Thirty-seven years ago, late producer Walter Shenson told the New York Times that the Beatles never wanted to appear in a "rags to riches" story or, he went on, "the one about the record being smuggled into the studio in the last reel and put on by mistake."

Instead, he, director Richard Lester and screenwriter Alun Owen keyed themselves into the team's joyous group vibrations and produced "A Hard Day's Night." In it, we see the Beatles establish an unmatched rapport with their audience. Their young female fans catch fire from their pop sensuality, and their young male fans soak up confidence from the group's freewheeling exuberance.

And, apparently, still do. In the opening weekend of its current rerelease, "A Hard Day's Night" grossed a jaw-dropping $50,000 in two theaters, one in New York and one in Los Angeles. Miramax president Mark Gill told me Monday, "We got astonishingly high audience surveys -- second only to the ones we got for 'Good Will Hunting.' It doesn't mean that we'll get as big an audience as we got for 'Good Will Hunting,' but it does mean that the people who come into the theater will walk out the door and tell other people that they love it. It's encouraging that not all of them identify themselves as Beatles fans. We're also getting nonfans, or people who are not yet fans, and they love the movie too."

Gill says a lot of blind luck went into the timing of this rerelease. Shenson, who owned the copyright, originally shopped for a new distributor amid the euphoria surrounding the Beatles' 1995 "Anthology" TV and CD series. I talked to Shenson, who died in October at age 81, and the film's restoration honcho, Paul Rutan Jr., when the film began to weave its way around the festival circuit in 1998.

But Miramax wanted to wait for Shenson's foreign and video deals to lapse so it could acquire clean distribution rights. By the time that happened, says Gill, he could see both the new "Anthology" book and "1," the Beatles' hit singles album, on the horizon and decided, last July, to delay the movie's rerelease until now.

In a way, it's ironic that Gill is giving the movie the sort of sophisticated platform that's usually reserved for art-house classics. (It will hit the top 10 markets Friday.) In the fall of 1963, when United Artists approached Shenson about making a movie with the mop tops who were sweeping the United Kingdom and the Continent, UA was thinking exploitation. The company never expected a Beatles vehicle to play in more theaters simultaneously than any other film of its time, or to win terrific reviews, or to return a blockbuster $13.5 million on a $560,000 investment.

The group had yet to cross the Atlantic. By the time the Beatles did explode in the United States, Shenson had already signed them to make a low-budget, black-and-white film. United Artists thought the movie would be little more than a promotional tool for the soundtrack album, but Shenson guessed better and with uncanny foresight cut a deal that would return the copyright to him after 15 years.

The film has since been a perennial attention getter. Ever the showman, Shenson kept trying to bring the Beatles' audience something extra whenever he rereleased the film. He opened the 1982 version with "I'll Cry Instead," a song recorded for the movie but not used, and played it out against a montage of production stills; he attached "You Can't Do That," a visually muddy number that had been deleted from the TV-concert sequence, to the end of the print that roamed the festival circuit two years ago.

I prefer the current-release prints, which give us the original pop masterpiece straight, no chaser. In the following interviews, restorer Rutan explains how he got the film back to where it once belonged, and Shenson recalls how he got it made right in the first place.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

