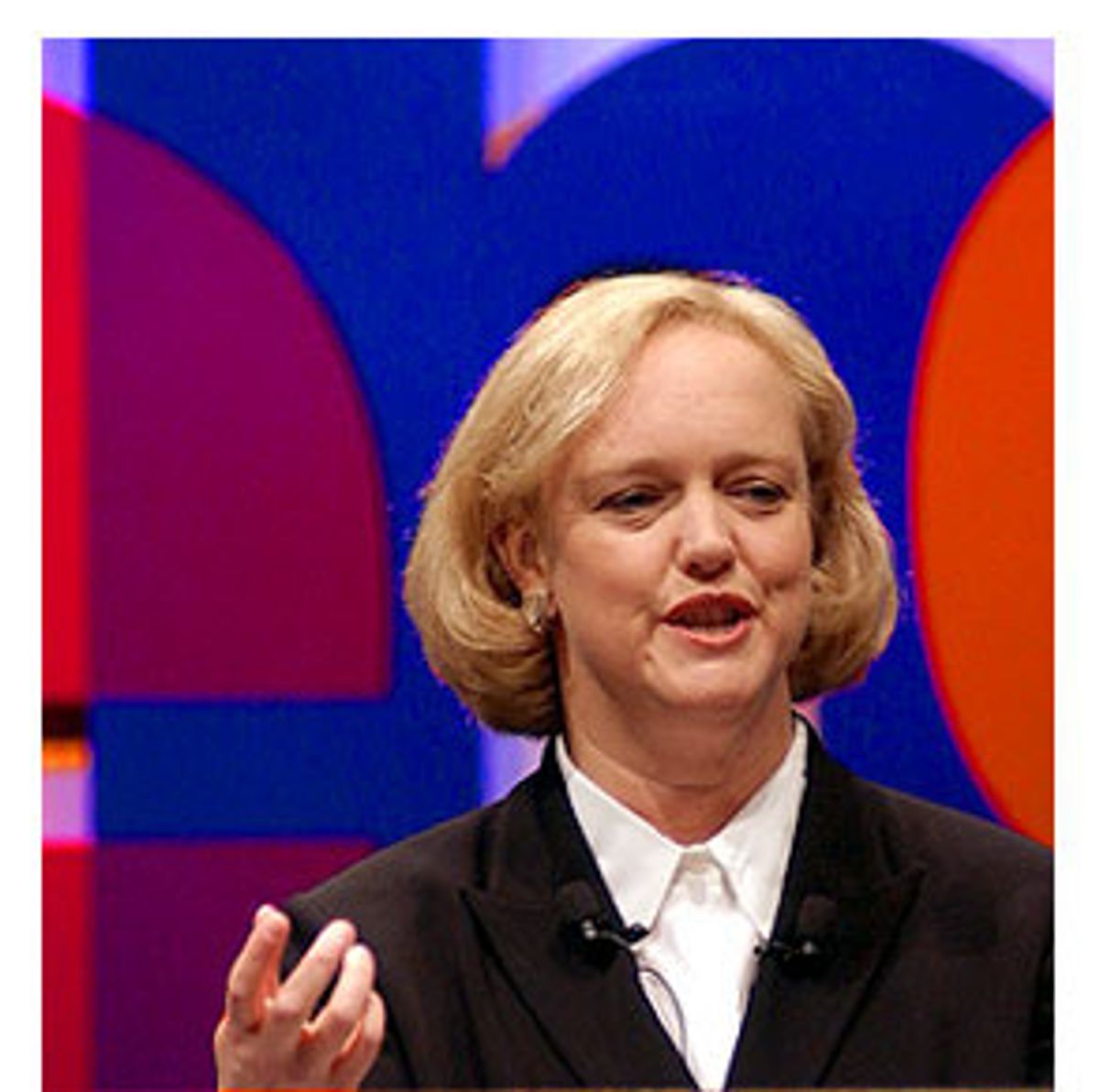

When Meg Whitman took over as chief executive of eBay some three years ago, she set about her work with her usual mixture of know-how and curiosity. She knew she had to build the eBay brand. But she also listened to the auction site's founders and conferred closely with them. Her style -- collaborative yet decisive, serious but loose -- set the tone for the company.

Sure, Amazon.com founder Jeff Bezos was Time magazine's man of the year, and Tim Koogle was the new-media savant who made Yahoo the top Web portal, but Whitman was the old-fashioned, low-key manager. And the tortoise has beaten the hares. Yahoo has slipped from profitable to unprofitable, and Wall Street wonders if the never-profitable Amazon.com will survive. But eBay is doing fine; Wall Street complains that its stock is too expensive, but the company is worth more than four times as much as Kmart, and Whitman is leading it into its sixth very profitable year in a row.

