From a treatise on Bruce's butt to an essay on Prince's half-naked ass, more than 100 scholarly presentations at a recent Seattle conference uncovered the deeper meanings of pop music. Titles like "Supa Dupa Fly," "White Noise Supremacists," and "Oh Bondage, Up Yours!" lured some 500 academics and journalists to the second annual Pop Conference at Experience Music Project, the institution funded by Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen, from April 10 to 13. Jampacked with the politics of bebop and deconstructionist analysis of hip-hop, the conference might sound ponderous to outsiders. But then, rock 'n' roll has never been about following the rules or being predictable.

Actually, the full name of the presentation on Springsteen's behind was "Bruce's Butt: Masculinity, Patriotism and Rock's Ecstatic Body." In an era of acronyms, from "btw" to J.Lo, it's somewhat daunting to burrow through "papers" with 17-word titles, interrupted by semicolons -- and even more astonishing to find them illuminating, inspiring and fun.

In a frenzy at the overhead projector, Tony Mitchell of the University of Technology in Sydney flailed photos of global hip-hop acts in a kind of poetry slam, as if proving that rap exists outside the U.S. Both the style and substance of his performance wowed the crowd of fellow professors, grad students, writers and musicians.

This meeting of writers and thinkers from around the pop-culture globe was meant to find common cause, according to Eric Weisbard, head of EMP's education department. Was it a culture clash? While some attendees wore both academic and journalistic hats, both parties came slinging lingo, peppering their papers with music-industry slang or critical terms like "conflation" and "commodification."