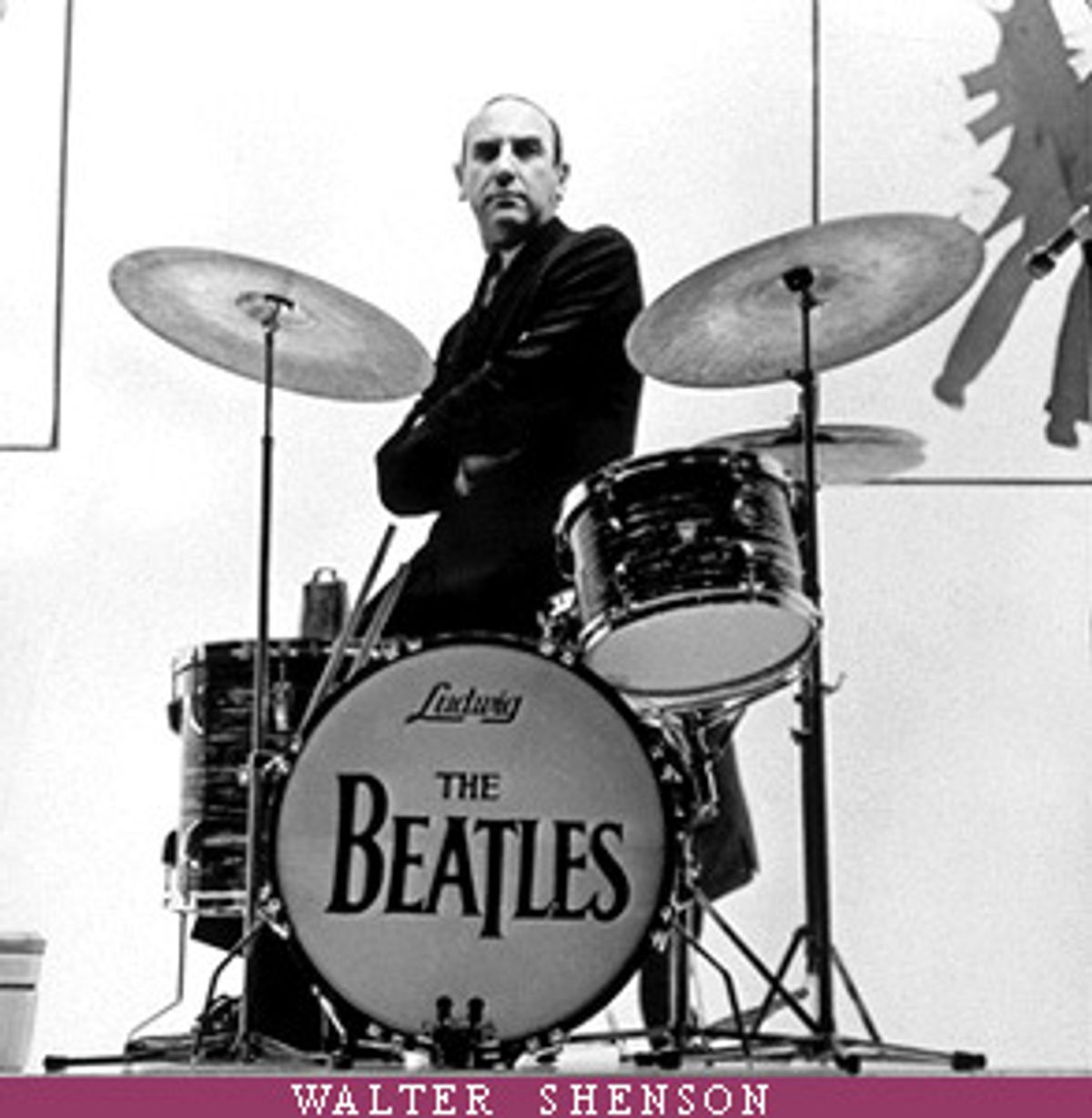

In the midst of the frenzy surrounding the filming of "A Hard Day's Night," a reporter on the set described Shenson as "miraculously relaxed." That's how I found him the three times I interviewed him, most recently at his Beverly Hills, Calif., office in March 1998.

To Shenson, who moved to England in the mid-'50s to coordinate advertising and publicity for Columbia Pictures in Europe, the story of "A Hard Day's Night" began when he produced the hit screwball satire of American foreign relations, "The Mouse That Roared."

"I fought to get Peter Sellers into 'The Mouse That Roared,'" he recalled, "and it became his greatest success up to that time. When I was preparing the sequel, 'The Mouse on the Moon,' Peter had already gotten too big for me to use. But he asked, 'Is there anything I can do for you? Do you need a director? What about Dick Lester?' Lester had directed Sellers on TV and I set up a screening of a quickie musical he'd made ['It's Trad, Dad'].

"I could see he knew how to cut a film and make it move. Dick directed 'The Mouse on the Moon'; the year it came out UA asked me to produce the Beatles film. When I told Dick about it, he got very excited -- he knew more about the Beatles than I did. He said, 'I'll do it for nothing.' I said, 'We'll all do it for nothing -- it's a very low-budget film.'"

Were you ever tempted to bring Peter Sellers and the Beatles together?

No, by then Peter Sellers was doing "Pink Panther" things, big Hollywood pictures.

Was the first movie you and Lester made together, "The Mouse on the Moon," a success?

United Artists was pleased enough with it to ask me if I would make a film with the Beatles. I had been living in London for about seven or eight years, working for Columbia Pictures and making independent comedies. I knew who the Beatles were, even though they had not yet come to America. I said, "You mean you want to make a movie with those kids with the long hair? What do you want to do that for?"

