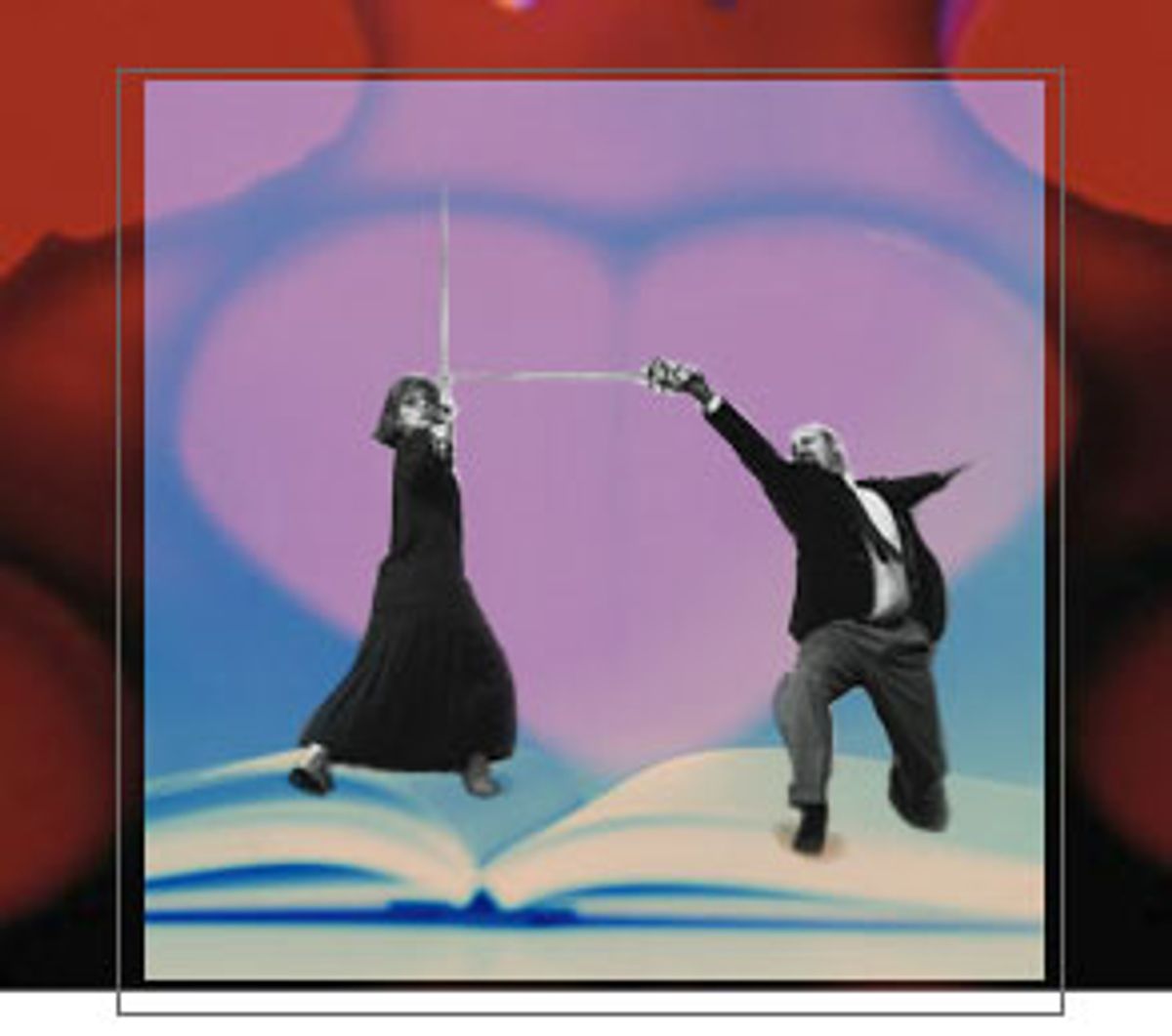

Everyone knows that you should never sleep with your teacher. I had an aunt who also recommended that you should never sleep with a writer, or anyone who has been on the stage. And anyone in the writing business knows that a writer should never sleep with, nor fall in love with, another writer. A worst-case scenario, then, would be sleeping with your writing teacher. You would find yourself hellbent on a desperate struggle for control of the narrative. Imagine. Two competing storytellers trying to plot an epic Russian drama. (With two writers involved, it's not going to be a small affair, is it?)

Now, I'm not saying that Andrew Motion, England's poet laureate, slept with his creative writing pupil Laura Fish, or she with him. As a matter of fact, what actually happened between these two people is a subject about which a really titanic struggle for the narrative is going on. For one thing, there are more than just two combatants; while it's starting to look like Motion's recent indiscretions with his student at the University of East Anglia are a story after all about not very much, it's also clear that the British press have a competing interest and would like to shape a more salacious tale for their readers.

Traditionally, the post of England's laureate goes to the cuddly poets, the relentlessly establishment Oxford and Cambridge types who mind their pens and quips when the queen is around. The laureate before the present incumbent, Andrew Motion, was Ted Hughes, an appointment that surprised everyone because Hughes was a caveman, and some sort of shaman to boot. When Hughes died, it was back to the cuddly, the safe, the reliable; and the eminently polite chap got the job. But oh dear. A sex scandal. Well, nearly a sex scandal. All right, a scandal about sex but with no sex. Certainly no Blue Dress. Please.

