Vincent D'Onofrio doesn't look like a movie star. Slightly disheveled, in a long-sleeved black shirt with the tail hanging out over gray pants, he looks more like some suburban dad who just rolled out of bed on a Sunday morning to fetch the paper in his socks. (In fact, he's married and has two young children.) With his dull brown eyes, closely cropped gray-brown hair and Vandyke beard, D'Onofrio could be any guy in a crowd. There's not an iota of glamour in his stooped, out-of-shape 6-foot-3 frame.

But D'Onofrio is a movie star, though not as a result of good looks or sex appeal. Rather, the 41-year-old, Brooklyn, N.Y.-born actor has talent on his side. That, and a gift for selecting plum roles. His film career began when his pal Matthew Modine hooked him up with Stanley Kubrick for a part in "Full Metal Jacket." You may recall D'Onofrio as the hapless Gomer Pyle, the inadequate Marine recruit who ends up killing his sergeant and himself. There were also bit parts in major films like "JFK," "Malcolm X" and "The Player," but it was his leading role as novelist Robert E. Howard, creator of "Conan the Barbarian" and "Red Sonja," in "The Whole Wide World" that put him on the map.

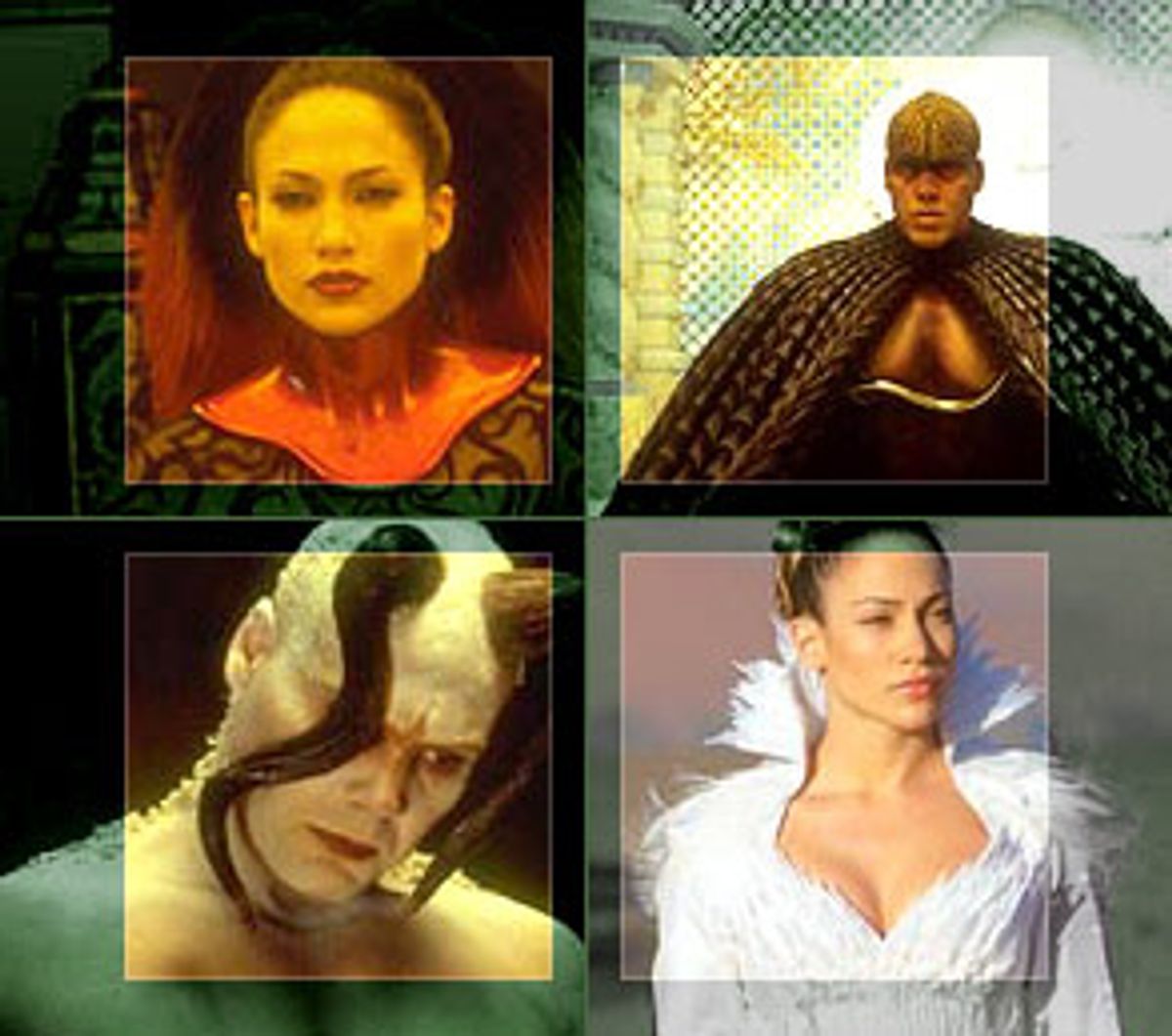

Now D'Onofrio's in the catbird seat with starring roles in two new films that open Friday: "The Cell," a brilliant horror/sci-fi flick in which D'Onofrio plays a serial killer whose cerebral cortex becomes the war zone wherein he and Jennifer Lopez do battle; and "Steal This Movie," a disappointing examination of yippie leader Abbie Hoffman's life. D'Onofrio portrays Hoffman in the latter, his performance rescuing the film from its TV movie format. But D'Onofrio's performance in "The Cell" really blew me away, and that's mainly what we talked about during an interview earlier this week in Los Angeles.

What was it like playing a serial killer in "The Cell"?

It was tough. It was something I was reluctant to do because there have been performances about serial killers in the past that have done pretty well. I figured society pretty much knows enough about serial killers by now. But then I met the director, Tarsem Singh, and his vision won me over. Basically everything in that film is because of him. The actors did their work and brought things to it. But in the end that film is the way it is because of Tarsem.

I thought it was a good chance to take. I've taken chances before in my career, so I figured I'll take this one, what the fuck, you know? I just kept it out of my mind that you'll never be able to top an Anthony Hopkins performance, so don't worry about it. It's like playing someone who's mentally impaired now ever since Billy Bob Thornton did "Sling Blade." You can't touch a performance like that. It's like "Streetcar" after Brando. It's dead.

