Just when I thought there could be no further desecration of those who perished on Sept. 11, George W. Bush appoints Henry Kissinger to direct an investigation of the government's failure to prevent the terrorist attacks. Honestly, it took my breath away. Even in a time of cynical politics, this is stunning.

I realize, of course, that Bush never wanted any kind of independent investigation to take place -- that the families of the victims compelled him to act. And if the administration's goal is to contain and limit the probe, to avoid embarrassing revelations about U.S. intelligence failures, then Kissinger is just the man.

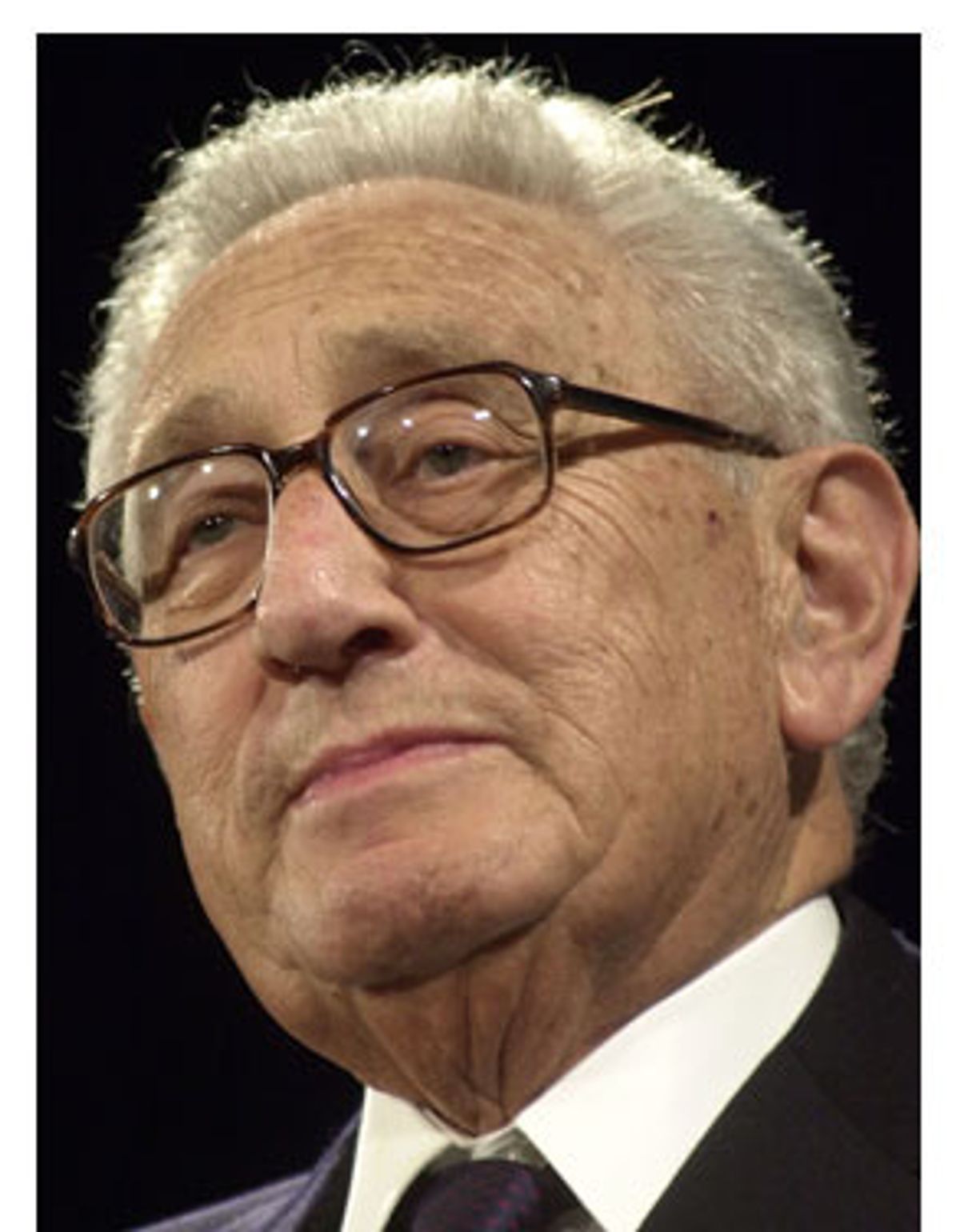

Forget Karl Rove. This is our true Machiavelli, a statesman famous for conducting foreign policy with a twist of treachery and deceit. From the clandestine bombing of Cambodia to supporting Pinochet's bloody military coup in Chile, Kissinger is a man who has many secrets of his own to hide. Talk about a conflict of interest! How can Kissinger, at age 79, a lifelong member of the national security establishment, a presidential advisor who wiretapped his own colleagues to prevent leaks, suddenly become a truly independent investigator of the CIA, FBI and the White House? Who would ever believe him?

