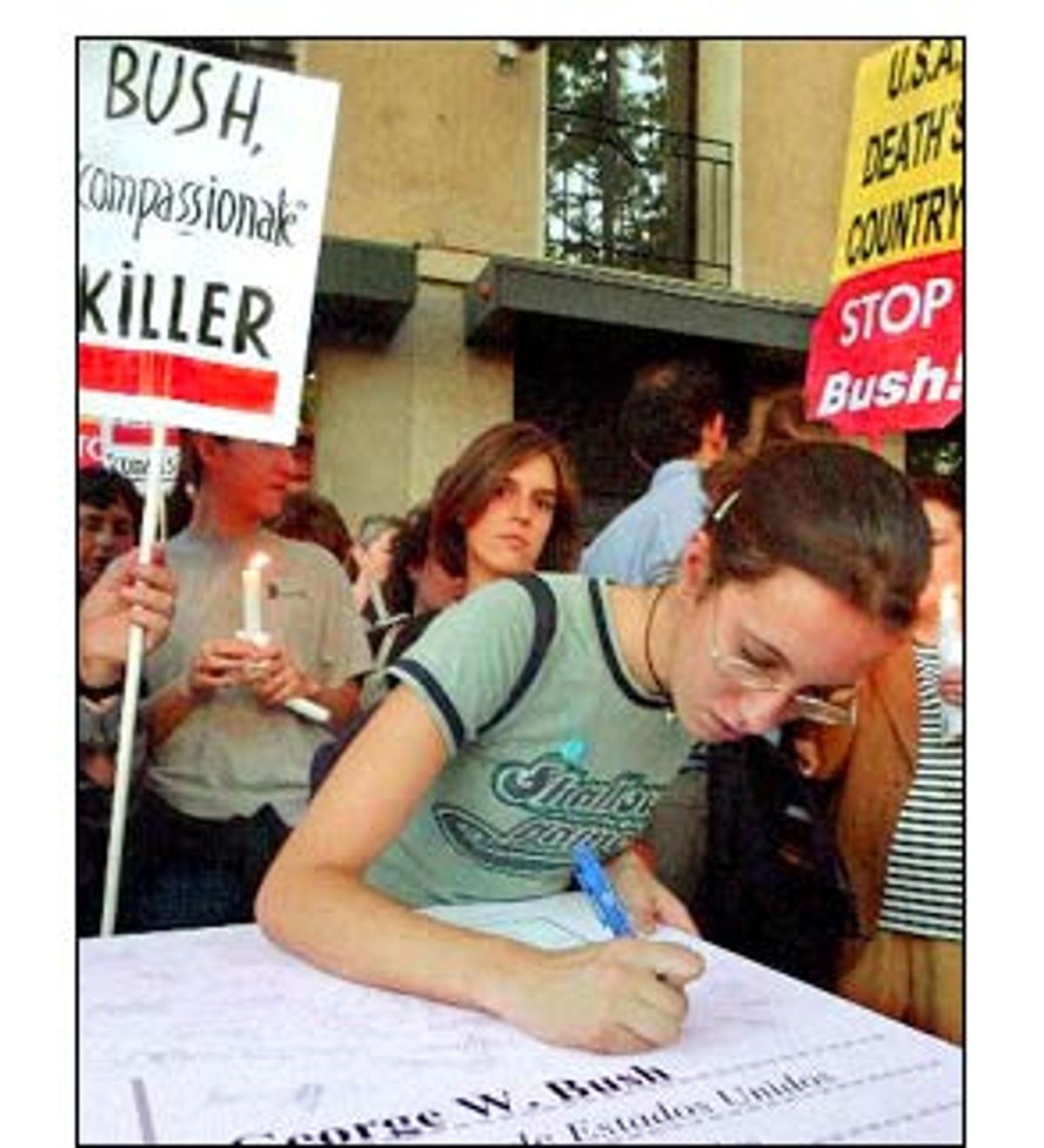

President Bush landed in Spain Tuesday on the heels of a death penalty whirlwind. Not just because of the Monday execution of Timothy McVeigh. Nor just because of the recent, highly publicized exoneration of Florida death row inmate Joaquin Martinez, a Spanish citizen who returned home to a warm welcome 48 hours before Air Force One touched down in Madrid.

Sure, those events were both controversial enough in the European Union, which prohibits membership to countries with the death penalty. But then Bush appeared to get into an argument with himself about one of the most controversial aspects of capital punishment: execution of the retarded.

"We should never execute anyone who is mentally retarded," the president told a group of European reporters who had asked him about growing concern from prominent American diplomats that execution of the retarded was impeding U.S. relations abroad. "And our court system protects people who don't understand the nature of the crime they've committed nor the punishment they are about to receive."

What made Bush's comments particularly remarkable: As governor of Texas, Bush himself presided over several executions of mentally retarded inmates.

