Kate Mantilini's is an overpriced, smug little diner on Wilshire Boulevard in Beverly Hills known chiefly for selling heaping plates of frog's legs to the Armani and Prada set. Were it not in Beverly Hills, it's unlikely it would get away with serving anemic burgers and tasteless fries with patronizing sniffs from its wait staff. But it does get bragging rights for famous faces. Like on the night of June 22 when it seemed the entire cast of Robert Altman's "Nashville," along with Altman himself, had retired from their 25th anniversary party at the Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences to the only nearby spot open past 11 p.m.

As luck would have it, I was on hand trying to find the meat in my bun when the first onslaught of "Nashville"-ites arrived, buzzing about the place, waiting for their leader. There was Henry Gibson, accompanied by his wife; Ronee Blakley, with her daughter; Michael Murphy, looking as handsome and buttoned-down as, well, Michael Murphy; and the aptly named Karen Black stalking about with the intensity of a mental ward escapee on the hunt for the sharpest piece of cutlery in the joint.

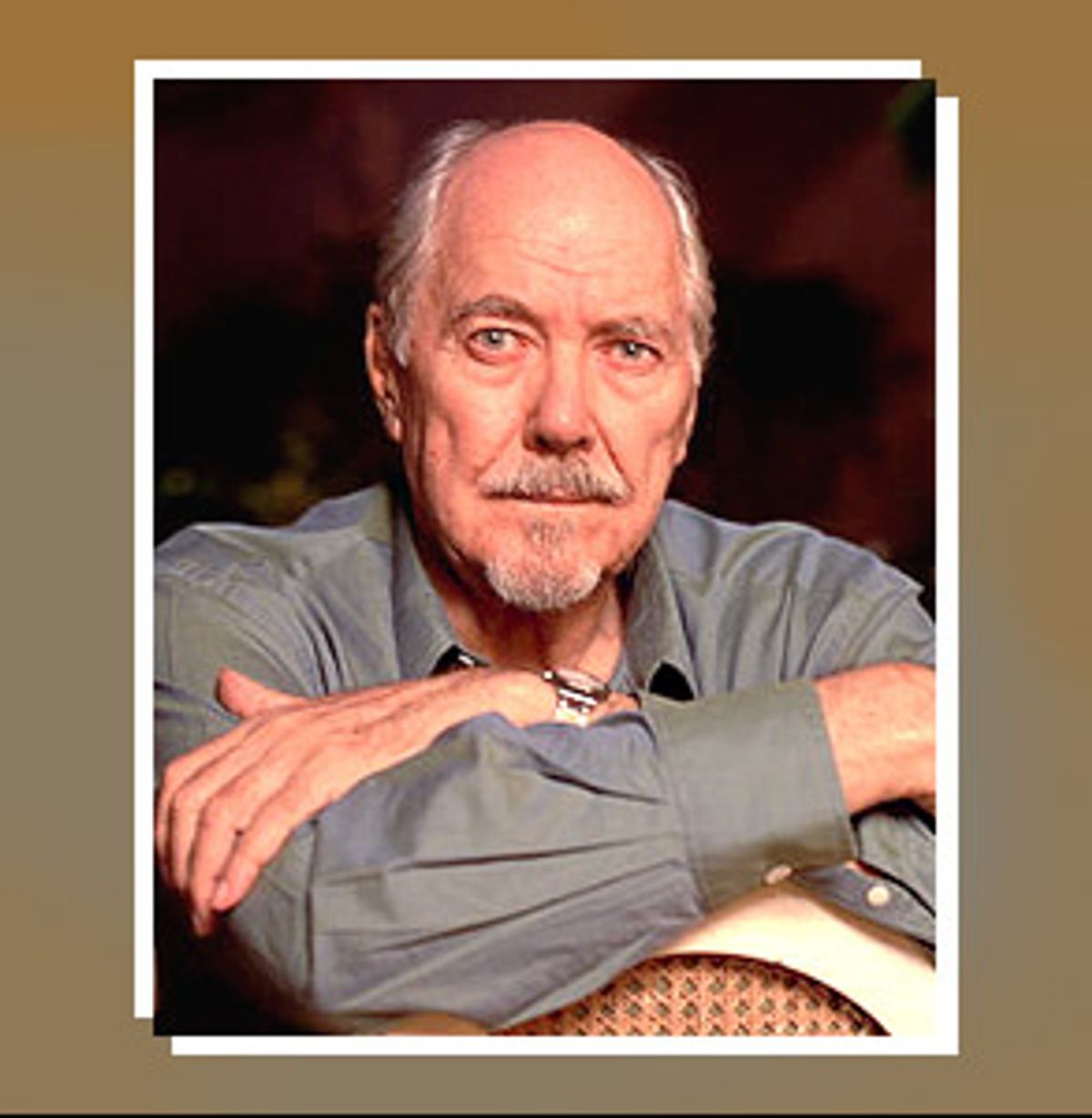

Altman finally arrived in a group. Dressed in rumpled white pants, a black jacket and a white shirt open at the collar, the 75-year-old director was one part Foghorn Leghorn, one part Big Daddy from "The Long Hot Summer" and one part Nutty Professor (pre-Eddie Murphy), the last bit emphasized by his white sneakers and a pair of black- and blue-striped socks.

The waitresses pushed two tables together, and Altman and his entourage were seated. There were constant migrations to Altman's table, where he sat nibbling on some bread in his long, delicate hands, wearing a grin he might've stolen from some old print of a Pasha in his harem.

In a way, Altman was in his harem -- his harem of actors and actresses. It was an incestuous, chaotic scene that could have been lifted from one of his films -- "A Wedding," "Nashville" or "MASH" -- with each character, such as Murphy or Blakley, jostling the other to come closer to their adopted father. And just like all of those grand, layered ensemble masterpieces for which Altman is renowned, it was Altman himself who was at the center holding it all together, basking in the love of his wayward children.

Now before screaming "muddled metaphor" -- crossing a harem with an extended, flaky family -- consider the high praise actors award him, such as these remarks, culled from the post-"Nashville" screening discussion that took place just before the soiree at Kate Mantilini's.