Motion teaches creative writing at the University of East Anglia, on an M.A. course until recently considered to be the finest in the country. He stands accused of harassment by Fish. He in turn says that Fish has been slandering him to the press, and counterclaims harassment by her. The case bubbled as the university tried to establish who did what and to whom. Meanwhile, Motion continued to give his tutorials to Laura Fish, watched over by the dear old dean of the university. Well, God bless the dean. I'll bet you could strike a match on that atmosphere as the two politely disagree on the effectiveness or otherwise of a subordinate clause.

Neither Motion nor Fish denies that they exchanged some 40 intimate e-mails in the course of just a few weeks. Neither party denied that tutorials were concluded with a "kiss and a hug." Also not denied was that Motion, married with three children, visited the student at her apartment. It seems that this flirtation went on for some considerable time, and to the apparent satisfaction of both parties.

Andrew Motion is not a poet in the Byronic cast. He is not dashing (except when seen hurrying away from the UEA -- until recently, the only complaint about him was that he was infrequently there) and neither is "passionate" an epithet that might attach to him. On the contrary, there is about him something of the manicured and tinctured mannequin. He has a fussy -- some have said foppish -- obsession with grooming and exquisite designer clothes. He also speaks in an extraordinarily strangled accent, as if the snobbish and anachronistic values of Oxford gentility have only been half-swallowed. His verse is clipped, precise, brilliant and curiously antiseptic.

And the tender young mind he was alleged to have preyed upon? Laura Fish is a 37-year-old single mother. She is also the author of a published novel, and is currently studying for an M.A. at the university. Motion interviewed and accepted her into the course after being impressed by her book. She has been a teacher of writing herself, and still is.

Of course, it makes no difference how old, experienced or well-versed someone is, or whether they have a daily manicure. Harassment is harassment and the offense needs to be treated seriously. If offense it is. There is no suggestion that Motion threatened to fail Fish or adjusted grades or committed any of the other forms of moral turpitude associated with philandering professors. The exchange of "personal" e-mails had always been a two-way thing. Jan Dalley, Motion's American wife and herself a respected writer, claimed that Fish had a "crush" on the poet and had telephoned their London home several times.

Because of the power dynamic involved, there are damned good arguments for not allowing college professors to have relationships with their students. Like lawyers and their clients or shrinks with their patients. Like agents with their starlets or editors with their writers. Like factory supervisors with their underlings or the assistant quality control manager with the subassistant quality control manager. But if we're going to prosecute such behavior even in those cases where everyone agrees that the flirtation was mutual and authority wasn't abused, then we're going to need several thousand more lawyers in the land.

So what the hell was this all about? Why can't the dear old dean be allowed to get on with his job? Well, he can now, because after a full inquiry, everyone has been exonerated. No wrongdoing of any kind found anywhere. Thank goodness.

Except that, in the process of admitting evidence, Laura Fish had a fine character reference drawn up for her by Douglas Dunn, a Scottish poet of considerable repute, an erstwhile colleague of Motion's and -- some would say -- a professional rival. Motion wrote an angry letter to Dunn, hinting at Fish's shortcomings. Dunn in turn showed it to Fish. Gosh, the press even got to hear about it. Now Fish is seeking further redress, accusing Motion of trying to ruin her reputation and endangering her chances of employment. More litigation.

Perhaps writers should never be allowed to get together in a workplace context. It's not like studying computer science, after all. The emotions are at large, and are shared and are questioned. There is a vulnerability. Jan Dalley, a shining light in this sorry affair, has said that crushes are bound to happen in writing groups because "they talk about emotions."

British novelist Anna Davies, who also teaches an M.A. writing course, says, "Contrary to popular belief, writers do not typically lead glamorous lives. The writer spends most of his or her time in a tiny room, trying to force words out on to a blank page or screen. It is a lonely and frequently boring existence, and sometimes you wonder if anyone is actually out there listening to you. Think how wonderful it is, then, to emerge into a room full of people who think you are something special." Pity, then, the sap who does this for a living. And forgive him or her who thinks, when someone takes an interest, that they are living out that epic Russian drama.

Legislation against harassment has been a hard-won victory, because women in the workplace do need protection against sexual predators. But most people know the dividing line between flirting that is fun and attention that is unwelcome. Harassment legislation exists for those cases where predators persist beyond the word "no." But after which personal e-mail does the conversation become "unwelcome"? The 40th? After how many hugs and kisses? If Fish told Motion to stop and he persisted -- which doesn't seem to be the case -- then her complaint would have some grounds, but the guy is a poet, not a psychic. The mechanisms set up to protect people from workplace harassment were never created to deal with romance gone sour.

This appears to be a story of crushes and cold feet, with both people in the wrong. No one knows how it became an issue of harassment. But, with the machinery for handling genuine harassment cases in place, the university has to endure the unfolding of this nondrama as the stupidity and childishness of two "mature" writers becomes a public comedy. This is the highbrow version of running to the tabloids, a litigious rendition of kiss-and-tell. But what is most outrageous is that the dean of a university, instead of getting on with his important job, has to spend hours umpiring the cooling of an affair that never even really got going.

This isn't the business of the dean. This is just the trailing, messy stuff of life. Perhaps it would have been better if something had happened. Closure might have come with a few bitter tears on one side or the other, instead of this endless poison dribble of litigation, feuds and press leaks. Of course, the proper, grown-up place for these writers to deal with what did or didn't happen is on the page. With full-throttle vitriol and extreme prejudice if necessary, but neatly paragraphed and with no ineffective use of the subordinate clause.

Freud's celebrated conclusion was that everyone who writes does so in search of "fame, fortune and the love of women." Well, now they've both got the fame. Fish, who is writing a book on harassment, may even get the fortune out of all this. As for the love of women, you would have to ask Jan Dalley what she thinks of the pair of them.

Shares