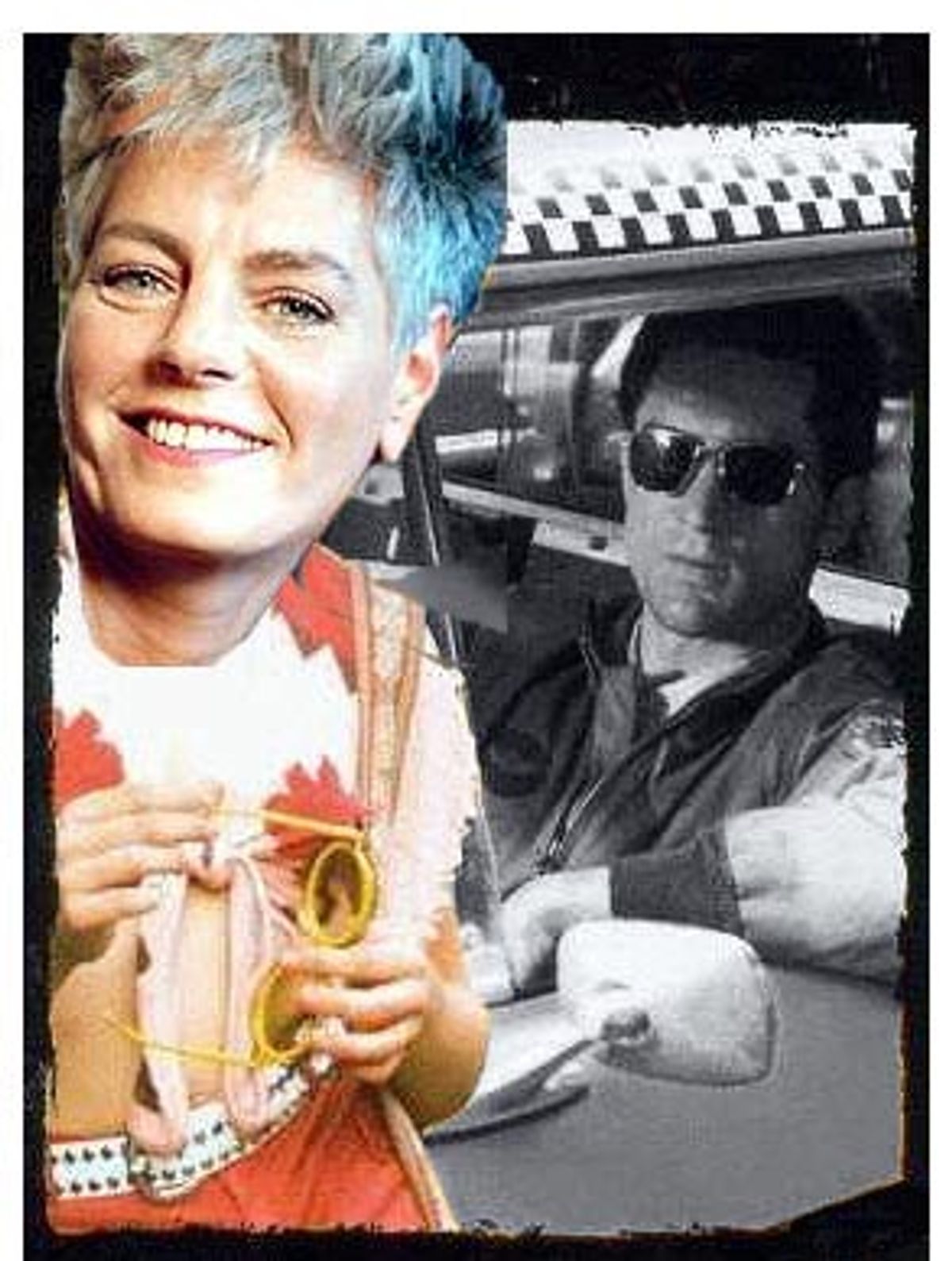

After River Phoenix took 11 fatal overdoses one Halloween in 1993, my editor sent me to tour the L.A. druggy underworld with Julia Phillips as my Virgil. Phillips, who died of cancer on Dec. 31 at age 57, had long since vanquished her coke problem, with the same iron will that won her an Oscar, forced Scorsese to cast De Niro not Keitel in "Taxi Driver" and enabled her to dynamite her bridges with her book "You'll Never Eat Lunch in This Town Again," which could've been called "Take This Oscar and Shove It." Phillips was, in my opinion, Hollywood's queen of the night, a scene who couldn't wait to happen, a talent magnet. Close encounters at her beach parties produced movies like "Close Encounters of the Third Kind."