From Robert DoQui, who plays Wade, the black dishwasher pining for Gwen Welles' Sueleen Gay: "One of the most remarkable experiences is to work with a director who allows trust on the set and among the actors. A lot of the improvisation and a lot of the work comes from that trust ... In order to find new creative moments, you have to have the freedom to explore and fall on your face. Robert Altman allows it, and I love him for it ..."

From Blakley, whose mental meltdown as the snow-pure Barbara Jean is at the crux of "Nashville," describing how Altman allowed her to write the monologue of her psychic collapse before a country music audience: "I remember having this black, covered journal I had scribbled away in. I was in makeup that morning, and I asked if I could speak with Bob. He came down to speak with me, and I showed him what I had written. He asked, 'Do you know it?' and I said, 'Yes.' And then he said, 'Let's shoot it.' But as I had written one speech, Bob is the one, of course, who said, 'Let's break it up a couple of times.' That's why Barbara Jean stopped and started again twice. It was very exciting. An extreme high, creatively."

From Henry Gibson, who played corn-pone country music legend Haven Hamilton and got the big laugh of the evening with this: "I remember one lovely line that Bert Remsen (one of Nashville's bit players) said to me in the middle of all this great madness. He said, 'You know, Henry, being in a Robert Altman film is like sex. When it's good, it's very good. And when it's not so good -- it's still good."

And finally, from Altman stalwart Murphy, who plays politico John Triplette in "Nashville" and who has brought to life key roles in "Kansas City," "MASH," "McCabe and Mrs. Miller," "Tanner '88" and numerous other Altman projects: "Thanks for my life, Bob!"

The feeling Altman's actors have for him is a mix of what one might feel for a father and a lover. Granted, this feeling sometimes tends to develop more in hindsight. (Folks forget there was a bit of rebellion on the set of "Nashville" when Barbara Harris demanded some back pay due to all.) Altman has butted heads with many of his stronger-willed actors, like Elliott Gould and Donald Sutherland on the set of "MASH" or Warren Beatty on the set of "McCabe." Like any great American father figure, from FDR to Billy Graham, Altman is a dictator, albeit one with a gentle hand. It's his way or the highway.

