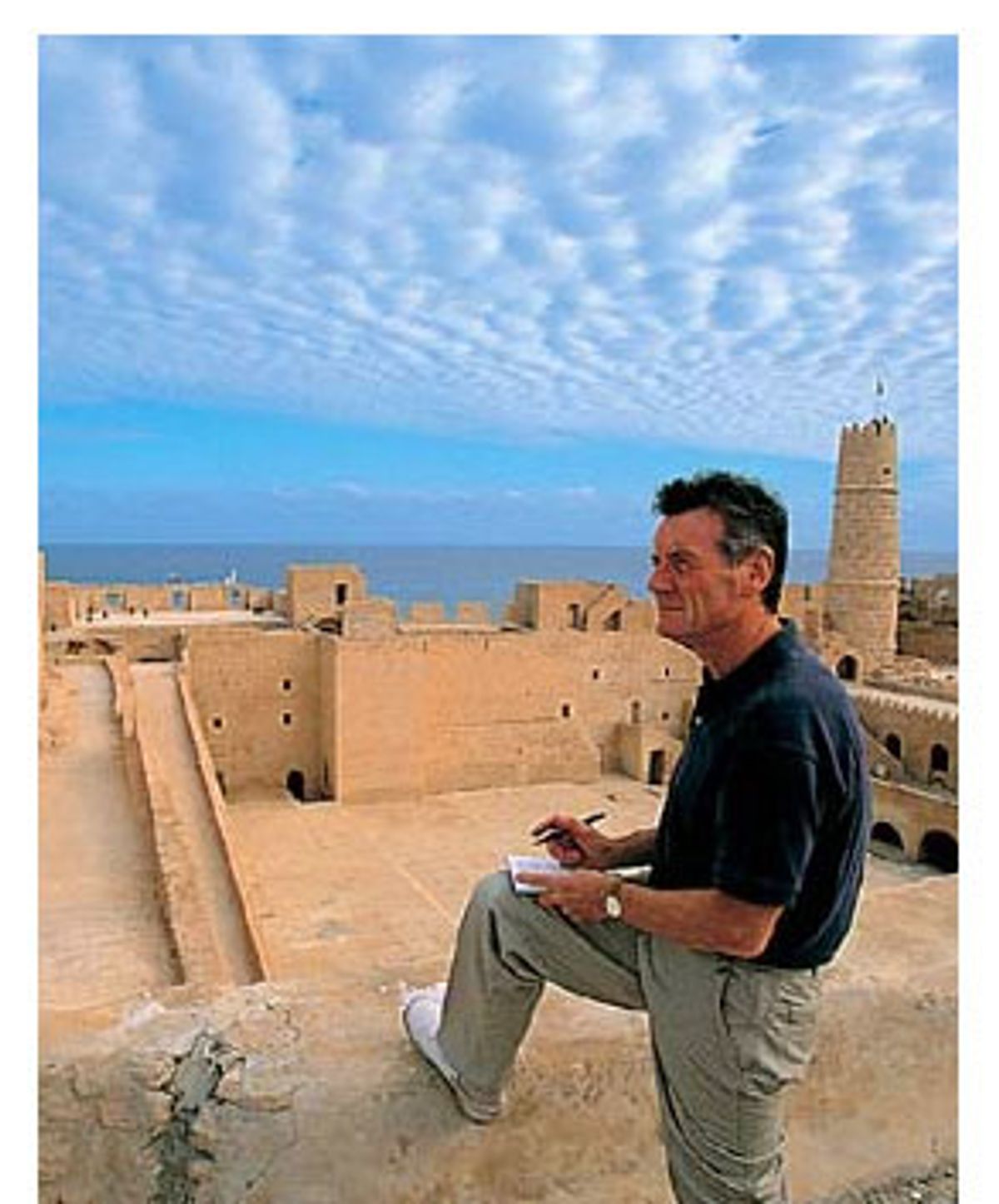

The last time we saw Michael Palin in the African desert, he was nailed to a cross -- in a movie, that is: "Monty Python's Life of Brian." Some 24 years after crooning "Always Look on the Bright Side of Life" while crucified alongside fellow Pythons John Cleese, Eric Idle, Terry Jones and Graham Chapman on a location shoot in Tunisia, Palin has returned to Africa for his latest in what's now a long line of televised travel series and books: "Sahara."

