Even before Sept. 11 forced the West to face the cultural friction between it and the Arab/Islamic world, there was an unwarranted sense of superiority. The renowned Italian journalist and interviewer Oriana Fallaci wrote Arab culture off as a few interesting architectural flourishes and the Quran. Apparently, it's easy to forget that history is cyclical and the roles were once reversed. A millennium ago, while the West was shrouded in darkness, Islam enjoyed a golden age. Lighting in the streets of Cordoba when London was a barbarous pit; religious tolerance in Toledo while pogroms raged from York to Vienna. As custodians of our classical legacy, Arabs were midwives to our Renaissance. Their influence, however alien it might seem, has always been with us, whether it's a cup of steaming hot Joe or the algorithms in computer programs. A little magnanimity is called for.

A is for algebra

From "al-jabr," Arabic for "restoration," itself a transliteration of a Latin term, and just one of many contributions Arab mathematicians have made to the "Queen of Sciences." Al-Khwarizmi (c.780-c.850), the chief librarian of the observatory, research center and library called the House of Wisdom in Baghdad, was the man responsible for making my life miserable at school. The motivation behind his treatise, "Hisab al-jabr w'al-muqabala" ("Calculation by Restoration and Reduction": widely used up to the 17th century), which covers linear and quadratic equations, was to solve trade imbalances, inheritance questions and problems arising from land surveyance and allocation. In passing, he also introduced into common usage our present numerical system, which replaced the old, cumbersome Roman one. Al-Karaji of Baghdad (953-c.1029), founder of a highly influential school of algebraic thought, defined higher powers and their reciprocals in his "al-Fakhri" and showed how to find their products. He also looked at polynomials and gave the rule for expanding a binomial, anticipating Pascal's triangle by more than six centuries. Arab syntheses of Babylonian, Indian and Greek concepts also led to important developments in arithmetic, trigonometry (the algorithm, for instance, thanks to al-Khwarizmi) and spherical geometry.

B is for backgammon

Sheshbesh is what it's called in Beirut and Cairo, whence the savviest players hail. Although this beautiful waste of time dates back to the pharaohs, the form we enjoy today came to us via Moorish Spain in the 10th century. Ghioul and moultezim are two other variants of "the game of kings," popular wherever the happy hookah is indulged.

C is for cough medicine

Necessity being the mother of invention, the Arabs were the first to distill water, for long journeys across areas (such as the Sahara) where supplies were uncertain. Their experiments with various chemical compounds also gave us ethanol alcohol, sulfuric acid, ammonia (have you ever noticed the uncanny resemblance between Mr. Clean and the genie in "Thief of Baghdad"?) and mercury. In applied chemistry they discovered better and more efficient ways for tanning leather and forging metals. Messing around with mortars and pestles produced camphor, pomades and syrups.

D is for Dante

Her countryman Silvio Berlusconi echoed Fallaci's ill-spoken sentiments that, on the whole, Western civilization was superior to that of Islam. She said she was quite happy with Dante, thank you very much. She spoke too soon. Though the theory has long incited fierce debate, Dante may have been acquainted with "ascension literature," a fantastical literary genre that deals with Mohammed's ascent to Heaven (using a spiraling, magical ladder; ascension literature is still popular in the Middle East and Africa). Dante was undoubtedly acquainted with Avicenna and Averroes ("who made the great commentary"), assigned as they are to that benign circle of the Inferno reserved for pagan and non-Christian worthies known as Limbo.

Moreover, according to the dean of Arabic literary studies, the formidable Robert Irwin, "a full understanding of the writings of Voltaire, Dickens, Melville, Proust and Borges, or indeed of the origins of science fiction, is impossible without some familiarity with the stories of the Arabian Nights." Aladdin, Sinbad the Sailor, Ali Baba and Scheherazade, archetypes each and every one, are honorary members of the Western canon. The mock, allegorical travelogues and cautionary tales of Montesquieu, Voltaire, Johnson and other 18th-century writers and philosophes, are inconceivable without the garrulous, wayward conceits of "The Arabian Nights." They're detectable as well in the parodic chivalry of Don Quixote and in Calvino's postmodern children's fable "Marcovaldo."

