Saturday, after waking late in the afternoon, I spent the remaining daylight and early evening hours writing in this diary. Then I set out for the East Village, where I was assigned to meet a dirty-blond, tanned guy about my age who knew the parent doppelgängers portrayed in my audition video. I was late to meet him at the Wonder Bar on East 6th Street, and worried that that might have had something to do with the fact that he seemed somewhat less enthusiastic about being on a date with me than, say, fishing cigarette butts out of the East River with a tea strainer.

"How'd your date go?" a friend asked me when it was over.

"He talked about himself for 40 minutes," I reported.

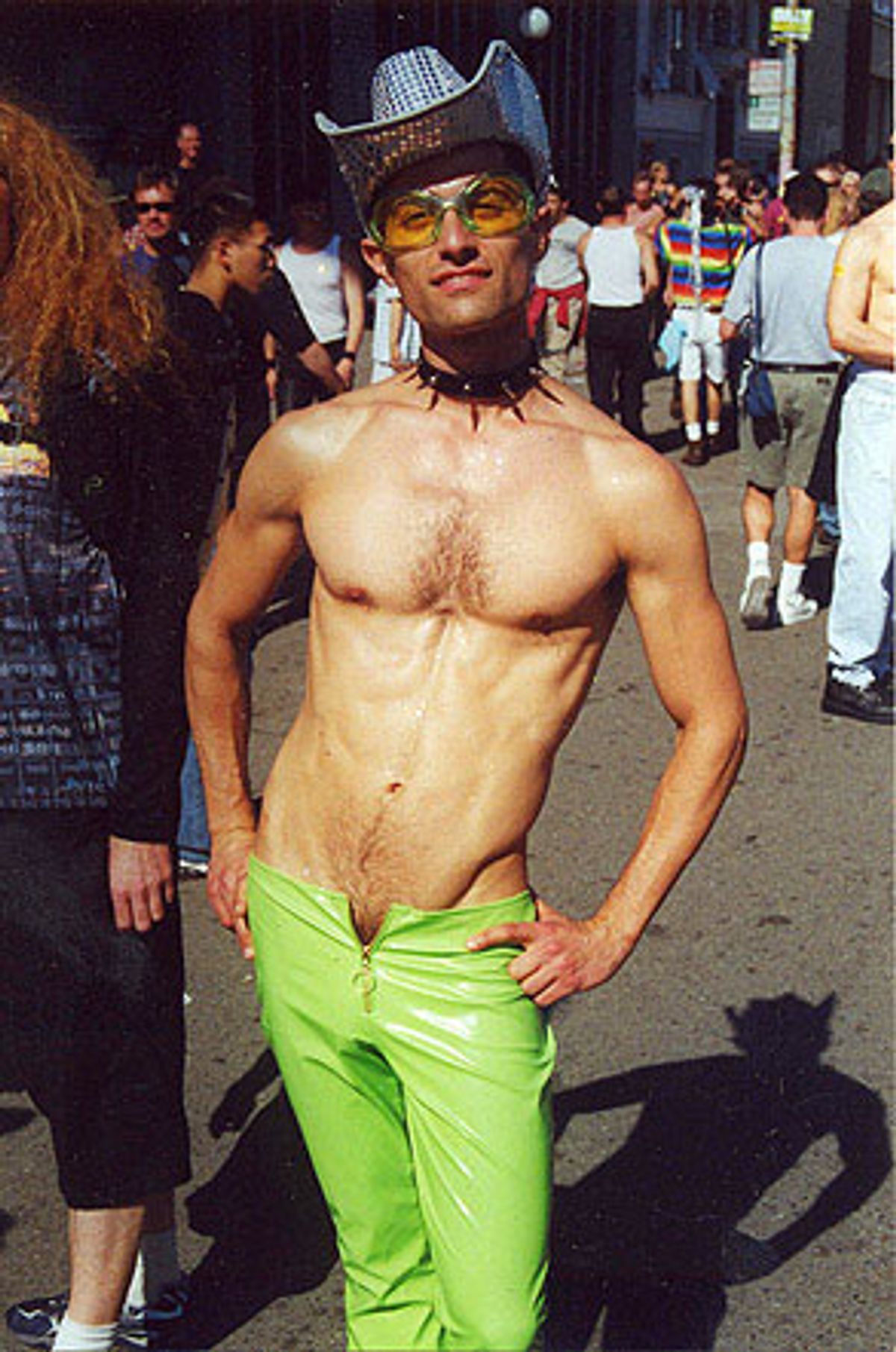

"Hot!" said the friend. It was now about 11 o'clock and the narrow bar had filled up with Sex Film candidates and other loose characters. Auditions continued Sunday but these were in essence closing ceremonies, the last official Sex Film activity for this group. For that reason, and because a number of us had seen the sun rise in unfamiliar neighborhoods that morning, the mood was several shades darker than it had been the night before; in addition to being hung over, we were starting to get paranoid. We were making calculations, weighing rumors, sizing up the competition, wondering darkly about that guy who used to be on "Third Rock From the Sun," counting up the number of auditions and dates we were called for, trying to divine our respective futures from everything John said and the way he said it and how it compared with what he had said to the others.

My friends among the candidates were confident of their failure. Keith hadn't been asked to audition again and was sure he'd been eliminated. Jarrad had another audition scheduled but no date. I, by contrast, felt pretty good about being two and two for dates and auditions -- Susan Shopmaker had called to invite me to appear again at noon the next day. Then, at the Wonder Bar, a guy told me he'd been called to audition all three days, had had two dates, and had been interviewed in private by HBO. Into this schedule I read my doom.

All night, hope and other illusions withered. No longer were we all one big happy family working in concert toward some bold and noble goal of artistic and sexual liberty. Now we were one big unhappy family, 34 dirty-minded siblings competing for the attention and love of a single parent who was endlessly affectionate but neglectful by virtue of his miraculous potency, charisma and consequent popularity. The dinner hour was upon us, and the competition for four or five servings of John's stew of art, achievement and notoriety was now too acute to ignore.

