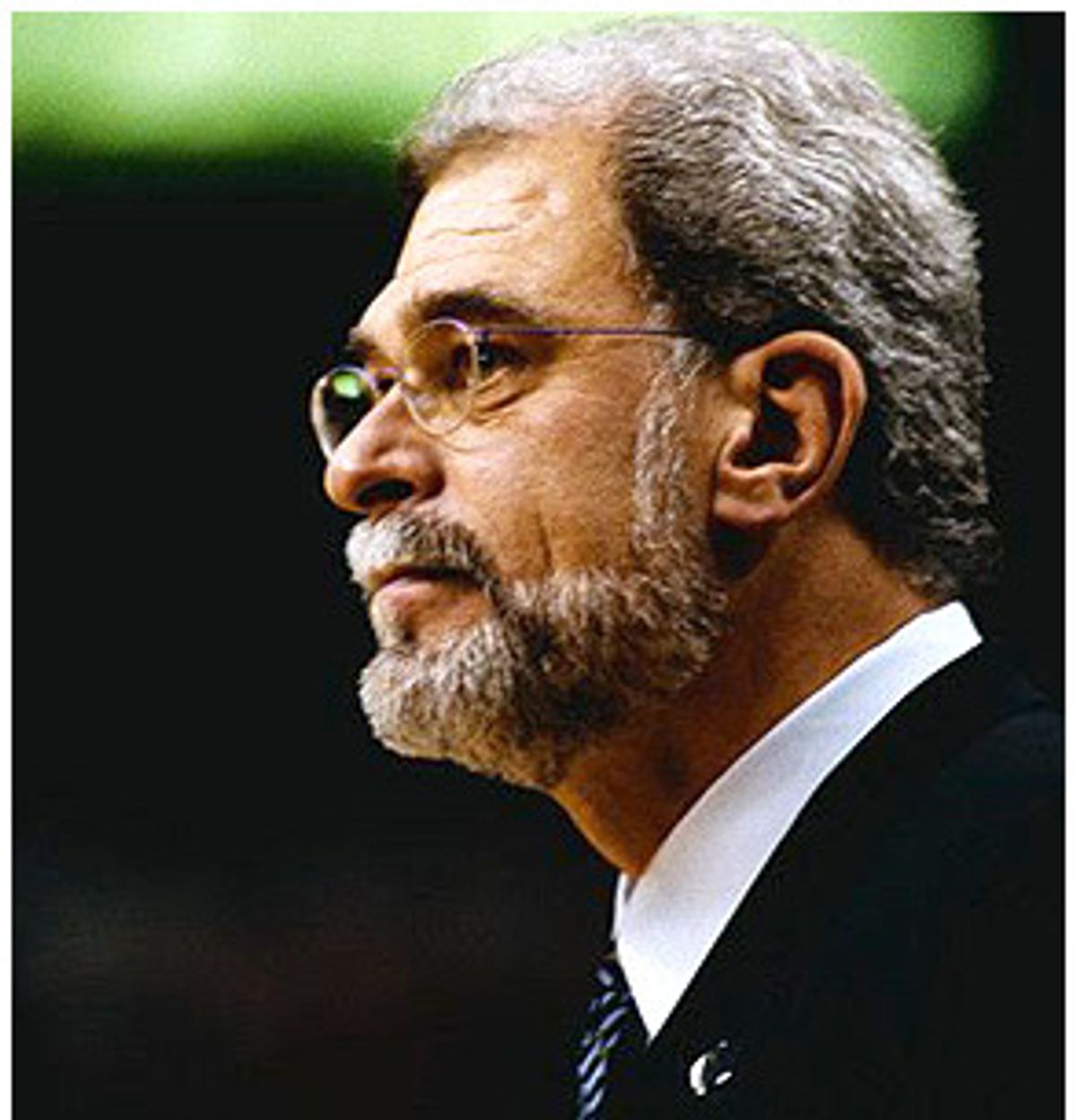

I'm sure there have been many moments. But the one I'm thinking of happened late in a meaningless regular season game against the muddiest of doormats, the 1998 edition of the Dallas Mavericks. Phil Jackson's mighty Bulls were mailing it in -- imitating basketball in a game they would eventually lose. It was then that he entered what can only be called a State of Phil. Rather than resort to the usual motivational exhortations of superego figures, Jackson did something unprecedented in professional athletics: He started clipping his nails. When Jackson achieves Phil, he stands at a universal meeting point where parts become indistinguishable from their whole. He is at once in your face and removed, as if surveying multitudes of you across space and time. The art of Phil is such that even the losses seem by design.

