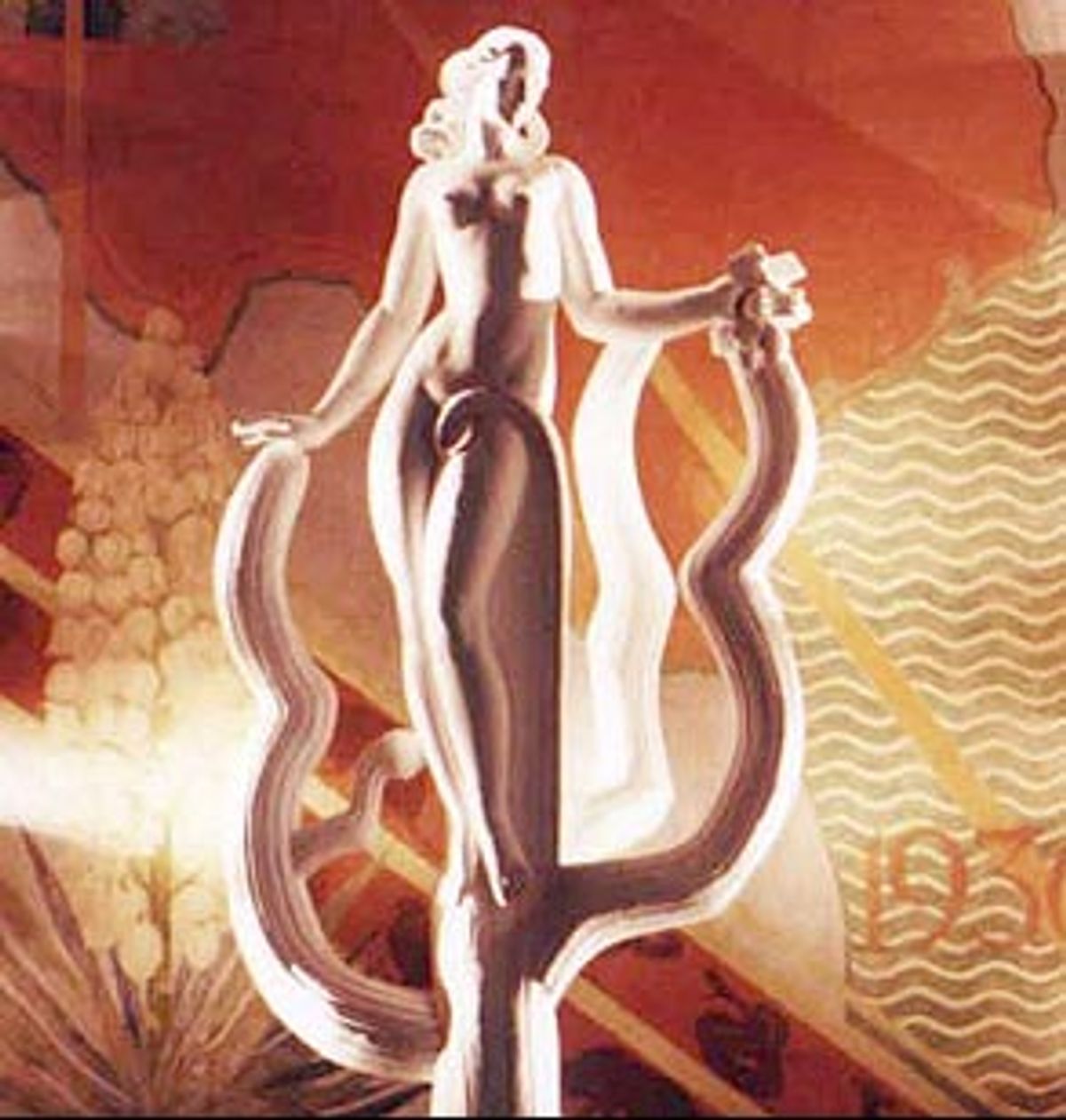

The 1936 sculpture that graces the entryway of the Women's Museum: An Institute for the Future depicts a woman perched atop a cactus. Lean and fetching, she towers 30 feet in the air and except for the narrow ribbon of fabric draped across her nether regions -- and a giddy smile -- she is buck naked.