Altman as the paterfamilias of a dysfunctional family that he has assembled is often alluded to, indirectly by Altman in interviews, and more directly by those who take the irresistible bait and write about him. When he explained to a group of radio journalists in 1999 how he selects a cast, the process sounded like someone putting together a temporary family. "It's getting these actors who are in harmony with each other," said Altman. "I never cast a picture the way the studios do. They'll take two people who just hate each other, and pay them enough money to get them in. They show up to work and never know the other actors. I don't have that kind of money. So the ones I work with, they all want to do it. That's why they became actors in the first place -- to create. And I make 'em. I say, 'Create. Show me what you can do.'"

Like kids trying to please their papa, the actors and everyone else involved in an Altman film, it seems, scramble to prove themselves. Surely this is why Altman has masterminded so many textbook examples of fine ensemble acting.

For Altman's only biographer, Patrick McGilligan, it's one of the primary themes of the director's life and work, which he hammers home in his monumental 652-page book "Robert Altman, Jumping off the Cliff." In the book, McGilligan meticulously documents the "family atmosphere" on Altman's sets -- the "nightly movies," the "requisite dailies" the whole cast would watch and critique, the "communal popcorn, drinking and dope smoking" and the "parties and entertainments." It's all part of an elaborate "courtship ritual" designed by Altman to seduce his charges.

If one's to judge by comments from actors, collaborators, Altman himself and the countless others who've written articles about the man, McGilligan is right on the money. And though his Altman wears no halos in the book (the author variously describes the director as a womanizer, a boozer and an impatient, prickly egoist), it's McGilligan's intention to enshrine Altman as one of the greatest directors of our time -- perhaps the greatest living American director, with the exception of Woody Allen. In McGilligan's account of Altman's risk-filled life, the filmmaker comes off like a latter-day Zeus, with all the foibles of the original Olympian and a few of the powers -- such as the ability to fling thunderbolts.

"That's such shit," Altman said of McGilligan's book when I spoke with him in the summer of '99. "Oh, that is so apocryphal, I can't even tell you. That guy [McGilligan], I just think he got drunk and did it. He ended up talking to a bunch of aunts of mine."

Then, he leaned back in his chair and unleashed full spleen on McGilligan, whose unauthorized biography had led me to admire Altman even more than I had previously. Why did he dislike the biography so?

"He's got me in Paris, at one time walking down the street -- following Orson Welles who was my 'hero,'" he explained. "Not even close. I'm not even a big fan of Orson Welles. I think he's got his place. 'Citizen Kane' was OK, but I wouldn't put it down as one of the great films of all time. And here's this whole thing that's just wrong. I wouldn't be ashamed of it if it were true. It's just wrong."

The episode Altman alluded to is a very small piece of the whole -- it takes up about a paragraph, even though there are longer spiels where McGilligan quotes friends of the director who vouch for his early hero worship of Welles. It seems such a small point, but evidently it was enough to royally piss off Altman. In fact, he spewed a bit more about McGilligan before I got up the nerve to suggest that a memoir from him might set the record straight.

"I don't know," he sighed. "If I can't work for some reason and my brain's still alive, I might do something like that. But I don't know how interesting it would be. It's been a pretty even existence for me. Besides, I'm not sure my version would be the correct version either."

- - - - - - - - - - - -

Robert Altman was born in Kansas City, Mo., on Feb. 20, 1925, a Pisces near the tail end of Aquarius -- a party sign if there ever was one. Conditions were right to back up the verdict of the stars. Altman's father, B.C., an ace insurance salesman for Kansas City Life, could sell a policy to a corpse, and may have once or twice. By turns an inveterate gambler, family man, regular Catholic, whiskey-drinker and skirt-chaser, B.C. sounds something like his son -- except for that regular Catholic business.

Altman's mother, Helen, was devoted to her son and his two younger sisters, Joan and Barbara. A convert to Catholicism, she was more refined and arty than her husband, and she had a passion for social functions. As B.C. was usually off selling insurance or playing poker, Altman grew up in a house full of women -- sisters, aunts, his mother and her friends.

The Altmans were decidedly upper-middle class. Of German-American stock, they were one of the leading families of Kansas City. Altman grew up privileged and a little spoiled. After all, he was the only boy and the eldest child.