But Jackson seldom loses. This year, Jackson will complete his 11th season as an NBA coach. He spent his first nine with the Chicago Bulls, where he garnered six championships. He took the 1998-99 season off, then returned to lead the Los Angeles Lakers to glory in 2000. If his Lakers go on to win this year, it will be Jackson's eighth championship. Only Red Auerbach has more with nine -- a record that Jackson may very well break if he decides to stick around that long. Jackson has achieved his success with a uniquely New Age approach: a blend of Eastern and Western ideas heretofore foreign to professional sports. He has been known to regale players with tales of the sacred white buffalo of the plains, coach them in meditation techniques and burn sage to reverse a losing streak.

Perhaps because of his bizarre methodology, Jackson is not without his critics. They point to the great players he has always had on his side -- first Michael Jordan and Scottie Pippen, and now Shaquille O'Neal and Kobe Bryant. It stands to reason, they argue, that Jackson wins -- the deck is always stacked in his favor. And they have a point. Jackson knows when to hold 'em and when to fold 'em. When the Bulls broke up, he walked away from the game until he found a sure bet with the Lakers.

But there is another side to the story. Jordan and Shaq played a combined 13 years without Jackson and never won a championship. Meanwhile Jackson has known success at every level -- first as a player with the 1970 and 1973 Knicks, then in the lowly Continental Basketball Association, where he won a title with the Albany Patroons.

The CBA is where Jackson earned his stripes. Not only did Jackson coach, he drove the van. Late at night he took his band of malcontents and might-have-beens from one basketball outpost to the next, each light-years away from the NBA and anybody who might care about their accomplishments.

While at Albany Jackson persuaded his team to divide salaries and playing time equally. Married guys got a $25-a-week bonus. This type of egalitarianism is without precedent in professional sports -- you find it on a few scattered T-ball teams. Generally speaking, these are the teams that sink to the bottom of the standings and a parent-inspired mutiny follows. Not so with Jackson's Patroons. In 1984, they took the CBA title.

And this is the magic of Phil. Somehow, he manages to be at once himself and whatever his players need him to be. In an era when everyone wants to be an emcee, in an environment where the limelight's wattage determines self-worth, Jackson opts for a lower profile. Winning or losing, on the bench his demeanor never strays. At times, it seems as though the game played before him simply distracts him from other, more important mental activities. Like the Wizard of Oz, his machinations remain hidden.

Born to Pentecostal missionaries in North Dakota, Phil Jackson learned the art of manipulation early in life. As a player, his mental grasp of the game far outstretched his physical capabilities. Jackson was oafish and often injured, and opponents feared his sharp elbows more than his sharp shot. Red Holzman, his coach on the New York Knickerbockers, barred him from dribbling the ball.

Nonetheless it was clear that Jackson was operating on levels foreign to the linear minds of professional athletes. Former Knicks teammate Walt Frazier recalls, "He could have been a better player if he had applied himself to it more, as much as he applied himself to his books. He read those weird books. They were weird to us anyway. No one else ever read them anyway."

Relating to players through books would later become one of the hallmarks of his unique approach to coaching. He has assigned "To Kill a Mockingbird" to Horace Grant and Nietzsche to Shaq.

And it was a book that nearly put the kibosh on Jackson's coaching career before it even began. In 1975 he wrote "Maverick," a memoir about his days playing in the NBA. Among other things, Jackson spoke frankly about marijuana use and experimentation with LSD. It was a critical success, but the book cemented a loose-cannon reputation that would alienate him from the NBA establishment for years.

