In 1972, there was nothing on the planet as unhip as country music.

Trippy artists such as the Grateful Dead were "Truckin'" to banjos in California, but the music of the South, by the South and for the South was about maintaining the status quo -- with shotgun authority. Country music stars loved God, Mama, the flag and pork sausage. They were pro-Nixon and pro-war. As Merle Haggard reminded us, they didn't smoke marijuana in Muskogee or take their trips on LSD. Country fans were equally conservative, protectors of a Waltons version of America invented during the Depression and cemented in the paranoia and prosperity of the Cold War. Southern children were supposed to mind their parents, dress nice for church, and go to work at Daddy's car dealership when they graduated from high school.

Like arrogant Custers, most Nashville music execs were oblivious to anything that was happening on the mammoth rock scene just over the generational horizon. In reality, lots of Southern teenagers and college students were smoking dope in the back of the family's Impala on Saturday night, then spraying it down with Lysol so the smell wouldn't be there on the trip to Sunday school the next morning. But the good ol' boys who ran Music Row adjusted their white belts and dismissed the counterculture as some kind of evil beast seducing America's youth to an altar call of sex, drugs and (even worse) long hair. The Nashville establishment was recording tunes such as Donna Fargo's "Happiest Girl in the Whole U.S.A.": "Shine on me sunshine/ Walk with me world/ It's a zippy-dee doodah day."

That's why "Will the Circle Be Unbroken" was so utterly weird when it arrived in music stores that October. It's also why, on its rerelease 30 years later, it remains one of country music's most richly authentic and significant albums.

