a big defeat, to keep the troops in line," the source says.

In the end, Lieberman's bill failed miserably, 13 (all Democrats) to 84. Lieberman got not one Republican vote, and barely a fourth of the 45-member Senate Democratic caucus, to which he belongs.

Lieberman's loser of an amendment isn't atypical for the moderate Democrat seen by liberals in his party as all too eager to work with the GOP. Gore's selection of Lieberman can be seen as shrewd, because Lieberman's bipartisan magnanimity can, and has, prompted nothing but goodwill from Republicans.

"Lieberman is a clever choice for Gore," says Jim Nicholson, chairman of the Republican National Committee. "But it's also a curious choice because there are several key issues where the two men disagree." Nicholson cites Social Security reform, missile defense, school choice, parental notification on abortion, capital gains tax cuts, and tort reform among these. "So we look forward to their first debate," he quips.

So why is the choice "clever"? "Because it's an attempt to bring to the Democratic ticket the integrity, candor and bipartisanship that Gore so clearly lacks," Nicholson says.

According to critics, this is Lieberman's greatest strength -- and most glaring weakness. As the Senate's house moralist, he is valued for his "integrity, candor and bipartisanship" -- and little else.

Lieberman bucks the Democratic party line on a number of high-profile issues. It's almost enough that -- even though he was rated recently as voting with President Clinton more often than his fellow Connecticut Democrat, Sen. Chris Dodd -- he is seen as Republican Senate Majority Leader "Trent Lott and [House Majority Whip] Tom DeLay's favorite Democrat," in the words of Lott spokesman John Czwartacki.

"He would have been my last choice," jokes Connecticut Republican Rep. Chris Shays. "I would have liked Gore to pick [ultra-liberal Minnesota Sen. Paul] Wellstone."

"Joe's clearly the best pick he could have made," Shays says. "I'm happy for Joe, but I'm not happy for us."

"He's a smart pick," says a top GOP Senate staffer. "It reflects well on Gore. First, Lieberman's almost impossible to attack because Republicans mention him constantly -- he's attacked Hollywood, he's an oft-cited Democrat critic of President Clinton's weaknesses. Second, because Lieberman criticized Clinton, with the fact that he's Jewish, makes it look like it took Gore a little gumption to pick him, so the buzz that Gore's risk-averse falls away a bit. Third, he's a decent guy that everybody likes."

Democrats in the Senate agree, though they predictably think less of him for the very reasons Republican give for approving.

"He delights in positioning himself between Democrats and Republicans," says the Democratic Senate staffer. "He's a Democrat that has always liked to say 'I'm not like the other Democrats.'" Though he is heralded for working in a bipartisan way, the staffer says, there is relatively little in terms of legislation that bears Lieberman's name. Indeed, Senate Democrats grouse that Lieberman is an almost unparalleled media hog, though one who gets away with it because of his basset-hound mug, serious and apolitical manner, and smart politics.

Indeed, Lieberman is not like other Democrats. And not only because he is the only Orthodox Jew in Senate history -- the only senator who walks to work on Saturday, the Jewish Sabbath, has a wife named Hadassah and doesn't take to pork unless it's in the form of federal grants to his home state.

In his 12 years in the Senate, Lieberman, 58, has made a name for himself as a moral voice, famous for his rhetoric far more than for his bills -- the Senate's house rabbi. During the campaign-finance scandal hearings led by Sen. Fred Thompson, R-Tenn., in the summer of 1997, Lieberman was hailed as being the least partisan Democrat on the panel, condemning as he did "a clear trail of foreign money coming into U.S. elections."

He has frequently appeared alongside self-anointed "values czar" Bill Bennett, a conservative Republican, to decry -- as he put it in June 1995 -- the "growing level of garbage that's being thrown at their children across a multitude of media, from cop-killing music to blood-spewing video games to sleaze-ridden talk shows ... a sense that our entertainment producers reject rather than reflect the values shared by most families in this country."

