In 1993, Scottish author Irvine Welsh published "Trainspotting," and changed popular fiction forever. Written in the phonetic Scottish dialect, it told the story of Sick Boy, Begbie, Spud and Renton, four working-class substance abusers living in the government-housing schemes of Edinburgh, Scotland. The life of an Edinburgh "schemie" is a busy one; fights are fought, drinks are downed, pills are popped, speed is snorted and large amounts of heroin are purchased regularly from Mother Superior, a local dealer inventively named for the length of his drug habit.

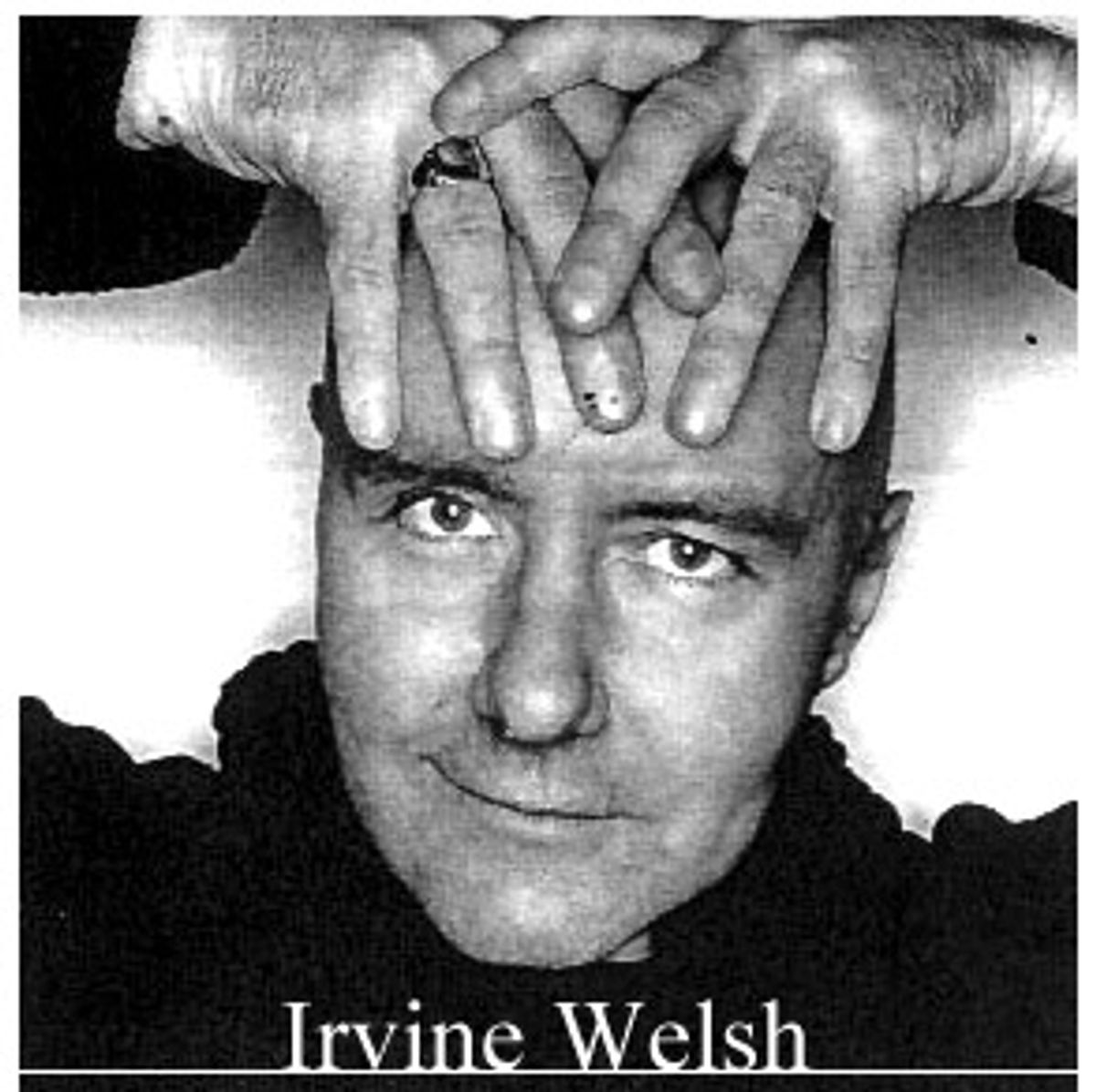

Suddenly, football was "fitba," sexual intercourse was "gittin yer hole" and Irvine Welsh was famous. A film adaptation starring Ewan McGregor, Robert Carlyle and Johnny Lee Miller became one of the most memorable films of 1996, with ample doses of explicit drug use, inventive and relentless profanity, frantic sex and violence.

A collection of Welsh's short stories, "Acid House," was published in 1994, followed by his second novel, "Marabou Stork Nightmares" in 1995, and "Ecstasy," consisting of three drug-related novellas, in 1996.

