My agent called me on a Sunday afternoon. He loved my script.

Get it?

My agent, David Saunders at Agency for the Performing Arts, called me on a Sunday afternoon and he loved my script. Hell, I didn't even know David existed on the weekend. I figured that on Monday they just took him out of the casket and he went directly to his dark office in that big building on Sunset. But, yes, that was his voice on the phone and he was saying all those things a writer dies to hear. First thing in the morning, he enthused, I would be on the Yellow Brick Road; a golden path only slightly stained by my seven years of hacking scripts that were made into bad movies by even worse directors, producers and actors.

The script went out, the responses came in, it was good. Very good. So good that super-producer John Davis ("Predator," "Grumpy Old Men," "Grace Under Fire") wanted Fox Studios to purchase it for him.

Davis' offices are in the really nice section of Los Angeles. As soon as I parked my car I knew this was the bigs. The underground lot was studded with BMWs, Benzes and other expensive German and Italian iron. Most people were in casual clothes, a sure sign that they were players -- they didn't give a rat's ass what you thought of them.

Standing at the portal to the Underworld, I glanced up at this imposing structure and couldn't help reminiscing on the whacked path that had led me here.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

Wavy-line SFX as we FLASHBACK TO:

INT. PRODUCER'S OFFICE -- DAY

YOUNG WRITER meets PROFESSIONAL PRODUCER. Some illusions are shattered.

My first ever industry meeting, filled with glorious anticipation, lasted all of five minutes and went something like this: "Mark, I read your script. You're a great writer. We can get dozens of writers like you. Get a better concept next time. A high concept." A what concept?

Let's define terms:

Spec script: Something you write on your own impetus that you hope someone will buy.

High Concept: A story concept that you can describe in 10 words or less (since most studio execs have the attention span of a Halloween pumpkin but aren't nearly as bright). Example: "I see dead people."

Producer: An entity (not necessarily human) who makes it possible for your spec script to be purchased by the studios.

Studio Exec: Another entity (see Producer) who takes your script up the studio's corporate ladder to the people who may ultimately make it into a movie.

Here's how it should work: I write a script on spec, a producer receives it from my agent, reads it, loves it and takes it to the studio with which he/she is affiliated. The studio buys it, makes it into a successful film and continues to pay me obscene amounts of money to write what I like.

Now forget all that, and you've got my career.

It was 1990. I wasn't all that young but I was fairly naive. I still believed in Santa Claus and reasonable Hollywood men and women. I was taking writing classes at a community college and had finished three scripts, two of which were science fiction. My goal was to bring better science fiction to the big screen. I wasn't having much luck. Seven out of the top 10 grossing films of all time have been sci-fi -- you'd think it would be an easy sale. Not so. Any producer who read my work liked the writing and hated the concepts. If it wasn't "E.T.," it wasn't really sci-fi, one producer maintained.

Fortunately, one of my rejected science fiction scripts, "Nemesis," got the attention of a company that was looking for new writers (new = non-union = cheaper than Writer's Guild). As a result, the company asked me to be part of a cattle call and pitch a concept for the sequel to "Relentless," a low-budget film about a guilt-ridden serial killer who wants to be murdered by the police. The sequel was supposed to be a variation on the original, but it had to be clever enough to catch the attention of the film company, Cinetel, a very successful low-budget company that makes five or six money-producing films a year, year after year, mostly by selling them to cable networks or going direct to video.

My idea for Cinetel's sequel: A serial killer who is not a serial killer is killing people who are already dead.

They bought it almost instantly.

I was contracted to write the script and for what seemed like a lot of money ($38,000 in various increments). They wiggled out of the last $10,000 payment by declaring that they hadn't achieved a certain contractual production goal. Were they lying? Don't know. Did I care? Hell, no. I made $28,000 for three months work. Do that a few times a year and you're living large.

The man who had directed the first "Relentless" was also going to direct the sequel. I saw him at an Academy Awards party hosted by Cinetel. Never having met a director, I was full of the promise of the future, having already mentally bonded with this man, professional to professional.

