Determined neutrality is a blissful condition -- and then you have to choose a side. This is the basic theme of Phillip Noyce's film adaptation of Graham Greene's "The Quiet American," but it's also true for Noyce himself.

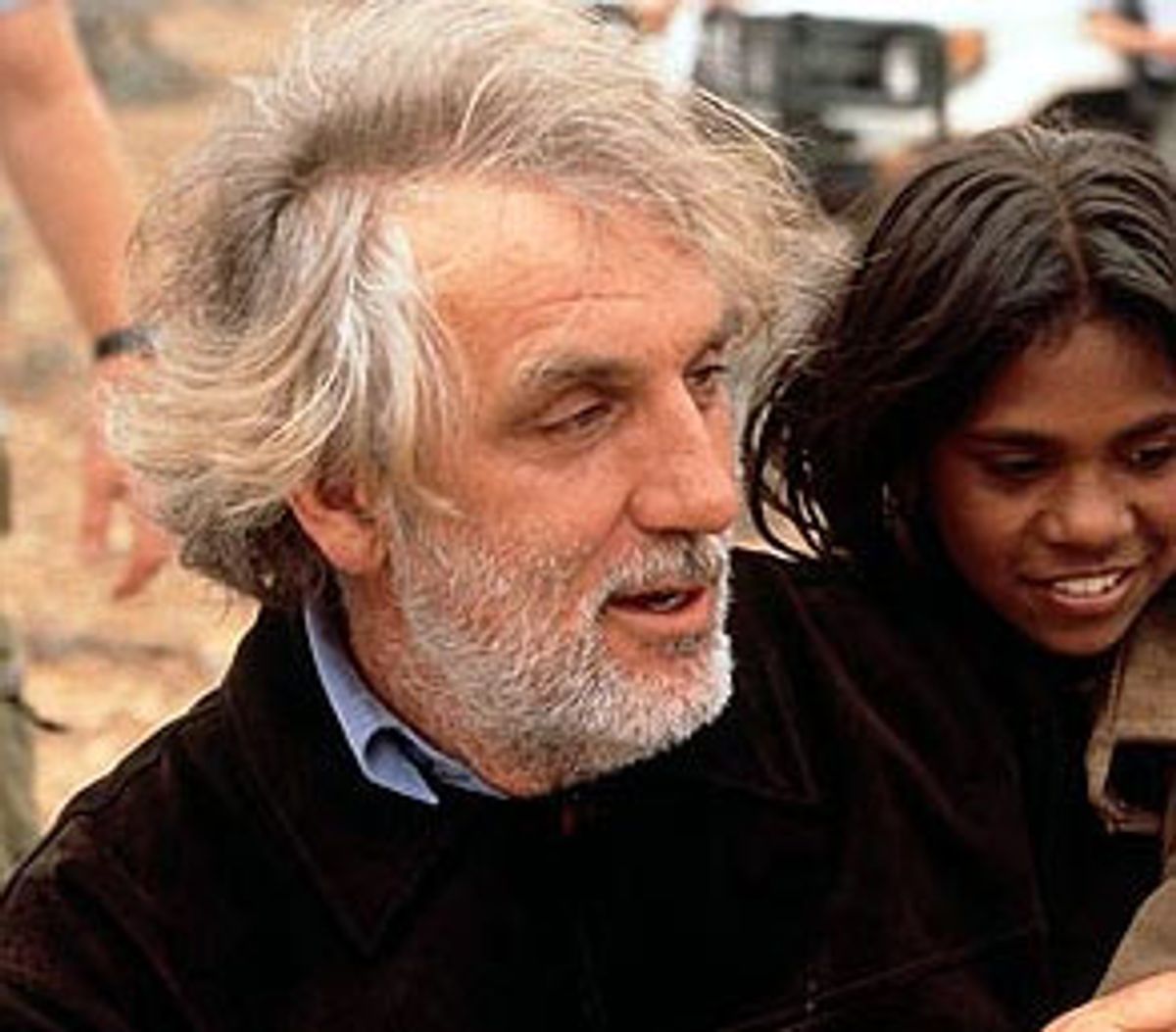

Noyce -- a Hollywood director by way of his native Australia -- has sustained, for the most part, a career filled with action-packed movies that fall squarely within the genre of political thriller: terrific, name-value actors, smart plots, real suspense, zero controversy. In the '90s he made the Tom Clancy adaptations "Patriot Games" and "Clear and Present Danger" as well as the stylish Down Under hit "Dead Calm." But Noyce's latest two movies deliver a blow against white, paternalistic, big-daddy government, just in time for an imminent war. The first -- and less likely to incite debate -- is "Rabbit-Proof Fence," a spare, heartfelt tale about an Aborigine girl and her conflict with a government that wants to separate her from her mother in an attempt to "breed out" her black blood. The other is "The Quiet American."

Graham Greene set his prescient novel in Saigon in 1952, three years before he finished it. In both novel and movie, British journalist Thomas Fowler (Michael Caine in his usual droll form) is doing his best to balance the various elements of his easy expat's existence: doing lots of opium, avoiding political views, evading work and living with his much younger mistress, Phuong, played with docile civility by the untrained Vietnamese actor Do Thi Hai Yen. When medical operative Alden Pyle (Brendan Fraser, in a very good performance) arrives in Saigon, Fowler finds himself competing to hold on to Phuong. This, combined with the gathering storm in Indochina, suddenly makes it impossible for Fowler to remain neutral.

After being shown to East Coast test audiences, the Miramax movie, which features a bombing sequence that post-9/11 audiences found disturbing, came close to being shelved stateside. Finally, Caine convinced Harvey Weinstein to bring it to the Toronto International Film Festival last year, to much critical acclaim.

I spoke with Noyce in the restaurant at the Regency Hotel in New York. Readers who haven't seen the film may want to see it before reading this plot-revealing interview.