The night I met her, in her "'70s room," festooned with artifacts such as the original "Close Encounters" photo streaked by the coke blowtorch she formerly kept permanently lit, and a snap of Scorsese in bell-bottoms so flared he resembled a melting candle ("What were we thinking?" he said later, his voice softening at the mention of Phillips' name), she was still in the sizzling center. She whipped up a superb home-cooked meal with fine wine and Pine Sol-like frozen Jaegermeister ("You have to take two shots; I won't give you any otherwise"), hopped into her sporty rig, and light-warped off to Babylon, a restaurant so hip it was unlisted, so that only stars could make reservations.

We hooked up with the aptly named trailblazing producer Kit Carson and his skinny new discoveries, two Dallas burger-flippers and professional car parkers, on their first night in Hollywood. (Now Wes Anderson and Owen Wilson are the co-authors of "The Royal Tenenbaums," the best movie of the new millennium.) Phillips wanted me to put them in a magazine to make them stars, not really to cash in on it herself -- she just liked to warm her hands with new flame. They were very much like Spielberg when she'd met him, back when Spielberg was a nerd in creased jeans, except that they idolized drug bard Gus Van Sant. Phillips was evangelical about the latest Tinseltown party favor, invented by her: Ecstasy soaked into a joint in a microwave. The Texans stepped outside at her behest; then she skipped back without them, laughing and clapping her hands. "I was a naughty girl! I made the boys throw up!"

"It was worse than that," Anderson told me later. "One of us collapsed into the dirt, just like River Phoenix."

They awoke with nothing worse than nasty headaches. "We really liked Julia, though," Anderson told me. I wrote up the incident with no names, but everyone knew it was Phillips, and somebody faxed the piece with sarcastic comments to Anderson's home office at his mom's place in Texas, and his mom gave him a royal lecture about falling in with fast company. Thanks, Mom! Like Spielberg, who (according to Phillips) barely inhaled at her beach parties, Anderson went further in the slow lane.

Phillips, however, was unfazed by the semihigh life. She could puff Ecstasy, down heroic cocktail after cocktail and still chat up a witty storm and drive like Mario Andretti -- no, like Steve Martin at the start of "L.A. Story" -- zipping crosstown via hair-raising shortcuts only the ultimate local would know, stopping with a rakish screech at the valet's feet and flipping him the keys with the aplomb of Top Cat. Infamously, in L.A., the center cannot hold because there is no center, but everywhere I went with Phillips seemed to be the center: the No. 1 record producer feting the cool-du-jour ingénue, the power moshers who never let their hair get mussed.

After much club-hopping and no sleep, Phillips wanted to go dancing with what she termed "the cliterati" at Girl Bar. But I had previous engagements. So I bid farewell to Phillips and proceeded to risk getting shot taking my photographer to a crack house, tried but failed to wangle an invite to a clothing-not-optional "underwear party" (where would I put my tape recorder?) and trolled for quotes at Club Lust, formerly Club Fuck, where the dripping Whipping Room had been converted to the more huggable Pillow Room under the influence of (not yet microwaved) Ecstasy and police pressure to tone down the S&M.

The kids seemed more out of control to me than Phillips was: They considered an organic arugula diet by day the antidote to narcotics by night, and to a person, they denied having any drug problem. They never used heroin -- only on weekends, and they never smoked from a tinfoil pipe, because that shit gives you Alzheimer's! I asked a girl named Bunny, whose breasts erupted from a leopard-skin top tucked into spray-on pants, if she was a member of the Hollywood drug scene. "Oh, I took a few Valium an hour ago," she said, slurping from a birdbath-size beer.

"How many milligrams?"

She looked at me like this was the most irrelevant question she had ever heard. "I don't know. They had V-shaped holes in the middle." (By contrast, Phillips recalled precisely what she took on Oscar night in 1974: three Valiums, one upper, one and a half drinks, two joints and a dash of cocaine.) I asked Bunny if she had a job.