E is for equestrian

Although the ancestors of Mr. Ed and Secretariat probably originated in Central Asia (with the "Heavenly Horses" of the King of Ferghana), our equine friends were first bred for speed in the desert sands of the Empty Quarter. Arab historian al-Kelbi (c. 786) traced the Arabian to the pedigreed horses of Bax, great-great-great grandson of Noah. The conquest of the Arabian Peninsula, North Africa and Spain was due in no small part to the aptly named beast (and the indefatigable camel), mount of choice for the tribesmen who swept all in their path. The descendents of these terrible swift steeds were brought to the New World by the Conquistadors, to devastating effect, particularly in ancient Peru where the Incas mistook the horsemen for gods. (By the time they learned the truth it was too late.) Appropriately enough, the largest and most successful stable today belongs to Sheikh Maktoum of Dubai.

F is for Fitzgerald

Edward, translator of that beloved chestnut of yore, "The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam" (a jug of wine, a loaf of bread -- and thou). My concern here, of course, is not with Fitzgerald, nice duffer though he was, but with Khayyam himself (1048-1131) -- gifted physician, Persian bard and geometer extraordinaire. In his seminal "Algebra" he attempted a fusion of algebraic and geometric methods, discussing the solution of cubic equations by geometric means, anticipating analytical geometry. (Descartes took up this thread 500 years later, though it's unlikely he knew Khayyam's work.) Khayyam also dabbled in astronomy, his lunar calculations leading him to reform the calendar in 1079 (there are references to this throughout the Rubaiyat). Furthermore, Islamic astronomers invented the pendulum, improved upon the sundial, prognosticated the existence of sunspots and studied eclipses and comets. And al-Biruni calculated the length of the solar year to within 24 seconds and discussed the earth's rotation on its axis -- 500 years before Galileo. Arabian and Islamic astronomers also constructed the first observatories, in Toledo, Cordoba, Baghdad and Cairo.

G is for guitar

If the Moors had known they would be responsible for the spectacle of Mick Jagger shaking his scrawny ass onstage into his late 50s, they might have thought twice about schlepping the early prototypes of the instruments that make up the typical rock band to Spain and Southern Italy. Percussion in the form of cymbals and timpani, bowed instruments, the lute (from "al-ud," the wood; see "The Buena Vista Social Club" for more), the Spanish guitar (or guitarra morisca as it was originally called 800 years ago), the zither (brought west from Greece), the dulcimer began keeping the neighbors awake as early as the 9th century. There's also that unique Near Eastern sound and rhythm, which, aside from early Spanish music, made itself felt in 18th-century classical music, most famously in Mozart's "The Abduction from the Seraglio." (Turkish things were so "in" then. Witness all those wonderfully exotic 18th-century Venetian scenes by Longhi and Reynolds' costumed, turbaned toffs.) Miles Davis accented the "Oriental," Near Eastern strain in his "Sketches of Spain." The godfather of world music, Davis incorporated Middle Eastern elements into his fusion of jazz and rock in the late '60s and '70s. Nowadays nobody thinks twice about such hybridization.

H is for "Havi"

Expanding on the legacy of the Greek physician and philosopher Galen was Rhazes (c. 865-c. 930), the greatest doctor of the Middle Ages. His extensive medical treatise in nine volumes, "Havi" ("The Virtuous Life"), was used as a textbook in the Sorbonne as late as 1395. In addition to case studies and clinical reports that still have anecdotal interest, Rhazes also wrote a celebrated monograph on smallpox. (Knock wood.)

