Aside from the late John Huston, that titanic presence known for translating writers such as B. Traven, Herman Melville and James Joyce to the screen, there may be no greater cinematic savior of scribes than director Philip Kaufman. Among his relatively small output of motion pictures (he has directed 11 since 1965), Kaufman, 64, has made films drawn from the work of Tom Wolfe ("The Right Stuff"), Henry Miller ("Henry and June"), Milan Kundera ("The Unbearable Lightness of Being"), Richard Price ("The Wanderers") and -- eek! -- Michael Crichton ("Rising Sun").

Now, the Marquis de Sade's getting the Kaufman treatment in "Quills." Geoffrey Rush is Sade as rock star, prancing about his cell in the mental asylum at Charenton like an 18th century version of Mick Jagger. This literary mad hatter goes head-to-head with Michael Caine's malevolent, black-clad, prude turned torturer Dr. Royer-Collard, and in the resulting conflagration Kate Winslet's starstruck washerwoman, Madeleine, and Joaquin Phoenix's sympathetic, tormented Abbé Coulmier, the liberal, do-gooding director of Charenton, are torn asunder.

This is literature at its most dangerous and depraved. Instead of the watered-down product of modern-day pedagogues who play artist in their university cubbyholes, we get the real thing -- the Father of Sadism, imprisoned for the product of his scandalous pen and willing to defy despotism to the death. Forevermore, Rush's Sade will be the model for the more outrageous class of aspiring scribblers. And for this we owe Kaufman and screenwriter Doug Wright (whose play is the basis for the film) a debt of thanks.