"Oh, yes, a wonderful job!" Doing what?

"Well," she beamed, "it's illegal!"

Julia Phillips was illegal, but she wasn't such a bad influence, I think. She was a fighting pop-culture priestess who could talk to the young. Compare her with John Lennon in his Harry Nilsson-led L.A. "lost weekend" phase: Those guys were trying to feed off a youth scene in a negative way. There was still, in the '90s, a sign up at a Sunset club: "Hollywood Vampires Club," with Lennon, Nilsson, Ringo and Alice Cooper as president, V.P., secretary, etc. When they got plowed with McCartney and recorded some oldies, they were so uncreative they couldn't play "Chain Gang" in time or in tune. They invited Stevie Wonder to sit in -- he was recording his masterpieces down the hall -- and he politely excused himself as soon as he could, then yelled at the producer, "Those guys were terrible! Embarrassing! Get me out of this!" When Nilsson urged McCartney to try PCP, McCartney asked, "Is it fun?" Nilsson thought and said, "No." Phillips would never try to convince anyone to do anything she didn't find fun, and she cherished the ideal of artistic excellence.

And she wasn't a nihilist like Nilsson. She optioned "Interview With a Vampire" (a job her indiscreet book kiboshed), but she wasn't a Hollywood vampire. She genuinely, and far less self-interestedly than most, wanted to help propel young talent to the empyrean. She nurtured people (and by insider accounts, once free of addiction, she was a devoted mother). The energy most entertainment types pour into sexual predation she poured into hepcat cafi society. (When she ushered me into her '70s room, off her bedroom, she informed me, "I'm not gonna fuck you.") She wanted to get the cool kids to brew risky new ideas -- and not just about Ecstasy soaked into a joint.

She yearned to be surrounded at all times by a cozy countercultural salon, a party that served as a comfort zone. That's why she conducted meetings in her old drug room -- it wasn't a place of bad memories, even though it nearly killed her. It was a place of bonding, exploring, achieving -- where everybody could get creative and fulfill their dreams, no matter how outrageous, with Phillips helping out by threatening to cut some craven suit's MBA balls off and sew them into his throat if he tried to interfere with the "genius work" her pals were putting down.

Only some of Phillips' work was genius, however. It was not all to the good that she was the anti-Spielberg -- surfing the edge of control instead of being cautiously methodical, given to the intuitive leap rather than the encyclopedic cinematic erudition and calculated moves of a past master. She pissed away much brilliance in the performance art of aleatoric storytelling, like a less cruel Courtney Love. (Not that Phillips was always nice or fair: She notoriously accused Goldie Hawn of odoriferous poor personal hygiene, and I can testify that when Hawn unexpectedly kissed my cheek during an interview, she smelled like a daisy. Besides, was Phillips' nose, caked with $120,000 worth of coke, really the ideal instrument to trigger Proustian feats of accurate olfactory reminiscence?)

Even her best work, the mordant, merciless "You'll Never Eat Lunch in This Town Again," which outdid Capote in shrieking truth to decadent power, failed to be what it could have been if she had only had more focus and developed the sketchy, skeletal reminiscences into shaped narratives, and made the kind of connections that make Peter Biskind's "Easy Riders, Raging Bulls" a lasting work of literature.

Her second book was an aimless, navel-gazing suckathon. She didn't have enough leftover dish, and she evidently wouldn't let her ego get out of the way enough to let her friends advise her to rewrite it from top to bottom. She should've trusted her brain trust -- or maybe she did, but nobody else in Hollywood dares to risk a friendship by telling harsh truths. The place lives by and for beautiful lies. She was scared as well as daring, and movie people can smell fear better than piranhas. Even though she conquered hard drugs, and appeared clearheaded even while mildly stoned, to some extent the party had to get the better of the art, and did. It happens all the time: Critic John Lahr claims chronic pot is the reason Paul McCartney's post-Beatles music is "spun from rotten satin." Like George Harrison and Linda McCartney, Phillips ducked the scary drugs and died from the Reaper's stealth weapon, cigarettes.

But while she lived, few lived with more gusto or less reverence. I remember the message she left for me at the Chateau Marmont: "Come on, let's go dancing, everybody will be there. It'll be fun!" No doubt it was fun, and Julia Phillips made it more so.

Shares