And, of course, on Sept. 3, 1998, Lieberman took to the Senate floor to be the first Democrat to morally "fix" his tom-cattin' pal, the president of the United States -- who had once worked for Lieberman's state Senate campaign back in 1970 when Clinton was a Yale law student.

"A president's private life is public," Lieberman said. "Surely this president was given fair notice of that by the amount of time the news media has dedicated to investigating his personal life during the 1992 campaign and in the years since ... (W)hen his personal conduct is embarrassing, it is sadly so not just for him and his family, it is embarrassing for all of us as Americans.

"The President is a role model who, because of his prominence and the moral authority that emanates from his office, sets standards of behavior for the people he serves. His duty ... is nothing less than the stewardship of our values ... (N)o matter how much the president or others may wish to compartmentalize the different spheres of his life, the inescapable truth is that the president's private conduct can and often does have profound public consequences."

With that opener, Lieberman got to work. Clinton "had extramarital relations with an employee half his age and did so in the workplace in the vicinity of the Oval Office. Such behavior is not just inappropriate. It is immoral and it is harmful." His lying about it was "intentional and premeditated ... Let us as a nation honestly confront the damage that the president's actions over the last seven months have caused," he said, calling for the Senate to "work together to resolve this serious challenge to our democracy."

After his remarks, Lieberman was heralded by his friends across the aisle. Indiana Republican Sen. Dan Coats said Lieberman was "the perfect person, and perhaps the only person in the U.S. Congress, who could do that with the moral authority he has established." A few years before, Coats and Lieberman bonded on a flight back from the Middle East around the time of the Persian Gulf War when both men reached into their carry-on luggage and simultaneously pulled out Bibles -- one Jewish, the other Protestant.

"That speech is considered to be the seminal moment in his life, but for me it's who he is," says Shays. "On the other hand, it's less surprising to me that Joe spoke out against the president's totally unacceptable behavior, and more surprising that other Democrats didn't."

Adds the Weekly Standard's William Kristol, lauding Lieberman's moderation and morality: "He's a man of stature. We have a situation now where the vice-presidential nominees are more impressive than the presidential nominees of their respective tickets."

And at least some of these rave reviews are due to Lieberman's smarts, not just his moral timbre. Shays acknowledges that Lieberman, while a "centrist Democrat," more often than not "votes the party line." It's his public positions -- rhetorical usually more than anything else -- that warm the cockles of so many Republicans' hearts.

"He's a very savvy politician" says the Democratic Senate staffer. "He knows which way the winds are blowing." True believers like Kennedy, or Sen. Jesse Helms, R-N.C., and Don Nickles, R-Okla., on the other side, "are not afraid to sail into the wind. Joe's not that kind of guy. He's very careful about the positions he takes. He's very careful about his public profile."

In October 1991, for instance, Lieberman -- up until the very end -- said he wasn't sure how he would vote on the confirmation of Supreme Court nominee Clarence Thomas.

"All the senators were summoned to the Senate chamber to be seated in their chairs while the roll call was taken," says the Democratic staffer. "But Joe didn't come to [the] floor. He went missing. He later said that he didn't realize the vote was going on. But most people think he was waiting it out to see where votes would be before he cast his own vote."

In the end, Thomas was confirmed, 52-48, with Lieberman voting against his confirmation.

He wasn't always such a centrist. Nor such a media maven. In the Connecticut state Senate, in fact, Lieberman was seen not only as very liberal, but as, according to one profile, a "behind-the-scenes nuts-and-bolts legislator" who worked his way up to state Senate majority leader.

"When he was in the state Senate he was a very liberal Democrat," says Shays, who was in the state House during some of that time. "But you have to remember, when he was first elected he represented New Haven, arguably the most liberal part of the state. It's where Yale is, after all." Which is why Lieberman was there to begin with, having attended as both an undergraduate and a law student. In 1970, at the age of 27, he won a state Senate seat. Four years later he became majority leader.

