Now that federal prosecutors have secured a guilty verdict against accounting firm Arthur Andersen for shredding crucial documents related to Enron's finances, the Department of Justice is expected to turn its attention to Enron, with possible indictments against former executives coming soon for violating federal fraud statutes.

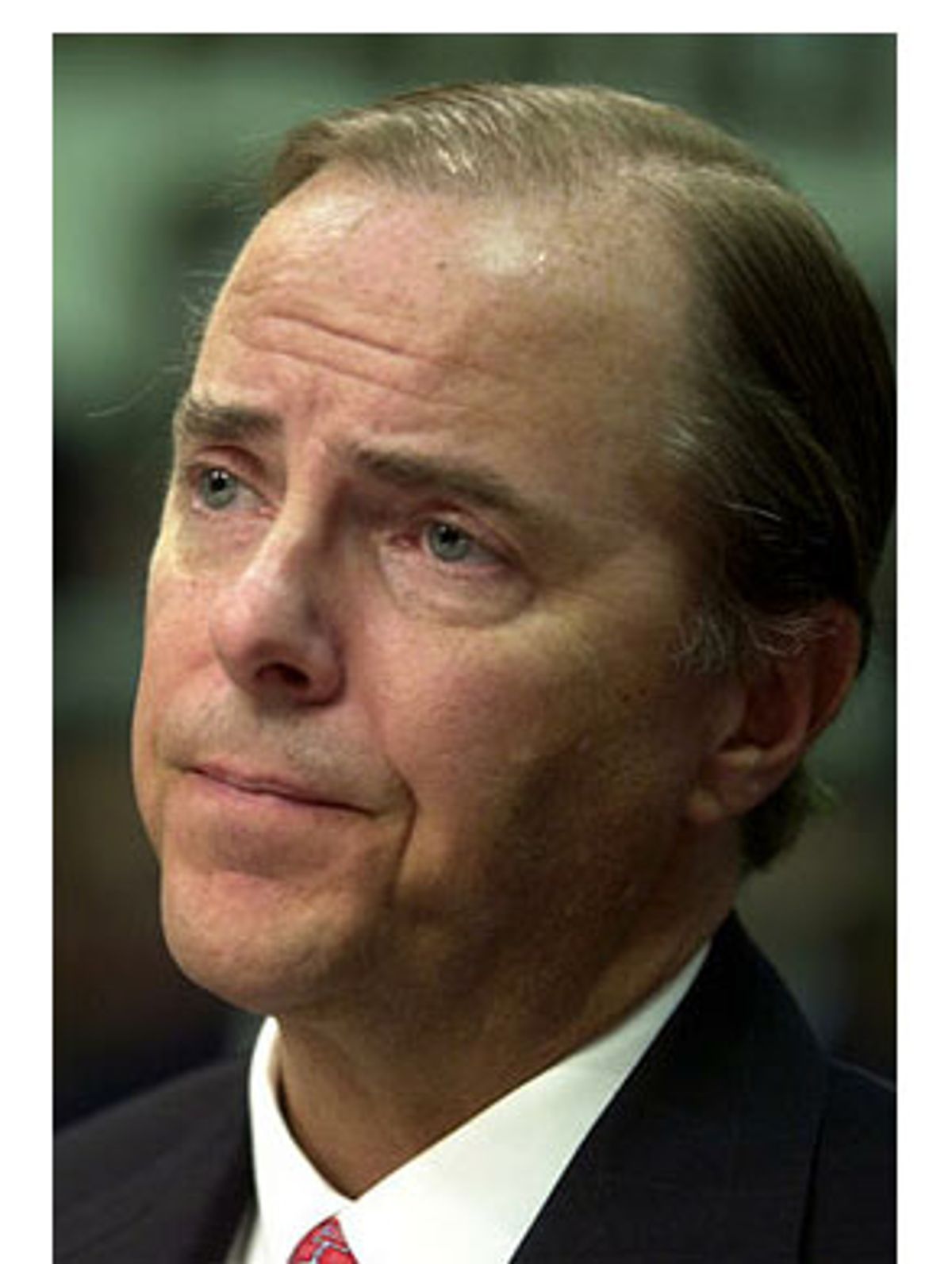

According to sources close to the Justice Department's probe, former Enron president Jeffrey Skilling is facing particular scrutiny. And Exhibit A against him could be testimony he gave before Congress in February, when he claimed he knew little about one of Enron's byzantine partnerships.