The "Spirit of the Centennial," as she is called, conveys a sentiment more akin to "Hello, sailor" than "Hear me roar," and fittingly so. "This isn't going to be a bunch of feminists running around," promised museum CEO Cathy Bonner two years ago, when the museum was in its early planning stages. She wasn't kidding.

The Women's Museum, which opened last month, is an institution as notable for what it omits as what it contains, a watery survey of female accomplishment that for the most part glosses over the conditions -- i.e., a couple of centuries of sexual inequality and its attendant ills -- that make such an institution necessary in the first place.

Heavy on wall text and light on historical artifacts, the exhibits perform a careful two-step around issues like abortion, sexual harassment, rape, domestic violence and pornography that might be construed as unpleasant or discomfiting. While sepia-toned struggles (such as the suffrage movement) get their due, when it comes to present-day battles, the museum is a monument to the adage "If you don't have anything nice to say, don't say anything at all." The agenda is stubbornly, willfully, relentlessly positive -- a feel-good survey of female achievement that's as easy to swallow as a multivitamin.

It also is the manifestation of a mild-mannered brand of feminism that has long flourished in the South, often in direct and slightly miffed opposition to the movement establishment centered in the Northeast. Dedicated to making peace with a man's world, the women behind the Women's Museum don't shrink from the feminist label, but they proudly reject confrontational tactics.

"What we're saying is women can do anything, and if they're going to do it, they must do it for themselves," explains executive director Candace O'Keefe. "It is about looking at the positives rather than the negatives -- what we have done and what we can do rather than what we haven't done and what we couldn't do."

Visitors to the Women's Museum are invited to absorb the bright side of women's history through a timeline of important moments (from the matrilineal society of the Pueblo Indians in the 1500s, to the opening of the Women's Museum) and a pantheon of 38 "Unforgettable Women."

An exhibit on "Organized Movements" lumps groups like MADD, AARP and the Girl Scouts together with groups devoted to women's rights, placing reproductive freedom and Thin Mints on equal footing. Successful women in fields ranging from inventing to comedy are included, with the emphasis on breadth rather than depth. There also is a smattering of curios -- one of Amelia Earhart's flight jackets, a WNBA basketball -- among numerous bits of wall text, photos and an occasional video clip.

It would be easy to forgive the Women's Museum its limitations if it were a more traditional institution, focused on preserving the past rather than making a sociopolitical point. But the museum follows what is called in curatorial circles the "forum" model as opposed to the "temple" model. (The former type is devoted to fostering a sense of collective identity; the latter is a repository of relics and treasures, such as New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

The Women's Museum, with its rather perfunctory showing of objets d'art, explicitly promotes a mild-mannered social agenda. Ever mindful of their numerous corporate sponsors (all of them prominently and repeatedly acknowledged throught the space), the organizers dodge the visceral and intellectual challenges of feminism in a self-defeating bid to ensure that the museum does not turn into what academics like to call "contested terrain."

In their planning of the institution, organizers also had to consider the conservative social climate of Dallas. As Debra Michals, the museum's content director, puts it, "This is what happens when national history meets regional politics."

Which begs the question: What is the first national women's museum doing in the Bible Belt in the first place?

History, we're forever being reminded, is written by the victors, and in the tricky game of corporate fundraising on which our cultural institutions have come to depend, the Texan founders of the Women's Museum have plainly routed the competition. Similar projects planned for Washington, Denver and San Francisco have struggled for years to get off the ground (all can be charitably described as "museums without walls"), and another slated to be built in New York's Battery Park City has just entered the planning phase. Meanwhile, it took the Texans just four years to whip up their Women's Museum.

Much of the credit goes to Bonner, a 50-year-old marketing consultant, who hatched the idea, found the building, recruited a board of directors and raised $30 million. She did this while running her own business as a marketing consultant for state college loan programs and pursuing a master's degree.

Bonner is often described as "a force of nature," and she may well be. But just as important, she has long acted as the director of the Foundation for Women's Resources, an organization dedicated to tutoring women in "leadership" skills, electing them to public office and placing them on corporate boards, which makes her a central figure in a considerable old girls' network stretching from Austin to Washington.