"The Book of Healing," by the Persian physician and philosopher Avicenna (980-1037), is a masterwork on hygiene and therapeutics that was used as a reference well into the 16th century. With Averroes (1126-1198), the Andalusian physician and philosopher, Arabian medicine attained its peak. Muslim surgeons in the 11th century knew how to treat cataracts and internal hemorrhaging, and they pioneered the usage of anesthetics, which they derived from herbs. Arabian hospitals anticipated our modern ones in combining teaching facilities and libraries, and in offering specializations such as internal medicine, opthamology, orthopedics and pharmacology (on the last, Ibn al-Bayter, who died in 1248, described 1,400 different medicines of vegetable and mineral origin alone). They also set standards for cleanliness and hygiene that in the West shamefully weren't met till the 19th century.

I is for Ibn Khaldun of Tunis (1332-1406)

He invented the scientific study of history (and, indirectly it could be argued, sociology) centuries before the French Enlightenment, Hegel, Weber and Braudel. His "Muqaddimah" ("The Prolegomena"), the introduction to a general survey of Islamic history with a specific focus on North Africa, was begun in 1377 and updated several times to account for sociopolitical changes. In it, he attempts to order the raw material and outward phenomena of history under basic principles.

"Wise and ignorant are at one in appreciating history, since in its external aspect it is no more than narratives telling us how circumstances revolutionize the affairs of men, but in its internal aspect it involves an accurate perception of the causes and origins of phenomena. For this reason it is based on and deeply rooted in philosophy, worthy to be reckoned among its branches.

"Human society in its various manifestations shows certain inherent features by which all narratives must be controlled ... The historian who relies solely upon tradition and who has no thorough understanding of the principles governing the normal course of events, the fundamental rules of the art of government, the nature of civilization and the characteristics of human society is seldom secure against straying from the highway of truth ... All traditional narratives must invariably be referred back to general principles and controlled by reference to fundamental rules."

Of Olympian detachment, Ibn Khaldun was less prone than most historians, then and now, to fiddle the books and force facts to fit preconceived theories. He saw that the course of history is governed by the balance of two forces, which for him were the nomadic and the settled life. He identified history with civilization and, having established this theory, expounded in minute detail upon civilization in all its religious, administrative, economic, artistic and scientific layers.

Ibn Khaldun briefly made headlines in the early 1980s, when President Reagan quoted him in a speech. His name mystified the White House press corps, driving them to their encyclopedias to bone up on this Ibn guy; within hours they were speaking knowledgeably of him. As an undergraduate at the time, I was taking a yearlong seminar entitled "Oriental Humanities." One of our assigned texts in the Arabian section was "Muqqadimah." Professor Meskill, an old China hand, informed us of the Great Communicator's "erudition." We all had a good laugh.

J is for jihad

This word, which has been misinterpreted as "religious war" but really means "an effort" or "striving," is one of many Arabic words that have entered the English language. Besides mullah and ayatollah, which have also acquired pejorative connotations, a partial list of Arabic words or derivatives thereof includes: alcohol, orange, coffee, sofa, caravan, tariff (from Tarifa -- the village through which the Moors invaded Spain, near Gibraltar), citrus, lemon, alembic, algebra, chess, sugar, cataract, magazine, seraphim, arsenal (also the name of a London soccer club, Osama bin Laden's favorite, appropriately enough), apricot, sandal, Satan (from "Shaitan," the Evil One), rice (from "al-ruzz"), sherbet and sorbet, talisman, artichoke, rack (from "arrack," perspiration, also the name of the fiery spirit, raqi; wrack your brains on that one), almanac, alcove, albatross (from "al-kadas," which the Portuguese corrupted into "alcatraz"; now what would the author of "Kubla Khan" make of that?), castle (from "alcazar"), albacore, Abyssinia, ginger, ghoul, zircon (from which we derive "jargon," one being a mixture of stones, the other of tongues), banana (from "banan," finger or toes), nadir, zenith, cipher, zero and monsoon (from "mausim," or season).

