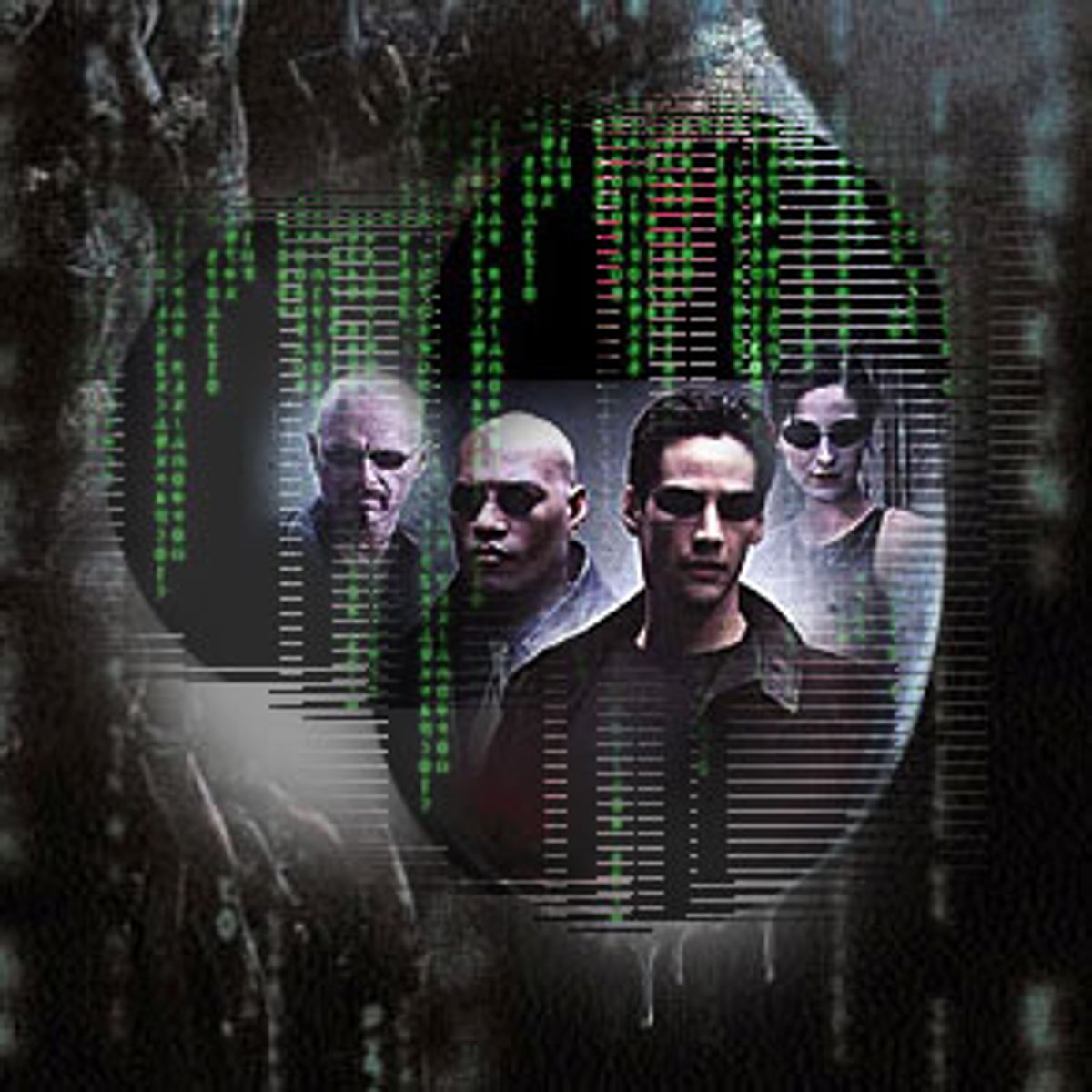

An information technology manager visits the graveyard shift of build operators, the nighttime nerds who monitor the company's Web site through the early morning hours. He glances over at a lone workstation, where the staff has a movie on constant play, on endless repeat, often with the sound turned down. That movie? "The Matrix."

The film -- and its upcoming two sequels, "Reloaded" and "Revolutions" -- are tech-geek nirvana. But four years have passed since the first "Matrix," and in that time, the tech world -- the tech economy, anyway -- has imploded. In 1999, every programmer in the audience could picture himself hacking his own brain; in 2003, we're happy to slog along on B-list inventory-control projects, if only to ensure a paycheck.

