The novella is a strange and stubborn beast. It dwells along literature's brambly edges, somewhere between the shadow-strewn forests of the novel and the tidy, fenced-in pastures of the short story. Little wonder, then, that Jim Harrison should be drawn to the novella form. Harrison has been prowling the literary edges for four decades now, stubbornly eluding the snares of critical reduction -- including such dim taggings as "macho" and "regional" -- while producing a body of work so lushly idiosyncratic as to thwart even the gentlest efforts at classification.

The novella suits Harrison. Not for him the constricted focus and pinprick epiphanies of the short story; even his sentences, with their roundabout subjunctive clauses and hydra-headed coils of thought, cry out against containment. And though he's penned his share of novels, most recently 1998's "The Road Home," Harrison's glibly wounded narrative voices seem better suited to the unbroken intensity that the novella form can provide. Not surprisingly, then, his three previous collections of novellas -- "Legends of the Fall," "The Woman Lit by Fireflies," and "Julip" -- are considered by many to be the brightest stars in Harrison's galaxy of work.

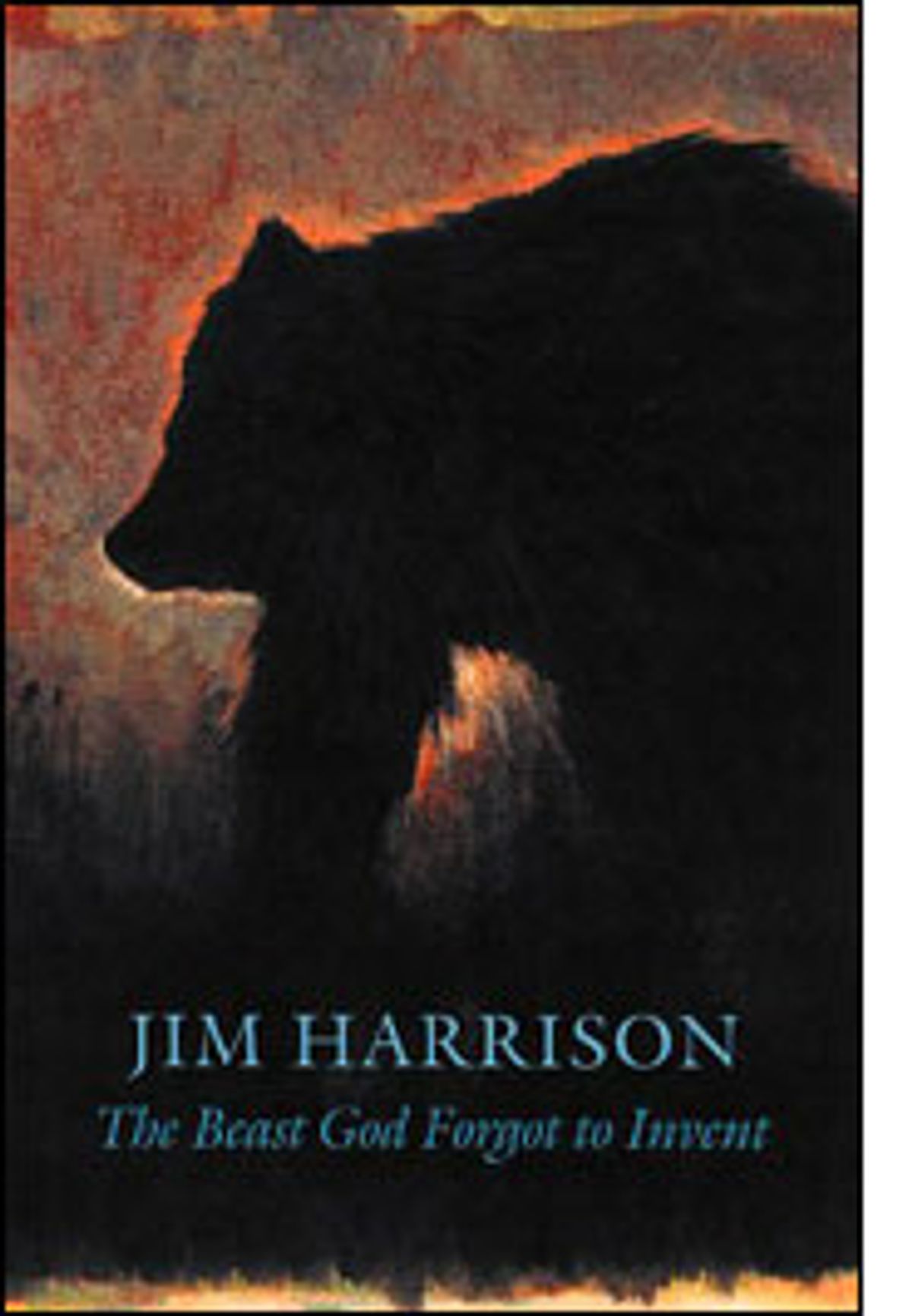

With the publication of "The Beast God Forgot to Invent," those stars gain dazzling new company. The title novella, set in Harrison's native Michigan, takes the guise of a written report to the Alger County coroner -- a report that, like the life (or rather death) it purports to describe, goes beautifully haywire. The narrator, Norman Arnz, a 67-year-old commercial real estate broker and rare-book dealer, is the quintessential Harrison narrator: Overbrimming with prickly opinions and runaway anecdotes, Arnz presents less a narrative of his pal's drowning death than a cranky treatise on the pitfalls of civilization. His pal's drowning followed a motorcycle accident that served to decivilize him. For one, the injuries had turned him weirdly primal, prompting him to flee society for something resembling a cave man's rough-hewn life. For another, he'd lost his capacity for visual memory. (As Arnz explains, "Joe's very least problem was boredom because everything he saw he saw for the first time, over and over.") As a daily explorer in terra incognita, then, Joe had taken it upon himself to "re-map the world" before his disappearance one night into Lake Superior. For Harrison, this is slightly less than terra incognita, recalling as it does past thematic forays, but my noting this shouldn't be construed as carping; Harrison approaches his ideas like a sculptor chipping away at an unseen ideal.