When I introduced myself to this (former porn-video) director, he told me flat-out that the script would never work -- this without reading a single word of something that I had barely started. He would give me four films by the famed Italian horror director Dario Argento. I wasn't clear what he wanted me to learn from them, but I was nevertheless supposed to watch them and call him so we could change the script -- even though he knew that I was contractually obligated to write only the concept that I had pitched to Cinetel.

If he noticed the urine running down my leg he didn't say.

Despite his intervention, I wrote the story I had pitched. Ultimately, he didn't end up directing the movie. Michael Schroeder, the replacement director, helped polish my script and make it visually stunning. Everyone lived happily ever after, right?

That could have happened.

The actor, Ray Sharkey ("Idol Maker," "Wiseguy"), who they pulled in at the last minute to play the bad guy, was someone who I respected and admired. The first words out of his mouth were less than reassuring.

SHARKEY: This is some of the worst shit writing I have ever seen. Who fucking talks like this?

As our relationship progressed from bad to worse, I soon understood why Sharkey was such a convincing bad guy: He was an asshole. He turned the filming of "Relentless II" into a nightmare of petulant rants.

I also learned a hard lesson. In the low-budget world, you only work with actors like Sharkey when they are on the downside of their career. By then, they are usually pretty grumpy fucks who hate the fact that they are doing a $2.5 million genre flick instead of a $100 million studio film. There are a lot of them.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