K is for kebab

Next time you're munching on a Nathans, or, in my case, disputing the nutritional value of chorizo with the missus, you have the Moor to thank. Cured meats and sausages and the humble kebab, usually lamb or beef (never pork), were among the culinary delights that came to Europe via Islamic Spain. Likewise the hotter spices and spicier condiments. The Moors were also the first to crystallize sugar (which they also brought to Europe).

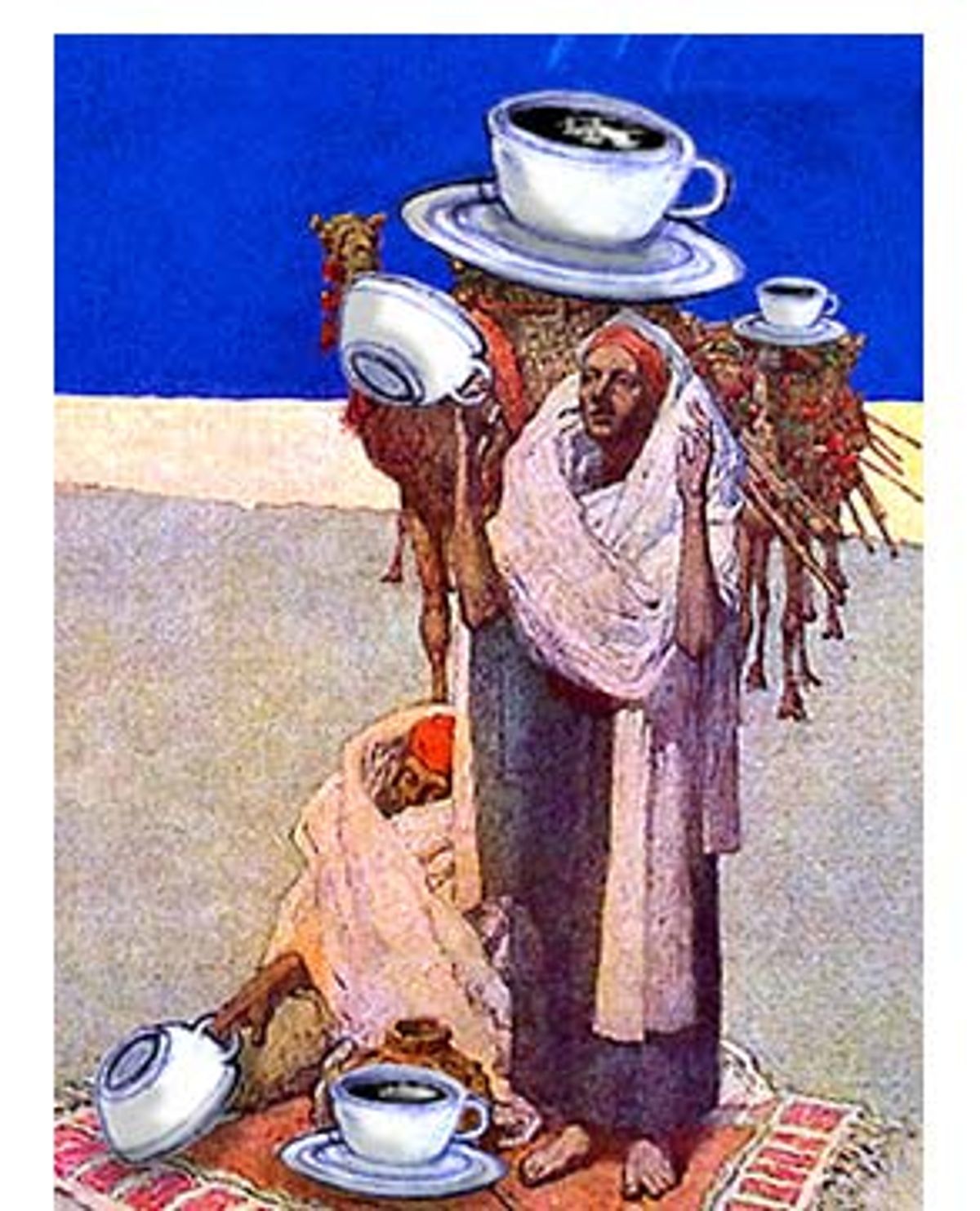

L is for latte

As you sip one of those wimpy, froufrou confections in Starbucks, think about this: Arabica. Yes, the humble coffee bean. First cultivated and brewed as rocket fuel by Yemeni tribesman way back when -- though it's disputed whether the beans were transplanted from Abyssinia (Ethiopia) to the Arabian Peninsula or whether it was the other way around. As an afterthought, we might not now have this plague of Starbucks and chi-chi cafes were it not for the Ottoman Turks, the Viennese getting the clever idea of the coffeehouse from them in the late 17th century.

M is for mosque

Funny, thinking about what Oriana Fallaci said earlier, the architectural flourish commonly attributed to the Moors, the curved arch, was actually copied from the Visigoths in Spain. Byzantine art and architecture, above all the Hagia Sophia in what was then Constantinople, had a profound influence on Islamic builders and artisans. However, it's the humble church steeple (via the mighty cathedral tower) that has an Islamic antecedent, the minaret.

N is for navigation

Without Arabian improvements upon the compass, the astrolabe, nautical maps and seaworthy lanterns, Magellan, Cabot, Vasco da Gama, Columbus, et al., might have had trouble pulling anchor and leaving port. The Arabs also pioneered the usage of hydraulic presses and water clocks, which tracked the passage of time and phases of the moon.

O is for optics

The concept of camera obscura, which is indispensable to the later development of photography, was first suggested in "The Treatise on Optics," by Hassan Ali Aitan (963-1009).

P is for paradise