The Texans' triumph becomes all the more impressive -- or troubling -- when one notes that, aside from spearheading a traveling exhibition on women in Texas history in 1979, none of the project's founders has any real background in women's studies, museum administration or curatorial work.

Their early attempts to forge bonds with the scholarly community met with little success. "It's like, 'Who are you to be doing a museum? You're not a curator and you don't have a degree in this!'" Bonner recalls. "We've joked that we'd like to do one of those yellow books, 'Museums for Dummies,' after this is all through, because we don't know if we're doing it the right way -- we're just doing it our way. And maybe ignorance is bliss."

The timing, at least, has been impeccable. Museum attendance is booming (up 40 percent in the last decade), expansions are underway and new institutions -- everything from the Museum of African-American History in Detroit to the Museum of Sex planned for New York -- are sprouting all over, funded by a bull market and the boomer generation's midlife yearning for monuments to call their own.

But these heady developments have been accompanied by a troubling counter-trend. While the families thronging to the Newseum, the Getty Center and the Rock and Roll Experience may barely remember the fierce culture wars that rocked museums in the late '80s and early '90s, administrators and curators never forgot them. The upshot is that Enola Gay is out; Giorgio Armani is in and the delicate task of deconstructing our nation's cultural myths has been left in the trusty hands of street preachers and Ph.D. candidates.

One member of the latter category is Debra Michals, who balanced her work as content director for the Women's Museum -- compiling the academic raw material that would be whittled down into 15,000 square feet of permanent exhibits -- with the writing of her dissertation on female entrepreneurs for NYU's American history department. Michals was never actually employed by the museum itself; she was a freelancer, working for the museum's exhibit design firm, Whirlwind & Co. in New York.

In an arrangement that's highly atypical in the museum world -- where even temporary exhibits are hammered together by teams of Ph.D.-packing curators -- Whirlwind, headed by the husband-and-wife team of David Lackey and Terren Baker, was given responsibility not only for designing the exhibits and overseeing their fabrication but for thinking them up in the first place. "It is unusual," Baker admits, adding, "We feel very privileged to have this level of input." While they planned and configured the displays, Michals did the scholarly legwork.

Although Dallas didn't immediately strike her as the ideal site for such a project, she eventually came to like the idea. "In a way, the fact that it's in Dallas makes it all the more radical," she says. But Michals adds that reconciling her own vision with the more conservative sensibilities of the museum's founders wasn't always easy.

One area of contention was an exhibit called the Myth Maze, which Michals and the Whirlwind team conceived as a space where museum-goers' gender biases would be systematically dismantled. As Michals recalls, "It was going to be a developmental life trip through all of the ideas -- social, biological, psychological and so forth -- that postulate what makes us female, from birth to death. It was a way of getting feminism, poststructuralism, gender studies, theoretical studies into the museum in a way that would work with the exhibit design." It was, Michals says, supposed to cover everything from 'blue is for boys; pink is for girls,' to testosterone and estrogen theories, to rites of passage like development of breasts, menstruation and loss of virginity.

"Well, you can see where the Dallas Red-Alert Meter started flashing!" says Michals. "And it wasn't just the people I was working for, because they liked a lot of this stuff. But it wasn't playing with the focus groups. The feeling was, 'I don't want to be next to my husband, wife, mother, father, sister, boyfriend -- fill in the blank -- when I read about menstruation.'"

Adds Whirlwind's Baker: "A lot of the maze had to do with sexuality, and basically, what we found out was that sexuality was not an issue that people wanted to get into in a public space."

The reconfigured exhibit, now bearing the less unsettling name "The Maze," is a collection of wall panels and vitrines. In one case, the same baby picture appears in two frames, one pink, the other blue. Barbara Kruger's famous image, "Your Body Is a Battleground," turns up near a collection of "Sheroes," female action figures donated by executive director O'Keefe, who is an avid collector of Wonder Woman memorabilia. Overall, the tone is something akin to "Ripley's Believe It or Not" as scripted by Cathy Guisewhite (whose "Cathy" cartoons, appearing on two panels in the Maze, are among the most incendiary material in the museum).