When he spoke to me about "Cookie's Fortune" last year, he was full of fondness for that middle-American lifestyle he knows so well. "I was very comfortable in that town," he said, referring to Holly Springs, Miss., where "Cookie's Fortune" was filmed. "I had a lot of dij` vu shooting and living there. Those houses -- those craftsman houses they built in the '20s. I lived in one that was really very familiar -- similar to the kinds of houses that were in Kansas City when I grew up. We'd sit on the front porch in swings, the kids would run up and down the street and catch fireflies and put them in bottles. It was very neighborhoody." Hence the recurring Altman motifs: the large extended family, the generally prosperous Americana, the roguish behavior of the males and so on.

As an adolescent Altman was a cutup and hell-raiser -- to the degree that his parents shipped him off to Wentworth Military Academy in Lexington, Mo., during his junior year of high school. In 1945, he left the academy for the Army Air Force and what remained of World War II.

After training at a base camp in Southern California, Altman shipped out for the island of Morotai in the Dutch East Indies. There he spent the waning days of the war copiloting a B-24 and dropping payloads on Japanese positions. When he wasn't doing that, he was playing poker with his fellow officers or bird-dogging nurses. Also, according to Altman, it's when he began to consider a career in the movies: "The first time I ever thought about film was when I was overseas in the Second World War," he told me. "I started writing radio plays. I was very interested in that. And then I started to write screenplays -- not screenplays so much as stories to make movies from. Since then, it's just been down the same road."

After the war, he headed to Los Angeles and dove into a number of schemes. He tried being an actor briefly, and he even appeared as an extra in the 1947 Danny Kaye classic "The Secret Life of Walter Mitty." You can see him grinning past Kaye in a bar scene if you don't blink. But acting didn't work out, and he then got involved in a bizarre business venture -- a national identification system for dogs in which license information would be tattooed inside the canine's right front leg. Altman and his partners even went to the White House and tattooed President Harry Truman's dog before the business went bust. Soon enough, Altman was back in Kansas City, broke and hungry for action.

In those days, there were no film schools, but at the age of 22, Altman hit on the next best thing. He joined Kansas City's Calvin Company, which was then one of the leading makers of industrial short films in America. Altman went on to make 60 films for the company on every subject imaginable -- from football to car crashes. But he kept grasping for more challenging projects. In 1955, he wrote and directed a low-budget teen exploitation movie titled "The Delinquents." That year, he left Kansas City for the last time, ostensibly to edit "The Delinquents" in Los Angeles.

Released in 1957, "The Delinquents" was hardly a runaway success, but it did catch the eye of Alfred Hitchcock who tapped Altman to direct a few episodes of "Alfred Hitchcock Presents." Though Altman fell out with Hitchcock pretty quickly, he was on his way as a successful TV director, and went on to work on series such as "Bonanza," "The Millionaire," "Bus Stop," "Route 66," "The Troubleshooters" and "The Whirlybirds," on the set of which he met his third wife, Kathryn Reed; they've been married since April Fools' Day 1959. (Altman has six grown children: Michael, Stephen and Christine from his previous marriages; Matthew [adopted]; Robert, his son with Reed; and Konni, Reed's daughter. He has 11 grandchildren and four great-grandchildren.)

Perhaps his most important TV work was in the early 1960s for the show "Combat" with Vic Morrow, the late father of Jennifer Jason Leigh. The gritty war drama followed a U.S. Army platoon in France after the invasion of Normandy, and it's still considered an influential series by critics and filmmakers. Unlike the hack work he did for the Calvin Company, Altman doesn't disown "Combat," but seems to regard it with pride.

"The Museum of Television and Radio [in Beverly Hills] has most of it," he told me in an interview just before the "Nashville" screening at AMPAS. "I was in Austin [Texas] last September and October for the Austin film festival. They showed 'Nashville.' They also showed two or three [episodes of] 'Combat' I had written and directed. I hadn't seen those for 40 years, and I thought they held up pretty good ... My god, I've done hundreds of hours of television, and I've done about 38 films. I don't think anyone thinks about that at all. They don't add up all those points until you're dead. Then you can't fool 'em and make any more."

