This year, Social Security turns 65, the retirement age set by its own rules -- a milestone rich with ironic symbolism at a time when a growing chorus calls for retiring the system itself. Moving from a government system to private retirement accounts was once a fringe libertarian fantasy. Now, partial privatization of Social Security is a mainstream Republican proposal. In a mostly lackluster, idea-free presidential race, Social Security reform is one issue that highlights a basic philosophical divide between the two candidates. It's also at least one good reason to root for George W. Bush.

The grandmother of all middle-class entitlements, Social Security is undoubtedly the most popular government program in America, credited with dramatically reducing old-age poverty. Yet it has a major structural flaw that you don't need to be a whiz to grasp. The people who work and pay into the system are financing the benefits of today's retirees while relying on the next generation of workers to fund their future benefits. However, there are fewer and fewer workers supporting more and more beneficiaries -- both because people are living longer and staying around to collect the checks, and because birth rates fell sharply after 1960. In 1950, the ratio of workers to pensioners was 16 to 1; today, it's 3.3 to 1, and in 25 years it's projected to drop to 2 to 1.

The postwar baby boom followed by the baby bust has obviously worsened the problem. But any pay-as-you-go retirement program will always be at the mercy of such demographic vagaries. Surveys in recent years have found widespread popular support for reforms that would let people invest a portion of their Social Security contributions in the stock market. In a Washington Post/ABC News poll in September, 75 percent of registered voters 18 to 30 years old, 66 percent of those 31 to 44 and 57 percent of those 45 to 60 endorsed such proposals.

Naysayers -- from leftist economist Robert Kuttner to columnist Ellen Goodman -- are wont to dismiss the new enthusiasm for privatization as a myopic, irrational response to the booming economy and the soaring Dow Jones. (Some anti-privatizers greet every market downturn with barely disguised glee.) But when you know how well your money could do in the private market, it's pretty irksome to hand over 6.2 percent of your salary -- 12.4 percent if you count the employer's share -- to Uncle Sam for a promised annual return rate of 2 percent. It's especially galling for self-employed people like me, who have to shell out the entire 12.4 percent out of their own wallets.

In fact, estimates of how retirement savings would have fared in a private system are based on long-term trends, including the downturns and the crashes. Even before the current boom, from 1929 to 1996, the average annual return rate on market investments was about 7 percent.

Besides, the popularity of privatization (which began to show up in the polls in 1994) also has to do with a sense of a looming crisis. That bite taken out of your paycheck really hurts if you doubt you'll ever collect the reward, even at 2 percent interest. According to the latest report from the Social Security Board of Trustees, issued in March, by 2015 revenues from payroll taxes will not keep up with the benefits. To keep the checks coming, the government will have to use the "trust fund," the Social Security surplus accumulated since 1983 -- which, by current estimates, will be empty by 2037. Then, the only way to keep the system alive will be to hike the payroll tax, slash the benefits or both.

But that's only the half of it. There's no actual money in the "trust fund," only bonds the federal government has issued in return for borrowing the payroll-tax surplus to finance other operations. To draw on the trust fund for Social Security payments, those bonds will have to be redeemed -- for which, in the words of the Washington Post, "the government will have to find the money somewhere." Presumably somewhere in our pockets. Or somewhere else in the federal budget, which means squeezing other programs.

The man and woman in the street may not know the details, but they do know something is seriously wrong. In a June 1999 Gallup poll, nearly three out of five agreed that Social Security needs a complete overhaul or major changes.

In 1996, the Social Security advisory council appointed by President Clinton unanimously concluded that investing in the stock market was the only way to save the system, though it was sharply divided on how that should be done. Six of the 13 members wanted the government to invest payroll tax revenues; seven favored individual investment accounts, and five of those seven backed a plan that would allow people to put nearly 80 percent of the employee share of the Social Security tax, or 5 percent of their earnings, into private retirement savings. That's considerably more radical than Bush's plan, under which only 2 percent of earnings, or 33 percent of the employee share, could be diverted into individual accounts.

Some would go much further. The Cato Institute, a libertarian think tank in Washington (where I have an unpaid position as a research associate), champions a gradual transition to a fully private pension system based on the Chilean model. Social security privatization in Chile, launched in 1981, could be seen as tainted by its association with the Pinochet regime. Still, the fact remains that these reforms have been highly successful; they have won converts among initially hostile labor leaders and inspired several other Latin American countries, including Argentina and Mexico, to adopt similar programs. Chilean workers are required to deposit 10 percent of their salaries into personal savings accounts, managed by private investment companies that are subject to government approval and regulations prohibiting high-risk investments. An additional 3 percent goes to disability insurance. A government safety net guarantees any retiree a minimum income equal to 40 percent of average wages -- similar to the average benefit in the United States.

