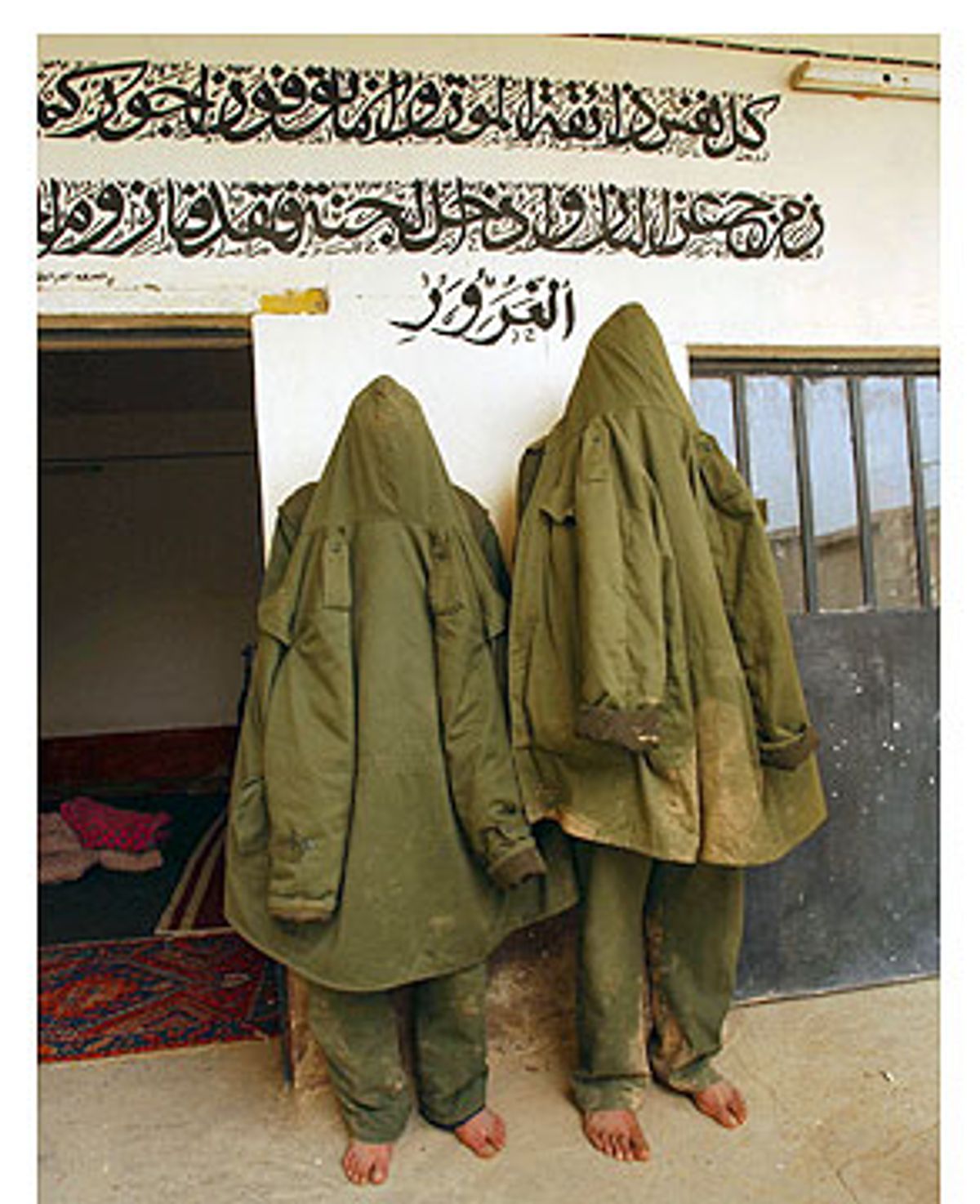

The two Iraqi Special Republican Guard members had either read too many spy novels or their lives were in real danger. They had requested that the meeting take place on neutral ground, in the central Baghdad office of a mutual acquaintance who also vouched for their authenticity. The two fighters from Saddam Hussein's elite unit, a staff sergeant and a private, covered their faces with scarves and towels and kept the interview short because they said they can't stay in one place for too long. Maybe they hoped the high drama would make up for the meager value of the information they were willing to provide.