They gave a very reasonable reason. United Artists records would get the album, and it was worth financing a low-budget film in order to land the Beatles' soundtrack. I thought that would be good. So they put me together with Brian Epstein, the Beatles' manager, and apparently he thought I was OK because he then introduced me to the Beatles. John Lennon was their spokesman, in a sense, although I spoke to all four of them at the same time. The first thing John asked me was what kind of film I wanted to make. I said, "Well, a comedy." They all looked at each other, then said, "Well, OK, you can be the producer." Two of them were 21 and two of them were 23; they were pretty young.

They asked about a director, and I had recently had lunch with Dick Lester. He was back doing commercials and wanted to know how our film had gone with United Artists. I said it must have gone all right because they asked me to produce the film with the Beatles. He just jumped up from the table and asked, "Can I direct it?" That's how it all started. When John Lennon asked me if I had a director in mind, I said, "Yes, he's another American; he lives here in London, and I think you probably know his work because he directs the television series called 'The Goon Show.'"

Well, "goons" was the magic word. Young people all over Britain were watching "The Goon Show" on television with Peter Sellers and Spike Milligan and some very talented comedians. I thought it was the Beatles' kind of humor. They looked at each other as if to say, Oh, if Dick Lester directs "The Goon Show," we'll get him, you know?

Things fell into place. This meeting was in November or December [1963]. I asked them what they had coming up in their diary, and they said they were going to the Bahamas for a holiday. Then they said in February they were going to go to my country and do something called "The Ed Sullivan Show." When they came back they'd be free to do a film. I said, "By that time we'll have a writer assigned and we'll have a script; in the meantime, while you're in the Bahamas, write a bunch of new songs for the film." I mean, that's what a producer's supposed to do, you see?

They looked at me and asked, "What's the film about?" And I said, "We haven't got a writer yet, so I don't know." But I told them to write Beatles songs: two up-tempo, two ballads, whatever they wanted. I was kind of hoping the title of one of the songs would work for the title of the movie. So they went down and wrote those songs while we were working with Alun Owen on the script. Then they came back and they went into the recording studio with their record producer -- ah, you know who I'm talking about.

George Martin?

George Martin. They recorded everything. We still didn't have a title song for the film, but we figured we'd get something. Then they went off to America, and the people from United Artists in New York, who had really left me alone completely up to that point, called me on the Monday after the Sunday the Beatles were on "The Ed Sullivan Show." They were so excited. They said, "Walter, 70 million Americans have just seen the Beatles. Do you need any more money? What can we do to get you going?" And I replied, "Everything's on schedule, don't worry about it. We're right into it; we'll give you a good picture." And we did.

The story goes that you and Dick Lester, when you were with the Beatles, saw the chaos that was surrounding them and how crazy their life had suddenly become. Seeing that and being with them inspired you to give the film the shape that it had, as a day in the life.

I wanted them to meet Dick Lester when they were rehearsing a radio show. We strolled down to the theater where they were rehearsing and between rehearsals we had tea with them and chatted. They got to like Dick and off we went. I'd say he was still in his 20s, Dick was, so he was closer to their age than I. It was good -- I was sort of Uncle Walter at that time.

But what really mattered was that Dick and I came up with the idea of Owen to do the screenplay -- not because he was available and had done a play and some television but because he was from Liverpool and it seemed natural that he could write in the Beatles' idiom. When we assigned him the picture, he wanted to know what we wanted him to write. We said, "An exaggerated day in the life of the Beatles." And he asked, "What's that?" I said, "Well, they're going to be performing in Dublin next weekend; I'll arrange for you to go up there and move in with them. When you come back, you tell us what it's like to be with them."

And he did. He came back and was astute. He said the Beatles get off the plane to go to the hotel; they go to the concert hall; they get back on the plane. They don't know whether they're in Dublin or San Francisco. They were literally prisoners of their success. And they would travel in a cocoon of Liverpool. There would be the manager, the road manager, the publicity man, the guy who carries the equipment -- all chums from home. The Beatles didn't know where they were half the time: That was the essence of Owen's screenplay. Owen got an Oscar nomination, and my feeling is that he should have won. Of course, I'm biased.

Did you see something essentially comic about the Beatles from the start?