The real question is not whether a privatized retirement system would work better, it's how to get there from here -- how to allow workers to take their money and opt out of the state-run system while preserving the benefits due to retirees and those nearing retirement. Bush has been accused of ducking the tough issues, and it's true that he hasn't done a very good job of explaining his plan. Many privatization proponents argue that the massive infusion of money into the market would spur economic growth and boost tax revenues. If that's a little too iffy, the budget surplus offers an excellent opportunity to help pay for the transition. (It won't be cheap: economist Paul Krugman estimates that Bush would need to put aside half a trillion dollars out of the surplus to pay for transition costs.)

Meanwhile, Al Gore decries Bush's limited privatization proposal as "risky," while promising new benefits that would worsen Social Security insolvency and ducking tough questions about his accounting at least as much as Bush does. A parody of the presidential debates making the rounds of the Internet, in which Gore proposes "changing the laws of mathematics to allow us to give $50,000 to every senior citizen without having it cost the federal treasury a single penny until the year 2250," is not so far off the mark.

An article Tuesday in the Washington Post -- which has endorsed Gore and can hardly be suspected of bias against him -- points out several serious problems with Gore's approach to Social Security reform. It concludes, "Without saying so directly, Gore would have the country wait to see if the anticipated crisis in Social Security really exists." Some economists do, in fact, believe that everything will be fine if productivity growth outpaces the Social Security trustees' cautious predictions; but this head-in-the-sand approach still sounds pretty risky.

Moreover, Gore wants to draw on general revenues, not just payroll taxes, to help finance Social Security. As the Post notes, "This would place the retirement system in competition with defense, healthcare, education and other programs for possibly scarce resources. Social Security was set up to be self-financed through the payroll tax so it wouldn't be subject to such political pressures." Under Gore's plan, retirement benefits may be safe from the whims of the market but not from those of politicians. And, unlike Bush's proposal, which would also require massive short-term infusions of cash, Gore's approach would not provide a long-term solution to Social Security's structural flaws.