America is all about patriotism these days, so let's start with that. Your movie features an American government operative sponsoring terrorism abroad. Is the movie anti-American?

I will quote Michael Caine as saying that it's "anti-a few Americans," the same ones that a majority of Americans would be "anti." I don't think that it's any secret that American foreign policy has a practice of using terrorist activities, sponsoring alternative political parties, candidates, movements, [effecting] the destabilization of governments, whether they're legitimately elected or not. And in many cases the exposure of those activities has been considered a responsibility. So no, I don't think it's anti-American, although at the time the book was written, Greene was accused of being anti-American, really for two reasons: one, Alden Pyle is a bit of a dunderhead. He's just a complete big bumbling idiot who's really not aware of any of the implications of what he's doing. I don't think that would have been true of a CIA operative at that time. And secondly, we have to remember the context that the book was written in, when Stalinism was still a valid and onerous enemy of America and of freedom everywhere. And a treatise like this might have been considered even by reasonable people to have been anti-American within the context of 1955.

The film is being released at a time when America is on the brink of what seems like an inevitable war.

The film was felt by some previous audiences, who saw it in rough cut at the end of 2001, to be anti-American and to be offensive. Of course, that was in the New York and New Jersey area in the wake of the violation of 9/11, when the images of carnage resulting from the aftermath of the terrorist bombing were not something that people wanted to see. It was not a time for self-criticism. And so the movie appeared at the wrong moment. I think people now are in a different era; the wounds have partially healed, and we're preparing for war. The basic message that Greene wrote about was just simply, look before you leap, a theme which has suddenly become extremely valid as the nation prepares for what may be another massive misadventure that could have just as catastrophic results as the one that Greene was writing about.

So in that sense do you think you and this film have -- however inadvertently -- become part of Hollywood's antiwar rallying cry?

Oh, I don't think so.

Sean Penn was on "Larry King" ...