Now, the down-to-earth Whitman is starting to get her due. Worth magazine named her No. 5 on its list of "best" CEOs. Fortune magazine ranked her the second most powerful woman in business, behind Hewlett-Packard chief Carly Fiorina and right ahead of Oprah Winfrey. All this, without the star-quality charisma of Fiorina or the electric energy of Amazon.com founder Jeff Bezos. Instead, Whitman still works in what amounts to a large cubicle, dresses casually and sometimes responds personally to customer e-mails. That's despite owning more than $600 million worth of eBay stock.

While dot-com bubbles are bursting all over, Whitman runs an international e-commerce giant whose customers used eBay's person-to-person auctions to sell $2.36 billion worth of Beanie Babies, baseball cards and other merchandise in the three months ended Sept. 30 (which means the eBay economy is larger than that of Iceland). Meg Whitman stands as the most successful Internet executive of all.

Although Whitman didn't invent eBay, she did usher it from a start-up to a powerhouse. Since taking over as CEO in May 1998, she kept eBay focused on its core competencies. Any expansion was gradual and auction-related, from acquiring similar online-auction companies overseas to buying Half.com, a marketplace for selling used goods at set prices. She kept the company concentrated on what users would want, either as a permanent enhancement or a one-day special offering. From the start, she understood what makes the company tick. "What is really interesting about eBay," she told one interviewer, "is that we provide the marketplace, but it is the users who build the company. They bring the product to the site, they merchandise the product and they distribute it once sold."

Indeed, Wall Street observers claim that eBay runs so smoothly, it's difficult to point to what management has done. Whitman's contribution is, to some extent, taken for granted. Her lack of dot-com flamboyance shouldn't obscure the fact that she's always been driven -- even in college she had the Wall Street Journal delivered to her Princeton dorm room. Her low-voltage but efficient style is precisely what makes Whitman a business executive worth praising.

Margaret C. Whitman took an offline route to her online triumph. Born in 1957, the Long Island native graduated from Princeton University in 1977, then got her MBA at Harvard in 1979. She started her career in brand management at Procter & Gamble, a sort of school for brands and a great breeding ground for future Internet executives, including America Online co-founder Steve Case. Whitman then worked for eight years at consulting firm Bain & Co. From 1989 to 1992, she was an executive at Walt Disney, where she opened the first Disney stores in Japan and learned the basics of how to make a business run smoothly. She then moved to shoemaker Stride Rite, where, among other accomplishments, she helped revive the Keds brand.

Whitman got her first real taste of the spotlight in 1995, when she joined Florists' Transworld Delivery (FTD), initially as president and then as CEO. Whitman oversaw FTD's conversion from a money-losing, florist-owned cooperative to a profitable private company, and she rejuvenated the FTD brand. But infighting at FTD frustrated her, and she left to head Hasbro's Playskool division. About a year later, a headhunter approached her about a top job at eBay.

In an origin that's worthy of its Web lore, eBay started in 1995 as a vehicle for founder Pierre Omidyar to help his then-girlfriend collect Pez dispensers. Omidyar's site grew quickly. Its listings now include automobiles, antiques, real estate and computers, and some users even make their living selling on eBay. But in early 1998, the company was known as Auction Web and had about 20 employees.

And Whitman didn't need the job. She was overseeing 600 Playskool employees, she had two sons and her husband, Griffith Harsh, was head of neurosurgery at Massachusetts General Hospital. As she told Business Week, she wasn't interested -- "I'm not thinking about living 3,000 miles across the country, uprooting my neurosurgeon husband, and taking my two boys out of school, to go to the West Coast for this no-name Internet company."

The headhunter persisted, however, and Whitman agreed to meet Omidyar. Whitman is all about brands, and as she got to know the company, she realized that it had the makings of a great brand. And Whitman knew she was interested in the Internet -- Amazon.com was already a well-known phenomenon, for example. So she joined and helped eBay go public four months later.

Whitman also set about making eBay more corporate. She created the company's first national advertising strategy. She recruited executives from places such as PepsiCo. She pushed for stores and companies to sell on eBay, so now corporations such as Sun Microsystems sell millions of dollars worth of products a year via the site. She encouraged eBay to offer various specialty sites under the eBay umbrella -- much the way FTD's global Web site, under her watch, included individual florists' shops under the FTD banner. Whitman also installed a trust and safety program, which offered insurance for buyers. In making the place more corporate, she made it more professional.

