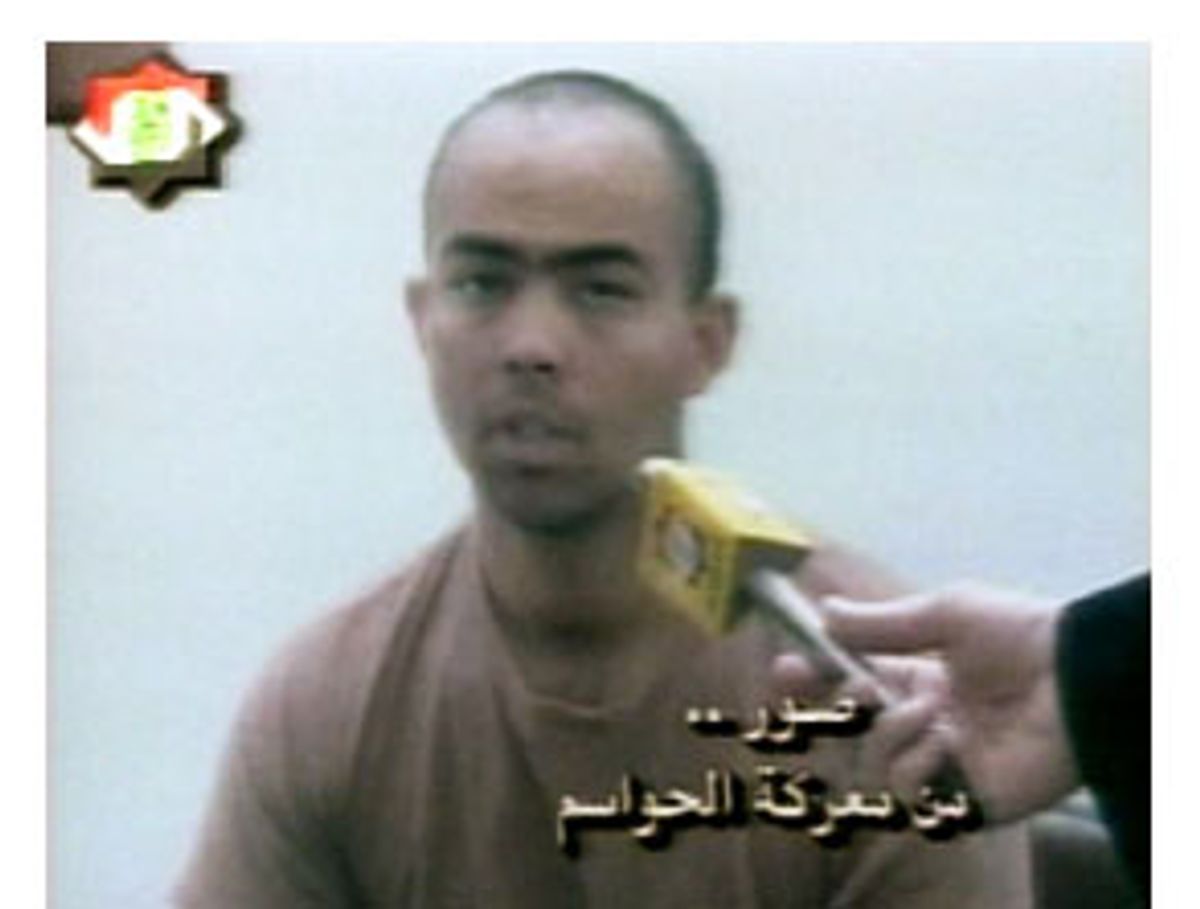

After days of watching the same images of the Baghdad skyline, a still life with the occasional eruptions of American missiles and thick billows of smoke, or of coalition troops rumbling through the desert, often in the grainy/greenish hues of "night vision," Sunday brought us something new, courtesy of Al-Jazeera. We were shown briefly, before Al-Jazeera decided to exercise discretion, American bodies in an Iraqi morgue and American captives paraded before the cameras. Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld was quick to accuse Iraq of violating the Geneva Conventions that forbid humiliating prisoners of war or subjecting them to what the conventions call "public curiosity," though it was unclear whether Iraq was in violation simply by inviting news media to videotape the troops (the media might have been committing an ethical breach, but that is another issue); in any case, American media have videotaped rows of Iraqi POWs, their hands cuffed behind them. Does that qualify as humiliation or public curiosity?

Assuming that the Iraqis hadn't executed any POWs -- and we really don't know whether they did -- one suspects that the real transgression here, in Rumsfeld's mind, is not against the POWs but against the rigid control of images by the administration. What Al-Jazeera provided was unauthorized. It was a peek behind the backdrop to the stage the administration had carefully constructed. No more stand-ups in Kuwait City or reporter "embeds" telling us breathlessly either how the troops were moving or how ready they were for combat. This was the other side of war -- the ugly side, the real side.

When the administration concocted the idea of placing reporters with military units, it was overcoming nearly 30 years of antagonism to the media, dating back to Vietnam. The reporters then roamed freely, documenting the chaos, the brutality and ultimately the futility of that ill-fated mission, and the military blamed them when public opinion turned against the war. As a consequence, from Grenada through Afghanistan, the military kept the press at a distance for fear they would undermine not necessarily the military's efforts on the battlefield but its public relations campaign at home.