After 10 years in the state Senate, in 1980, Lieberman ran for the U.S. House seat of retiring 11-term Democratic Rep. Robert N. Giaimo of Connecticut. Before the primary, Giaimo -- who had feuded with Lieberman -- had gone so far as to warn the party not to nominate an "ultra-liberal" -- which many observers took to be a shot at Lieberman. He had, after all, voted to increase taxes as well as to reduce some penalties for criminals.

Calling Lieberman "an outspoken liberal," the National Journal quoted his Republican opponent saying, "I think my stated views on the budget and economics are closer to Rep. Giaimo's than are Lieberman's." Lieberman lost the election.

"His ideology has since gotten more to the center," Shays says. "You could probably say that about a lot of us" former state representatives.

During this time, Lieberman's 16-year first marriage -- which began while he was in law school -- came apart. He and the mother of his three children soon divorced, by all accounts amicably. Beset soon after with names and numbers of eligible nice Jewish girls, he put them in a drawer until he decided he was ready.

In 1982, Lieberman began a campaign for state attorney general. He also decided he was ready to start dating again. On Easter Sunday, he called one of the women on the scraps of paper, Hadassah Tucker, an executive at Pfizer Corp. and the child of a Holocaust survivor born in Czechoslovakia. According to an interview with the Washington Jewish Week, Lieberman decided to call her because he thought it would be fascinating to date someone named Hadassah -- also the name of the Women's Zionist Organization of America. The two soon married and eventually had a daughter.

In November, Lieberman became attorney general. Here is when his media savvy came more into play. In the state Senate, Shays explains, Lieberman "didn't have to work in the limelight -- he already got attention as majority leader. But as attorney general he was competing with the governor and others. And the bottom line to Joe is, he knows the press is the way he can get things done. When he was attorney general, he used the press to highlight things he thought were important. It's not unlike what he's done in the Senate. He's very effective at being on the cutting edge on a lot of issues."

A New York Times profile from his attorney general days called him "grandstanding" and noted his "high-profile reputation -- showboating, some of his critics consider it." His accomplishments included investigating environmental misdeeds, joining -- rather late, some noted -- an antitrust suit against insurance companies, and winning a different antitrust suit against three supermarket chains, after which consumers were awarded $21 million in coupons.

In 1988, Lieberman was contacted by his old buddy from Yale, Massachusetts Sen. John Kerry, then chair of the Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee (and also, conventional wisdom has it, Gore's second choice for veep after Lieberman). Kerry convinced Lieberman to set his sights on the Senate seat of Lowell P. Weicker Jr., a three-term liberal Republican in the U.S. Senate.

He threw his hat into the ring and trailed badly in the polls until he started running an ad created by Carter Eskew, now a key Gore adviser, depicting Weicker as a big sleeping cartoon bear, "'Zzzzzs" floating from a cartoon cave.

"Lowell Weicker is like a big bear," said the narrator. "On things that matter to him personally, he will always growl, but sometimes when it matters, he is sleeping ... Could it make a difference if Joe Lieberman was fighting for us in the Senate? Do bears sleep in the woods?"

It was jocular negativity -- an area where Bush has proven to be quite adept and Gore ham-handed.

"I don't know what Mr. Lieberman is, and I don't think anyone else does either," Weicker said of his opponent's political views. "He dashes here and there just so he can be in opposition to Lowell Weicker ... This man is zigzagging all over the place. Whoever his supporters are they must be scratching their heads."

They might still be scratching. Lieberman squeaked out a victory in 1988 by about 10,000 votes, and has since been reelected by a margin approximately 35 times that. (Only token opposition faces him this November, where -- as is permitted in some states -- Lieberman can run simultaneously for reelection as senator and election as vice president.)

