As soon as I was spotted with the Believer on a Brooklyn subway platform, I was promptly accosted by a dark-eyed woman in her 20s wondering where she could find the debut issue. It didn't take long for word to get out that the new literary/cultural magazine published by the McSweeney's collective in San Francisco had hit the bookstores.

Already, the power of the Believer is strong.

The magazine, as has been reported elsewhere, is the brainchild of novelist Heidi Julavits, author of "The Mineral Palace," and Vendela Vida, who wrote the female rites-of-passage investigation "Girls on the Verge," and is, not incidentally, Dave Eggers' fiancée.

Physically, it's a very attractive product that has Vida's future husband's fingerprints all over it. Small ink drawings of animal skulls break up page after page of carefully justified, three-column text. There's nary a sans serif typeface in sight, nor an ad. Footnotes are present, though not in such abundance that they represent a separate meta-commentary -- these footnotes are really just footnotes. The masthead is demurely located on the back cover. The headlines and subheds are written in a gnomic style ("'Badlands' and the 'Innocence' of American Innocence, Featuring Martin Sheen as Donald Rumsfeld and a Voice-over by Our Laconic Complicity") that's clever, even if it ends up being tedious.

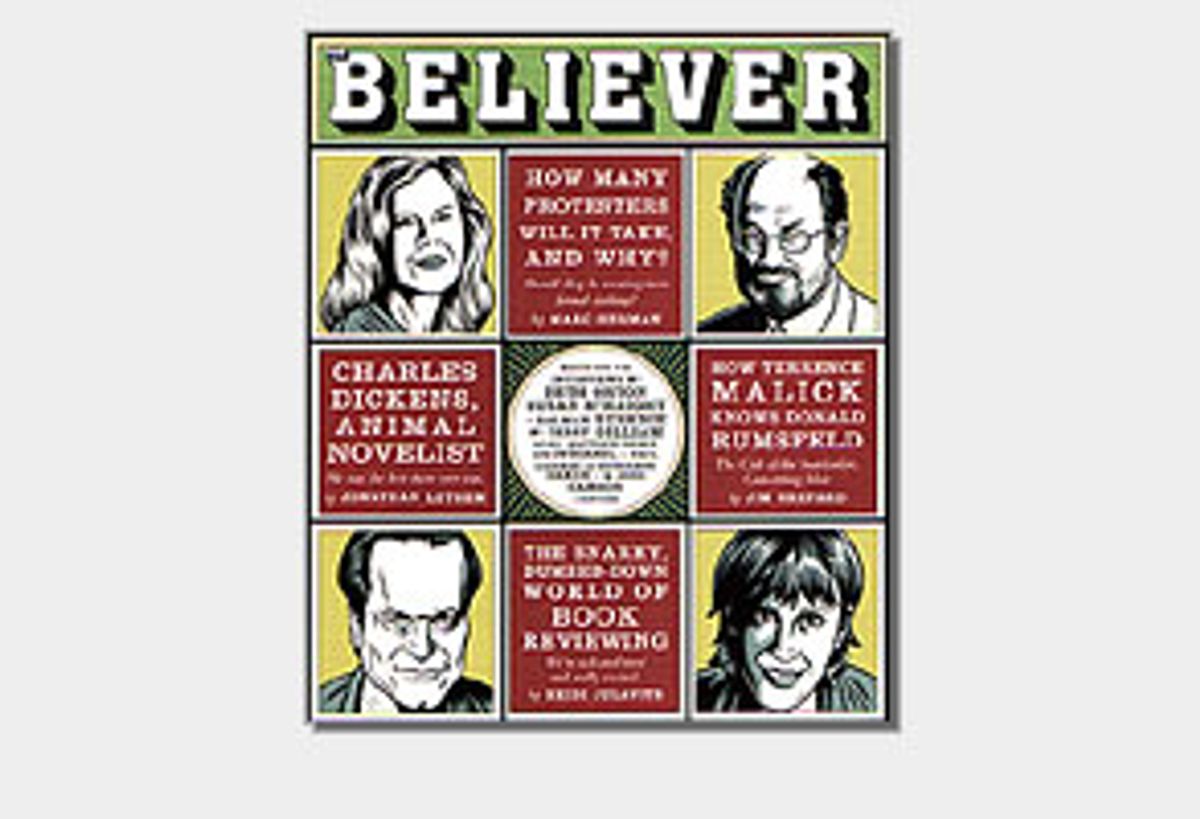

The longer pieces are paced by single-page literary experiments, including a travel-writing parody about a motel in Vermont, an analysis of the evolutionary development of the star-nosed mole, and an amusing attack on cute children. Cartoonist Charles Burns has contributed arresting, borderline-malevolent cover and interior art, including portraits of Salman Rushdie (who interviews Terry Gilliam) and Beth Orton, among others. There's an elaborate chart tracing the international provenance of magic realism. Overall, it's a compelling browse, even if it does suffer from the Eggers/McSweeney's fixation on some rather dried-out visual ideas borrowed from Joseph Cornell and the Museum of Jurassic Technology.