I'd underestimated the seriousness of this whole venture until now. I had fallen for John's ruse, had let him lull me into thinking this was sex therapy improv camp instead of an audition that would determine the course of the rest of my career and the rest of my life. He lulled us, sitting in that theater at the archives, into thinking that we were embarking on this daring adventure together, when of course most of us will be left behind. Now the drug of his presence and charisma was starting to wear off and the reality of the audition, of the rejection and disappointment that are inevitably in store for most of us, was starting to hurt. All I could remember from the week as I sidled through the crowded bar were the idiotic things I had said, the moment when his e-mail silence began, the sentences in this diary I now cringe to think that he read. The cycle is familiar because it is so much like love, or the realm of it in which we contemplate the possibility that we are no longer loved in return. We did not come to New York to date each other; we came to New York to date John. Now we wait by the phone. If we fell in love with him, the worse for us -- or the much, much better.

Having been shaken off by my date, I milled around making conversation with the other candidates. The flow of available small talk quickly grew infinitesimal before running completely dry. The awkwardness was keenest with the other gay guys, the most direct competition and, I increasingly thought, the most vulnerable. Throughout the week the project had produced a kind of gay superiority complex, in which we fags were chummy with John and with each other and enjoyed, if not flaunted, our majority status and our instinctual, gay-given comfort with the whole idea of fucking strangers on the one hand and fucking on film on the other.

The illusion that majority status benefited us was one of Saturday night's first casualties. In my conversation with John at his apartment, he had mentioned female ejaculation at least twice and said how he was becoming more and more interested in having the movie explore female sexuality. How many women, and straight men to fuck them, did the candidate pool offer for John to choose from? At best a handful. Now, at the Wonder Bar's closing ceremonies, I started envying heterosexual odds. Transgendered odds wouldn't be bad either. If the cast list didn't include the blond young hooker whose mid-video sex switch had mind-fucked even this gender-jaded group, I'd eat my chromosomes.