Your performance in "The Cell" seems deliberately low-key. Was that part of some plan to make your character, Carl Stargher, sympathetic?

The serial killer was down, but you've got to remember we had allowances, because once you're in his head everything is wide open. So that was Tarsem's and my choice.

About the sympathetic thing, if we had had it our way, there would have been no pity at all. I'm totally against that. I hate the idea of bad guys walking away at the end of movies -- because I have a family and stuff. It just bothers the shit out of me.

But we had to keep on course so we didn't do this entirely different movie. What we had to keep in mind is that we're not trying to redeem him, we're trying to define his psychology. The only chance to do that is showing him when he's a child and revealing his evolution as a human being, what he grew up to be because of certain circumstances.

There's an intense scene in the film where Stargher's suspended over a dead, naked woman by steel rings that are pierced into his skin. Can you describe the filming of that?

It was uncomfortable. A body double shared half the pain with me for all the wide shots. I had to do all the closer stuff. You're harnessed up, and prosthetic skin is glued to your skin. You're hoisted up by cables hooked to a harness beneath this fake skin. I mean, it's not digging ditches or anything, but it's not the first thing you want to do in the morning. Actually, in the photos of people who do that, their skin stretched a lot farther than we stretched it. They wouldn't allow us to stretch the skin any farther.

Was that scene cut?

Yeah, they cut it down so it's really just hinted that he's masturbating, rather than showing it. Not that we show any frontal nudity or anything. But I went through the act where my arm comes around, goes over my penis, working into the orgasm -- all that was in the original scene. And then the orgasm itself, they wouldn't allow it. So Tarsem had to snip, snip, snip and just kind of hint at it.

Why do you think people are fascinated with serial killers?

It's like why people read scary books or go see scary movies. Because it creates a distance. They're scared, but they're not going to get hurt. It's the same reason why people get S/M prostitutes to come over and whip them. They know at the end of the evening they're not going to die. It's just a kink. Some people have it. It leans toward being pathetic, but it's still human.