They played themselves, and I think Alun Owen's script was brilliant because he tailored it to them. We did learn a lot as we were shooting because we didn't know them as individuals. We knew that John was the quick one. We knew that Paul was the good-looking one. We knew Ringo was going to be the butt of the jokes -- for whatever reason, it was obvious. We didn't know much about George Harrison. So we had Alun Owen around all the time, and as we were going along and looking at the rushes each day, Dick and I were saying, "You know, George is really interesting. Let's get another scene for him." So we called Alun in and he wrote two or three scenes that George played wonderfully well. George was playing George, and he was comfortable doing it. I think one of the reasons the picture was so successful and still is popular is that we captured the Beatles.

The other thing, of course, was the genius of Dick Lester, who once said that he got a plaque or some certificate for being the father of rock videos. No question about it -- here it is 35 years later, and I still think the stuff he did in "Help" is absolutely brilliant, and the stuff in "A Hard Day's Night" too. He knew how to photograph and direct a song. Whenever I see the film I'm amazed at how entertainingly the songs are performed. Let's face it, in movies some very, very good singers, like Frank Sinatra or Bing Crosby, simply stood up there and sang. And that was OK for them because they also could act.

So you're saying that because the Beatles were totally untrained as actors, you had to create a context in which their personalities could emerge -- you couldn't just show them standing up and singing?

Absolutely. And as I said, this doesn't happen by chance. We were very fortunate that Alun Owen was the kind of writer who could do it. He knew the Liverpool lingo and the idioms, so they weren't faked, they weren't phony.

He also invented new ones.

He made it easy for the Beatles; they were at ease with his dialogue. And then Dick had a little streak of surrealism. Every once in a while he'd do something that was ridiculous, surrealistic, but always in the tone of the film. Like, in the beginning of the film, you see them sitting on the train and the next thing they're running alongside the train; or John is in the bathtub and in the next cut he's not in the bathtub and he comes in and says, "What are you waiting for? Let's go!" For humor, you know. Nobody expected this film to be a documentary. You didn't have to stay logical all the way through. The point of view was to entertain.

Did Dick Lester ever make you nervous because he was inventing so much as he went along?

No, no. I kept hugging him every day when I saw the rushes. I said, "Dick, it's great, it's great!" There's one good example. There's a song, "And I Love Her," that Paul sings as a solo and Dick covered it with lots and lots of footage, a lot of angles. And one idea that he had was to put the camera operator in a little swing chair that hung from the ceiling of the soundstage and then have one of the crew guys follow Paul's movements around and stay tight on him. We must have had almost a 360-degree version of the shot, going right off the set. Then we had the normal coverage you have, so that when the film was put together it was beautiful to look at while you were listening to this good song. I did get a phone call, when we sent the finished picture to United Artists, from one of the executives, saying, "Oh, are you aware of the fact that in one scene where Paul McCartney is doing a solo, the camera shows the walls of the soundstage?" I said, "Yeah, it took us a half a day to get." So of course I had dead air on the other end of the phone. You know, for a lot of people it's very difficult to accept change and to accept that things are going to work that haven't been done before.

Another executive said, "The picture is great; we love it. Thank you very much. We're getting it out. But are the Beatles going to last?" I said, "I have no idea, why do you want to know that?" He said, "Well, do we make a lot of prints and cash in on their popularity now?" I said, "You're the distributor; they are popular now. Do what you think is right. I can't tell you whether they're going to last or not. But you'll like this film."

Nothing was conventional about this thing. And I think that's why it was so popular when it came out, and it was 35 years ago and it still plays. Nothing has dated. I played this film for film students fairly recently and when I finished I asked, "How many of you have seen the film before?" Maybe half a dozen hands go up out of an audience of 100. They'd never seen the picture before and they were flipping over it. I asked, "Did it seem dated in any way to you?" And the students would say, "Not dated, just British."

- - - - - - - - - - - -

Paul Rutan Jr. has been making films look their best for more than a quarter-century -- as he puts it, "long before there was such a thing called restoration." In 1974, when he started working in the film business for his dad, he specialized in taking obsolete big-screen formats like Techniscope and converting them for television. "We would deliver 16 mm prints to all the little TV stations and 35 mm to the networks," he recalls. Today he runs a restoration center dubbed Triage.

Few cases are weirder than the restoration history of "A Hard Day's Night," which began with a search for decent prints of the second Beatles film, "Help!" (another Shenson-Lester production). I interviewed Rutan at Triage in Los Angeles, around the same time as my interview with Shenson.

What got the ball rolling for the restoration of "A Hard Day's Night"?

It began early in the '90s. I'd worked with Bob Harris and Jim Katz on their restoration of "Spartacus," and I did some work with them on "My Fair Lady." Walter Shenson contacted me because he knew Jim Katz. He'd gone to Jim to ask him for advice on how to get a print of "Help!" out. Walter didn't have the money to hire Harris and Katz to do the job.