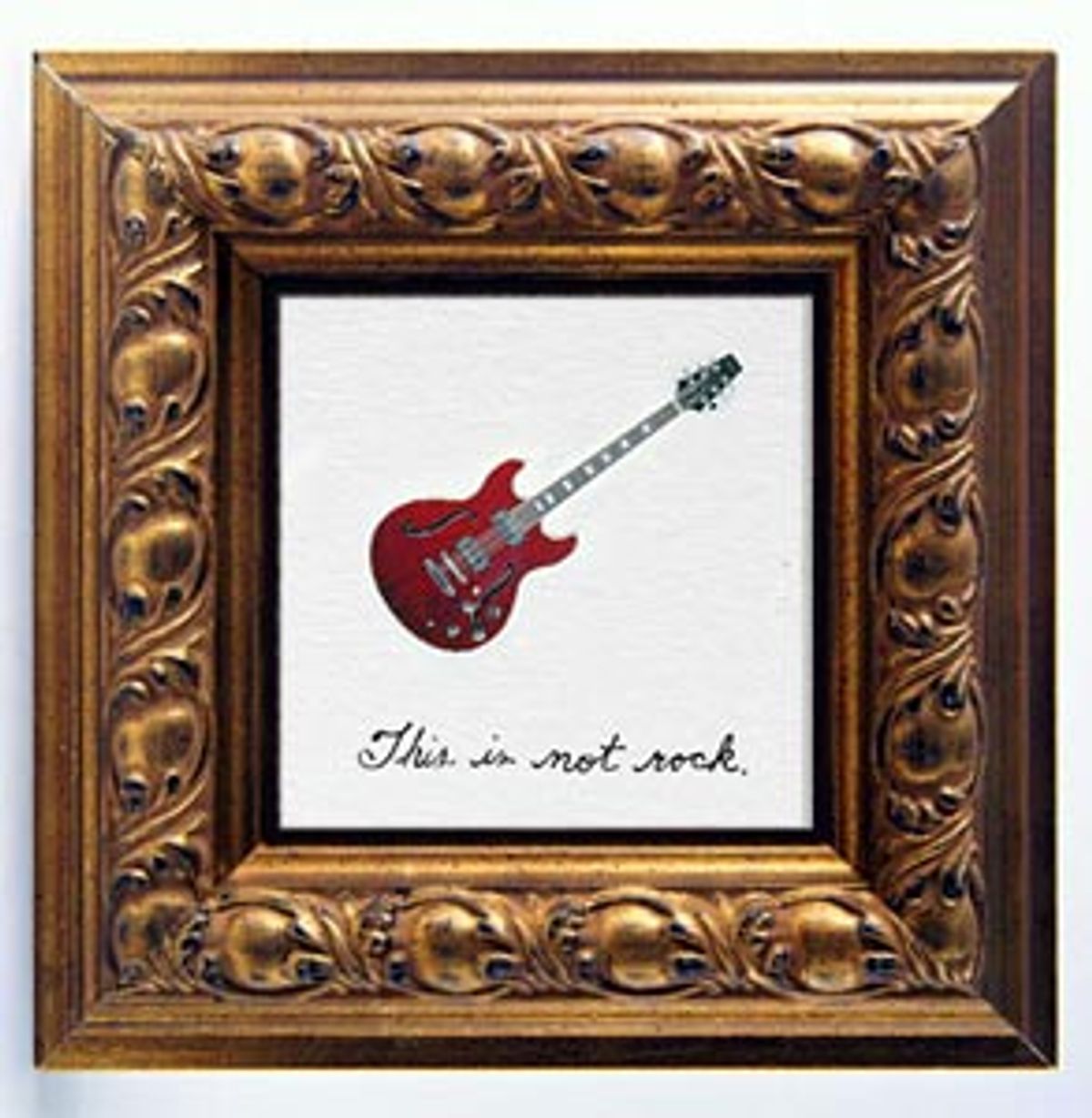

This brainiac approach may seem jarring. Highbrow analysis of pop music seems, at least at first, antithetical to rock's spirit of rebellion, wreckage and debauchery. This kind of examination seems suited to loftier subjects than punk, disco, techno and karaoke. When references to Iggy Pop share a podium with Bela Bartók, it's not about "lust for life." Or is it?

Through the corridors of this colorful blob of a museum built by leading postmodern architect Frank O. Gehry, past the gift shop with its Jimi Hendrix and Kurt Cobain posters, Beatles lunchboxes, T-shirts and paraphernalia, attendees crammed into the Learning Lab to hear University of London prof Marybeth Hamilton read an intriguing account on the unearthing of a rare collection of "race records."

"Who knew the Delta blues was discovered under the bed of a closeted gay alcoholic living in a Brooklyn YMCA?" exclaims the wide-eyed Weisbard, grabbing a bite of turkey on focaccia between panels. The former Spin and Village Voice editor who organized this hybrid seminar explains, "It's less formal than academic conferences and more risk-taking than industry conventions." It might also be the only music gathering with empty hallways once a session starts. Everyone seemed as content with ivory-tower pursuits as they would be at Tower Records; collectively, they've written more than 50 books on subjects from Muddy Waters to heavy metal.

Greil Marcus, the author of "Lipstick Traces," "Mystery Train," and "The Dustbin of History" (and a former Salon columnist), launched the shindig with a keynote speech that tenderly invoked a series of songs spanning time and genre -- from a 1929 version of "Man of Constant Sorrow" to the snappy rendition in the Coen brothers' "O Brother Where Art Thou?" The plaintive promise and power of the Rolling Stones' "Gimme Shelter" sucked the audience into his reverie.

Early the next morning, we heard Dionysian festivals compared to mosh pits, Pentecostal speaking in tongues connected to scat singers, and the tango linked to jazz. The so-called dean of rock critics, Robert Christgau, who's been grading record albums from A+ to F for his Village Voice column since the 1960s, likened the revelry of ancient Greeks to "Rock's Ecstatic Release."

The conference's airy theme, "Rewriting the Story of Popular Music," was a revisionist's wet dream. After all, it's still early days for the study of 20th century tunes. While "Chicken Boogie" sounds as lively today as when it was brand-new 60 years ago, even Grace Jones' hits are now more than 20 years old. Is this historical and sociological dissection a form of spindle-gazing contemplation to pump up the volume on "low" culture -- or a worthy inquiry? Rock music isn't rocket science, but the gobs of insightful material at the Pop Conference rendered what might seem to some a ridiculous pursuit into something sublime.

Synapses snapped when Ned Sublette of Qbadisc Records suggested that not all roads in pop-music history lead to rock 'n' roll. He proposed Cuban music as the elephant in pop's kitchen, arguing its central influence from the big band era to a string of rock hits ("Rock Around the Clock," "Daytripper," "Louie Louie"). Dazzling his audience with facts and sound effects, Sublette described a fertile musical crescent from New Orleans to Haiti, with Havana as its clearinghouse.