After leaving TV and with a few years of fumbling, Altman scored a job directing his first big studio feature -- 1968's forgettable space-race flick "Countdown" starring James Caan and Robert Duvall as rival astronauts. It was a flop, but a step in the right direction. His next project was the far more accomplished psychological thriller "That Cold Day in the Park" (1969), starring Sandy Dennis as a sexually stifled spinster on the verge of a homicidal nervous breakdown. Shot in Vancouver, B.C., it's a gelid, brilliant piece of moviemaking akin to Roman Polanski's early films "Repulsion" and "Knife in the Water."

But Altman was to make his name, if not a lot of money, with his next project -- the phenomenally successful Korean War romp "MASH" (1970). The Ring Lardner Jr. screenplay had been making the rounds for some time, and 15 directors -- including Stanley Kubrick and Sidney Lumet -- had passed on the adaptation of the novel by 'Richard Hooker' (a pseudonym for authors H. Richard Hornberger and William Heinz) by the time Altman got his hands on it and saw his chance. For a flat fee of $75,000 with no percentage of the gross, he signed on to the 20th Century Fox project.

"MASH" introduced audiences, in the most accessible way possible, to the Altman style -- ensemble acting, episodic storytelling, zoom lenses and overlapping dialogue. It also fed them all of the major characteristics of an Altman film: rabid anti-authoritarianism, anti-militarism, black humor (the blackest), sacrilege, delight in decadence, adolescent sexual escapades, hypocrisy revealed and casual drug use.

The movie made stars out of its two leads, Elliott Gould and Donald Sutherland; started a running story line the TV series "M*A*S*H" would milk for years; and put a giant bulge in Fox's corporate wallet. "MASH" cost a measly $3.5 million to make, but according to Peter Biskind's account of the late '60s and '70s in Hollywood, "Easy Riders, Raging Bulls: How the Sex-Drugs-and-Rock 'n' Roll Generation Saved Hollywood," the film "pulled in $36.7 million ... putting it third for 1970 behind 'Love Story' and 'Airport.'" And that's not counting the loads of cash made from the TV series.

Altman, of course, didn't see any of that money. And he would often complain that his son Michael, who at the age of 14 wrote the film's popular theme song, "Suicide is Painless," made more than he did off of "MASH." But Altman got what he really hungered for: acclaim as an artist. The film struck a chord both with the youth culture and the burgeoning anti-Vietnam War sentiment in the United States and abroad. At Cannes, "MASH" was awarded the Palm d'Or for best film. And it received five Academy Award nominations, including best picture and best director, though it won only one: best screenplay -- for which Lardner got the Oscar.

It's hard to overstate the importance of "MASH" to Altman's career. At 45, he was older than the Young Turks then kicking new life into old Hollywood. But overnight he became leader of the pack, universally hailed as a genius, an auteur, a demon filmmaker and an iconoclast. He took the brass ring and ran with it -- sometimes making bizarre but fascinating failures like "Brewster McCloud" (1970), "California Split" (1974) or "Buffalo Bill and the Indians" (1976), and with other projects crafting literature on-screen in films such as "McCabe and Mrs. Miller" (1971), "The Long Goodbye" (1973), "Nashville" (1975) and "Three Women" (1977). Even his over-the-top 1978 farce "A Wedding" and 1979's often reviled sci-fi thriller "Quintet," though flawed in their own ways, reveal the idiosyncratic brilliance of their creator.

The '70s were very good for Altman, as they were for film in general. Biskind quotes the director as saying of the era: "Suddenly there was a moment when it seemed as if the pictures you wanted to make, they wanted to make." But if art and commerce held hands like hippie lovers during the '70s, the '80s would see them part, with commerce going back to its old whorish ways.

That was when Altman, in the oddest move of his career, directed "Popeye" (1980) with Robin Williams. The result was a creative nadir. The film was a failure at the box office, though it eventually ended up making big bucks in rentals. And whatever its merits for the kiddies, it signaled the end of a victorious, decade-long run for Altman -- put Williams as Popeye beside Beatty as McCabe: It illustrates a sort of spiritual regression, a de-evolution worthy of Mark Mothersbaugh.