Although on previous journeys Palin has circumnavigated ("Around the World in 80 Days") and bisected ("Pole to Pole") the globe, ventured round the Pacific Rim ("Full Circle"), and retraced the multi-continental whereabouts of his favorite writer ("Hemingway Adventure"), "Michael Palin's Travels: Sahara" is in some ways his most ambitious effort yet. (The series airs on Bravo through June 1 -- check local listings -- and will soon be available on DVD. The accompanying book was published last month by St. Martin's Press.) After all, this is the most unforgiving natural environment on earth, and the journey comes at a time when Westerners (especially Britons and Americans) are not very popular in the Islamic world. And yet Palin still has time to cheerfully barter for yellow slippers in Morocco, watch a sheep sacrifice in Mali, play a marbles-like game using camel droppings in Mauritania, survey ancient Roman ruins in Libya, and trek for weeks without even a road to follow.

Of course Palin's travel series are but one component in an incredibly diverse career that started with what's easily the best comedy troupe of the last 50 years and that has seen him incarnated as a comedian, actor, novelist, playwright and political activist. Hell, he even demonstrated how to make homemade sausage during an appearance on "Late Night With David Letterman." Ever smiling and witty, Michael Palin gives dilettantes a good name.

More than that, Palin is also simply a nice guy, full of boundless good nature and optimism, whether his boat has run aground in Timbuktu or he's enduring yet another fan who wants to talk about a Python sketch from three decades ago. That's right: Michael Palin always looks on the bright side of life.

What's the most remote place you've ever been recognized as a member of Monty Python?

It did happen on a small island called Little Diomede in the Bering Strait, between Russia and Alaska. It's an utterly remote place, just a rock in the ocean with about 60 Inuit Eskimos who live there. Some Eskimos were gathered to take us across the strait in this whaleskin canoe. As we embarked to get on board, there was this clearing of throats, and I thought I was about to get this sort of Eskimo farewell or something. In fact, one of them points at me and says, "Hey! Aren't you the guy from 'Monty Python and the Holy Grail'?" They apparently had just seen the movie on satellite two nights before.

Is the Python legacy ever a burden to you, always having to smile when someone mentions a skit you've already heard about a thousand times?

Yes, it does happen, but I wouldn't say it's a burden. It's a tremendous relief, and quite a pleasure, that Python is still remembered. We thought it would be fairly transitory and replaced later by some other comedy show. I love that it's endured. Unfortunately, though, people expect me to remember all the sketches, and I never do. None of us do! I think we were at the Aspen Comedy Festival and there was a Python quiz they held. Even with all of us together, we couldn't get more than 60 percent right.

I must say that while watching "Sahara," I kept expecting you to stumble over a sand dune toward the camera and say, "It's..." like you did at the beginning of almost every "Flying Circus" episode.

It's very much "It's" territory. I remember the very first one on "Flying Circus." I scrambled out of the sea and up the sand of the south coast of England. And of course you may remember Python did a sketch called "Scott of the Sahara," a remake of "Scott of the Antarctic" in the Sahara. The leading actor had to act out of a trench because he was too tall for the love scenes.

Is there anything on your travels you've been asked to do and said "No way"?

The only thing I've ever refused to do is bungee-jump. That was in New Zealand. I'd just passed my 50th birthday, and I thought, "I don't need this." To plunge headfirst into the gorge wasn't very tempting. There are other things I've never wanted to do, but have always been persuaded by the director that it would be quite good if I had a go at it. Particularly with food -- I've eaten some very strange things. Food is used as a welcome; it's quite rude to turn it down. So I've eaten some odd things indeed.

Did you really eat camel in the Sahara? How does it taste?