MONTAGE of SCENES

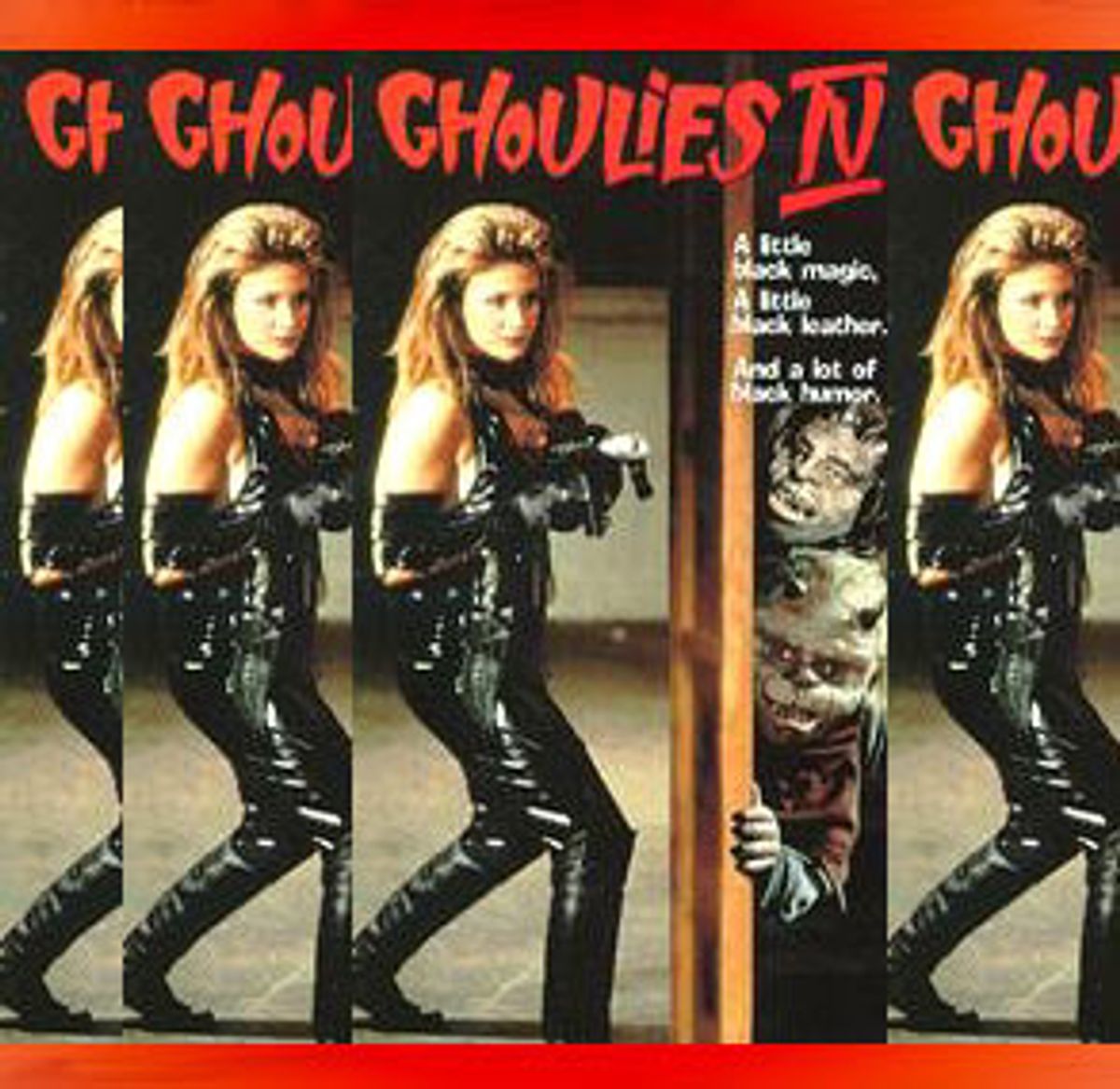

Cinetel and I proved to be a good match. Around town its creative director, Catalaine Knell, was called the Queen of B's. I was emerging as the King of Roman numerals. After "Relentless II" Cat and I collaborated on six more films, five of which were sequels. I was so busy at one time that I was working for two companies on three scripts, finishing one, starting another and polishing a third.

The movies were fast, fun and financially rewarding. Plus, the "B" moviemakers would take chances that studios would never dare. It was hard, sometimes frustrating work, and I was always proud -- until I saw the finished product, which most times made me cringe. Most times the movies I wrote made me cringe. There was always an excuse: bad director, alcoholic actors, no budget. But in the back of my mind I thought maybe I'm just not a very good writer.

But I had a good time, I made money and I didn't think about the future much. Eventually I developed a sense of humor and a fatalism about the whole process. How else do you cope with the following experiences:

And so on for seven years with dozens of assignments, hundreds of story meetings and 12 produced films. I was getting just a little burned out and beginning to think that I was relegated to writing sub-par, genre scripts that paid the bills but in no way helped move me forward either careerwise or, more important, creatively.

CUT TO: REALTIME

With my agent's blessing I took a gamble and stopped taking low-budget assignments to write what I wanted to write. "Arachnid" was a labor of love, my passionate homage to the creature flicks of the '50s, the kind of movie where a Man/Insect/Alien grows to epic proportions because of exposure to Radiation/Virus/Convenient Substance and takes over whatever Town/Island/Planet the small-time production company could afford. These movies, like "Them!" and "The Blob," were canonical masterpieces of "B" filmmaking. I knew, in this revisionist mood of Hollywood, that anything from 40 years ago was being given a new cloak of respectability. Throw enough money at something and you make it legitimate -- old television, old movies or old actors. With studio funding and the right creative urge, "Arachnid" could be a sci-fi classic.

And now, waiting to enter Davis' offices, I was actually on the doorstep of the magic kingdom. After too many years of scraping and bowing I finally had something that a mega-producer liked and wanted to take to a studio. How many times had I been this close? Actually, not many -- but the constant promise of this moment had kept me working hard. Even as my agent had slowly lost some of the enthusiasm we had shared in the earlier days of my career, I never faltered or wavered on my original goal of bringing intelligent sci-fi to the big screen.