It took another pariah, Bulls general manager Jerry Krause, to rescue Jackson from anonymity. Krause, widely disliked even then, had scouted him when Jackson was a Barry Goldwater supporter at the University of North Dakota. Decades later, Jackson was coaching in a Puerto Rican summer league, and had all but vanished from the basketball map. Krause persuaded then coach Doug Collins to bring Jackson in for an interview. The two liked each other and Jackson got a job as an assistant. Three years later, Collins no longer with the team, Jackson directed the Bulls to their first of six championships.

Immediately, Jackson set a tone distinct to that of the Draconian Collins. He operated with a subtle hand, using devices like movie clips to convey messages that words would flatten. During the Bulls' first championship run, he intercut sequences of the team with scenes from "The Wizard of Oz." Like the Wizard, Jackson was making his subjects realize the heart, courage and brains latent within them.

Jackson's use of movie clips isn't always touchy-feely, as was the case last year when he used scenes from "American History X" to prepare his Lakers for a playoff series against the Sacramento Kings. Primarily, he used the film and its underlying message of the brotherhood of man to unite his feuding stars, Kobe and Shaq. But he also took things in an altogether different direction by cutting back and forth between the film's Edward Norton character, who has a bald head and a tattoo of a swastika, and Sacramento's white, shaved-headed and tattooed point guard, Jason Williams. Then, according to the Washington Post, Jackson made comparisons between Sacramento coach Rick Adelman -- who has a mustache and distinctly German features -- and Adolf Hitler.

Indeed, for all the talk of Native American spirituality and Zen, Jackson often displays devilish cruelty. Cruelty is the yin to his New Age yang. Often it comes at the very moment of kindness, as was the case the day before a 1994 playoff game in New York. Jordan had taken his famous baseball sabbatical and Jackson sensed that his team was showing signs of buckling without him. To remedy the situation Jackson redirected the team bus as it made its way to the practice gym at the southern tip of Manhattan. Rather than practice that day, the team would take a ride on the Staten Island Ferry. However, before it got to its destination, Jackson had the bus stop and he ordered a longtime publicity assistant -- and the only female riding with the team -- off of the bus. According to Roland Lazenby, author of the Jackson biography "Mindgames," "the woman was devastated by the move and has never forgiven Jackson for an unexplained and seemingly unnecessary humiliation."

Such is Jackson's way. He demonizes those on the outside to tighten the inner circle. Coldly and without affect, he alienates the extraneous, and for much of this year the strategy seemed as if it might backfire. From the moment he arrived in L.A., Jackson had fostered a special bond with O'Neal. Often this connection came at the expense of the coach's ties to the younger -- and more independent -- star, Bryant. When the New York Times reported that Shaq was giving his teammates secret hand signals to not give Kobe the ball, the struggle between the team's two stars seemed set to consume the group.

Jackson tried to rectify the situation, telling him to turn down his individual game, to which Kobe replied, "I haven't even turned it up yet." Jackson even tried giving Kobe a book, "Corelli's Mandolin." When Kobe wasn't impressed by the story of a soldier who must sacrifice individual accomplishments for the good of his comrades, the coach's mean streak returned. He ripped Kobe in the media, accusing him of deliberately making his high school basketball games close so that he could provide last-minute heroics.

At last, it seemed that Jackson had lost his cool. If his behavior had not been directly detrimental to the team, it had failed to heal the rift between its two great players. But then, just when the media was ready to write the team off altogether, the magic returned. The Lakers won their last eight regular season games, and then dominated each series in the playoffs, sweeping all three opponents. Once again, Jackson has his team peaking at just the right time. If the Lakers sweep the NBA finals they will be the first team in history to run the entire playoff table.

On May 21, Jackson once again transgressed the laws of common sense to spectacular effect. Late in the third quarter of their second playoff game against the San Antonio Spurs, the Lakers trailed by seven. For the first time in 17 outings they seemed poised to lose. Out of what appeared to be frustration, Jackson picked a fight with a referee. First he got a technical foul for arguing a call. Then minutes later a ref told him to move off the edge of the court. When Jackson back-talked, the ref gave him a second technical, which carries with it automatic ejection. This type of distraction would unhinge most teams; for the Lakers it was a panacea. They rattled off the next seven points and went on to win comfortably.

It is the uncarved stone, the river ever constant and yet always changing. It is the Way of Phil. You cannot understand it -- you can only hope to contain it.

Shares