The future that "The Matrix" illuminated has endless appeal for the technically inclined. It is dystopic science fiction -- a favorite subgenre of books, movies and video games for techies. It promised that a PVC-clad, lesbian-chic hacker hottie, like Trinity, might approach them in a crowded bar sometime soon. And as a final incentive, it told them they'd be able to learn drunken boxing just by thinking about it really hard, rather than actually working out.

But the main appeal of the "matrix" is that it's programmed and therefore able to be hacked. With enough knowledge, we can bend our environment to our will! Four years ago, at the height of technology economy, when geeks ruled the earth, the idea held sway. But the real world proved to be much less manipulable than any "hacker proof" database.

None of this will diminish the appeal of the sequels to "The Matrix" -- but the experience of seeing "Reloaded" will be caught up in a new corporate reality.

In Seattle, those of a certain mindset will line up around 10 p.m. opening night for the midnight showing. We'll do so in front of Cinerama, a rehabilitated state-of-the-art digital theater bankrolled by Paul Allen and his Microsoft millions. In the years since the first "Matrix" was released, we've reenacted this ritual for "Star Wars: Episode I" (a mistake not repeated for Episode II), both "Harry Potter" movies and, of course, both "Lord of the Rings" movies.

In the line, among the geek elite, no one gets mocked for trotting out their Elrond cape or Slytherin scarf. We'll see a fair number of black trench coats on "Reloaded's" opening night.

But the Cinerama isn't just a geek staple anymore -- it's become the venue for tech companies in Seattle. The line is littered with people wearing corporate swag, their fleece vests embroidered with company logos.

Tech company executives (the few that have survived the past few years) send their executive assistants -- almost always female, blonde, and accompanied by their smoking buddies -- to pick up 200 tickets for the team. They buy up all the shows and hand out tickets as if to compensate for the lack of cost-of-living raises for the past three years.

The managers, too, think they're Neo -- or at least that they're part of the fellowship, like Switch or Tank. What they don't understand is that --plotting their promotions in their corner offices while cutting back office supplies -- they're actually Agent Smith.

In 1999, we would have scoffed at the idea that our companies might be run by dastardly frontmen for a mysterious and all-encompassing ruler. We bought into the theory that the workplace hierarchy was flat -- even our bosses seemed chagrined to be in authority roles.

The stock market was roaring. We worked for companies that gave us flexible hours and a sense of empowerment we never thought possible in the corporate world. We were going to make history, change paradigms, and funk up the cube farms in some kind of Sandinista-worthy coup.

Instead, it's 2003 and we've taken the blue pill. For a few years, we had a glimpse of a reasonable workplace. Now we've gone back into the gray-green, soulless world of Metacortex, Thomas Anderson's software company. Neo doesn't work here anymore.

Can you even remember what 1999 felt like? Before W and the Florida elections? When "The Matrix" could call Morpheus a terrorist -- and no one would think of New York? Even back before Columbine, before this movie could be blamed for inciting suburban rage? Since then, much has changed for the worse, and "The Matrix" looks a little overused. Everyone from Mountain Dew to Missy Elliott employs "bullet time" to promote their products.

We've gone down the rabbit hole, and not in the way many of us expected.

The change, and our feelings about it, have very little to do with the evaporated wealth our stock options embodied. Most of us never expected to be able to pay off our student loans, much less retire at 30. Instead, these tech jobs showed us a world with a touch more self-determination than we ever expected to have while working for The Man.

We had it good for a while. Then the bubble popped, and so did our optimism.

Soon, we'll see if "The Matrix" has changed with us, the geek audience who treats the first movie like a sacred fable. In these new movies, I want each superhero to find a supermodel of his own (thus giving the programmer boys continued reason to hope).

I hope they escape the fluorescent boredom and dismal direction of "The Matrix's" world -- and I hope, in the real world, we do, too.

In real life, fans of "The Matrix" may be more Mouse than Morpheus. The past few years may have only brought us the occasional sidewalk Segway and a million Libertarian-flavored weblogs. We are returning to the mundane work world we thought we'd outsmarted. But we'll still check Monster.com every morning for a new lead. We're looking for the red pill: to wake from our dismal apartments (like Neo's own), with half-read books filling the corners of the room, and begin work on something truly worth doing.

Shares