Consider the varieties of roses -- the damask and the gallica, to name the two most common -- brought to Europe through Spain and Southern Italy by the Moor. Perhaps a rose is a rose is a rose, but what signifies here is where they're planted, and to Islamic sages and poets, gardens were symbolic of the paradise to come, a "blue green" paradise, blue for water, naturally, and green for greenery. The word "paradise" is of Persian origin ("paradaeza"); it literally means garden. Paradise as a garden or pleasure ground with swaying houris (heavenly handmaidens), the one that's promised to good male Muslims, figures heavily in the Quran, in contrast to Genesis where the Garden of Eden is a paradise lost. (And there are no houris in the Old Testament and definitely none in the New; is it any wonder Islam won so many converts?)

Q is for Qasim

Can you name the mystical Sufi poet who inspired Spiritual Girl Madonna to whirl like a dervish in "Speed of Light"? The one who is beloved by Demi Moore, quoted by Deepak Chopra and read by New Age ninnies from Beverly Hills to Notting Hill? (None of this, incidentally, should be held against him.) A Persian of Greek descent, who's up there in the Persian pantheon with Attar, Firdausi, Hafiz, Khayyam and Sadi? OK, OK, you know already: It's Jalad'din , but actually before him there was another, more carnal Rumi. Ibn al-Rumi (836-896) was an expansive, unforgettable, larger than life figure, Walt Whitman and Dylan Thomas rolled into one. He was magnificently ugly, unkempt and unwashed, pugnacious and ferociously sarcastic ("Those who kiss ass shouldn't complain of wind"), promiscuous, gluttonous, bibulous, blasphemous and irredeemably bohemian -- and he wondered why he couldn't get a position at court. And Qasim, you ask? He was the Caliph's vizier, who, fearful of the poet's wicked tongue, graciously poisoned him at supper. Rumi, though, had the last laugh. Upon quaffing the fatal potion and having a good burp, Rumi rose to leave. Qasim asked where he was off to, and Rumi replied he was going where the vizier had sent him. "In that case, convey my greetings to my father," Qasim said, thinking himself very witty. "I am not going to the fires of hell," Rumi replied. (Well, I needed something for Q.)

