Bucky Sanders' casket store in Hot Springs, Ark., sits near a railroad track and, appropriately enough, two cemeteries. His small shop looks more like a used auto parts store than a place where bereaved families go, but Sanders isn't trying to affect the somber formality of a funeral home. All he's selling are coffins.

Sanders has a clear and simple mission: to sell caskets cheap. He'll sell you a coffin with cherubs on the corners and the Lord's Supper on its handles for $1,800. That's half what a funeral home charges, and if you can't pay for it outright, that's fine with Sanders, who worked for 43 years at a local funeral home.

"Funeral homes demand the money on the spot," says Sanders in his Southern drawl. "A lot of people just don't have the money. I try to work with them. I think this would be pleasing to the good Lord."

Sanders buys his caskets from a company in Houston. At any one time, he has 12 to 15 of them in stock with price tags that range from $950 to $2,000, including free delivery to anywhere in Arkansas. Business is good, but pressure from funeral companies is a constant thorn in his side. It's not uncommon for Sanders to get an anxious call from a customer whose funeral home has refused to use a casket from Sanders' store. What the home is doing is against the law, Sanders tells the customer, and, in Arkansas at least, he's right.

Twenty years ago, the only way to get a casket or cremation urn was through a funeral home. Without competition, funeral directors marked up caskets as much as 700 percent, including in that lump sum the costs of the hearse, embalming, the wake and other items.

In 1984, the Federal Trade Commission forced change on the industry, requiring, among other things, that funeral homes itemize their charges. This aspect of the new regulations turned out to be a boon for funeral home directors: Instead of including multiple services in the single casket fee, businesses simply left the inflated casket prices as they were and tacked on additional charges. Subsequently, funeral costs grew 5 to 7 percent a year.

The 1984 rules also required that casket prices, manufacturers' names and model numbers be made available, and allowed independent casket dealers to get in on the market by supplying caskets directly to consumers. But in many parts of the country, that legislation remained toothless as long as states were permitted to limit the sales.

As family-owned funeral homes, once a staple of small-town life, give way to large corporations like Service Corporation International (whose allegedly unsavory dealings with Gov. George W. Bush were reported in Salon), Americans are pursuing other methods of dealing with their dead. Thanks in part to Jessica Mitford's landmark 1963 book "The American Way of Death" and its 1998 sequel, they're growing savvier to the ways of the funeral industry and challenging long-established practices.

While independent casket dealers move in on a long-protected market, families are building or designing their own caskets; they're cremating the deceased in growing numbers and burying people in "eco-burial" grounds. Baby boomers are planning their funerals as they do their lifestyles with alternative and creative choices -- designer caskets, homemade cremation urns and funky funeral services with rock 'n' roll replacing traditional religious hymns.

And as Sanders and other independent dealers fight for the right to sell their caskets to anyone who wants them, the last vestiges of the funeral industry's monopoly on the way we die are slowly being wiped away.

"I get sick of seeing people being ripped off," says Rick Dancy of Meridian, Miss., who recently earned the distinction of being the first man in the United States to be imprisoned for selling caskets from an independent dealership. A court later found the arrest unconstitutional, and Dancy continues to sell the caskets that he buys from Casket Royale, a New Hampshire wholesaler that has dealers in 44 states.

"There's no sense in people having to pay double for a casket just so the funeral homes can make a good profit. A casket store puts the power back to the people," Dancy says.

In effect, Dancy, Sanders and other independent casket dealers are reversing the consolidation of the funeral industry that took place over the past century or so.

The tradition of the funeral home dates back to the Civil War, when soldiers' bodies were embalmed before undergoing the long transport back home to their families. Initially, this task belonged to the coffin maker, often a local furniture dealer who took on the job of preparing a body for burial. As Americans began to cluster in urban centers and move into smaller apartments, it became necessary to find surrogate "homes" in which to hold wakes. Thus funeral homes were established, soon becoming single-stop outlets for funeral services -- embalming, viewing, hearse, flowers, casket.

For much of the century, the funeral industry faced little competition. The death of a lover or family member proved enough of a preoccupation to keep families from shopping around or demanding alternatives to the options funeral homes gave them. Even today funeral homes exploit families' grief to extract high fees. According to Lisa Carlson, president of Funeral and Memorial Societies of America, the cheapest casket on the market is a $150 cloth-covered particleboard box that many funeral homes resell in the $695-$895 range. Funeral directors, when telling families about their options, commonly call this the "welfare box," effectively shaming families into buying a pricier model.