There are those who argue that Kissinger, the Cold Warrior who went to China, can surprise us once again, crowning his career and salvaging his reputation, by transforming himself into a steadfast inquisitor of his old associates, friends and patrons. "He's working for his historic reputation now," argues William Safire, the former Nixon speechwriter.

Call me dubious. Kissinger is too compromised, too feeble, too solicitous of power to name names and reveal any uncomfortable truths about what the government ought to have done to forestall the Sept. 11 attacks. My own experience with Kissinger only deepens my skepticism about his credibility and his willingness to reform a flawed system.

I met Kissinger last year in New York to interview him for a public television documentary I am making about the Vietnam War and the protests it provoked. When I arrived with my camera crew at his Park Avenue business address, I noticed that his consulting firm, Kissinger Associates, was discreetly missing from the lobby directory. Even prior to Sept. 11, the former national security advisor and secretary of state was cautious about his own security. There's no telling who might show up. In Paris last year the French police arrived at his Ritz Hotel suite to serve Kissinger with a summons to appear in court to answer questions about French citizens who disappeared during the U.S.-backed coup in Chile. Kissinger immediately fled the country.

On the 26th floor we were buzzed into his office suite, questioned by a receptionist seated behind a transparent barrier, and finally admitted to a waiting room decorated in a Chinese motif.

I heard him before I saw him. In his unmistakable German accent, Kissinger was berating a female assistant for scheduling him at an event he did not wish to attend. Kissinger's tantrums were legendary at the Nixon White House. Here I would call his tone aggrieved and imperious, except that the more he complained, the more he sounded like a grumpy old man.

Suddenly he appeared at the doorway. "What's this about?" he growled, as if I were an unannounced intruder. I was momentarily dazed by the shock of recognition. "Oh, my god, it's Henry Kissinger!" I thought. It was like turning a corner and bumping into the ghost of Richard Nixon or John Mitchell. An imposing figure who cast a shadow over my draft age years. And yet, something was wrong. This wasn't the same Kissinger who prolonged the Vietnam War, lied about it, and haunted my youthful dreams. This was Kissinger diminished. An old man, recovering from surgery, shorter than I'd imagined, hard of hearing.

He motioned me into his office, closed the door and ordered me to sit on a couch to his left, explaining that he had a new "disability" -- a bad right eye. "What questions are you going to ask?" he demanded. Before I could answer he told me any mention of his being a "war criminal" was off-limits.

"If you are going to ask whether I feel guilty about Vietnam, the interview is over. I'll walk out."

Now I was nervous that Kissinger would bolt. I played my best card. I told him I had just interviewed Robert McNamara in Washington. That got his attention. He stopped badgering me, and then he did an extraordinary thing. He began to cry.

But no, not real tears. Before my eyes, Henry Kissinger was acting.

"Boohoo, boohoo," Kissinger said, pretending to cry and rub his eyes. "He's still beating his breast, right? Still feeling guilty." He spoke in a mocking, singsong voice and patted his heart for emphasis.

It was an astonishing moment. I longed for a camera. It may have been bad acting, but it was riveting.

I finally managed to stammer that yes, McNamara did express regret about the war. But Kissinger cut me off. Apparently we were not going to dwell on the former defense secretary's bleeding heart.

In fact, McNamara, another old man, an architect of the Vietnam War, had told me, "The war could have been avoided." He said his "greatest regret" was urging President Lyndon Johnson in 1965 to commit American troops to a land war in Asia. McNamara called the war a "tragedy."

"It tore the nation apart," McNamara said. "And I think to some degree we're still suffering from that."

McNamara's sorrow seems genuine. The infuriating part is that he still defends his decision to keep silent in public about his disenchantment with the war until long after it was over. "It's not appropriate for a secretary of defense to, in your terms, go public," he admonished me. "I felt that I could do more inside than I could have outside."

But McNamara's public reticence deprived the antiwar movement of a powerful voice and undoubtedly prolonged the war. In November 1967, one month after more than 50,000 Americans surrounded the Pentagon, McNamara submitted a private memo to Johnson declaring that the U.S. could not win the war and should withdraw from Vietnam. LBJ was not persuaded, McNamara departed. But he never bothered to tell Americans of his dissent until it was too late.