Milling around the Wonder Bar, all my gay male comrades could talk about was casting anxiety. I had a fairly long talk with "Plato," a guy I'd met one night about a year ago in the company of several other skinny white 20-something chem-friendly photographers, circus performers, hookers and drug dealers at the Los Angeles mansion of an art- and artist-collecting corporate lawyer. I'd been instantly attracted to Plato, not least because in addition to having those smoldering rent-boy good looks, he was a writer. At the Wonder Bar we commiserated for a while about the psychic brutalities of writing, and then about the building anxiety of the week's audition process.

Plato's anxiety, it turned out, was more severe than my own. One of the other candidates was his boyfriend, which offered two distinctly horrifying scenarios in which one would be cast and not the other. And then there was Plato's long-standing friendship with John, which already had had to weather the director's decision, after Plato had given what all agreed was the best audition in his life, to cast someone a little younger as Tommy Gnosis in the "Hedwig" movie. How would the friendship weather another disappointment at John's hands? How did that factor affect the rest of our chances? What must John be going through with his newly acquired status as star-maker, weighing friendships with people he'd disappointed before, matching sexual orientations and chemistries between close friends on the one hand and people he'd never met on the other, between people who live in this atmosphere and others like me who were giddy with the novelty of it?

I was preparing to leave the Wonder Bar when Jarrad arrived, resplendent in such magnificent Suppositori Spelling drag that no one recognized him. His powder-blue knee-high fuck-me pumps added at least six inches to his height, and the makeup and colorless Wonder Woman armored top and bikini underpants with no tuck completed the metamorphosis. I was relieved to see him, then dismayed as it became apparent that the bond we'd formed at Albert's bar the night before had succumbed to the oddsmaking calculation and anxiety that had poisoned the rest of the candidate pool. Why hadn't John assigned him a date? Jarrad fretted. I shrugged my shoulders. Our subsequent small talk could have fit comfortably into a dime bag.

At a loss for words, I looked around and saw the back of a head of spiky brown and white-pepper hair on a petite frame: John. I resolved to avoid him -- any interaction with the director in this crushing atmosphere could only result in misbehavior, feet-in-mouth and regret. A minute later the crowd had shifted so that he was right in front of me, the nape of his pale neck exposed and winking at me in the obscurity of the bar like a spinning aluminum lure in a murky pond. That skin seemed so naked, so inviting, so vulnerable, that my resolution to avoid John transformed into a considerably more powerful desire to kiss him, and before I could think through my actions, my lips were feeling the warmth of his neck and my tongue tasting the salt of his skin as I sucked lightly, came up for air, then kissed the spot once more.

John turned around, inquisitive but not necessarily surprised, then smiled broadly as he recognized me. He backed into me and drew my arm forward around him so that we were spooning standing up, then ground his bottom into my groin in time to the music, all the while maintaining his conversation with a woman I did not recognize. He bummed a puff of her cigarette and I squeezed him for a puff of my own. He didn't get it at first, then I said into his ear, Hook me up. Was that pushy? He held the cigarette to my mouth and I drew in smoke, exhaled and released him.

After parting with the blond, John turned to Jarrad and me. He admired Miss Spelling's outfit; we told him about our date at Albert's bar. Then the evening's signature conversational paralysis set in and the three of us stood there with absolutely nothing to say to one another.

"Well, I'm going to go circulate and talk to some of the others," John said. He left. Jarrad and I looked around anxiously. I reviewed what I'd said to John and found it insipid and self-aggrandizing. Then I dealt myself a few mental punches about kissing his neck. Why had I done it? I had no self-control, no cool. I'd swooped down on him like a bulimic before a buffet with a missing sneeze-guard. Whatever chance I'd had with this movie I'd just blown.

It was time to go. But as I was leaving the bar I once again got caught up in a conversation, this time with an uptown guy who cheered me up momentarily by saying he thought I had a really good shot at a lead. Why was that? I asked.

"Well you're probably the best-looking guy here," he said. "And your video was really great."