R is for religious tolerance and racial equality

Yes, hard as that might be for some to believe, Islam was the first major religion, certainly the first monotheistic one, to practice religious tolerance. Not that Muslim tribesmen didn't put to the sword those who refused to convert -- they committed their fair share of well-documented massacres early on -- but military success came so swiftly to them and on such a vast scale, that they found themselves burdened with an empire, and needed all the help they could get from their cleverer subjects to run it. They were, after all, warriors, not administrators. As rulers they were lenient, even generous (unlike the Germanic tribes that ravaged the late Roman Empire). Besides, Jews and Christians were "People of the Book" -- Islam borrowed much from its elders; Abraham, Moses and Christ are recognized prophets in the Koran -- and as long as they paid their tithe to the Caliph and kept out of trouble, they were free to do as they wished (the Zoroastrians in Persia were treated in similar fashion). "Holy Toledo," the meeting point of the three great religions, became a model of religious tolerance and harmony -- an idyll that ended when the Christian kings of the north recaptured it in 1085. (Until the rise of Holland in the 17th century, if you were Jewish it was generally better for your overall health and well-being to live in Muslim lands such as North Africa, the Levant or Turkey than almost anywhere in Christendom, particularly those places where Catholicism prevailed. French missionaries are to blame for introducing the virus of anti-Semitism to the Middle East in the 19th century.) Of the three great thinkers who flourished under Islamic rule, one was non-Muslim, Maimonides of Cordoba (1135-1204), author of "The Guide for the Perplexed," who was Jewish. Like Avicenna and his fellow Cordoban, Averroes, Maimonides attempted to reconcile Aristotelian philosophy with religious belief. He died in Alexandria, where he founded the great synagogue.

Regarding race, Islam is colorblind, which came as a surprise to Malcolm X on his pilgrimage to Mecca, where he found himself worshipping alongside blond-haired, blue-eyed white devils. Unlike Christianity, which justified racial slavery (blacks were inferior, less than human and so forth) by citing Ham in the Old Testament, Islam emphasized the equality of man before the eyes of God, whether black or white, rich or poor, man or woman. But, as we all know, what is preached isn't necessarily what is practiced. The cruel irony of Malcolm X's revelation, which challenged his ideas and changed the course of his life, was that he had it in a country that didn't abolish slavery until 1973. (Slavery exists today, despite claims to the contrary, in Mauritania and in the Sudan, both Muslim nations, the latter a fundamentalist state that has prosecuted a genocidal war against its southern, African half for more than 20 years. None of this, of course, was brought up at the United Nations conference on slavery in September.) And although the British, Dutch and Portuguese dominated the Atlantic slave trade in Caryl Philips' "Atlantic Sound," the Arabs held a firm whip hand in East Africa, built entire ports and cities devoted solely to that very profitable end, and played a significant role as middlemen throughout the continent. Still, it is good to know that Islam is colorblind.

S is for shatranj

Although modern chess originated in Northern India in the 7th century A.D., where it was called chaturanga, it was introduced to Spain and Sicily a century later by Moorish invaders and Saracen traders. Shatranj, which means "king's game" (shah tranj), differs slightly from the game we know today, in that instead of a queen there was a firzan, and in place of the bishop there was a fil (of course). The game was slower, with pawns allowed to advance but one square in the opening and no castling allowed. Victory came from checkmate (from the Persian, "Shah mat," the King is lost or helpless), stalemate or a "bare king" (the king alone, like Richard III at Bosworth Field). Some caliphs played "living chess" -- human pieces, slaves or prisoners -- the downside for the participants being possible decapitation if one was captured. As depicted by the Elizabethan playwright Christopher Marlowe, Tamburlaine -- in real life infamous for the Sack of Baghdad in which a million people died -- was fond of this pastime.