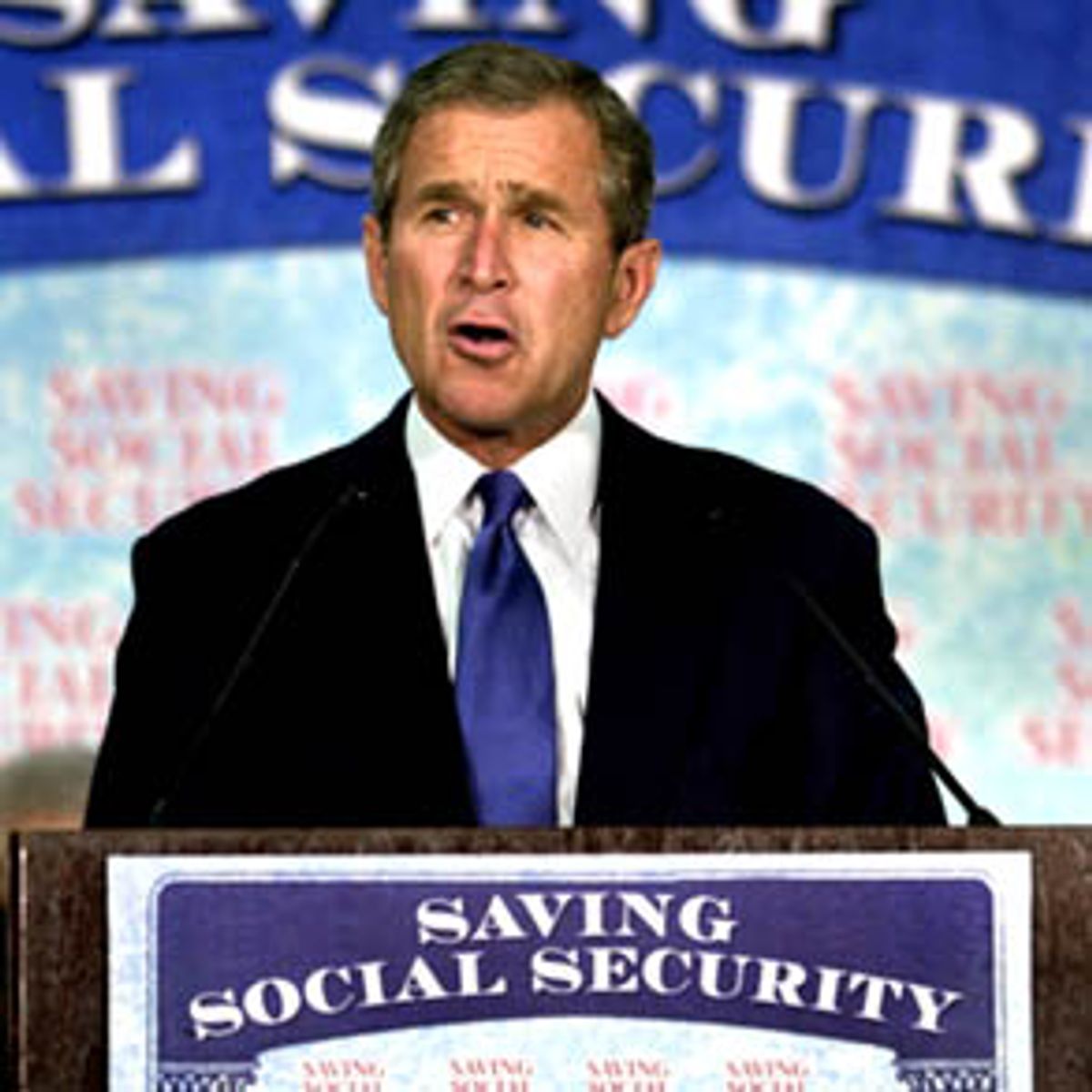

Of course it would be nice if Social Security privatization had a spokesman other than Bush; the man probably couldn't make a convincing case for celebrating Mother's Day, let alone privatizing retirement benefits. Perhaps it isn't very smart for him to talk about using the budget surplus for a big tax cut in the same breath that he talks about using it to finance Social Security benefits during the transition. But Gore's handling of this issue has been truly pernicious. What he proposes is the equivalent of doing nothing about a tumor that is more likely than not to turn cancerous. Worse, he has sought to demonize the very idea of privatization and to discredit it as a crackpot right-wing notion, conveniently forgetting to mention that it has been championed by quite a few eminent Democrats -- including Sen. Daniel Patrick Moynihan of New York, Sen. Bob Kerrey of Nebraska, and Gore's own running mate, Joe Lieberman. That is, the old incarnation of Lieberman, before he was picked as Gore's running mate and dropped his politically incorrect beliefs.

At some point, discussions of Social Security inevitably get bogged down in competing numbers, formulas and economic projections. Each side brandishes its own calculations and accuses the other either of panic-mongering or of excessive optimism. But perhaps, in the end, this debate is about philosophy, not economics.

The reason Gore so adamantly opposes any steps toward privatization, I suspect, is not just that he's pandering to the senior citizens (well, that too), but that he viscerally dislikes reforms that would minimize the state's control over a major sphere of American life. On some fundamental level, he really does believe that government knows best.

The rhetoric of many other privatization opponents shows an even more ideological hostility to markets (one even comes across such comical clichés as "the shark-infested waters of Wall Street") and individualism. In a New York Times op-ed column in May, Princeton economist and Gore advisor Alan Blinder wrote that "universal social insurance is one of those precious ties that bind our society together," forcing the affluent to share their wealth with the less fortunate, and that "privatization, whether partial or total, would weaken that tie."

Never mind that privatization critics like Blinder are unabashedly condescending to the poor, presuming that they won't be able to invest wisely. And never mind that in many ways, the current Social Security system actually robs the poor to pay the rich. Yes, lower-income workers get a higher dividend on their contributions, but they also pay a higher portion of their income into the system because earnings above $76,600 a year are exempt from the payroll tax, as are other forms of income such as capital gains and interest from savings or investments. The poor are also likely to get less out of the system because, like it or not, they generally do not live as long as the well-to-do. (In a privatized system, any retirement savings you don't live to collect would go to your heirs. In the current government-run system, the surviving spouse gets only 50 percent of the benefits and adult children get zilch.) While they live, the elderly poor are, not surprisingly, far more dependent than the affluent on Social Security benefits, since they are far less likely to have savings, stocks, and private pensions. So, if Social Security goes bust, the poor will suffer much more.

Unlike some of my libertarian friends, I believe we have an obligation to provide a safety net for the less fortunate, and that the government is often the most effective vehicle for doing so. But why not do it honestly? If we're going to help those who can't help themselves for various reasons, let's pay taxes explicitly allocated to such programs. If we're setting money aside to take care of ourselves, then let's have a real savings system in which that money belongs to us. Social Security is based on the illusion -- or, to put it more bluntly, the lie -- that the payroll taxes we pay aren't really taxes but contributions toward our retirement.

Besides, while mutual care may be a noble principle, so is freedom of choice and the ability to control the fruits of our labor. Bush may not sound very persuasive or passionate when he talks about empowering ordinary people, but personal savings accounts would be a real form of empowerment.

A couple of years ago, in a diatribe against those who would hand over our retirement trust fund to those Wall Street sharks, psychologist Theodore Roszak -- an erstwhile prophet of the 1960s Age of Aquarius -- angrily charged that the "privatizers" hate Social Security because it "stands as evidence that self-interest and the profit motive cannot be relied on to provide for the public good."

But maybe it's the other way round. Maybe the anti-privatizers hate privatization because its success would stand as evidence that self-interest and the profit motive (with some regulatory protections) can do more for the public good better than idealistic but ill-conceived bureaucratic schemes.

Shares