"Congressman, Enron Corporation was an enormous corporation. Could I have known everything going on everywhere in the company? I had to rely on the best people. We hired the best people. We had excellent, excellent outside accountants and law firms that worked with us to ensure," Skilling testified. "At no time did I enter into any transaction or was I personally involved in any transaction that I believed was not fully in the interest of Enron shareholders."

But that does not appear to be entirely true. Especially considering his close relationship to one particular partnership named after the furry but ferocious "Star Wars" character, Chewbacca.

Chewco accounted for two-thirds of Enron's losses over a four-year period beginning in 1997. It is one of the complex partnerships that Enron employed to keep billions of dollars of debt off its books, boosting its profits and credit level along the way. Enron executives participated in these partnerships and earned millions of dollars, which has now raised major conflict-of-interest issues being investigated by Congress. The legality of Chewco remains central to the examination of Enron and its bankruptcy. Joseph Bernardino, the CEO of Enron's auditor, Arthur Andersen, testified before Congress in December that Chewco's creation may have been illegal because it lacked the required 3 percent interest from an independent third party necessary for it to be treated as a separate company and not an Enron subsidiary.

Federal investigators say they are interested in finding out who knew about Chewco, what they knew about its financial structure and when they knew it. Anyone who knew that Chewco didn't qualify as an independent entity but allowed it to be treated as such might have violated federal fraud statutes, the investigators say. But in interviews with me (while I was at the Dow Jones Newswire), with the New York Times and with the Houston Chronicle in December, Skilling said he did not know the details of Chewco's financial structure.

However, according to the minutes of a Nov. 5, 1997, meeting of Enron's board of directors, which Skilling took part in via telephone conference call, the one-time president of the country's sixth-largest corporation appeared to know much about Chewco from the moment it was being established.

At the board meeting, Skilling instructed his protégé, former Enron chief financial officer Andrew Fastow, to discuss Chewco. "Mr. Skilling explained the background of the joint-venture by an affiliate of the company and the California Public Employees Retirement System [CalPERS] in Joint Energy Development Investments Limited Partnership," the board minutes state. "He called upon Mr. Fastow to discuss the recommended action. Mr. Fastow referred the committee members to the material for the meeting, a copy of which is filed with the records of the meeting. He explained that Chewco Investments LLC, a special purpose vehicle not affiliated with the company or CalPERS, would acquire the 50 percent interest owned by CalPERS in JEDI for $383 million. He stated that a corporate guaranty of a $383 million bridge loan and a corporate guaranty of a $250 million loan to Chewco would be required. He reviewed the economics of the project, the financing arrangements and the corporate structure of the acquiring company. He recommended that the committee approve the corporate guaranties associated with the transaction."

A discussion of Chewco followed, details of which were not included in the minutes, and the board then approved the creation of Chewco.

Furthermore, sources close to the Justice Department's probe of Enron told Salon that former Enron treasurer Ben Glisan, who was responsible for Chewco's accounting matters, is cooperating with the federal government and is providing details about Skilling's role in getting Enron's board to approve Chewco. Glisan and his attorney could not be reached for comment.

Congress, in its months-long probe of Enron, questioned Skilling in February specifically about Chewco, but only briefly. At the time, the congressional panel was only interested in learning whether Skilling knew that a former Enron employee managed the Chewco partnership, which would have been a violation of Enron's code of ethics. Skilling said he did not.

But had Congress fully understood the importance of Chewco, and that it was created to purchase the interest in another partnership Enron entered into with the California Public Employees Retirement System in 1993, then Congress also would have learned that Skilling had much to gain financially from Chewco's creation.

In September 1997, Skilling and Fastow paid a visit to Sacramento, Calif., to pitch CalPERS on a $1 billion joint venture known as Joint Energy Development Investments II, or, following the "Star Wars" theme, JEDI II. The partnership would invest in broad energy projects around the globe.

CalPERS was already invested in a similar partnership, JEDI I, which Enron and CalPERS started in 1993 with $500 million. But JEDI I was limited to investing in natural gas projects, whereas JEDI II would have its pick of energy projects, from oil to fuel cells.

"JEDI II was a better opportunity investment-wise for CalPERS," said CalPERS spokesman Brad Pacheco. "Skilling met with members of our board in September to discuss the idea." However, there was a catch. CalPERS would only invest in JEDI II if Enron found a buyer for CalPERS' 50 percent interest in JEDI I, which at this point was valued at $383 million.