It was something of a surprise, then, when the administration decided to provide what seemed to be full access to the battlefield, permitting the public to see the war in combat boots. It wasn't that Bush and Company, perhaps the most tight-lipped administration in American history, had suddenly gotten the religion of openness. It was that they realized while our troops were fighting the Iraqis, our reporters would be fighting Al-Jazeera and other new cable outlets. This was to be a war of images -- a war in which what the public saw and subsequently thought would be every bit as important as what our soldiers did. It was a war the administration knew it had to win.

With this in mind, the idea of embedding journalists with troops was a masterstroke. The White House certainly knew that reporters would bond with their units and identify with them. In effect, the press would serve as P.R. flacks for the operation, especially since one of the stipulations in granting the media access was that every interview would be on the record. So much for any of the soldiers criticizing the prosecution of the war. This was coverage that was virtually certain to be uncritical and supportive, essentially cheerleading, which, with a few exceptions, like the piece by embeds in Monday's Wall Street Journal on Iraqis who are "furious about the continuing military assault against their country," is exactly how it has turned out in these first days of battle. But the administration wasn't just relying on proximity. It also felt confident enough to embed the press because it knew this current generation of reporters, unlike the skeptical Vietnam generation, was not likely to challenge the conventional wisdom. This bunch was reliably docile. It was one of this claque, after all, that actually asked President Bush at a recent press conference how his faith was sustaining him in these troubled times. These guys were patsies.

Just how compliant the administration expected the journalists to be is illustrated by what seemed to be their second duty after their primary one of boosting the war. They were to bear witness to the notorious weapons of mass destruction that were the alleged causus belli, since the rest of the world thought the American military command itself was about as trustworthy as Vic on "The Shield" procuring evidence of drug dealing. But it wasn't just a matter of seeing the weapons being displayed. To be honest, there probably isn't a single reporter out there who could tell a canister of chemicals from a can of beans. It was a matter of experiencing them if need be. In last week's New Yorker, Hampton Sides described how he went to Kuwait City for training, largely to learn how to protect himself from biological and chemical attacks, before taking his assignment with the Reconnaissance Battalion of the 1st Marine Division. It was while undergoing that training that Sides had an epiphany as to why the military was really permitting embedding. He realized that the reporters were to serve as the canaries in the coal mine. They would provide the proof of the WMD, even if they had to endanger or even give their lives to do it. Sides turned in his credentials, got on a plane and headed home to his wife and children.

Still, even if the reporters were docile, there was a general expectation that with journalists in the field, beaming back reports while events were occurring, this war would look like no other. The Gulf War was the video-game war because it was viewed largely through the pilots' bombsights as if the public were sitting at a video-game console. Then Gen. Norman Schwarzkopf would appear with his pointer to tell viewers what they were seeing. The Iraq war was to be the Webcam war because every reporter was equipped with a camera or videophone to transmit the action. We were told we would see things we had never seen before, that we would experience battle as we never had before. This time we would taste the sand.

In some respects, this has been true, though once again the administration seems to have anticipated the effect and orchestrated it. Most wars are reported in what movie critics call "mise-en-scène." You get a sense of the whole thing, generally because the military command provides press briefings, like Schwarzkopf's, that provide the larger picture of what's happening: troop movements, campaigns, strategies, victories and defeats. The job of the reporters in the field is to provide texture and fill in the gaps. This war is being reported as montage. You get a series of quick cuts from one area to another but because there is virtually no larger picture being provided -- Gen. Tommy Franks, the head of command, faced the press only once in the first week of battle -- all the public gets are disparate pieces, and even those pieces cannot be assembled in any meaningful way. Defense Secretary Rumsfeld admitted, "What we are seeing is not the war in Iraq. What we are seeing are slices of the war in Iraq."

To prove Rumsfeld's point, while CBS ran a snippet of the Al-Jazeera POW tape and other networks posted stills from it, the American media are not showing the images that have grabbed the attention of the Arab world: The corpses of Iraqi soldiers, the wounded civilians in the hospital, the general destruction.

With slices instead of the whole, the administration has provided action without context, lots of trees without any forest as one anchorman put it, which is exactly what the president wants. The White House knows that so long as viewers are focusing on the troops, there will be public support for the war, though the one thing the administration might not have bargained for is that when things go badly, a war in montage can look an awful lot like chaos.

No doubt the White House also knows that while the battlefield images have the look and feel of reality, of being taken right in the middle of the maelstrom, reality isn't what it used to be. Most Americans nowadays process it differently. So-called reality programming has made the public more receptive to documentary images, but it has also taken out most of the bite and converted those images into another style of entertainment. That may be why the embed coverage of the Iraq war, which should be terrifying, instead seems like just another reality show. (At a press briefing last Saturday, Victoria Clarke, assistant secretary of defense for public affairs, bristled when a reporter referred to the bombardment of Baghdad as a "show" and a brief argument ensued, but the reporters, mostly foreigners it seemed, were clearly on to something.) Anyone watching cable news very early Sunday morning could see a tank battle outside Umm Qasr in southern Iraq and the effect was not very different from watching an extended episode of "Cops." One felt surprisingly disengaged.

Writing in the New York Times on Sunday, Alessandra Stanley observed that "Television cameras' usual route to battle is the trail left by its victims," and she cited the familiar images of refugees, hospital wards and open graves from recent wars. Her point was that the embeds were providing "an entirely new prism" through which to view war. Perhaps so, but the images on Al-Jazeera were an awful reminder that bodies and POWs still matter and that this war is not just a spectacular limited-run reality show that will end inevitably with Saddam's demise. They also reminded us that while we are seeing more of war via those embedded reporters, we may actually wind up knowing less -- which is probably just how the administration intended it to be.

Shares