With the publication of the novel "Filth," in 1998, Welsh gave the world Detective Sergeant Bruce Robertson, a police officer in Edinburgh's Royal Lothian Constabulary. An antihero of the highest order, Robertson embarks on a suspect-molesting, drug-taking, hemorrhoid-scratching journey that ends explosively with his mental breakdown. The despicable Robertson shares narrative duties with a loquacious 3-meter-long tapeworm that lives coiled in his gut. It's a hoot. Really.

This May saw the publication of Welsh's new book "Glue," a sprawling novel that follows four friends across three decades. Set in the familiar territory of Edinburgh's squalid council housing projects, Billie, Carl, Terry and Gally first meet at school in the 1970s, listening to the Jam and the Buzzcocks, each desperately trying to lose his virginity. From there, we meet the friends at 10-year intervals for hilarious and heartbreaking updates on where life has taken them. In between going to the "fitba" and "gittin thir hole," each of the characters has to overcome his obstacles; some fare better than others do.

I spoke with Welsh recently about "Glue," "Trainspotting," his other books and his influences, the Brontës among them.

In many ways, "Glue" is a return to the familiar ground of "Trainspotting." It's set in the Edinburgh council housing schemes, and much of it is written in the Scottish dialect and revolves around the struggles of four young men as they grow up. Was this an intentional return to familiar subject matter?

Well, I think the similarity really is the fact that it's very much character-based rather than plot-based. I didn't really have a plot for this one. I just thought, well, I did want to get back to the feel of "Trainspotting," the idea that you've got these characters that are, sort of, sparking off each other and they generate the story from there.

I didn't mean it to be wider in scope, through the years and all that. The first part I wrote was 1990. It wasn't really going anywhere at that point so I moved forward to 2000 and I thought, well, they're not friends anymore and that's the story. But why are they not friends? So I kept going back between 1990 and 2000 and I couldn't really get the plot line. So I thought, I'll have to go back further to 1980 when they were just out of school and all that. So I got a picture of them at these different stages of life. I thought, I might as well go further back again and put the parents in so you can see where they've come from.

Normally, I like to have characters that are living in a short time frame in the novels, and put them in a position whereby they're having to overcome something. Like Renton [in "Trainspotting"] has to overcome his heroin addiction in a short time frame of about a year. Roy Strang of "Marabou Stork Nightmares" has to come to terms with his rape and being in a coma. Bruce Robertson from "Filth" has the murder and the mental breakdown and the tapeworm. It's like throwing stones at somebody over a short period of time and you get that kind of incendiary feeling that you're in their world. But "Glue" ended up a lot more expansive.

You mentioned Bruce Robertson from "Filth." To what extent does a fictional character represent your own state of mind? Were you going through a bad time when you wrote "Filth"? Robertson's a really despicable character.

Yeah he is. I've always liked to do that, though. I've always liked to get real bad bastards into fiction. When you read a lot of fiction, you can see that the person that's writing the fiction obviously wants to be seen as the central character. It's wish fulfillment. I try to get away from that. I like to have really bad horrible characters in the fiction. That was actually quite a good time for me. I felt quite upbeat when I was doing Bruce Robertson.

There are also some fairly unpleasant characters in "Glue." Do you think your readers and critics view you through your characters?

I always get this thing where people say, "Oh you must be really pissed off, or fed up, or depressed, or mentally ill, or crazy or something like that." The weird thing is that every time I've been to see people like poets, who write about flowers and trees and all this affirmation of life and the soul, and this upbeat, uplifting stuff, they're always really miserable bastards. They're always really fucking miserable depressed bastards. It's like comedians. They're always really miserable depressed bastards in real life.

When you construct such flawed characters, are you hoping that, despite their vices, readers will come to like and identify with them, or do you want readers to hate them unremittingly?

I like to empathize with somebody that you wouldn't normally empathize with, and see what's happening to them. It's much more interesting to me, to find something good in somebody that's really beyond the pale in a lot of ways. I think I was influenced by Bertolt Brecht's play "Mother Courage." He makes her terrible. Horrible. But there's something about her, something endearing about her in a strange way. Maybe that's why people take drugs as well. I mean, it gives them permission to behave badly. When people drink it gives them permission to be a kind of way they wouldn't normally be. And I think that's why there's something empowering about really bad bastards. Because they do things that we wouldn't normally do.

So you're living vicariously through them?

I think what I'm trying to do is get a reaction from them, to get a reaction from myself. I think when you write fiction you've got to get a reaction from yourself. Having said that, none of my characters could appear alien to me. Everybody's done things that they feel really bad about from time to time and feel that they've let themselves down. It's not habitual behavior. What you can do when you write is take a fleeting emotion and you can stretch it out into the whole character.

Do you think the use of phonetic vernacular Scottish in your books will keep American readers from your work?