I still consider McNamara's failure in the late '60s to speak openly about the war unforgivable. He had championed the war, dispatched some 500,000 U.S. soldiers to fight it, and then neglected to mention he'd been wrong after all. But at least, late in his life, McNamara is taking some measure of responsibility and admits some of his mistakes.

Which is more than you can say for Henry Kissinger. On America's war in Vietnam -- which he inherited from McNamara and the Democrats but continued for seven more years -- Kissinger remains unreconstructed, unapologetic. He expresses nothing but contempt for McNamara's anguished reappraisals.

For several minutes, Kissinger continued to hector me about my intentions, wanting to know precisely what questions I would ask. I declined as a matter of journalistic principle. I felt the interview slipping away, his irritability increasing, and then abruptly, he agreed to go on camera.

Under the lights, even our softest lights, he complained. His right eye was clearly bothering him. His answers to my first questions were curt, stiff, cautious. But I avoided the phrase "war criminal," and after a while he settled into his standard defensive posture: speaking in that ponderous, suffocating drone that implies great meaning while revealing nothing.

As we changed tape, he snapped to life. "Good questions," he said, which meant I hadn't laid a glove on him. Then doubt crossed his face. "It depends on how you edit this." And just as quickly, his confidence revived. "No, you can't make this look bad no matter how you edit it."

His legendary arrogance and insecurity alternated throughout the remainder of the interview. But he grew testy as I probed. He defended the U.S. invasion of Cambodia in 1970, saying, "I personally believe we should have gone in deeper and we should have stayed longer," and he dismissed any possibility that the relentless U.S. bombing of Cambodia led to the disintegration of civil society and the rise of the genocidal Khmer Rouge.

"We could have won the war in Cambodia, which was possible," he argued. "Vietnam was questionable."

Asked why he did not push to end the war after he realized it was unwinnable, Kissinger groaned. "Could it have ended a year earlier, six months earlier? How do I know?" he shrugged. "I don't think so. Besides, by that time our casualties had gotten down so low that that was not a major factor in the situation."

Perhaps not for Kissinger or Nixon, but those casualties surely mattered to the thousands of Americans who died needlessly in the waning years of the war, not to mention the Vietnamese, Cambodians and Laotians who continued to die as Nixon and Kissinger pursued "peace with honor."

When Kissinger's associate, Daniel Ellsberg, gave the Pentagon Papers -- the government's secret history of the Vietnam War -- to the New York Times, Kissinger went ballistic. He was deeply involved in the Nixon administration's vendetta against the whistleblower. (And this is the man President Bush is now relying on to draw out truth-tellers from government agencies.) But he deflected my question about his campaign to destroy Ellsberg's career and reputation, saying only, "Ellsberg is one of the brightest people I have ever met."

Displaying his notorious thin skin, Kissinger interrupted me if I questioned anything he said. He asked me why we were still debating these matters 30 years after the war ended and then erupted at his opponents. "They present the history of the Vietnam War as if a bunch of power-crazed maniacs, first in the Johnson administration and then in the Nixon administration, who love to kill people, continued a senseless war, which the moral protesters wanted to end." His voice rising in agitation, Kissinger exclaimed, "How plausible is such an interpretation of history?"

Out of the blue, he complained that people had no right to call him a "psychopath" for his conduct of the war. "It gets to be a nuisance," he said, "but I'm a big boy."

When the camera stopped rolling, Kissinger immediately said, "I bet McNamara was less strong than I was."

Kissinger seemed very pleased with himself. I must have looked disgusted.

"I love McNamara," he added. "He's a wonderful man."

Ah, the language of diplomacy.

As we packed up our gear, I asked Kissinger one last question. Something I really wanted to know. "What if the United States had allowed Vietnam to go communist after World War II?"

"Wouldn't have mattered very much," Kissinger muttered. Lights off. No camera recording what he was saying. "If the Vietnam domino had fallen then, no great loss."

With that he rose, stiffly, from his chair and left the room.

Fifty-eight thousand Americans died in the Vietnam War -- nearly 21,000 of them during Kissinger's watch. More than 600,000 Vietnamese soldiers were killed during the Nixon-Kissinger years. No one is certain how many civilians died.

And yet Kissinger had just told me that none of these deaths were necessary, from a geopolitical point of view.

He is an old man now and he shows no signs of remorse. And he has never displayed a willingness to challenge the foreign policy establishment that continues to consult and flatter him.

Kissinger promises a "full accounting" of the circumstances leading to the Sept. 11 tragedy and vows, "We will go where the facts lead us." But I don't know why anyone would believe him. Kissinger's specialty is the coverup. He knows where the bodies are buried, literally and figuratively, and he knows how to keep them there. And President George W. Bush knew all that when he appointed him.

Shares