In his 12 years in the Senate, as the RNC's Nicholson correctly pointed out, Lieberman has voted against the wishes of his leaders on a number of high-profile issues, though in general his votes are reliably Democratic, leaning liberal.

Democratic staffers might grouse at Lieberman's expertise at negotiating the terrain between serious and media-lusting, between partisan and independent, but they would do better to take notes. An early supporter of Bill Clinton in 1992, Lieberman was the subject of a pictorial essay in the Washington Post for his impeachment vote. Here's Joe Lieberman agonizing! Here's Joe Lieberman being serious and consequential! Here's Joe Lieberman voting against impeachment, just as we always knew he would!

Not that there aren't times that Lieberman proves himself to be a legitimate "New Democrat": Lott spokesman Czwartacki credits Lieberman with rallying Democrats in March 1996 to help provide a veto-proof majority for a small "tort reform" measure that would limit damage awards in product-liability cases that Clinton threatened to veto in 1996.

Additionally, there are moments that Lieberman's bipartisanship and genial gallantry lead him to shun the spotlight. When the Senate finally passed a bill this past spring requiring the disclosure of the individuals funding ads for "527" political groups, it was Sen. John McCain, R-Ariz., who got the credit, even though the bill -- the first serious achievement in campaign finance reform in eons -- had been Lieberman's idea.

It will be interesting to see how Gore's selection of a moderate floats with liberal special interest groups. In this last congressional session, for instance, Lieberman voted for a bill offered by Sen. Orrin Hatch, R-Utah, to use Title I money on a school voucher program. It's also probably worth noting that Lieberman's votes on experimental school voucher programs are similar to programs Gore slammed Bill Bradley for supporting during the primaries.

"We do know that he's had a number of votes in support of school vouchers," says Darryl Figueroa, a senior professional associate at the National Education Association, a teacher's union. "But we're sure that won't have any effect on the position that the ticket has. With Vice President Gore in the leadership position on the ticket, there's no way that he'll do an about-face on that issue."

But Lieberman's occasional flights from Democratic orthodoxy are clearly a touchy subject. Liberal interest groups whose spokespeople are usually quite garrulous -- the Association for Trial Lawyers of America, the National Abortion and Reproductive Rights Action League and Americans for Democratic Action, for example -- did not return calls for comment on Lieberman's selection to the Democratic ticket.

And interestingly, in stark contrast with the way the Democratic establishment trotted out the most Cro-Magnon parts of former Rep. Dick Cheney's voting record, Gore's GOP opponents have already begun praising Lieberman as a centrist -- and slamming Gore for picking him for that exact reason.

"Governor Bush thinks Joe Lieberman is a fine man, a good man, a man of integrity, and an intellect," says Bush spokesman Ari Fleischer. Lieberman's tenor and tone are precisely what Bush means when he talks about "changing the tenor and tone in Washington," Fleischer says. "We hope Joe Lieberman will lift Al Gore up, not that Al Gore will bring Joe Lieberman down."

That said, Fleischer adds, the policy differences between Gore and his running mate raise at least one question: "Given the vociferousness of all Al Gore's attacks, and the fact that Sen. Lieberman's positions are similar to Bush's -- which Gore has attacked -- it raises the question as to whether Al Gore really believes in the things he's saying or is he just a politician who will say anything to get elected?"

After all, mavericks like Lieberman can provide both cover and ammunition. At a September 1988 debate at the Stamford Italian Center, Lieberman -- gunning for Weicker -- slammed the incumbent senator for his independent ways.

"For 18 years, my opponent has gotten away with saying he's a maverick," Lieberman said. "Well, it's about time the people really understood what a maverick is. It means you're not ultimately accountable to anybody. You don't even have to make commitments, even to the voters you represent. You just do whatever suits you personally whenever you want to do it. I look at his record and see a pattern of incredible inconsistency."

No doubt today Lieberman would have a different definition for the term. As would Al Gore.

Shares