T is for turban

Let's face it, the turban, the burnoose, that wild and crazy Arafat thingy the college kids love to wear, whatever you wish to call it, is a brilliant fashion accessory. Imagine Edith Sitwell, Audrey Hepburn or David Hume without theirs; you can't, can you? With a little bit of water moistened about the inside you have a portable air conditioner. The turban was an early instance of form following function, though I have a feeling Sitwell, Hepburn and Hume were unaware of all this. Speaking of turbans, you need the right setting for one, too, something out of an odalisque by Ingres or Matisse: muslin, damask, chintz to cover sofas and pillows -- Moorish appurtenances on which to seat your little keester and to rest your weary head -- while being fanned by eunuchs, of course.

U is for university

The concept of the university originated with the madrassas, which were centers devoted to religious instruction, as they are in considerably less cosmopolitan forms in Muslim nations today. The first madrassas in Spain, in Malaga, Zaragoza and Cordoba, which later evolved into universities, started in the 11th century. The foundation of Damascus University dates back to the 8th century.

V is for venetian glass

Venetian glass blowers, famed for their miraculously intricate and delicate creations, learned their secrets from the Arabs (and went on to monopolize the glass trade for centuries). Islamic artisans and craftsmen, renowned for their ceramics, armory and masonry, made a deep impression on their Spanish, French and Italian counterparts. One could easily compose an alphabet of objects, decorative and otherwise, from Aubusson tapestries to the engravings on Zildjian cymbals, that bear traces of Arabic and Islamic design and calligraphy.

W is for watermelon

This is just one of the many crops the Arabs introduced to the West. Others include artichokes, rice, cotton, asparagus, oranges (from "naranj"), lemons, limes, figs, dates, spinach and eggplants. Arab methods of irrigation, which made the desert bloom, are still utilized today in North Africa and the Iberian Peninsula, as are the wells and aqueducts they built.

X is for Xenophon

Have you heard of him? Friend of Socrates and Plato, guest at the Symposium, author of a treatise on horses (the Hippike), Xenophon, in truth, was a bit of bore. Nevertheless, we're better off for knowing him because of the company he kept. Aristotle was a special favorite of Islamic scholars and thinkers such as Avicenna and Averroes, particularly for his "Ethics." Much of what remains of the Greek classics was salvaged, translated -- into classical Arabic, Hebrew, Latin, Persian and vernacular languages such as Castillian -- and interpreted under the aegis of the Arabs, with non-Muslims, anonymous scribes and great thinkers alike playing their parts (Maimonides comes to mind). Contrary to popular belief, it was Christian fanatics who sacked the Great Library of Alexandria (they followed up with a pogrom), decades before Muhammad was born.

Y is for the yearning one (el taleb)

Like Scotsmen and their kilts, there's more going on under those burqas than you might think. El taleb, or "the yearning one," is one of the 46 different kinds of vulvae described in the ninth chapter of the Arabian equivalent of "The Kama Sutra," "The Perfumed Garden of the Shaykh Nefzawi," translated by my favorite roaming Brit (a very short list, that), the randy Sir Richard Burton. "This vagina is met with in a few women only. With some it is natural; with others it becomes what it is by long abstinence. It is burning for a member, and having got one in its embrace, it refuses to part with it until its fire is completely extinguished"; talk about vagina monologues. (Note, fair ladies, there's a similar chapter on male equipment.) Other chapters deal with the act of generation, with praiseworthy men and women, with contemptible men and women, with positions other than the missionary (mullah position, anyone?), with arousal techniques, with impotence and sterility, with pregnancy, and so on and so forth. In contrast to the early Christians, the Arabs had a refreshing view of sex -- it was for pleasure, too, not just procreation.

Z is for zero

From "zefira," or cipher. Nought, nothing, nil. What a concept. Carried over from India to the West by the Arabs. Less than zero? Well, you're getting into negative numbers there ...

Shares