Other familiar territory is visited in "Westward Ho," the collection's second novella. Harrison's Brown Dog, a ne'er-do-well Michigan Indian, first appeared in an eponymous novella in "The Woman Lit by Fireflies." Brown Dog is Harrison at his comic best: A hapless, rambling, vulgar antihero, Brown Dog is nothing less than the Don Quixote of the Upper Peninsula. In this latest episode, Brown Dog trails a stolen bearskin to Los Angeles and falls headlong into that city's skanky stew of screenwriting rummies, plasticky starlets and lecherous bigwigs. Harrison's wit -- caustic, coarse and utterly charming, like that of a crazy old goat of an uncle spouting stories from afar -- is as whetted here as ever; you hardly notice the fervid intelligence clicking away in the background.

Yet the collection's final entry, "I Forgot to Go to Spain," glows brighter than even these two novellas combined. "I Forgot to Go to Spain" recounts the impromptu effort of a well-heeled, 55-year-old author of "Bioprobes" -- "those hundred-page intrusive biographies that fairly litter bookstores, newsstands, [and] novelty counters in airports" -- to reunite with a woman to whom he was once married for nine youthful days; along the way it occurs to him that he's never fulfilled an early ambition to see Spain. But banal summary won't suffice here. To crib a line from the narrator: It's "our dreams and visions that own true significance, not our petty ... details."

The novella all but boils over with dreams -- dreams of literature, love, loss, of all those epic L-words that too few writers seem brave enough, in these chilly times, to address on anything but ironic terms. "I Forgot to Go to Spain" is imbued with all the gravelly melancholy of a Tom Waits ballad, but it never once, despite that swarm of L-words, forces sentiment; the autumnal passion that drives the tale is never less than tactile. I could go on -- about the casual lack of geometry and astounding texture of Harrison's prose, about the delicacy of his characterizations -- but why? "I Forgot to Go to Spain" is above my twerpy praise. It's simply thrilling to see a writer reach for the sky and actually grab it.

Shares