Yet it is somewhat pathetic because they know they're not going to be murdered. They're going to pay the prostitute; she's going to do her job and spank them or make them run around in a diaper with a snorkel. Then at the end of the evening, they're going to go home, cuddle up to the wife and be nice and safe. It's the same thing.

Is there any similarity between what you've just described and acting, since you get to pretend to be a serial murderer or Abbie Hoffman and then go home?

I wouldn't put it in that area. I'd put it more in the area of expressing your creative side, whatever form that comes in. The strange people I've met in my life so far, the stranger they are, the more unlikely they would be putting themselves in the public eye. The actors, musicians and writers that I've met -- they're a bit odd, but they're odd in a creative sense. They have some need to flex their creativity. That's kind of their kink, my kink, our kink.

What kind of research did you do to prepare for the role of Stargher?

I don't want to get into it too much because some of it's too harsh. But, you know, there's so much access to things these days because of the Internet. I had books and encyclopedias on it, letters from the insane dating back to the 1700s, books of art made by the insane. My room at the Chateau Marmont was full of this creepy stuff I was reading and studying -- pictures and photos and things.

Was that particularly disturbing, going through all of that?

Yeah, but it just gives you nightmares, like it would anybody. I remember going with my wife to bookstores and looking at books of old '50s pinups and kind of sadistic stuff -- things that don't go through my mind, these kind of drunken, slutty, big-breasted women with their breasts falling out of their bras. Images like that which I can't conjure up myself are disturbing. But it's stuff I had to get into my head for this role -- looking at women in a sexual-object kind of way.

One of the great moments in the film is when Stargher and Lopez's character, Catherine Deane, have a conversation while your hands are playing in the bloody water of a bathtub containing a nude, female corpse. Can you describe what was going on between you and Lopez in that scene?

All the times that Jennifer and I were together, it was very quiet, particularly in that scene. Her approach to it was very silent and my approach to it was very silent. Nobody knew what I was going to say. They certainly knew by then that I wasn't going to stick to the script. Jennifer and I never spoke about any of the scenes we were going to do on purpose. It got to the point where if anybody had interrupted what we were doing, the whole mood would have crashed down like glass. It was that fragile -- quite an intense day.

The girl who was in the tub, she had to lie there -- not very nice. I didn't know her name -- some model chick. She certainly wasn't going to talk to me. And I wasn't going to talk to her. It was that mood on the set. The cool thing about doing a film like that, unlike the "Steal This Movie" part, is you don't have to be social at all. I prefer that. That's more my personality. I can carry that feeling around with me when I'm doing a part like that where I don't want anyone to know what I'm going to do. That is, if the director allows that.

So I riffed on the idea of what was there and did many different versions of it. Then when the camera was on Jennifer, I did something completely different to bring some tears up in her. Something I won't discuss with you. I said things that I knew would move her. But that's not uncommon; actors do that all the time.

How do you know what to say to get that kind of reaction?

We're actors. We know that shit. If we don't know anything, we know that.

You've done disturbing roles before -- was Stargher the most disturbing?

As far as a fictional character's morals, he would probably be the least moral person I've ever played.

How did you approach the role of Abbie Hoffman in "Steal This Movie"?

I approached it as a drama about this man's emotional life with the background of this revolution going on. I knew a bit about Abbie, but I'm a little too young. I was born in '59. So when I read the script, it read more like a drama to me.

Yes, there were the events that actually happened, and we felt legitimate about the way we portrayed them because we had Anita Hoffman [now deceased, played by Janeane Garofalo in the movie] with us, Tom Hayden and Gerry Lefcourt, his lawyer -- people who were there, confirming things for us.

What's more difficult -- playing a purely fictional character or doing something biographical?

There's a lot of shame that goes on when you're playing someone who has really lived and has passed. You're struggling with it all the time. I am, anyway. When I played Robert Howard in "The Whole Wide World," I was struggling with it. There's this dual thing where you feel real good about being able to play this juicy part, and then there's constant shame. Who am I to pretend to know who this guy was? Who am I to represent this guy for people who never knew him? The pressure is unbelievable, I can't tell you.

Shares