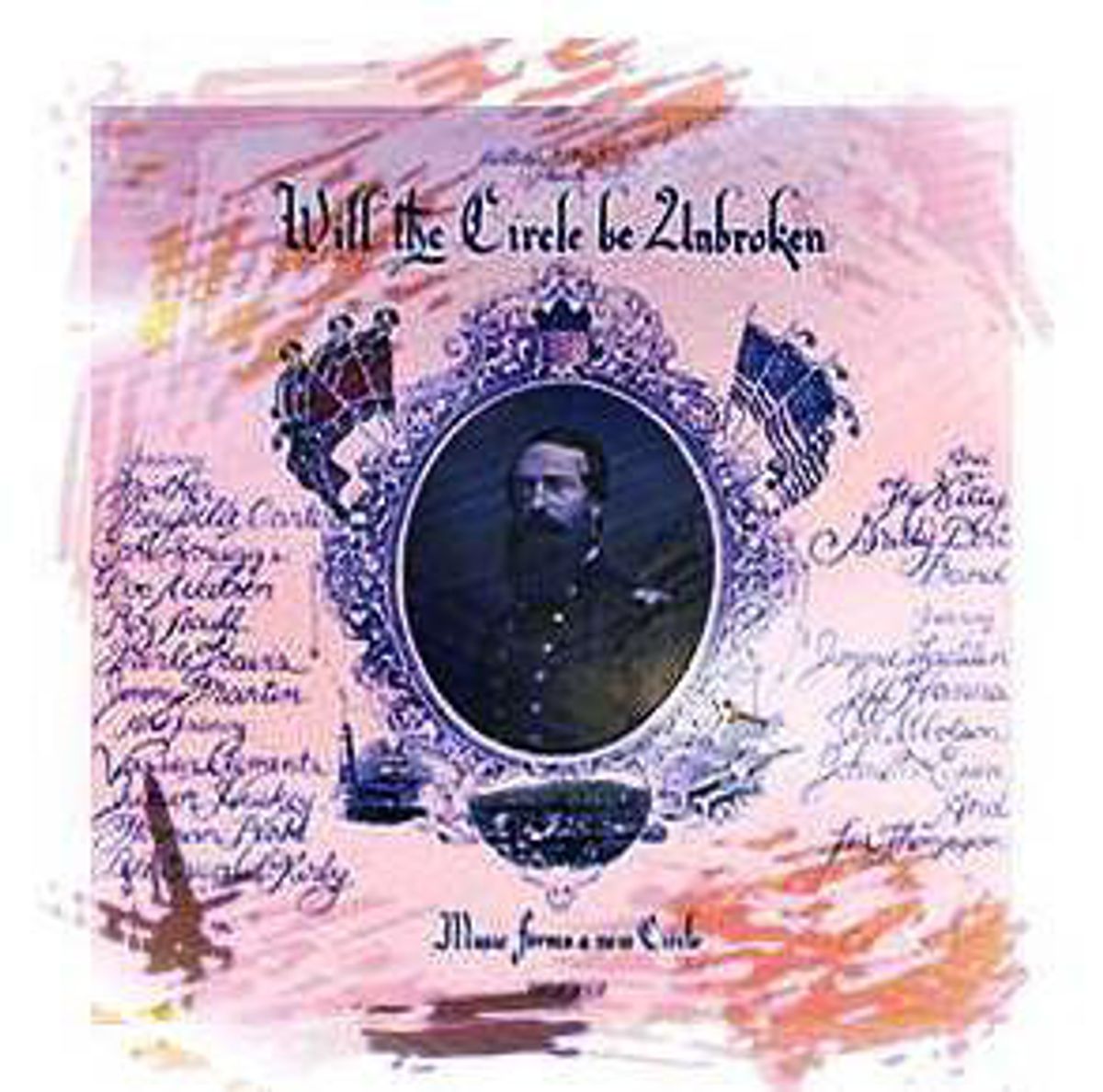

Lined up on display racks next to LPs with hippie-mystic covers, such as "Led Zeppelin IV" or the Moody Blues' bombastic "Days of Future Past," the three-record set looked like something off the wall of a Cracker Barrel restaurant. A stiff portrait of a Civil War officer stared out from the front, surrounded by battle flags and artists' names scrawled out in beautiful 19th-century penmanship. The album was officially by the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band, a shaggy group of West Coast musicians who had a Top 10 pop hit in 1971 with the sentimental vaudeville ballad "Mr. Bojangles." The rest of the acts on the album were people most baby boomers outside the South had never heard of: wailing mountain singer Roy Acuff, Mother Maybelle Carter (of the legendary Carter family), banjo innovator Earl Scruggs, guitarists Doc Watson and Merle Travis, and bluegrass king Jimmy Martin. Below the Mason-Dixon line, the musicians were known, but mostly considered old geezers by young people trying desperately to escape the Saturday-afternoon dreariness of "The Porter Wagoner Show" for something cool, like "Where the Action Is."

By 1972, these salt-of-the-earth artists had largely been edited out of the commercial country music scene. To a Southern population trying desperately to climb its way from the outhouse into kitchens lined with new appliances, they were uncomfortable reminders of a not-so-distant hillbilly past. Unsophisticated. Tacky. Too hick. The arrival of "Circle," and its eclectic collection of original bluegrass artists -- the folks who actually invented much of the genre -- was like having Cousin Woodrow show up for dinner and stuff his napkin under his collar. Music Row looked askance. Radio didn't touch it.

What the Dirt Band knew (and we were soon to learn) was that the elder acts on "Will the Circle Be Unbroken" were our forgotten birthright, the authenticity the youth culture seemed to be so desperately seeking at the time. With their Brylcreem hair, short-sleeved dress shirts and ties, these traditional music icons were as back-to-the-garden as granola and cotton skirts made in India.

As a result, "Circle" became bluegrass music's first million-selling album. In an era where more people knew what patchouli smelled like than a smokehouse, it turned out to be a watershed moment for country music as thousands of suburban teenagers and college students stacked the three records on their turntables and were converted to bluegrass. As "O Brother, Where Art Thou?" would do 30 years later, it introduced a new generation to the genre.