Heady stuff for 10:30 in the morning, but the receptive crowd was jazzed as they dashed to soak up more. Historians, sociologists and ethno-musicologists rubbed tweedy elbows with denim-sleeved writers. With more than 100 speakers spread throughout three simultaneous sessions, it was a scramble to catch every provocative idea or insightful theory.

The "Women in Question" panel was a lively rally at Rock and Roll Grad School. Lee Ann Fullington from the University of Liverpool related her survey on the male preserve of record shops. Gayle Wald raved about Rosetta Tharpe, a 1940s blues guitarist who "played like a man." Professor/musician Lisa Louise Rhodes reassessed rock's sexual double standard with moderator and Austin Chronicle writer Margaret Moser, who unfurled tales drawn from her years as a groupie.

"There's a different approach at strictly academic conferences, which can feel like a sentencing," said Rhodes. "More than one or two slight attempts at levity are viewed as undercutting the seriousness of your work. At EMP, everyone seemed to be having such a good time."

Both the profane and the profound filled this music nerd-fest. Speakers addressed the erasure of blackness in indie rock, the theft of blackness by white songbirds, and the preservation of whiteness in "Celtic Confederate" tunes. Yet the head trip rarely felt like a lecture. Barnard College professor Donna Gaines, an intimate of the Ramones, who wrote "Misfit's Manifesto: The Spiritual Journey of a Rock & Roll Heart," quoted sociologist Emile Durkheim as well as late guitar legend Johnny Thunders.

Whether participants were waxing rhapsodic on Jeff Buckley, going dissonant on the White Stripes or, like novelist and musician Darcey Steinke, offering a lyrical ode to Elvis, the proceedings often felt like George Sand lying under Chopin's piano for a visceral listening experience.

It wasn't all weighty. A rousing lunchtime concert by Jon Langford of the Mekons offered pithy three-chord songs and witty anecdotal commentary on his "Sorry Life in the Punk Rock Trenches."

The "Ego Trip" round table was another crowd pleaser, struggling to answer various hip-hop-related questions, including "Who's the next Tupac?" The collective of writers of color who self-published "Ego Trip's Book of Rap Lists" offered such zingers as "Wu-Tang Clan is the Kiss of rap," and led a singalong to Missy Elliot, advising the audience to replace "nigga" with "ninja."

Academics, of course, aren't hampered by such journalistic considerations as word count and deadline. "Writers have to know how to swing a sentence, how to make (occasionally) complex ideas seem simple and/or sexy," notes Pat Blashill, a freelancer for Wired and Rolling Stone who presented "Darth Vader Was a Black Man" (on the topic of techno "Afronauts"). "Academics, on the other hand, don't have to squeeze ideas into a small space next to photos of J.Lo in the shower."

Blashill says he welcomes the breadth of exploration and the opportunity to grapple with larger questions. "The conference forced writers to step up to the plate and deliver bona fide ideas, and forced assistant professors to drop the $20 words." To communicate and entertain. Arguably, if the conference's "Discoteria" panel had happened under the twirling lights of EMP's "A Decade of Saturday Nights" exhibit, next to Labelle costumes and Studio 54's moon and spoon, it might have packed more punch.

One of the final panels provided a delicious sendup of academic papers by addressing "sludge," those ubiquitous, crass formal devices found in every clichéd piano intro and guitar lick, across almost every pop genre. "The E String Scrape" featured examples from Bon Jovi, Michael Bolton and REO Speedwagon. "The Cowbell as Party-Down Signifier" cited a slew of examples, including Nazareth and Blue Oyster Cult -- each excerpt drawing louder and cheaper laughs.

British professor John Street, who presented "Pop Star as Politician," reflected on the big picture: "These conferences serve to, 1) make one feel inadequate, and 2) revive enthusiasm. This worked brilliantly on both counts."

Despite the overwhelming blur, those gathered were stoked and insatiable for discourse at the reception. "It's as much about building a new kind of community, as presenting ideas," says Weisbard. "Almost every person had a different experience, which is true to the spirit of popular music."

He's editing a volume of conference papers for Harvard University Press to publish next year. "People care when writing is good, when thoughts are new, when culture has some zing to it," Weisbard says. "All we can try to do is make something interesting and let the sparks fly."

Lisa Louise Rhodes admits that being a pop fan can make her feel like an outcast in the academic world. "But at EMP, among so many bright people who think pop music matters," she says, "it felt like coming home."

Shares