Well, and good luck to him [chuckles]. I don't see many Democrats contributing to the debate, so why not a Hollywood actor, in the absence of much else? He's the best we've got! No, I don't think it will become part of Hollywood's antiwar movement. It's not antiwar; it's antiwar [as] declared by people who don't do their homework.

You've said that this book answers questions. Do you mean historical ones, or relevant current ones?

Well, no, the big question with the war against Vietnam is simply: Why? Not, What happened in the Gulf of Tonkin? Not, What happened in the Catholic archdiocese here in New York? Not, What decree was issued on which day? But what, in the American personality, compelled America to prosecute that war so vehemently for so long? I'm not talking about the day-to-day events, I'm talking about something within the makeup of the American political personality at that time, which, as you know, was influenced by a number of factors -- the defeat of Nazism, the rise of communism as the new "ism" and a very genuine enemy of freedom, the events of Dec. 7, 1941, the attack on America and abandonment of isolationism as a policy, the death of Roosevelt, who had promised the decolonization of Asia and Africa, and his replacement by Truman, ostensibly to bolster the democracies of Western Europe against communism, and therefore allow them to retain their money -- rich colonies.

All of these factors -- the war in Korea, and the near-defeat of the Allied forces against communism, Ho Chi Minh's choice of communism as a sponsor of his independence movement. So many factors that they all produced a certain outlook amid Americans at the time, that they believed they were fighting a holy war on behalf of freedom and humanity. As the melting pot of humanity, America felt justified, interestingly enough, in acting on behalf of the rest of us in the world, and that evangelical/political animal that emerged in the early 1950s, fighting the good fight, has endured to this day in many ways.

What was the question? I forget. [Laughter] Greene defines, through the caricature that he wrote of Alden Pyle, he defines some aspects of American foreign policy that resulted from all of those factors coalescing. And, in doing so, he answered a lot of questions about the war against the Vietnamese that hadn't yet been asked. And in many ways, Alden Pyle is alive and well today. And that's either a mark of Greene's brilliance, or the fact that some things just never change. I think his thesis has become very important to us, given the current administration. In theory, you've got a White House full of Alden Pyles. [Laughter] And that's scary.

Let's draw that analogy out a little further.

Well, George Bush is the ultimate Alden Pyle! He's hardly been out of the country, he's steeped in good intentions, believes he has the answer, is very naive, ultimately not that bright, and extremely dangerous. One only hopes that his advisors like Colin Powell are listened to carefully.

So how did a filmmaker like you become a political historian?

These last two films just came from experience. I didn't study modern history at high school or in university. I studied ancient history; I actually took Latin!

I bet that comes in handy.

Yes, sometimes "O me miserum" comes in handy: "Woe is me." But in the case of this movie, like so many Americans at the time, we in Australia went through the same journey from enthusiasm to complete and utter disillusionment. Except maybe we went through it more vividly than Americans did because we were the big domino at the end of the dominos that were due to fall. Remember, the domino theory was that unless a stand is taken against communism somewhere in Southeast Asia, inevitably this virus would spread from democracy to democracy and each would fall and the bottom of the dominoes was Australia. Huge island continent, which at the time had 13 or 14 million people, absolutely undefendable, except with the assistance of Uncle Sam. So we became involved in Vietnam as a means of spilling blood in order to impress America with our enthusiasm for its policies in the hope that -- as in the Second World War -- America would come to our aid, would defend us.

Would the phrase "human sacrifices" be apt? Australia ended up sending hundreds of thousands of people over there.

Yes, we did. That's correct. We committed the same number compared to our population as America did, and we had the same number of casualties, as a percentage of our commitment. We went though the draft, we waited every three months as a lotto wheel was spun and a celebrity pulled out a marble with a birthday on it, and if your birthday came out, you ended up in the jungles of South Vietnam. It was like a reverse lottery. If you win, you're in trouble. So I had two brothers, and next door was a family of two brothers. They went, and none of us were called out. Both came back, you know, and spread the disillusionment as they told us the truth of what was going on, the ridiculousness of it all. And I was taught, as a 14-year-old, to kill Vietnamese, during compulsory military training in Australia, in my high school, and to avoid a Vietnamese bamboo booby trap, and in a sense, as a 14-year-old in 1964, it was right to "go all the way with LBJ," which was a motto that our prime minister coined.