However, as an exercise in cultural journalism, at this stage, the Believer is pretty uneven. It gets your hopes up, but doesn't completely deliver on its quietly ambitious promise.

The magazine's avowed editorial mission is to stake out fresh territory, somewhere between Harper's or the Atlantic Monthly and a limited-circulation literary journal, but with an earnestness that the editors feel is lacking in these cynical times. "We will give people and books the benefit of the doubt," reads point No. 6 of the introductory 10-point "Notes about The Believer."

Now, it would be the easiest thing in the world to take some swipes at a publication whose editors have decided to run essentially unmolested Q & A interviews with an obscure English philosopher and Wes Anderson's favorite Indian character actor, and an intensely personal profile of the '80s-referencing band Interpol. The magazine's name, in fact, seems like deliberate bait, given the cultlike reverence that arises around anything Dave Eggers gets involved with. Eggers evidently advised the Believer's editors only on the design, while McSweeney's Publishing provided distribution services, but no funds. Still, it's hard to separate the Believer from Eggers' overall agenda, which is to restore some honesty and passion to American letters.

We'll see how it goes. My take on Eggers is that he's an interesting and occasionally inspired writer, but his unacknowledged significance is that he's one of the most important graphic designers of his generation. In fact, although his aesthetic is fairly reactionary and at times unbearably twee, he has a rare talent for the arcane art of typesetting and publication design.

The look of the Believer, with its sophisticated attempt to professionalize the shaggy, Bay Area broadsheets of the '60s and '70s, confirms my suspicion that Eggers' goal is not to become postmodernism's answer to Bennett Cerf, but to function as an update on the 18th century "gentleman printer" -- a contemporary Ben Franklin. (Eggers, however, wants to be Franklin minus the political and scientific enthusiasms, which distracted the founding father from the altogether more fascinating business of printing.)

The Believer's lead essay, however, is bound to convince some people that Eggers did more than recommend a typeface; some critics will doubtless conclude that he has locked Julavits and Vida in his mesmerist's gaze and commanded them to use the magazine to extend some of his own Peter Pan-ish cultural preoccupations. In "Rejoice! Believe! Be Strong and Read Hard!" Julavits, over the course of 9,000 words, complains about the state of contemporary book reviewing, mounting an argument against "snark," which she defines as a twisted ethic of cheap shots embodied in such smartass urban newspapers as New York Press and the New York Observer (full disclosure: I've written for both).

To summarize, she wants book reviews to be as lively as they are responsible; she never, ever wants to encounter an innocent reader who was turned off to a deserving author by the careerist flimflam of some hot-shot media Turk looking to score points.

This amounts to a manifesto -- one that Eggers himself would be sympathetic to. Unfortunately, it's almost always a bad idea to make the lead story in a new magazine a manifesto, especially when its verdicts are so flaccid (manifestoes are supposed to be fiery and emboldening). "I want to encourage readers to sample books they might otherwise never open or hear about," Julavits writes. Hoo-boy! Get out of my way as I rush the book-reviewing battlements, ready to poleax the purveyors of snark.

It's an even worse idea to lead with a manifesto when it buries your best article, in this case a very Harper's-esque report on San Francisco's protest culture by Marc Herman. The Believer's editors have forced it to languish behind Julavits' meanderings and the first seven pages of Paul LaFarge's insightful meditation on Nicholson Baker's debt to New England literary realism. (At least Herman's story fared better than the only other really good piece in the issue, co-articles editor Ed Park's disquisition on the vigorous career of "True Grit" author Charles Portis, which dwells meekly in the four-spot.)

Herman's take on the Bay Area's lazy legacy of antiwar protests is focused, intelligent, well-reported and downright frisky. His core point, presciently expressed well before the United States invaded Iraq, is that our current round of taking to the streets, unlike many prior forms of civil demonstration, is unlikely to achieve its goals. Why? Because Bay Area protest culture is just that: a culture. Its overriding interest is in perpetuating itself, not effecting change. Organizers are obsessed with being inclusive rather than introducing discipline to their troops. According to Herman's sources, this free-form tactic has made it easy for the media to ignore the protesters. Why give them column inches and airtime when all they do is deliver disorganized speeches, march on the wrong landmarks, and base their thinking more on Chomskian conspiracy theories than facts?

To me, Herman's story plus the Believer's distinctive, collectible design make it worth the $8 cover price. In future issues, I'd like to see a little more editorial ferocity. I think Julavits and Vida have it in them, but only time will tell. It might boil down to a fight between the good they want to do and the magazine they need readers to, well, believe in. The Believer hasn't made me one yet, but given the generally sorry state of the American magazine, I'm more than willing to be patient with my faith.

Shares