The whole issue of Iraqi soldiers -- how many died or were wounded, how many deserted or fought to the end, where they are now -- is surrounded by a veil of secrecy. Neither the U.S. forces in Iraq nor the Iraqis themselves seem to be willing to delve into it too deep. As a result, conspiracy theories about Iraq's defeat, involving either treason or the U.S. use of "low-level nuclear devices," abound. Paranoia rules; even ordinary or wounded Iraqi soldiers, fearing that U.S. troops will arrest them, refuse to identify themselves. Members of the elite units have a better-founded fear of becoming the target of popular revenge, even for individual misdeeds. Says one former Republican Guard conscript: "Even today, after two years, if I find my officer in the street I'll beat him to a pulp."

The picture that emerges from the talk with the two Special Republican Guards is not flattering to the Iraqi armed forces. The least that can be said is that confusion reigned. The U.S. military's claims during the war that it had destroyed the enemy leadership's ability to command and control its troops seem accurate. The staff sergeant, who served under an officer who commanded a unit of 60 soldiers, says he had no idea of the position of any of the other units in the area in south Baghdad that he was assigned to defend. He had no idea of the troop strength in his immediate vicinity, nor any clear idea of the line of command. What's more, he says that food stocks ran low several weeks before the fall of Baghdad and he ran out of ammunition during the final battle. Similar stories are repeated in other parts of the army as well.

The American firepower was overwhelming. In the suburbs and on the outskirts of Baghdad hundreds of burned-out Iraqi tanks and armored personnel carriers can be seen by the side of the road, apparent victims of direct hits from the air. Helmets, shoes and, here and there, uniform jackets are scattered around many abandoned positions.

No wonder most Iraqi soldiers just put down their arms and went home. "When I ran out of bullets, I took off my uniform, put on civilian clothes, and walked home," says the sergeant. He constantly contradicts himself and his comrade during the interview, and much of what they say must be seen in the light of what they claim was their continuing commitment to the old regime, their willingness to take up arms again, and in the case of the sergeant, even to carry out "suicide operations."

"We get instructions from President Saddam Hussein," says the sergeant. "We know where he is, and he sends us leaflets with his wishes." Later, when asked why the leadership and the president did not put up more of a fight, he changes his story. "The president disappeared. God knows, maybe he died in the bombardments." Regardless of the fate of Saddam Hussein, the two soldiers say they will fight the Americans in the future. "We don't need leadership, we do not need officers, we know what to do."

The unit was devastated by the American bombardments, they both say, with cluster bombs doing most of the damage. Universally, Iraqi troops say the cluster bombs -- which throw bomblets over a wide distance and were widely used by the U.S. on Iraqi troops in the open -- did terrible damage. (The use of cluster bombs is controversial because of their relatively high failure rate, which results in postwar accidents involving unexploded munitions. Both the U.S. and British commands have denied that they dropped cluster bombs in areas where civilians were present.) The sergeant says that of the 60 soldiers in his unit, only 15 survived. This claim contradicts his earlier statement that many soldiers deserted even before the fighting broke out. He estimates that most other units in his vicinity suffered comparable losses.

According to U.S. Central Command, more than 7,000 Iraqi fighters -- both regular and irregular troops -- were taken prisoner; the number of deserters is estimated to be about the same. The U.S. military calculates that 2,000 to 3,000 Iraqi fighters were killed during the first U.S. foray into Baghdad alone, but it has issued no estimate of the total casualties, military or civilian. (Since the Vietnam War, the Pentagon, wary of bad publicity, has not kept lists of enemy casualties.) Before it fell, the Iraqi government claimed that more than 1,200 civilians had been killed. Human rights groups have come up with equal or slightly higher figures, but all estimates are unreliable at this point.

Certainly Iraqi military casualties must have been tremendous. The Iraqi military was thought to number 300,000 to 400,000 troops, with the strength of the Republican Guard estimated at 80,000. Several days before the fall of Baghdad, U.S. Central Command believed that two of the Republican Guard's six divisions -- exposed in their front-line positions to the inconceivable firepower of the U.S. Air Force -- had been smashed to the point where they no longer constituted an effective fighting unit. (Assuming a division comprises 13,000 men, that means a significant percentage of 26,000 troops had been killed or wounded.) During the fighting in and around Baghdad the International Committee of the Red Cross reported that one front-line hospital, Yarmouk, was confronted with an incredible influx of 100 wounded people, mostly military, per hour. There are also reports that some 600 people were buried there in the grounds. One doctor at the Yarmouk hospital confirms that but says they were all dug up and transferred to cemeteries.

