In François Truffaut's "Mississippi Mermaid" (an ideal Christmas film, ending in snow-filled scenes where you're drained of trust), Jean-Paul Belmondo lives alone on the island of Reunion in the Indian Ocean. He owns a cigarette factory and a mansion, but there's no attempt to explain why the rich, handsome man is solitary. He arranges for a mail-order bride, and she travels on a slow ship. He's there on the quay, with a photograph sent by the young woman, but the one who arrives looks not like the woman in the picture but exactly like Catherine Deneuve.

Still, he accepts the inconsistency. Wouldn't you? If you wouldn't -- and of course you shouldn't -- this film is not for you. But if you would, then there's likely some flaw in you, like not having a companion already on Reunion.

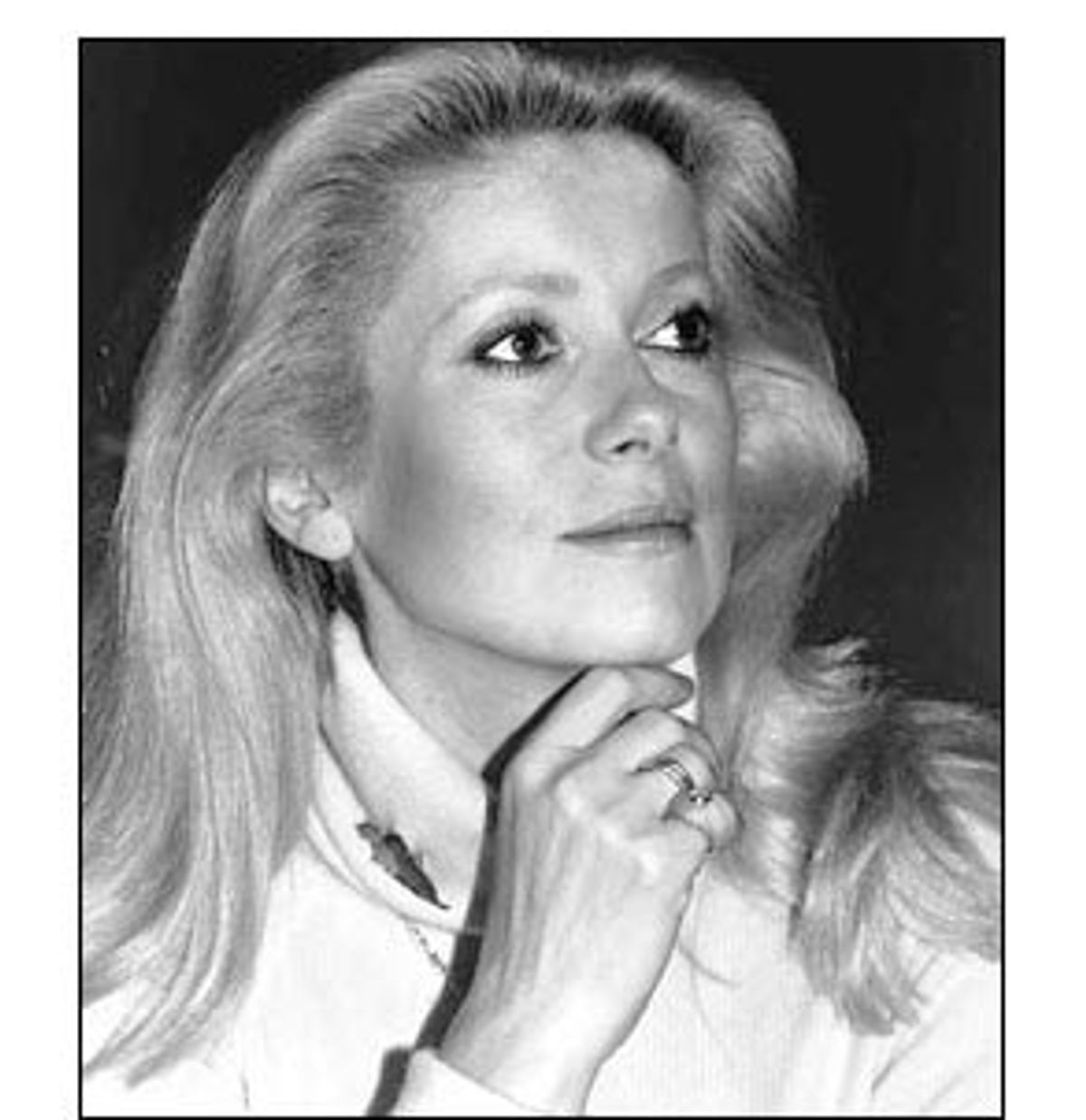

Deneuve is dressed by Yves Saint Laurent, yet is undressed a lot of the time too -- often enough by her own absentminded fondling. We know she's a liar and an impostor, so dark at her blond edges, so loaded with some fatal design. It's not simply that Belmondo falls in love with her; he falls in love with the sinister prospect she opens up, for she is right in all the wrong ways.

She robs him and escapes back to Europe. He follows her (his other life is gone, or occupied by her), and by weird chance sees her as a passerby on television. So he tracks her to Antibes, where she is a performer in a rough club, dancing with sailors and loving it. Belmondo, watching her from the shadows, realizes that this whore could never have loved him.

He closes in on her in her room, an elaborately painted chamber with a life-size mirror. And here it is that Deneuve does one of her great scenes, prowling around, finding the mirror, using it as a prop in acting and as a model for lying and explaining why she robbed him, why all of the money is gone and why she really does love him. He believes her. You would, if you'd seen the scene and had its yards of fragrance spun around you.

There's much more to come in this dreamy waltz into darkness. There are killings ahead, and the possibility of poison. But after that explanation scene -- which is a seduction without touch -- Deneuve's crazed yet aimless force takes over the film. She lifts Belmondo and carries him with her until we see the strange way in which the two outsiders (natural liars and helpless rebels against order) are so suited to each other.

Deneuve has often made herself extra erotic by seeming demure or restrained. She's different here. Her blond hair has streaks of earth and rusted iron in it. She often touches herself in little autoerotic ways. And she takes her shirt off like a child at the beach. Truffaut was drawn to this idea of a woman as life and death force at the same time -- that's how Jeanne Moreau commanded "Jules et Jim." But "Mississippi Mermaid" is a richer, more haunting film, with its own reckless notion of love and loneliness. It's what you might be doing if you weren't having a happy, standard, familial American Christmas. Did anyone hear a scream?

Shares