Prime Minister Holt.

Yes, who later drowned. So my interest in Vietnam came from having lived during that era, but also the interest in the CIA operative came from the fact that my father was in the Australian equivalent of the OSS. He was a spy. He was in the Zed force doing exactly the same thing, training operatives to go behind enemy lines. He didn't go, he just trained them on an island off the east coast of Australia. This was in 1945. And he told me the story of one guy called Minh who said to him, "I don't care about the Japanese, I'm just here to learn how to defeat the French." And at the time, there was no such place as Vietnam, there was just Indochina, and [my dad] realized of course that he was training a Vietnamese operative.

So that sounds like it's where you got your interest in politics.

I'd certainly been steeped in World War II spy stories from an early age. And making "Clear and Present Danger" and "Patriot Games" was a way to explore that world initially. "The Quiet American" extended that.

It was a nice decision to shoot most of the film in Saigon. As a result, the movie is a mystery and a love story, but might also be a travelogue. It's gorgeously evocative.

I suppose I was lucky to have [my cinematographer] Chris Doyle. In many ways, he is Thomas Fowler. He ran away from Australia and reinvented himself in Asia. "Rabbit-Proof Fence" [which he shot for me] was the first film that he had shot in his own country. He's found himself, like Fowler, in Asia. He could not exist in Australia. He goes there for a day or two and is always on edge. While we were shooting "Rabbit-Proof Fence," he would fly back to Asia for the weekend. On Friday morning he'd go straight from the set to Seoul, to Taiwan, to Hong Kong, just because he needed Asia. He's spend Saturday and Sunday and then on Sunday night he'd leave Beijing [or wherever] and arrive in Sydney at 6:30 on Monday morning, and be on set at 7:30. Constantly. Like Fowler, he is addicted to Asia. It's his lifeline.

But also, the location shoot is greatly helped by the passion that the Vietnamese have for this novel, for this story, because as much as it helps us to understand why we did what we did, remember that we rained hell on them. It's of even greater importance because they're on the receiving end.

Who was responsible for the extras in the bombing of Saigon square, some of whom I understand were actually limbless mine victims, rubbed with fake blood and raw meat?

The one who found all the extras for that sequence was my second unit director, Dang Nhat Minh. His father [a doctor working for the north] was killed by a B52 bomb. Dang was given the task of portraying the agony of the aftermath of that bombing. So he cast all of the extras, prepared them, trained them, worked with them, made it seem realistic.

The scene is crucial to the film, particularly for an American audience, because there's a huge turn there. The audience needs to be upset by what they see, because a huge shift is going to be required in their allegiance. They have to identify with Fowler's decision to act as judge and jury and executioner on his rival, and so the details in the description of the agony are what was important, and Dang Nhat Minh gave us those fine details in ways that I could never do as an outsider. Just the mother with the father who's dying, and the mother who shields her child with her conical straw hat. The casting of those people was all up to him.

You spent a good number of years scouting out possibilities for this film. What would you have done had Miramax not cleared the film for release in the States?

Well, eventually, we would have won because it was positively received in its U.K. release. We don't know if Michael Caine will be nominated for an Oscar at this moment, or if he'll win. But if he is nominated, and he does win, neither event would have occurred if the film hadn't been released in time, and that would have been a pity. To defend Harvey [Weinstein] for a moment, he already had so many horses in the awards race, with "The Hours," with "Chicago," "Gangs of New York," "Frida," that he had too many contenders to cope with as it was. Secondly, he had a genuine concern about the competition the film would have to face coming out in the fall.

Shares