He followed the "Popeye" defeat with a series of less-ambitious but still aesthetically satisfying film adaptations of stage plays, "Come Back to the Five and Dime, Jimmy Dean, Jimmy Dean" (1982) and "Secret Honor" (1984) being the best of these. During the '80s, there was also the raucous "Les Boreades" segment from the opera anthology film "Aria" (1987). But his "Vincent and Theo" (1990), shot originally as a four-hour epic for European TV, was Altman's first true masterpiece in over a decade. A long, mordant commentary on the fate of an artist in society, "Vincent and Theo" proved that Altman, seemingly at will, could invest celluloid with the grandeur and depth of high art.

But Americans want entertainment, and Altman made clear with 1992's "The Player" and "Short Cuts" (1993) that he can deliver it, though not without a satirical price. When Tim Robbins' movie mogul in "The Player" gets away with murder, the audience ends up cheering him. And if "Short Cuts" is filled with crude vignettes, like Huey Lewis peeing on a floating female corpse, we still laugh at it, albeit with a little embarrassment. It's almost as if in both films, Altman is saying in no uncertain terms, "I know what you folks are really like, so let me hold up a mirror and you can tell me if you enjoy what you see." It works. We guffaw at ourselves. And if there's a tinge of self-revelation as we gaze inside Altman's funhouse mirror, we can always shake it off afterward. It's only a movie, right?

"Ready-to-Wear" (1994) didn't click with audiences in that "Short Cuts" way. And "Kansas City" (1996) was more like the old Altman -- a dark, cynical jazz-inspired portrait of his hometown in the 1930s. Yet it's a breathtaking film, with fantastic performances from Jennifer Jason Leigh, Miranda Richardson and Harry Belafonte.

Since then there's been 1998's "The Gingerbread Man," based on a John Grisham short story, which, for the most part, has been consigned to oblivion. But if Altman couldn't make gold out of Grisham's dross, who can blame him? Most recently, in 1999, there was "Cookie's Fortune," a gentle farce of a Southern mystery that almost everyone seemed to love -- even though it disappoints Altman that most people waited to see it on videotape.

"People can't get out," he said in 1999. "They say, 'Oh, we've got to get babysitters.' They can't do it the week the film is open, and that's about how long they last. There are so many of them vying for people's attention. Most folks end up seeing it on the tube." Altman knows times have changed. It isn't the '70s anymore, where adults make an effort to go to the movies once a week. And that's the reality you have to deal with. "The exhibitors, they don't give a shit whether it's 'Stormtrooper's Delight,'" he said. "If it sells tickets and popcorn, that's what they're after. So we just have to throw it out there and hope it finds an audience before it gets out of the theaters."

Movies are a popular medium, and elitism can only get you so far. Altman does better than most at fusing his own peculiar vision with the dictates of the American marketplace. After all, he was able to snag Richard Gere to play the lead in the upcoming "Dr. T. and the Women," a thought that may make some folks cringe but is certain to make many more laugh. Following up on the success of "Cookie's Fortune," Altman's all but rubbing his hands as he readies for the release date, putting finishing touches on the film. "Richard Gere is just so good in this picture," he said to me recently. "There's not a false move in it. 'Dr. T' is as good as I can do. If someone doesn't like 'Dr. T,' all I can say is that I can't do any better. Everything came together on this picture. It just all worked."

Altman could easily pass for 10 years younger than his 75 years, and he's so sharp mentally he could verbally tear to shreds anyone he so desired torn. Good Lord, the man may have another 20 or so years of films left in him if we're lucky.

His stature is such that at this point, we might as well declare him a national treasure and get it over with. Young filmmakers, notably "Magnolia" and "Boogie Nights" director Paul Thomas Anderson, worship him. And the 25th anniversary of "Nashville" left writers tying themselves into knots, lauding him. Whether or not his next film is a critical or commercial success, the ultimate outsider is at long last the Big Daddy of American cinema. Is there any other active director, since the death of John Huston, who could lay claim to that title? (And please, don't mention Steven Spielberg. I'm not talking about sausage makers.)

Altman himself is modest when asked about the aesthetic level he's achieved compared to, say, his TV days. "I don't think your art changes," he told me. "You get a little more facile. You learn more technically and become a little more efficient. You learn all that stuff. But your art doesn't get any better. You just get a little more clever. A little more commercial, really."

He may be more commercial, in some ways, than in his heyday in the '70s. But I'll be damned if, barring Martin Scorsese or Sidney Lumet, there's another director who even comes close to approximating his artistic output -- flops and all.

Shares