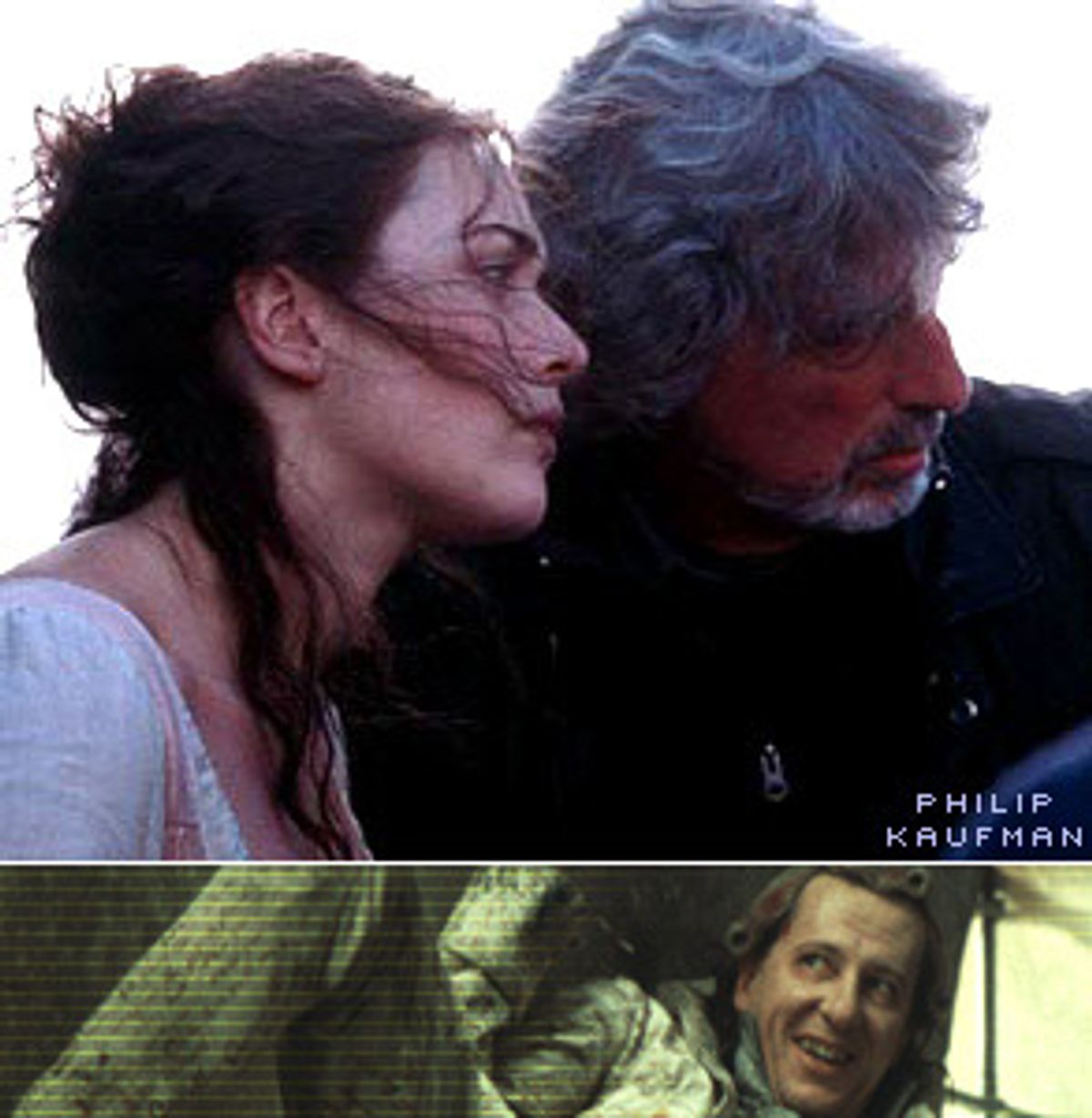

I talked with Kaufman as he sat sipping a glass of ginger ale, dressed in black, his gray-trimmed, hawklike countenance reminding me so much of "L.A. Confidential" director Curtis Hanson that I'd assume the two were brothers if I didn't know better.

You seem attracted to stories about and by writers. Why?

I really don't know. I read, therefore I'm interested in writers. The truth is, I'm drawn to all kinds of things. I was drawn to this because I thought it was a terrific story when it was sent to me. I liked the sort of game that was at the heart of it -- the game of expression and repression of expression, heightened expression countered by heightened repression and so on. And I liked this extreme character of de Sade. I guess I'm attracted to extremes because I think they help you define the center. Joaquin is the center of the piece, and he's defined by the extremes on both sides of him.

It just seemed to me to be a great story, set back in its time but something that seemed to have relevance for our time. Now that the film is coming out, it looks like we're back in another time where repression of expression is all the rage.

That theme of repression and control seems to be of great concern to you.

It does concern me. Certainly "The Unbearable Lightness of Being" is all about trying to force writers to say certain things, about that totalitarian mentality. In our case, if we were doing the Humpty Dumpty story, that totalitarian mentality would want you to say, "And all the king's horses and all the king's men miraculously, through cooperation and solidarity, put Humpty back together again." The very people who were railing against communism in a way want to create the same kind of bland society, but based on capitalism. The danger is not so much in the economic structure of a society but in its intellectual structure.

Is there something in your experience, other than being an artist, that has given free expression such significance for you?

There are many ways into that question, and I don't know that it's so psychological. We have a thing in the Declaration of Independence -- the "pursuit of happiness," it's called. It's not saying we're entitled to happiness but, rather, its pursuit. And it should be great fun along the way. To me, thoughts are fun and art is fun. The strength of our society should not be idle entertainments but the joy of pursuing ideas. Certainly it becomes clear after a while that happiness is not just having money. You can have a lot of unhappiness by not having money, but the reverse is no guarantee of happiness.

I don't know if I can give you any deep neurotic reason for wanting to pursue these things. In some ways, "Quills" is about a writer, but in some ways it's even more about the Abbé Coulmier, the character played by Joaquin Phoenix, a liberal guy trying to create sanity in the asylum through painting, music and all forms of art.

The Marquis is in a sense sitting on one shoulder, goading him on, irrepressible. He's the force of art whispering in his ear. In the other ear is Michael Caine as Dr. Royer-Collard, who is in some ways the force of this primitive science, "the doctor" sent in by the state, or Napoleon, to repress the Marquis.

Joaquin, the central spirit, represents us. He's trying to drive his vehicle down the road, and sitting in the rearview mirror behind him is the ever-voluptuous Kate Winslet. It's a tale of a man caught in the middle, and his obsessive relationship is with the Marquis, which is one of the great romances of the movie.

With whom do you identify most in the film?

I feel close to the Abbé in some ways. But in some ways I feel closer to Madeleine. She's the character who finds some sort of joy in the Marquis' literature, whereas the Abbé doesn't really find much value in it. Is there something to be said for the writings of the Marquis? Is there something to be said for pornography? And is there something to be said against both? I hope our film is balanced and rich enough to encourage debate and discussion. How potent, how virile, is art? Can it influence people in bad ways? Or is repression a far worse thing?