The fear of being pegged as anti-male created further problems. "I wanted to mention how all embryos start out female, and after about nine weeks, the hormones kick in and sex is determined," says Michals. "This is a scientific fact. Apparently, there were men who really flipped out about it. One man said, basically, 'I know I didn't start life as a woman.' In the end, we pulled the whole entry." As for a vintage "Male Chauvinist Pig" cartoon calendar from 1974, it has yet to see the light of day.

Likewise, references to sexual orientation -- such as Michals' delicately worded mention that pioneering journalist Dorothy Thompson "had relationships with men and women" -- didn't make the cut. "They felt if the Texas market saw that somebody was a lesbian, they would not even care what else she did with her life, and they wouldn't take their kids," Michals explains, adding, "Look, they know their market, I don't."

At times, a spirit of compromise prevailed. Michals' plan to include disgraced evangelist Amy Semple MacPherson and voodoo queen Marie Laveaux, as well as alternative spiritual movements such as goddess worship and Wicca, in the religion exhibit prompted some hand-wringing, but when she guaranteed that mainstream faiths would be the primary focus, the Texans seemed mollified (though it should be noted that Semple MacPherson's brief bio makes no mention of her downfall).

While Michals was pleasantly surprised when her examination of the nuclear family as a postwar invention sailed through the vetting process without a hitch, she encountered heated resistance to a reference to the shrinking average body size of Miss America contestants over the years (which, according to a Johns Hopkins study, now meets the World Health Organization's standard for undernutrition).

As it happens, one of the Dallas curators is an avid fan of pageants. "I wanted to show things like the Miss America protest of 1968," Michals recalls, "and she wanted to show all the scholarships and the good things these women have done with their lives."

Michals lost that battle. In the Maze, museum-goers can gaze upon an authentic Miss America trophy cup as well as the sheet music to "Here She Comes," but ultimately, the tiara's gleam remains unclouded. "Texas is pageant country," Michals pointed out with a shrug.

(After much searching, I did discover one mention of the Miss America protest, a watershed event in the history of feminism, in the Women's Museum. In a case filled with Gloria Steinem memorabilia, one can view a galley proof of a 1989 editorial Steinem wrote for the New York Daily News in which she spells out the feminist objection to pageants. You've got to press your face up to the glass to read it, but it's there.)

The museum's sponsors maintained veto power over some exhibits. "I wrote the health timeline," Michals recalls, "and I had to send it to Johnson & Johnson [sponsors of the museum's Pathways to Health exhibit] for approval." One sticking point was a mention of aerobics tycoon -- and longtime political pariah -- Jane Fonda. "We kind of negotiated with them," Michals adds. "They were very cooperative."

Shortly before the museum's opening, a showdown occurred, predictably enough, over abortion. At issue was the biographical sketch of Steinem, one of the museum's Unforgettable Women. The text referred to a radicalizing event in the Ms. magazine founder's political development, a 1969 speak-out on abortion that led Steinem to embrace the women's movement and to share the story of her own abortion.

When Michals heard that Texans were planning to delete the reference, she placed a call to Steinem's office. "I thought it was an important part of her history," she says, "and I wanted to see if Gloria agreed." Steinem did, and the line stayed. "You should have seen me dancing around my kitchen," Michals said. (O'Keefe denies that there had ever been a plan to keep the abortion reference out.)

Whatever the case, it's not clear whether visitors will appreciate, or even register, such gestures. On a recent Saturday afternoon, Carla Wilson, 22, and her friend Sharon Brunner, 23, stopped by to check out the exhibits.

"It would have been nice if they could have had more stuff on current events, things like date rape and abortion," said Wilson. "Stuff that concerns us now. Stuff that we're still fighting for."

Brunner took issue with the museum's top-down approach to history. "It was all celebrities, big name people who've led movements," she said. "They didn't tell anything about the common woman -- what was her experience? Just a few little things, like 'Here's some Tupperware!'"

In addition to running counter to academic trends, which favor the sort of social history Brunner found lacking, it might be argued that the Women's Museum's great-woman focus -- essentially replacing the traditional pantheon of male elites with female counterparts -- actually carries a negative subtext. As Edith Mayo, curator emeritus at the Smithsonian, writes on the Web site of Washington's long-planned National Museum of Women's History (for which she acts as a consultant), "Simply adding women to traditionally male categories of achievement serves to reinforce the cultural assumption that they are the only arenas where success is worthwhile."