Over the past few years states have slowly opened up the market to independent casket dealers. Today, only six states -- Louisiana, Alabama, Idaho, Oklahoma, South Carolina and Virginia -- prohibit casket sales by independent dealers.

In November, Mississippi was crossed off that list when a federal judge struck down the law that had allowed casket sales only by licensed funeral directors. The state had argued that its law addressed health concerns because human remains need to be buried quickly. But the judge rejected that claim, saying he was skeptical that "possible ignorance or incompetence of an unlicensed dealer would delay burial, as such a dealer is selling what amounts to be a glorified box."

The casket war has also hit South Carolina, where a judge recently struck down the requirement that casket dealers have embalming rooms, chapels and hearses. To sell caskets, however, a person must still be a licensed funeral director. And in August, a federal judge ruled that Tennessee's funeral director law violated the 14th Amendment's protection from arbitrary regulation.

A federal court also recently tossed out a Georgia law prohibiting casket sales by any entity other than a funeral home, calling the law a blatant restraint of trade. In a desperate attempt to keep its regulations alive, the state argued that allowing independent casket dealers to engage in a price war would "promote the criminal element" -- in other words, that the easy availability of caskets would encourage murder.

The country's traditional coffin makers -- Batesville Casket Co. and Aurora Casket Co., both of Indiana -- still sell wholesale only to licensed funeral directors. Casket Royale has grown to be the world's largest provider of caskets to third-party funeral merchandisers -- and is a major force behind moves to open up independent casket sales in the South. The company currently services independently owned and operated retail funeral stores; it also sells directly to the public.

"We sell at least one a day to consumers," said Mark Ginsberg, president of Casket Royale, which likes to tout itself as the Wal-Mart of the funeral industry. "We advertise on TV about 60 times a day. People are tired of being dictated to by the funeral industry."

These days, more bereaved families are becoming savvy about funeral services -- saving hundreds, sometimes thousands, of dollars when they shop to compare prices.

The National Funeral Directors Association reports that the average amount spent in 1999 for a funeral was $5,778.16, with $2,176.46 of that going toward the casket and $1,000 for cemetery charges. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics' consumer expenditure survey, funeral spending is on the decline, dropping an average of 7 percent annually since the mid-1980s. Some industry experts say the high cost of dying is why cremation is on the rise nationwide, even in the South, where traditional burial is usually preferred.

The development of an independent casket industry is part of a larger movement of families playing a bigger role in their loved ones' deaths.

"This is the same generation that reinvented natural birth in the delivery room," says Carlson of Funeral and Memorial Societies of America. "I think we will see more boomers changing the way funerals are handled and see more people having at-home funerals."

As Arnold Goodman, a Minnesota rabbi, wrote in his 1970s book "A Plain Pine Box," the practice of surrendering our dead to funeral homes has taken us far from the intimate experience of death that was once a part of living. "Customs of the past, which required families to wash and prepare their dead ones for burial or cremation, for the construction of the casket and shroud, the choice of which families and friends would assume responsibility for preparing the dead for burial, for making arrangements with -- and for -- the family for fabricating coffins and burial garments, have all but disappeared."

When Stacy Black and Jeff Esley's father was diagnosed with terminal cancer, they decided that his funeral should be in keeping with the way he lived life, and not take place in the decorous anonymity of a funeral home.

Esley, who is a master woodworker, built his father a casket modeled after one he'd seen in the old western movies his father loved. Black made the satin lining for the casket; an aunt made the pillow. It was a way of keeping their father's death in the family. Black says, "It was something truly from the heart." Since then, Esley has received calls about making caskets for other people.

New traditions are arising all across the country. Ramsey Creek Reserve offers burial sites for biodegradable caskets, and forbids gravestones or plastic flowers in a burial that costs about half the cost of a traditional funeral home burial. The Funeral Consumers Alliance directs visitors to organizations that supply all the components of a make-it-yourself casket.