Fastow spent six weeks attempting to find an investor for JEDI I, sources close to Fastow said, but there were no takers. So Fastow pitched the idea of Chewco to Skilling, and Skilling told Fastow "to make it happen," according to sources close to Fastow.

Bruce Hiler, Skilling's attorney, said his client believed that the assets in JEDI I were very valuable and that there were plenty of outside parties ready to invest in JEDI I, but ultimately Fastow came up with the structure for Chewco and that Skilling was "totally unaware" of the financial structure of the partnership.

"My client believed there were people ready to invest in JEDI I," Hiler said. "These assets were very valuable. He thought that Chewco was a totally legitimate entity because that's what he was told by Fastow."

Gordon Andrew, a spokesman for Fastow, declined to comment.

Skilling spent the next two months speaking with CalPERS about the JEDI II partnership, assuring the pension fund that Enron would find an investor to purchase CalPERS' interest in JEDI I, Pacheco said.

In October, Fastow worked on Chewco's financial structure. The partnership was made up of Enron executives and some undisclosed outside investors. But Chewco didn't have the $383 million to purchase CalPERS' interest in JEDI I. So Enron lent Chewco $132 million and guaranteed a $240 million loan, all of which Skilling was fully aware of, according to people close to Fastow.

But there was still the matter of an additional $11.5 million for Chewco to come up with. It was an important number, because it was more than 3 percent of Chewco's capital and if it had been invested by an outside source, it would have allowed Enron to keep Chewco off its balance sheet. However, Enron provided collateral for about half of Chewco's $11.5 million investment, meaning it fell far short of the 3 percent requirement to be considered an independent entity. JEDI and Chewco should have been included on Enron's books. By keeping the partnership off Enron's balance sheet, the company inflated its profits by $396 million over the next three years.

Now, with Enron's executive committee approving the Chewco transaction, Skilling went back to CalPERS, Pacheco said, and told the investment committee that Enron had found an investor to buy its share in JEDI I.

"We had no idea that it was Chewco," said Pat Macht, head of CalPERS public affairs.

The following month, on Dec. 15, 1997, Skilling made a final presentation to CalPERS in Sacramento about the JEDI II joint venture and promised the pension fund a huge return on its investment. The CalPERS board voted and approved the fund's investment in JEDI II.

And on Dec. 30, the financing for Chewco closed.

"Greed," said one Justice Department official. "It was all about lining Jeff Skilling's pockets."

It appears that Skilling had a lot to gain from CalPERS' investment in JEDI II. He held a 5 percent "phantom" equity stake in Enron Energy Services, an Enron spinoff that JEDI II invested in, according to a March 1997 Enron proxy statement. Phantom equity is used as incentive, primarily by small- and moderately sized and non-publicly traded businesses, to reward executives for helping to make a business grow.

EES was Enron's then-newly formed retail-energy unit, and it was struggling to sign up small business and residential consumers to electricity services. Just weeks after Skilling sold CalPERS on forming JEDI II, the pension fund and the Ontario Teacher's Pension Plan invested a total of $130 million in EES, according to an Enron news release at the time.

CalPERS' investment in EES was done through JEDI II, and the Ontario fund invested in EES directly. The investments gave CalPERS and Ontario a combined 7 percent stake in EES. Enron then valued the company at $1.9 billion, based on that investment and forecasts of future business.

With the $1.9 billion estimate, Skilling's 5 percent phantom equity was worth an estimated $100 million, according to Enron financial documents.

Enron booked a profit for EES based on the pension-fund investment at a time when EES still hadn't secured any new business. Skilling did disclose his 5 percent stake in EES to CalPERS prior to the pension fund agreeing to invest in JEDI II, Macht said, and CalPERS did not view it as a conflict of interest.

Skilling's lawyer, Hiler, said Enron converted Skilling's 5 percent phantom equity in EES into Enron common shares shortly after the investments in EES by CalPERS and Ontario. But Skilling decided not to take the entire $100 million and instead settled on $33 million because he wanted to reinvest in Enron, Hiler said.

Enron kept Chewco's activities off its balance sheet through last March, when Enron bought Chewco. The transactions with Chewco and other partnerships led in part to the $1.2 billion reduction in shareholder equity in October that was the start of Enron's undoing. But by that time Skilling, who had resigned from the company Aug. 14, was long gone.

Shares