You know Madeleine is the most noble, least neurotic character in the whole piece. Some of her observations about the Marquis echo writers as diverse as Simone de Beauvoir, Angela Carter and Camille Paglia -- women who've written about him as well as men like Octavio Paz and Luis Buñuel. I have to go back to Doug Wright's thesis -- that by giving a rebirth to the most notorious writer of all time we might be able to shed light on this question of repression and self-expression.

The passages of Sade's work that are read in the movie are pastiche and not from his work at all. Why? Was there any attempt to soft-pedal Sade?

Doug wrote those passages in part because he didn't have rights to the translations, but he wrote these stories truly in the spirit of the Marquis, using the vocabulary that the translations have used. What's really interesting about that is that a lot of these words that were incendiary in their time now seem almost harmless and laughable, because they have this archaic quality. We went through all of that with Lenny Bruce. He was sort of hounded to death because of "fuck." Now there's not a comedian in the world who doesn't stand up in a nightclub and use that word. Children even use the word. But in Doug's telling, "backside" is one of these shocking words for Napoleon as he hears it.

I don't think we soft-pedal anything. These stories are pretty extreme, but the way we're telling them makes them somewhat more humorous. The very first story is a bishop who lifts up a woman's dress, puts a wafer on her privates and plunges his "pikestaff" into her "very entrails." And there's the story the Marquis tells through the walls to the other prisoners of ripping the prostitute's tongue out and cauterizing the wound with fire. That's in the nature of a Sadeian story.

Where the film really becomes a sadistic, Sadeian tale is when the Marquis' tongue is being cut and turned against him. Some people just want it to be a "Tom Jones" romp. But the story, in order to validate itself, has to take these dark turns. The metaphor is the birth of a writer, played by Joaquin, who arrives at the end of the film as a storyteller. But it's the Marquis' voice who speaks through him from beyond the grave, saying, "I leave you now with the Abbé Coulmier, a man who found freedom at the bottom of an inkwell and the tip of a quill."

Geoffrey Rush said you encouraged him with these visions of a dissolute rock star holed up in the Ritz-Carlton. How did that vision of Sade take hold?

Partly in our talking about it, partly from Doug's original material and partly from myself thinking of Mick Jagger down in the lower depths. But a lot of it comes from Geoffrey Rush. I remember the day when Geoffrey finally put on the Marquis de Sade suit and came onto the set and walked around in those white heels. You could just feel we were up at another level.

Of course, I thought Geoffrey was perfect for the Marquis. When I first met Geoffrey, I found him funny, witty. He's physically interesting; he's provocative, thoughtful; the words go on and on. He approaches everything in a very original way. He was reputed to be Australia's greatest theater actor and always looks different from movie to movie -- you can barely recognize him sometimes. He brought a lot of humor and sophistication to the role.

You've said previously that Sade was not "the Hannibal Lecter of literature." Were you worried about portraying Sade as a monster?

Yes, I definitely wanted to avoid that. For instance, there's that scene where Kate goes into the Marquis' bedroom, approaches his bed and throws back the curtain to see a skeleton. The Marquis says, "Oh, did I scare you?" And she says something like, "Scare me? I'm twice as fast as you." Right away, she pooh-poohs him, and we realize there's a human dimension to this guy. Whatever you think of de Sade, he was a complex figure and we should not look for easy answers with him. He was, strangely perhaps, against the death penalty, and he was never put in prison for murders or anything like that. In a sense, he was imprisoned for his writing -- really by his mother-in-law, for more complex reasons than we can go into.

When you took on this story, were you looking for a way to comment on current events?

Well, it just had resonances the minute I read it. I read it during the Ken Starr-Clinton fiasco. To my mind it was a fiasco because there was so much hypocrisy on the part of the pursuers. And it culminated in Starr's publishing this report that became an instant bestseller and was all over the Internet, much like Dr. Royer-Collard does at the end of the film when he publishes the Marquis' works.