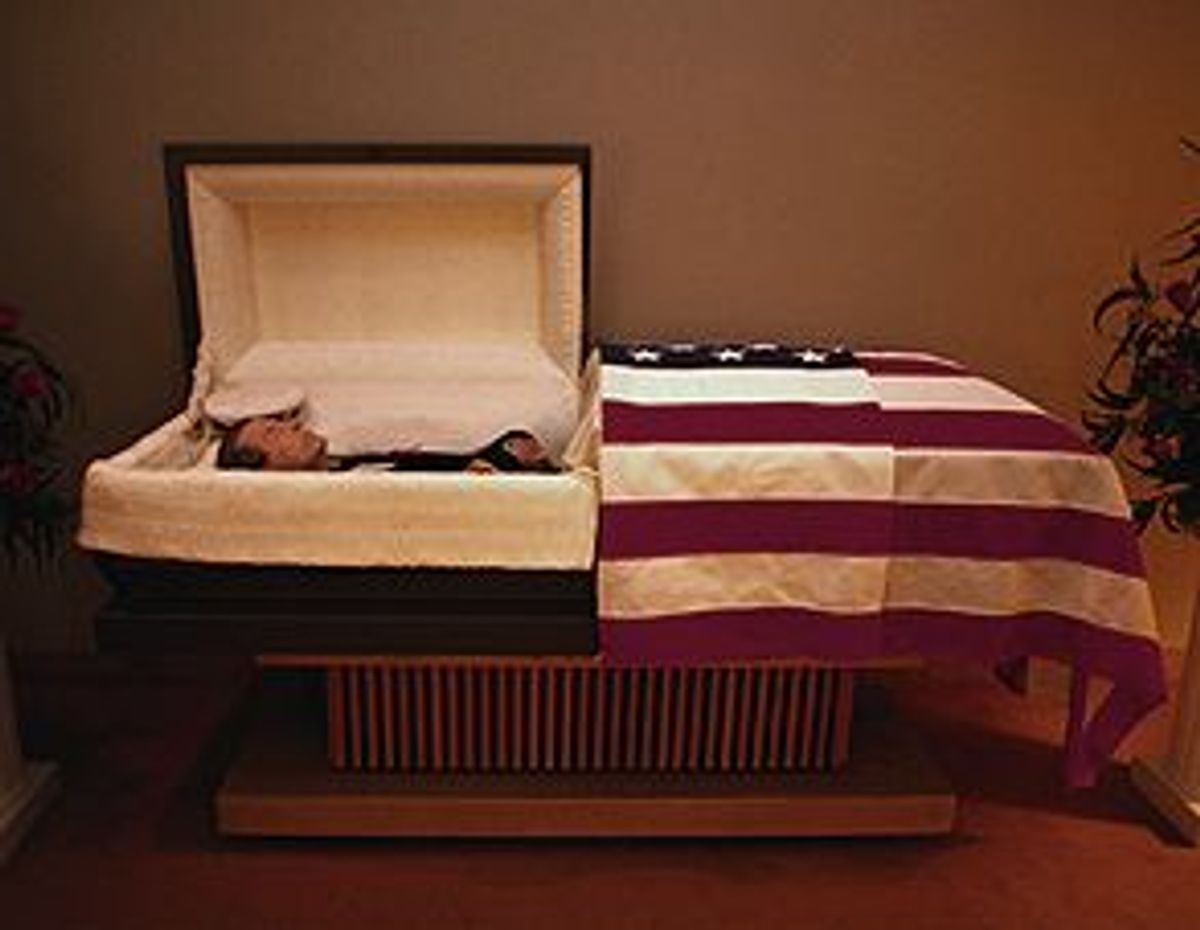

Or, for those for whom "individualizing" death means expression, not austerity or environmentalism, there's Whitelight Casket Co. in Texas. Whitelight has created "Art Caskets" that feature religious and ethnic themes, scenic landscapes, vocational and lifestyle images and symbols of patriotic pride and nationality. Designs include a rosary, breast cancer and AIDS awareness ribbons, an ocean beach, New York, the flag of Ireland, Our Lady of Guadalupe, clouds, the Last Supper and a lighthouse.

Sanders says that the movement toward independent casket dealerships is just a matter of fairness. He says that in his years in the funeral business, he saw too many families struggle to try to buy their beloved a decent funeral. When he retired, he wanted to do something to counter the industry that had fed his family for many years.

"People should have a choice," he says. "I don't know how funeral home directors sleep at night knowing they are ripping off people the way they are."

Shares