Recorded live on two tracks at Nashville's Woodland Studios, "Circle" sounds like an intimate picking session on the front porch after supper. It's also as close to the earthy roots of country music as any commercial recording has ever gotten before or since. ("O Brother, Where Art Thou?" only occasionally comes this close).

Producer William McEuen let the tape roll as the members of the Dirt Band chat, swap stories and coax their idols to sing and run their fingers over acoustic instruments with a spontaneous joy and virtuosity that had largely been abandoned by Top 40 country. Fiddles cry. Dobros wail. There's the click-clack sound of finger picks on a washboard. Jaunty banjos race around 37 traditional mountain tunes that breathed new life into ancient melodies: "Tennessee Stud," "Soldier's Joy," "I Saw the Light" and the A.P. Carter song that has become country music's mantra (it's actually carved in stone in the atrium of the new Country Music Hall of Fame & Museum), "Will the Circle Be Unbroken."

In accents as country as a baying hound dog, the veterans casually -- and sometimes skeptically -- chat with the Dirt Band about their craft. "Pick the banjer solid, John. You've picked one for 15 years, ain't ya?," Jimmy Martin says, tossing out a challenge to bushy-haired John McEuen on how to kick off the made-for-clogging opener, "Grand Ole Opry Song."

Acuff, sounding like a crusty church deacon, says, "I believe it's true: Whenever you once decide you're going to record a number, put everything you got into it. So let's do it the first time -- and to hell with the rest of it."

Blind North Carolina flat picker Doc Watson (whose college-circuit career was launched by this album) hears the Dirt Band's Jimmie Fadden saw on a harmonica, then coaches him: "That's a horse's foot in gravel, man, that ain't trains. Runnin' through a fordin' creek." Then you can close your eyes and hear the Tennessee Stud race across the Rio Grande into Mexico, Watson's hands tapping on the hollow guitar as if he were plucking your eardrums.

Throughout the sessions, the Dirt Band -- McEuen, Fadden, Jeff Hanna and Jim Ibbotson -- seem to drink it all in like starstruck students at the foot of Socrates. Perhaps it was their wide-eyed worship that pulled such brilliant performances out of the aging entertainers. Ironically, when the album was recorded, most of the country artists on "Circle" didn't know who the heck the Dirt Band was.

When the group arrived in Nashville in August of 1971, they looked more like a bunch of guys likely to be run out of town in a flashing patrol car. Coming from the California jug-band scene, the group's mellow members wore clothes straight out of a giveaway bag -- nubby flannel shirts, torn jeans, mismatched socks. They sported untamed beards and mustaches, grown in the shaggy anti-establishment mood of the West Coast. In a time when Southerners judged each other by how high hair was piled up on their heads, these guys looked like they hadn't been to a barber since grade school.

So it's no surprise that the conservative country music community thought it a bit sketchy when the Dirt Band made its proposal: Come make an album with us. The father of bluegrass, Bill Monroe, flat out said no way. Acuff called them a bunch of longhaired boys. It seems kind of quaint now, but when the album came out, as much was written about this clash of cultures as the music they made together.

Looking back on the recording, "Circle" has survived the transience of fashion, political views and class distinctions and all that goofy, dated press about hippies and long hair. Many of the legendary stylists featured on the album are dead now (Roy Acuff, Mother Maybelle). The members of the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band are way on the backside of middle age. You're now more likely to see their shaggy 1972 hairstyles on truck drivers than on college kids. And the soundtrack to "O Brother, Where Art Thou?" fueled by a rubber-faced actor (George Clooney) and the fictional Soggy Bottom Boys, has surpassed "Circle" in sales and awards.

Yet when it comes to originality and pure musical craftsmanship, "Will the Circle Be Unbroken" is every bit as vibrant as when it was recorded in 1971. It leaps across space and time to seduce even the most urbane listener to enjoy heartfelt mountain music created in the souls of ordinary folks. It's country music at its best: intimate, uncontrived and joyous. Hand me that washboard, will you, son?

Shares