I didn't buy it about the looks, as much as I would have liked to -- there were hotter guys and besides that it seemed obvious that John hadn't summoned us all here for a more than usually sexually fraught beauty contest. And the movie? By Saturday night those videos seemed like they'd been made and screened three or four Miss America scandals ago. It no longer seemed to matter that my movie had been good, because the things that were good about it no longer seemed to matter. The movie had timing, music, humor, perversity of story, and of course the richness of the archive I had to play with (my mother bouncing her doll down the wide avenues of East Flatbush, the ruby spot of blood pooling on my newly shaved head). But those were not the qualities that John was looking for in his actors, not anymore. What mattered was acting, presence, charisma, and so far what had I offered him in my auditions? Cheap laughs.

I walked home in a dark mood and did my best to cultivate it. I had to start priming myself for an emotional performance the next day. The world was providing me with an abundance of material, starting with the blood bath our country was preparing to run in Iraq, stretching back to the bloodbath I had witnessed on Sept. 11 2001, the ruins of which lay three blocks from my current residence in TriBeCa and extending out into the infinitely bloody landscape of post-Oppenheimer anxiety.

The previous night I had dreamed that I was looking out on New York from my 28th-floor Juilliard dorm room in Lincoln Center, and a great seismic wave was rolling through the island toward us, pulverizing into fine radioactive dust block after block of glassy skyscrapers and stone apartment buildings bordering Central Park.

Walking home from the Wonder Bar I heard something rustling in a garbage can, freshly lined with a blue plastic bag. I stood before it a while, contemplating the hours of hunger and thirst it would take for that bag to become still. Then I did something I can only confess now that I am 3,000 miles from New York and New Yorkers, which is that I removed the liner and liberated a small rat, who went off into the dark recesses of the West Village to scavenge and breed.

Sunday I woke up with a new mantra: I am sad. I had recited it on my way home and as I lay sleepless in my bed, then as I woke the next morning an hour earlier than necessary, as I moped around the apartment and meditated on the image of people in business suits falling 80 stories in humiliating daylight. I felt vile about using those deaths as material; I used them some more. I listened eight or nine times to Olivier Messiaen's "Le Banquet Celeste," an organ work that straddles the gap between major and minor to wrenching emotional effect. I left the apartment with a churning emptiness in my gut and a noticeable tremor in my hands.

When I arrived at the casting office, I withdrew into a corner by staring into my laptop, tapping at it occasionally, and otherwise hiding within massive, DJ headphones. I wasn't trying to be subtle about the fact that I was writing about this whole process, and in the shaky state of sleep- and food-deprived, Messiaen-inspired, virtually ecstatic gloom, I for once was able to suppress my natural compulsion to simultaneously entertain and take care of everyone around me.

John called me in to audition with Plato. That was good news -- I wanted to go dark, and Plato was so dark he was practically opaque. John held me in the hallway while he sent Plato to the love seat.

"OK, the deal is that you're calling a sex line --" Fuck me. "And what you want this guy to do is reenact an ideal sexual scenario you always have in your mind, a sexual touchstone for you. And the scenario could be real or imagined."

Before he'd finished saying this into my ear I had my image. It was of the hermaphrodite in Fellini's "Satyricon," and I saw this beautiful young person (not, perhaps, as illegally young as Fellini portrayed him) lying naked, exposing his pale breasts and body and micropenis, hair transformed into a white froth in the refulgent summer sun on a wide slab of granite in the Yuba River where it flows through the Sierra foothills and where I spent three days one summer without leaving. I barely moved from that rock in those three days, and that's how I envisioned the scenario with the hermaphrodite, willfully stranded on this exalted aerie, 30 feet above a diving pool in the river, and canopied by an overhang that could also be described as a medium-size cave. Only a glimpse of this image came to me in that moment, accompanied by the beats of Messiaen's dissonances shimmering in the air like heat rising from the rock, but it told me down to the last detail everything I had to say and do for the next 20 minutes.