Indeed, his governorship was literally ushered in with one such killing: the execution of inmate Mario Marquez on the day of Bush's 1995 inauguration. Bush did not, strictly speaking, sign off on Marquez's execution. But he did approve two other executions that drew worldwide condemnation: Terry Washington in 1997 and Oliver Cruz in 2000. Marquez, Washington and Cruz each "definitely had an I.Q. below 70," says Richard Dieter, executive director of the Death Penalty Information Center in Washington. An I.Q. of 70 is the universally recognized minimum for normal mental development.

As governor, Bush also authorized the execution of Johnny Paul Penry, who had an I.Q. in the 50s and a mental age of 6. Penry came within four hours of execution in 2000 when the U.S. Supreme Court stayed his execution; and last week, the court overturned his death sentence, saying the Texas legal system did not give jurors the proper opportunity for "morally reasoned" consideration of his retardation.

Bush's remarks -- coming just a day before his brother Gov. Jeb Bush signed a ban on executions of the retarded in Florida -- left White House staffers in damage-control mode, denying any shift in position.

The president "has always believed we shouldn't put people to death who are incompetent to understand the charges against them or the difference between right and wrong," senior White House communications advisor Dan Bartlett told Salon. But, he added, "there is some confusion" because in cases like Cruz's and Washington's, Bush believes that I.Q. is not the only measure of retardation. Bush, Bartlett said, believes that someone can learn to understand the difference between right and wrong regardless of I.Q.

The president, Bartlett added, continues to think that a ban on executing the retarded -- like the one signed by his brother and like a similar measure passed by the Texas Legislature that awaits action by Gov. Rick Perry -- is unnecessary. "The president believes juries are the appropriate body" to weigh a defendant's mental status, Bartlett said.

But while Bush defends putting on death row some defendants with I.Q.s in the 50s because they may not be retarded, there is growing alarm even among capital-punishment supporters that such cases profoundly undermine public confidence in the death penalty -- as well as place the U.S. at odds with every international standard of criminal justice.

Mental retardation and the special suggestibility of the mentally impaired are responsible for a large number of mistaken death sentences, which have received enormous publicity. The most recent case is that of Ronnie Burrell, who was exonerated and released after 14 years and one near-execution on Louisiana death row in January.

Even some of the cases of retarded defendants who actually are guilty can be hair-raising. Texas' Johnny Paul Penry, for example -- who has had his death sentence overturned by the Supreme Court twice in 12 years -- still believes in Santa Claus. Also in Texas, Cruz, convicted in 1988 of participating with an accomplice in the rape and murder of a young woman named Kelly Donovan, received his death sentence thanks to the plea-bargain testimony of his decidedly unimpaired accomplice. Cruz, with an I.Q. of 64 and a family history of schizophrenia, "waived" his Miranda rights and confessed -- a confession accepted by the courts even though the police officer who took it admitted on the stand that Cruz had no capacity to understand the words in his Miranda warning or what waiving rights might mean.

And then, when Cruz faced the sentencing jury, the prosecutor turned his mental impairment into the reason for his execution: "It makes him, in fact, more dangerous. It's part of the outlook of Oliver Cruz that makes him what he is," the jury was told. Cruz was executed in Texas in August.

This year, Human Rights Watch issued a report detailing false death row convictions in which retardation played a key role, such as the case of Earl Washington of Virginia, who has an I.Q. of 57. After a long police interrogation in 1983, Washington confessed to a whole series of crimes he never committed: a burglary, a rape and a fatal stabbing, the last of which landed him on death row. It took until 2000 before DNA tests fully exonerated him.

On Monday, a group of nine prominent retired U.S. diplomats filed a brief with the U.S. Supreme Court, which is considering retardation in death penalty cases, arguing that such executions so strongly violate world norms that they interfere with American foreign policy. Among the signers of the brief was Thomas Pickering, who represented the Reagan administration and the first Bush administration in El Salvador during the most contentious years of that country's civil war.

Proponents of capital punishment like Gov. Jeb Bush realize that when it comes to mental retardation, they have a problem. Even in Texas, recent polls show that the public overwhelmingly opposes the execution of retarded inmates like Johnny Paul Penry or Oliver Cruz.

And in Europe this week, Bush can expect to hear more about executions of the retarded and the death penalty in general. Twenty years after France abolished the guillotine, the European Union this year made abolition of the death penalty its top human rights priority worldwide. France now refuses to extradite any American criminal suspect who might face capital charges -- a refusal that reached crisis proportions for the Ashcroft Justice Department in the case of James Kopp, the accused shooter of Buffalo, N.Y., obstetrician Bernard Slepian, who is still being held in a Brittany jail. Germany is suing the U.S. over the execution of a German national never advised of his consular rights. And in the Republic of Ireland last week, voters overwhelmingly approved a referendum abolishing capital punishment from the constitution.

When a reporter asked Bush about capital punishment as he landed in Spain, the president said, "I refuse to let any issue isolate America from Europe." But the evidence suggests that the death penalty is already isolating the U.S. in Europe as it increasingly divides Americans at home.

Shares