It's true that much of the credit for eBay's success must go to its business model. It's an ingenious blend of yard sale, classified ad and auction. Have an old sailboat you want to get rid of? List it on eBay, accept bids for three or maybe five days, then sell it to the high bidder. eBay gets a small fee for listing the boat, then a tiny commission from the sale. The appeal extends beyond the guy down the street. None other than Warner Brothers used eBay to auction off an old sailboat, only in this case it was the boat featured in the film "The Perfect Storm," and the price was $145,000.

The beauty of eBay's model is that the company just facilitates the listings and the sales; it doesn't have to make or transport any goods or carry any inventory. The users build the company, as Whitman said. As a result, eBay may collect as little as 6 percent on each sale, but most of that is profit. It's truly the sort of business that couldn't exist offline.

As wonderful as eBay's business model may be, that didn't guarantee a viable business. Whitman made the model work. She paid attention to that eBay community, allowing it to help guide the site and develop innovations like customized online storefronts. As Web traffic soared, eBay suffered several outages, including one that lasted more than 20 hours; Whitman's staff responded by e-mailing and calling customers and refunding millions in fees. The eBay brand kept customers loyal.

That loyalty is crucial -- the site's newsletter boasts of how eBay brought people together and saved small businesses. "eBay is an outstanding example of loyalty," said Bain & Co. consultant Frederick Reichheld, author of "Loyalty Rules!" He notes, for example, that eBay built a costly system to respond to customer e-mails within 24 hours. And thanks to this attention to building loyalty, more than half of eBay's customers come by referrals from other customers. Whitman managed to expand the company without destroying its community, maintaining what she calls "the small-town feel on a global scale."

Whitman's moves haven't always pleased all customers; she drew some flak, for instance, when she scaled back opportunities for users to post complaints on the site and when eBay held a charity auction that some called self-serving following the World Trade Center attacks. But Whitman kept most users in the fold as she moved the company forward. That allowed her to go after more big-ticket items. For example, in 1999, eBay acquired Butterfield & Butterfield, a traditional auction house that ranked a distant third behind Sotheby's and Christies. The purchase threatened to turn off the little guys who had built eBay. However, it helped eBay later develop online auctions of fine art and rare collectibles.

Among Whitman's key achievements was fending off the competition. As authors David Yoffie and Mary Kwak point out in their book "Judo Strategy," Whitman was mindful of America Online, Amazon.com and Yahoo, because any one of these might have plunged into online auctions and crushed eBay early on. So when Whitman's team deepened the company's relationship with AOL to eventually make eBay AOL's exclusive auction provider, it wasn't just a great way to connect to AOL users -- it also forestalled AOL from becoming a rival.

That bought eBay time, which was crucial because the site was building critical mass. The large customer base meant eBay was the place to sell; more sellers attracted more buyers; that attracted more sellers; and so on. eBay achieved what business pundits call "The Network Effect": the network becomes more valuable to its users simply by adding more users. The Internet is the perfect example of this, but eBay may be a close second.

Yahoo threatened the company in late 1998 by offering free auctions. But eBay didn't drop its costs. Whitman and her team discovered that eBay's small fees discouraged people from listing any old junk, so it provided a measure of quality control that Yahoo didn't have. By the time Amazon.com tried auctions in 1999, eBay already had a solid lead. To Whitman, Amazon.com's only advantage was its prodigious credit-card processing capabilities. So later that year, Whitman decided to buy Billpoint, an online system that allows payments by e-mail.

Although eBay has been under the gun for years, Whitman remains a steady presence. Colleagues describe her as consistently upbeat. It seems she draws strength from her other passion, her family. Fortunately, her husband now works at nearby Stanford University Medical Center. She likes to escape to his family farm in Sweetwater, Tenn. She goes fly-fishing a few times a year -- and yes, she's bought fly-fishing equipment on eBay. That's in addition to the Beanie Babies, Pokemon cards and even a car that she purchased there.

Whitman may be calm, but she's ambitious. So even as she moves quickly to defend her company's turf, she's also looking to broaden it. For example, she wants to expand eBay overseas; just this year she bought iBazar (which has online auction sites in eight European countries) and made moves in New Zealand, Korea and other countries.

Still, she eschews top-down command tactics that assume she knows everything. Instead, she remains open to opportunities. For example, customers gravitated toward the fixed-price sales of Half.com, as opposed to auction sales. So Whitman championed fixed-price sales on the site, and those may one day put eBay on top of Amazon as the Web's biggest retailer.

Even eBay isn't immune to hubris. Whitman says eBay aims to more than triple its annual revenue to $3 billion by 2005, and Wall Street considers that implausible. Yet in her professional hands, that claim isn't so much a dot-com boast but a CEO setting the bar high for her team. So let others try to revolutionize media or make bookstores obsolete, while Whitman keeps her eye on the bottom line. Because in the long run, Meg Whitman's success reminds people that this e-commerce thing may just work after all.

Shares