Oh, it started off veering toward farce just like the others -- I repeatedly had to ask Plato to make his deep voice higher, and I wound up talking dirty to him about his "little clit of a dick." This made the director laugh out loud, as Plato is famed across nine time zones for being distinctly not little, to the degree that the fact has even odds of becoming the subject of an Entertainment Weekly or maybe even Teen People headline were Plato to be cast. But from hormone and dick jokes Plato's gravity pulled me back down and at that lower altitude I was able to say a number of very involved things about the way loving him had made me feel whole because his manifest conflict between sexes reflected the kinds of less visible conflicts I have within my own identity, between ways of being, self-presentation, even my passionate (not necessarily sexual) orientations. We shared the experience of feeling "neither here nor there." I barely remember a line of the dialogue now, only this resonant memory of what it was like to feel that the words coming out of my mouth to describe my longing for this person who once loved me were having a palpable effect on the temperature and atmospheric pressure of the room.

Plato was right there with me, and I with him, me feigning this heartbreak and Plato pretending to be the sex worker pretending to be a hermaphrodite. (I don't, strictly speaking, know how much of a stretch that was for Plato.) The dialogue went on a long time. At Plato's perfectly timed cue it got dirty. Then it became sad and I began to suspect, without saying anything about it, that the reason I missed the hermaphrodite was that the hermaphrodite was dead. Plato said something to buck me up and I smiled painfully through the welling of tears in my eyes. When it was over there were a good 15 seconds of silence before John spoke in a husky voice, blinking back tears of his own. "That's what this movie has to be about," he said. "Because that person could be anybody."

I looked at John, as did Plato, and I didn't blink or change the haunted expression on my face. He said a few more things about the audition, ordered an improv hug between me and Plato, and then dismissed the two of us for the day.

Doubt hit me the moment I walked out of the room. Had it been good? Or merely melodramatic? Did that hand to the face come off as a hackneyed gesture or an organic expression of grief and exhaustion? Were John's tears an organic expression or an elaborately prepared consolation prize for a disappointment he already knew was in store for me? Had the dismissal from the day, and from the auditions for that matter, expressed, "I don't need to see any more of you because I have witnessed the orgasmic manifestation of God in your work," or something more along the lines of not needing to see any more of me, period?

I turned to Plato. We embraced for a long time. "That was really great," Plato said, beaming through his darkness. I felt a door open between him and me that had never been ajar in any of our limited encounters on either coast. And on a more selfish level, I felt hope.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

Monday, the day I left, it became clear not whether we were going to war (that had been transparent for some time) but when, and it was very soon. I had done this same flight on Sept. 15, 2001, and watched Port Authority and New York State police remove the two Arab passport-holding young men seated on either side of me, before they ransacked the interior of the airplane in search of box cutters and explosives. I had flown then so I could fly now, in part because there is no struggle with fear that a few dozen milligrams of a good Valium derivative can't take the edge off. (I didn't have the benefit of a prescription on that September 2001 flight.) The plane took off and landed in the usual way.

I was not home two days before I ran into a friend -- a documentary filmmaker and friend of John's for many years -- who welcomed me back and asked cheerfully how the audition went. Oh, and had I heard? The movie was cast. There were only four leads. One of them was Jarrad and the other was that guy from "Third Rock From the Sun." But the information was fifth-hand, he added, so I should take it with a grain of salt.

I wasn't sure how to take a hind kick to the gut by a wild stallion with a grain of salt, and I felt like nothing less was being asked of me. But if there's one thing three years at the Juilliard School train you to do, it is to smile and continue a conversation amicably after having had the wind knocked out of you by disappointment, and this is what I did with the documentary filmmaker. That night I lay in bed with a different kind of sleeplessness than what I'd experienced in New York. This agitated wakefulness exhausted not only me but my boyfriend, who had given me an ecstatic welcome home and now lay beside me awake as I tossed and turned. I found myself in the difficult position of begging solace from someone who not only was immensely relieved by the news that had hurt me, but whom I had spent that matchless week in New York hurting.

Still, I confided in him and he listened and did his best to comfort me. Some of his responses stung, though, as he held up a mirror before my feelings of rejection and envy. I confessed to him that as much as I wanted to be happy for Jarrad, all I could think was how difficult it would be to hear him talk about the monthlong improv workshop, about John this and John that, about the shooting schedule, the parties, the premiere.