At the main Rashid military hospital on the outskirts of Baghdad, some 60 identified bodies of soldiers remained buried in the hospital grounds over the weekend, out of at least 200. (A list of the dead posted outside the hospital had 200 names on it, but it was not clear how many of the dead had yet to be identified.) The hospital gate swings open periodically to let out taxis with coffins tied to the roof: families that have just collected their relatives and are taking them to the cemetery for reburial. Identification teams are still at work on the site, but it is impossible to find out how many soldiers were buried there in total. American troops are guarding the gates and have specific orders not to let the press into the grounds. One Iraqi volunteer at the gate says: "It smells very bad there, it is terrible, and it is not good for your health." The U.S. soldiers at the gate explain that according to their orders, the press is banned to protect the privacy of the families who go there to collect their loved ones.

At the nearby Zawariyeh hospital, Ahmed Jabbar has just learned where the body of his 22-year-old brother Mohammed, an army conscript, is. A team at the hospital is computerizing all the information about fallen soldiers. "He is at the Rashid hospital. Come with us to collect him," Ahmed asks, unaware of the U.S. ban on the press.

His uncle, Nazal Dkhel, is the head of the extended family and accompanies Ahmed on his grim quest. "Mohammed did not complain about the army service," says Dkhel, who looks grief-stricken and dignified. "He did his compulsory service and there was really nothing anybody could do about that. It was his duty."

Ahmed says that the last time they saw Mohammed, some three weeks before, his brother had not been worried. But when they didn't hear from him even after the war, they came to Baghdad from the nearby town of Faluja to search for him. From the available information they learned that Mohammed was hit by U.S. bombs on one of the last days of the war.

They are not angry with the U.S. "This happened and it is now in the past," says Dkhel. "We now have to live with the new situation."

The family jumps into a waiting taxi carrying an empty coffin and heads to the Rashid hospital.

Apart from the many dead buried in the grounds, some 300 wounded soldiers were also present at the Rashid at the end of the war. Now they have been distributed to other hospitals, notably two in the poor and populous Shia neighborhood Al Thawra, formerly known as Saddam City.

The Jaddariyeh Hospital in Thawra is being guarded not by Americans but by dozens of jumpy young men with Kalashnikov assault rifles, under the direction of a bearded and turban-wearing sayid (Shia sheik). The U.S. troops do not maintain a presence in Thawra, and from the hostile way they asked if I was from the U.S., it seems that Americans are not welcome.

Inside the hospital, the doctors insist that all the wounded soldiers have gone home. "They were wounded more than a week ago," says one. "We treated them and sent them away." The hospital does provide long-term care, though, to civilian patients who have been there for several weeks. The questions about soldiers anger the hospital staff. "Why ask about soldiers?" asks one. "The war made many more civilian casualties. This was an act of American barbarism against the people of Iraq." As we leave, a member of the staff shouts after us: "If you came to spy, why didn't you just wear your American uniform?"

Among the civilian casualties in the hospital was one boy who had just been brought in after having supposedly picked up a cluster bomb: wounds covered his face. Another man was lying in the ward with a serious abdominal wound; he had been at the hospital for 19 days already.

Mistrust and paranoia are ever present, and there is reason to suspect that political groups with an anti-American agenda are helping foment them. Many of the slogans of the regularly returning protesters in the city center -- demanding an end to the U.S. occupation, calling for the restoration of security and services, and decrying "American barbarism" -- as well as many of the expressions used by people who have known connections to Saddam's Baath party, are too similar to be a coincidence.

The Republican Guard sergeant brags that the "old networks" are still functional. He warns that he will go after "traitors" who helped the Americans capture Baghdad, officers who told their men not to fight and who held up supplies and even led the Americans to Iraqi positions.

Wamid Nathmi, a political scientist who used to be regarded as something as close to an opposition figure as one could get in Iraq, has made a 180-degree turn and now subscribes to paranoid theories about how Baghdad could have fallen. At first, he says, he blamed "traitors," but now he hints that Americans used some new and terrible weapon, "maybe a limited-scale nuclear device," against the soldiers defending the International Airport. "Go to the airport," he urges. "The Americans keep it closed to everybody, and I have heard there are hundreds or thousands of dead Iraqi soldiers there who have been burned all over, not shot. That is how they were able to defeat us."

Shares