Sure! There isn't much else to eat in these refugee camps of Algeria. It was actually very nice the first night, and then after about four nights it becomes slightly repetitive. Everything's supposed to taste like chicken, but it didn't in this case. It's sweetish meat, more like mutton.

How did Sept. 11 and its aftermath affect the filming of "Sahara"?

We were actually filming out in the desert on 9/11. We were in one of the most inaccessible places, a town called Agadez in the heart of Niger. We'd hear from BBC News and I talked on a satellite phone to my family at home. But it's very, very poor and they don't have newspapers and magazines, and there were no televisions where we were. All you could do was just imagine from these images what you'd heard had happened. I had a couple nights of very bad dreams.

After that, I thought, "That's the end of this series." But it was quite the opposite. The people in Algeria actually asked if we would come to their country. They said, "Now you'll know what we've been going through for 10 years with our own extreme radical Islamic movements here." And to a certain extent, for a while, it did make things better. We had no problems after 9/11, no problems after the Afghanistan bombing, anywhere that we went.

It's a good time for this series now -- a chance to humanize the people of Islamic countries whom it's all too easy for Westerners to vilify.

I think it's a way of looking at the world that tends to disappear in times of war. You tend to forget that the people hit by collateral damage are the sort of people I've met on my travels, people who are immensely tolerant, hospitable and proud of the lives they're leading. To me the saddest thing about war is that people like that, who we're trying to help, are the ones whose lives are ending. When I travel it really comforts me how little actually divides us. Of course there is a huge gulf in our material welfare, religious upbringing, and things like that. But things like your family, your house, your children's education, your hope for the future, are things that throughout the Muslim world they would share very easily with their counterparts in America.

Do you view the United States with the same sense of wonder as exotic locations in your specials, or does it feel more like home?

New York I feel quite familiar with, and I like Chicago very much. I also know a few people in L.A. But in between I don't know a great deal about. I spent some time in Montana recently, and that was such a different sort of land out there. It's just ridiculous the size and scale of it, but also there's still this kind of frontier spirit and mentality out there. So there are some places where I feel reasonably at home and the rest is a discovery to me.

Your feelings about the world really come through in your travel writings and shows. How do you balance expressing yourself and advocating for what you believe with not getting preachy?

I try not to preach. I realize some people are extremely good with arguments and can put them very cogently. I'm not very good at that. I'm a rather instinctive person. I know if I feel something is wrong, but I can't always express exactly what the alternative might be. I have to be the way I am. It's a bit like doing the travel programs. I'm being myself. That's what makes it work: People are aware this is not some expert trying to make judgments. It's just the way someone is. In public life I like to get involved with things where I can directly influence the outcome of something, where I can be involved with a small group of people and make it work. I don't particularly like being a name on a huge list.

You have traveled all over the world and left your wife at home. Is she jealous?

No, my wife is not an adventure traveler at all. She likes to get to a place, preferably with a lot of sunshine, and stay there for a week -- not immediately go climb the mountain or find the nearest headhunter and interview them. But she's quite happy to let me go as long as I come back.

There's a chat room on your "Palin's Travels" Web site in which a lot of women seem to talk about how sexy you are. How does it feel to be a sex symbol at nearly 60?

It's kind of weird. All I can say is, it's about 40 years too late. At the time I really wanted to be treated like a sex symbol, there was not a whisper. Now? Oh, great, some 18-year-olds think I'm sexy. I'm very pleased to be thought sexy by anyone.

What do you think of the explosion in travel literature and shows?

It pleases me when I see a few more shelves at the bookstore devoted to travel. It used to be down on the bottom with gardening and erotica. And I think some of the best modern writing comes now from travelers. This is a golden age of travel again. So many more places are available to us now, especially after the collapse of communism.

You've been a comedian and an actor, and you've written a novel, a play and children's books. What's your true love?

I suppose I enjoy writing most of all. It's something that I'm still always learning. I always felt the great thing about Python was that we wrote all our material. Acting to me is always subordinate to that. And when you're writing while you travel, it really concentrates your mind on what you're seeing.

Shares