"That's exactly how I would have felt if you'd been cast," my boyfriend said matter-of-factly.

Near dawn, I got out of bed and brought my computer to the hallway, where I e-mailed John. If my sources had it right, I wrote, I wouldn't be coming back east for the workshop, and so I wanted to thank him for inviting me to one of the strangest and most wonderful challenges -- certainly among those filed under "audition" -- of my life.

Then I slept. When I woke up a few hours later there was a reply in my in box: "Paul, I don't know who your sources are but I AM leaning towards different people right now -- partly because they are in relationships already (those things are a big deal as I discovered and you know). But absolutely nothing is for sure right now. I'm truly right in the middle of it all. Which is not to take away from how wonderful you were. Your improv about your intersex friend on the rock almost killed me it was so beautiful. Thank you so much and we'll talk. Love, JCM."

First I felt that kick in the gut again -- of course I was hoping he would refute the rumor entirely. Then I naturally enough took the intended solace in his praise, which on second glance brought me a new rush of pride. Your improv about your intersex friend on the rock. The director hadn't merely found it beautiful, he had bought it. With some stolen help from Fellini, from the transgendered blond Sex Film candidate, from Messiaen, even from John Updike (whose hooker in "Rabbit, Run" had a "brass froth" of pubic hair), with Plato's openness and spontaneity and immediacy, I had spontaneously written and performed a fiction and passed it off as memory. If only for a 20-minute audition, I'd surpassed my most grandiose fantasies about this venture. I did not leave New York a celebrity, pseudo or otherwise; I didn't even leave with a part. But for those minutes of sex and pathos on that battered love seat next to Plato, I was an actor.

As the days went by and the sting of rejection dulled, as the final cast list came out (with Plato and his boyfriend, with the transgendered hooker and the boy who fucked his bleeding girlfriend, with the guy who had three audition calls, two dates, and a private interview with HBO, with the Chinese woman who had played Korean in the "Hedwig" movie, with the guy who sent in an audition tape because he was "a complete whore," with a few more for good measure, but without Jarrad and without that guy from "Third Rock From the Sun"), I couldn't help thinking about another homosexual ingénue from the provinces who came to New York hoping to rise to stardom on the stage with the help of her 40-year-old idol.

Wasn't I a slightly less evil and less sick 21st century version of Eve Harrington? I'll grant that the antiheroine of "All about Eve" plotted her course with malice and subterfuge, and that she, unlike me, successfully completed it. But both of us had sat on couches located about 20 blocks from each other on Broadway and told our idol a startlingly sad story of love lost, had made that idol cry and made that idol believe our lies.

And though Eve fed off souls greater than her own for the sake of her career and artistry, while I merely held out my hand in earnestness and hope for that nourishment, both of us shared a dangerous instability. Both of us were searching for an identity we could not manifest on our own, but had to be conferred: by our respective mentors, by the stage, by fame. Both of us were or felt like frauds, and found that we were skilled in imitation because we were personal palimpsests onto which any character or effect could be easily overlaid.

In the second entry of this diary I wondered whether this audition would expose me, whether they would see my fraudulence, my incapacity to act truly under the imaginary circumstances of the play or in the reality of my own life. Or would they discover me, see me for who I really was and make me a star?

"Honey, there's a step in between, which is 'I accept myself as a real person,'" Albert replied. I did and do on some level. But there is something in me, the part of me hung up on celebrity and John's praise, the part of me crushed by his rejection, that does not accept the reality of who I am.

The theatrical fable of Eve's encounter with the great Margo Channing is told as a lesbian vampire story, the younger actress sucking the creative and erotic life out of her mentor. The passionate feelings I felt for John were real -- but they were also inextricable from the work he did and the gifts he could have chosen to bestow on me. As a lifelong collector of mentors, of substitute parents whether movie directors or Baroque music pedagogues or swinging bisexual couples, all of whom I feel compelled to write about in public and in intimate detail, I both hate this conflict of motive and passion and accept it as the inevitable consequence of being called. As for the pleasures and hazards of being chosen -- those are once more deferred.

Shares