Walter needed an element of "Help!" he could use for telecine purposes [the telecine is the machine that transfers movies to video] and, a year later, for a six-theater release in Germany. I think "Help!" is more popular in Germany. I don't know why -- maybe because guys wear lederhosen in some of it. I started out with a lot of Eastmancolor prints that were wrecked. Then I found out that the original negative had tears and rips and horrible scratches in it. But I located an old German dupe negative, and from that I made a low-contrast print. I used sections of that for fixes. It didn't have the physical damage in it that the original negative did.

Later, Walter called me up and said, "Paul, I have this other picture, perhaps you've heard of it. It's called 'A Hard Day's Night.'" I said, "OK, I'm ready." I basically worked the same way on that. He needed an element to make a telecine transfer of the movie. He sent all his black-and-white prints of the film, which were flat, just terrible. He sent prints from the 1982 rerelease, which were on color stock and were no good. To top it off, two reels of the original negative of "A Hard Day's Night" were missing. I found only bits and pieces of the originals of those reels; I think people took those reels for clips and cut them right out.

For those reels, I had to go through the material I had and, frame by frame, pick out chunks of dirt embedded in the emulsion with a blunt pair of scissors. In a lot of areas the only thing I could do was turn the white dirt black because black is less objectionable. In other words, I would have to pick out that dirt all the way through to where it was a hole in the emulsion. But I did create a new dupe negative for those missing reels.

Was Walter working on a budget when he had you do this? Had he made a big distribution deal with anyone?

The money came out of his own pocket. I consider him to be something of a pioneer. If you're a big studio and you've got the cash, you can afford to fix a show -- and even the big studios balk at fixing a show that they don't really have a market for. Walter was hesitant to spend the money, but he loved the picture so much that he did.

What allowed me to finish this job is another story. We belong to this group called the Association of Moving Image Archivists. I had done about 60 to 70 percent of "A Hard Day's Night" when I met a woman named Carolyn Frick from American Movie Classics. You know, they show the "soundies" on AMC that feature the old swing bands. She thought they could do something special with the Beatles. I gave her Walter's name. The next thing I know he's calling me and saying he sold these shows to AMC, and as a result I was able to supervise the telecine transfer for AMC.

We had already completely fixed the original negative. It was done and it was beautiful. And we had struck prints. But we had yet to make an element for archiving. The AMC sale enabled us to make the fine-grain master and then supervise the telecine transfer. We moved like snails, but we did it.

I'll be honest with you: Miramax took this show even further. I didn't have a duplicate negative for making new prints. When Miramax called and asked, "Well, what do you have?" I said, "Nothing." "What do you mean, nothing?" "I mean nothing. Every time we print we have to go through the original negative and then mend it, because it's 35 years old."

Now [after Miramax agreed to pay for it] there's a protection duplicate negative that the release prints are going to be struck off of. It's really good -- and the sound is spectacular.

The sound was a problem for me with that movie the last couple of times I saw it.

We owe the new sound to Ron Furmanek. He's a Beatles archivist who's done a lot of work with Capitol Records and EMI. Originally, all the sound I had for "A Hard Day's Night" was shit. Walter, as he probably told you, was making this film when the Beatles were on "Ed Sullivan." After the Beatles knocked 'em dead, the executives at United Artists grew concerned about having all this screaming in the movie theaters that would prevent audiences from hearing the soundtrack. Walter pooh-poohed it, but when UA did the soundtrack for the American version, they overmodulated it. They turned it way up. And as a result, entire areas of sound got clipped. Right where you would see peaks on the track, it got cut out.

On the simulated Dolby stereo track for the 1982 rerelease, they struggled to compensate for that. And it didn't sound very good. I sent Ron what I had -- fine-grain masters from 1963, two or three different original soundtrack negatives and dupes -- and he went, "I can't use this stuff." But he also said, "I have a black-and-white print that I've had for 30 years." It was British, and it didn't have that problem. So he worked off his own print and it sounded fine.

In fact, it sounds better than it ever has in this country. The sound guys ran it through all the whistles and bells of cleanup stuff. But the real thing was, they separated it: Now it's in six-channel digital. I was concerned about it because the track is mono. Well, it's just magnificent -- nothing's fake. You can hear every word they're saying, even with the English accents, and the music is phenomenal.

Shares