I don't know if we did that scene because of the Ken Starr parallel, but it seemed like the proper ironic twist. Just a couple of weeks ago in the New York Times, they had that big front-page article about porno and these huge corporations that market it. We could open that door (indicating a TV cabinet nearby), flip on a channel and see porno far worse than anything we put in the movie. It's the deep hypocrisy of those who would purify the culture. A lot of people behind this represent the most conservative forces. If there's money to be made, they will do it. So Michael Caine's character in a way mirrors those forces. I also like the fact that Caine ends up with Charlotte the Squealer, the Linda Tripp of the film, the woman who tattles on Madeleine because she's smuggling the Marquis' works out of Charenton.

You got an R rating for "Quills," but there's another film out right now, Requiem for a Dream" by Darren Aronofsky, that doesn't seem any more objectionable and yet got slapped with an NC-17 by the Motion Picture Association of America. You had trouble yourself with the NC-17 rating on "Henry and June" -- do you know why "Quills" coasted by with an R?

I have no idea. You know, we got an R and I was just happy I didn't have to go through an appeal. On the other hand, I think the ratings system needs some reworking. I don't think this is a movie parents should bring underage children to. My wife has this line: "This is not a film for children of all ages." It's not a Disney movie, obviously, and some people are going to be offended by the sexuality. If it's going to be too strong for them, they shouldn't come to this movie.

Others might find it provocative, thoughtful and sexy. But to my mind that's an adult audience. Not every movie I make do I feel that way about, but certainly I feel that way about "The Unbearable Lightness of Being," "Henry and June" and this film.

What exactly would you do to rework the ratings system if you had that power?

I don't know. I just think it needs to be thought out a little more carefully. Maybe there needs to be a couple of different kinds of R's. If there's an NC-17, it should not be the equivalent of the X rating. We should open up the adult categories more and more and encourage Americans to see adult-themed movies. I think otherwise we deny ourselves movies about sexuality. I mean, everybody's thinking about sex all of the time. Look at daytime TV: "Oprah" and all of those shows talk about sex constantly. And yet we pretend we're not interested when we're talking about movies, where sex is depicted as just a visual with two beautiful bodies coming together and has nothing to do with the mentality of sex or with enlarging the libido.

It's almost as if the more a movie's cleaned up, the more pornographic it becomes. It's anti-human, and more like jerking off to magazines. Whereas European films have traditionally been able to go into adult relationships. I think there's a huge audience in America for those kinds of films.

The odd thing is that anyone of any age can walk into Barnes & Noble, pick up Sade and read the most grotesque, macabre depictions of sexuality ever imagined. Why is it that it's the visual that disturbs people?

You know, I don't think it frightens people. I think there are people who really want to control the culture, and it's a holdover from Puritanism. But movies make a lot of money, and there are persons who want to get in and control the content of those things.

On the other hand, I think there's a good argument for not marketing certain things to children -- a lot of that is valid. The danger is if the argument is not held within close boundaries. You'll see Joe Lieberman arguing correctly against test-marketing R movies with younger children; there's something terribly wrong about that. But the other side says, "It's not just the marketing. We ought to go into all Hollywood movies and all content." That's where it gets really scary. A lot of that comes from the urge to control others in every way. Often it's from people who are the deadest inside, the most desiccated personalities.

The perfect example is the Grand Inquisitor scene in "The Brothers Karamazov," where Christ comes back to earth and the Inquisitor says he has to be sentenced to death once again because he's ruining the setup -- that people need miracle, mystery and authority, and he's going to destroy everything. Similarly, the Marquis is presented in this film as someone who would disturb the status quo and therefore must be kept imprisoned.

Are there any artists of our age who challenge society in the way Sade did?

Well, Doug Wright said he wrote the play because of Robert Mapplethorpe and Jesse Helms. They were engaged in this death-lock struggle, and theirs was a symbiotic relationship where they actually needed each other. As for me, I think Henry Miller was important that way, as well as Lenny Bruce, James Joyce and D.H. Lawrence. All of those people were banned and repressed because of what they wrote and said.

I hear your next film is going to be about Liberace.

I hope we get to do it. He's another one of these extreme characters I'm attracted to. Right now we're working on the script.

Any idea at this point of whom you want for Liberace?

A friend of mine named Robin Williams would love to play him. He was in my office not so long ago. There was a picture of Carol Channing and Liberace we were looking at, and he did this brilliant dialogue between the two of them. We all fell over on the floor. In a way, he has lived the Mr. Showbiz life himself, so there's an aspect to the character he would really understand.

Shares