I had been told in a phone meeting with one of Davis' key development people that Davis Productions intended to make "Arachnid" its next big summer movie. It was going to budget it at $50 million, minimum. That meant hundreds of thousands of dollars for me -- financial freedom. Plus, I would have the chance to work with consummately professional actors, directors and producers who understood what I was trying to do. Even more, it was a legitimacy that had so far escaped my career: I was on my way to the writer's "A" list, where the Spielbergs and the Lucases played light-saber tag with adventuresome archaeologists.

You already know where this is going, don't you?

Davis did take the script to Fox. Before the studio would commit to a production deal (read as: before they would pay me one bloody cent), the exec from Fox wanted changes. Ridiculous, arbitrary changes. Changes as silly as the worst episodes of "Star Trek."

Maybe "Arachnid" was never great art, but it did sustain a certain internal logic and delivered on the suspense in every scene. I knew to keep the spider hidden for the majority of the film; keep people wanting to see what's behind that bush, how the spider will kill its victim. I only showed its legs, fangs, hairy armpits until it was time for the big payoff. I've been reading, watching and studying sci-fi horror for decades; I love writing it. The suggestions (demands) they piled on me wouldn't have passed my 11-year-old niece's bullshit alarm.

I struggled for a futile month on synopsis rewrites, all for free, hopelessly trying to find the focus of these ludicrous ideas. The result was reams of vacuous crap that pleased neither me nor anyone at the studio.

I was stunned. Where were the creative minds that propelled this movie business? Is the payday the only difference between the idiots at the bottom and the idiots at the top? "What did you expect?" my Cinetel friend Catalaine asked me. And maybe I wasn't a very good writer.

In the end they (Davis Productions, Fox Studios) wouldn't return my phone calls, and all the remaining steam seemed to go out of my agent regarding my once-hot/now-not career. It took longer and longer for David to return my calls.

I never heard from him again on a Sunday.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

EPILOGUE

I call it ESP, Endless Self Promotion. You learn that no matter who you talk to, or about what subject, you always mention: 1) Your latest project; 2) Your last project; 3) Five ideas for your next project; 4) All of the above -- twice.

Two years after Fox, having used my ESP, "Arachnid" ended up in the hands of an independent producer who needed scripts. Brian Yuzna ("Re-Animator," "The Dentist") had a three-picture deal with a Spanish film company that wanted to break into the American horror market. He pitched "Arachnid" as one of the 50 scripts that he could get. Those Spanish boys loved it. How can you go wrong with a giant alien spider? Then they read the script and loved it more. We began negotiating. Suddenly they didn't love it as much. In the end, they screwed me and I thanked them for it. I mean, who else is going to give me $45,000 for anything besides one of my kidneys?

I was actually happy at this turn of events. Even if "Arachnid" wasn't going to a studio, it was going to a group of people who had some low-budget chops. The producers, Sheri Bryant and Yuzna, are well known and well thought of in the horror world -- the director they hired, Jack Shoulder, equally so. The company that would do the spider effects and mockups, Steve Johnson's XFX, is one of the best in the world. Had I somehow slipped out of Fox, into a bucket of shit and come out smelling, well, if not like a rose then perhaps like one of those pine tree things you hang on your car mirror?

As of this writing "Arachnid" is well into post-production, which means it has been filmed and it is in the editing room being cut together. Is it, will it be, any good? Last I heard, the actors, competent professionals who no one was screwing on the side, did a good job. The Spanish film company had even at one point grudgingly approved some extra money. The spider puppets and animatronics had performed as promised.

All good signs.

Unfortunately, one of the producers has also recently informed me that the director is missing shots. This happens occasionally in the mad rush of a low-budget shoot, and most times it's nothing to panic about -- unless the missing scenes happen in the climax of the film and they feature (or don't feature, actually) the star of the movie, the king-size spider.

I don't know if the producers are willing to invest the money to fix the problem or if it's even possible at this late stage -- all the sets were struck. Maybe spooky hand shadows will take the place of the alien arachnid in the missing scenes.

"Did you see that giant fucking spider?"

"Where?"

"Right there!"

Shares