In other words, pointing out that there have been female as well as male entrepreneurs, for instance, does nothing to alter the perception that raising or educating children -- to name two traditionally female activities -- are somehow less valuable than starting businesses.

As for the museum's cheery focus, Brunner said, "A lot of it was like, ugh, empowerment. It's saying 'You can do everything men can,' when I really think that's a given. I think we're at the point when if you want to break some barrier, then just go do it."

Added Wilson, "It didn't make me go 'Girl power!' or anything. It was just like, OK."

Like any such institution, the Women's Museum reflects the attitudes of its organizers, and to understand its peppy, glass-is-half-full vision of women's history, it's instructive to go back to the origins of the Austin Foundation for Women's Resources, during the height of feminism's so-called Second Wave.

From the beginning, the seven Texan women who formed the group -- among them Bonner, Ann Richards and Sarah Weddington, who argued Roe vs. Wade before the Supreme Court -- found themselves philosophically opposed to their more radical feminist cohorts in the Northeast.

"Because we were Texan, we all did things in our own way," Richards explains. "You remember the famous burning of the bras that was going on in the Northeast? We didn't do that type of thing 'cause we all needed our bras."

(According to Steinem's Daily News galley proof, bra burning was a fiction from the start, invented by a New York Post headline writer as part of a story on the Miss America protest. Of course, Richards would only have known that had she been willing to press her face against the glass case.)

Lingerie aside, the Texans have always pursued their own, more pragmatic and accommodating brand of feminism. Their goal was never to overthrow or even transform the established, male-dominated order, but to infiltrate it. "We were much more politics-oriented than demonstration-oriented," Richards continues. "Our goal was to change laws and to change policy. Not in the sense of protest, but to figure out how we could get a piece."

To Bonner, the philosophical division was even more acute. "They always thought we were slow-talking dimwits," she recalls bluntly of the movement establishment.

Over the years, while New York's more radical, theory-minded feminists were beset by internecine squabbles, the Texans were busy tutoring each other in public speaking and working their way into the corridors of power. While the New Yorkers were inventing political correctness, the Texans were working to put Ann Richards in the Statehouse.

Today, with old school radical feminism apparently near extinction, the job of institutionalizing the history of women in America seems to have fallen to the Texas contingent, at least for the time being. And whatever the Women's Museum's flaws, it's very existence could be interpreted as a sign of progress.

After traveling to Dallas for the museum's inaugural gala, Michals, for one, came away "really impressed." As she sees it, "In the end, I think the museum is a decent collaboration of disparate views and political philosophies. They had a vision and I was hired to bring it to life, and I had my own vision and I was able to incorporate more of it than I expected. I'm really proud of it.

"The day after the gala," she adds, "the FDA approved RU-486. I was like, 'Can this trip get any better?' First the museum didn't suck, then RU-486 got approved."

Much earlier in the process, after her second day of work on the museum, Michals had a dream that, in its exaggerated way, seemed to sum up her awkward position as feminist scholarship's de facto ambassador to Dallas. In the dream, Michals constructed an exbibit on women's history (with the help of Gwyneth Paltrow, who'd inexplicably been hired as her research assistant). But when Michals returned to see it, she found an exhibit on Ted Danson, who once made his own black-faced foray onto contested terrain, in place of her work.

"Ted is in this pink Cadillac convertible," Michals recalls, "and he's waving at all these blond bombshells in bikinis, telling them to get in his car. Which they do."

Michals' blurbs about women's history, she discovered in the dream, were to be placed in the clouds around Danson's head. She went on: "So I say, 'Are you kidding me? This flies in the face of the very point of a women's museum! This is insulting to women, this is insulting to Ted Danson!'

"And the guy building the exhibit says, 'Does this mean you won't give us the history?'"

In its burlesque of intellectual compromise, this dream has actually proven quite prescient. Michals did ultimately climb into the pink Caddy and "give the history" that the museum organizers requested. They in turn reshaped that history into a chronicle of happy endings, ensuring that no hint of controversy would stomp on their empowerment buzz. They made it safe.

Even without Ted Danson.

Shares