My first book tour was about seven years ago and they keep asking me to come back so it can't be too bad. It means I'm never going to be like John Updike and top the New York Times bestsellers list automatically with every book I put out, or Stephen King or someone like that. What it does mean is, I think I'm going to be appreciated by people who are prepared to look for a wee bit more in literature and prepared to make a bit of an effort.

So is there a practical purpose to it, or is it solely to make readers expend a little bit of effort?

The reason I started to do it was because the characters just didn't talk like that or sound like that in my head. So I thought, if I do it in Standard English, why am I doing that? It's pretentious. Also, I was heavily influenced by the rave culture and acid house and all that and I wanted to get rhythms in it and beats into it, and Standard English isn't a very rhythmic language. It's not a very beat-y language. In the ministry of language it's an imperialistic, a sort of controlling, weights-and-measures kind of language. So it's not very funky, it's not got that kind of funk.

The kind of language that I use, a lot of the words are Gypsy words and it's a Celtic, oral storytelling tradition. It's very informative, it's got that aspect to it that drives it on for me, drives the story line on for me. When you think about it, the book is the last thing that you have Standard English in. I mean, you don't have it in films; nobody talks like that in films, even British films. You don't get it anywhere else. You don't get it in drama; you don't get it on TV. You would find it really strange if people spoke like that but you have to put up with it in a book. Why?

Again, as in "Trainspotting," "Acid House" and "Filth," "Glue" is set in Edinburgh. Do you think there's something unique about that environment, or are your characters universal?

I think they're universal. With "Trainspotting" everybody went on about it being a drug thing and all that, but it was about the characters. I go to Tokyo or Moscow or New York and everybody says, "Oh, we know a Begbie, we know a Sick Boy," and I think if you get good characters they have universal application.

Franco Begbie, the Scotch-drinking, punching-and-kicking psychopath from "Trainspotting," is perhaps one of the most vivid characters to arrive in contemporary fiction for decades. He makes a cameo appearance in "Glue," along with some other characters from "Trainspotting."

I think you get a virtual-reality world in your head. It's like, if you want a nutter, instead of just writing one and having to go through all the characteristics, you think, well, I've just got Begbie. You know he's in the same place around about the same time, so why not just have him as the nutter rather than just create another one? It's also a bit of responsibility as well, for the community. It's not a big community so, if you create another nutter from scratch, the impression is that everybody in Leith is a nutter, which they're not. Let's just stick with Begbie for that walk-on part. The problem is when I go home to Edinburgh. Every nutter in Edinburgh thinks that Begbie is based on them. So I have to try to tell them no, no, no.

How did you write "Trainspotting"?

I found a 1982 diary and that became the basis of "Trainspotting" really. It was all nonsense, it was all fiction. And I took a lot of notes when I was traveling on a Greyhound bus from New York to Los Angeles and that also became "Trainspotting." So it was a fiction of a fiction really. But that's what really kick-started the whole thing.

Were you surprised by its popularity?

Yeah, I was. I wasn't surprised that it got a lot of attention locally. I knew that the punters would like it because it is that sort of book, but I didn't think that the literati would like it and I didn't think it would travel as much as it has.

The film adaptation of "Acid House" will be released in the U.S. on DVD this August. It definitely deserves its R rating, with a lot of explicit language, drug use, sexual content and violence. You could even say it carries on where "Trainspotting" left off.

I thought, if we do "Trainspotting 2" it's just going to seem a bit crass. So, we've got license to just really go for it and not do an airbrushed film. A lot of the people in it are my mates who haven't acted before. We wanted to get people that didn't look like actors and really looked like real characters. It was never going to be a massive commercial film, but it was good to do a wee grungy kind of art-house film.

You make a cameo appearance in "Trainspotting" and again in "Acid House." Are you interested in getting more involved in cinema?

I can't act to save myself. The directors are pretty clever; they always give you a wee part if you want one because it stops you from criticizing the film if you don't like it. Not that I would anyway because I like both the films.

You've become an influence to a generation of writers. Who are your literary influences?

My influences are a lot of classic Scottish fiction. James Matthew Barrie was the first Scottish writer I read. I just read all the big Scottish writers like Alisdair Grey, Iain Banks and James Kelman and all that. American stuff as well, like Beat stuff: Burroughs, Kerouac, Bukowski. Modern American fiction as well, like Gary Indiana and Joel Rose. Southern writers like Faulkner and Cormac McCarthy. Just about everything really. I'm influenced by Dostoevski and, not so much Tolstoy, but Tolstoy as well and even all the classic English stuff that you wouldn't think, like the Brontës and all that kind of stuff.

Why such a brief reading tour?

I really should spend more time over here. I'm over here for three weeks. I was talking to somebody who spent six weeks over here, doing a bit, and you can't do it. It just fucks you up. It means that you're talking about the book constantly for six weeks. Even after a few days I find myself becoming strangely autistic about it. I'll probably end up in the funny farm after just three weeks.

Shares