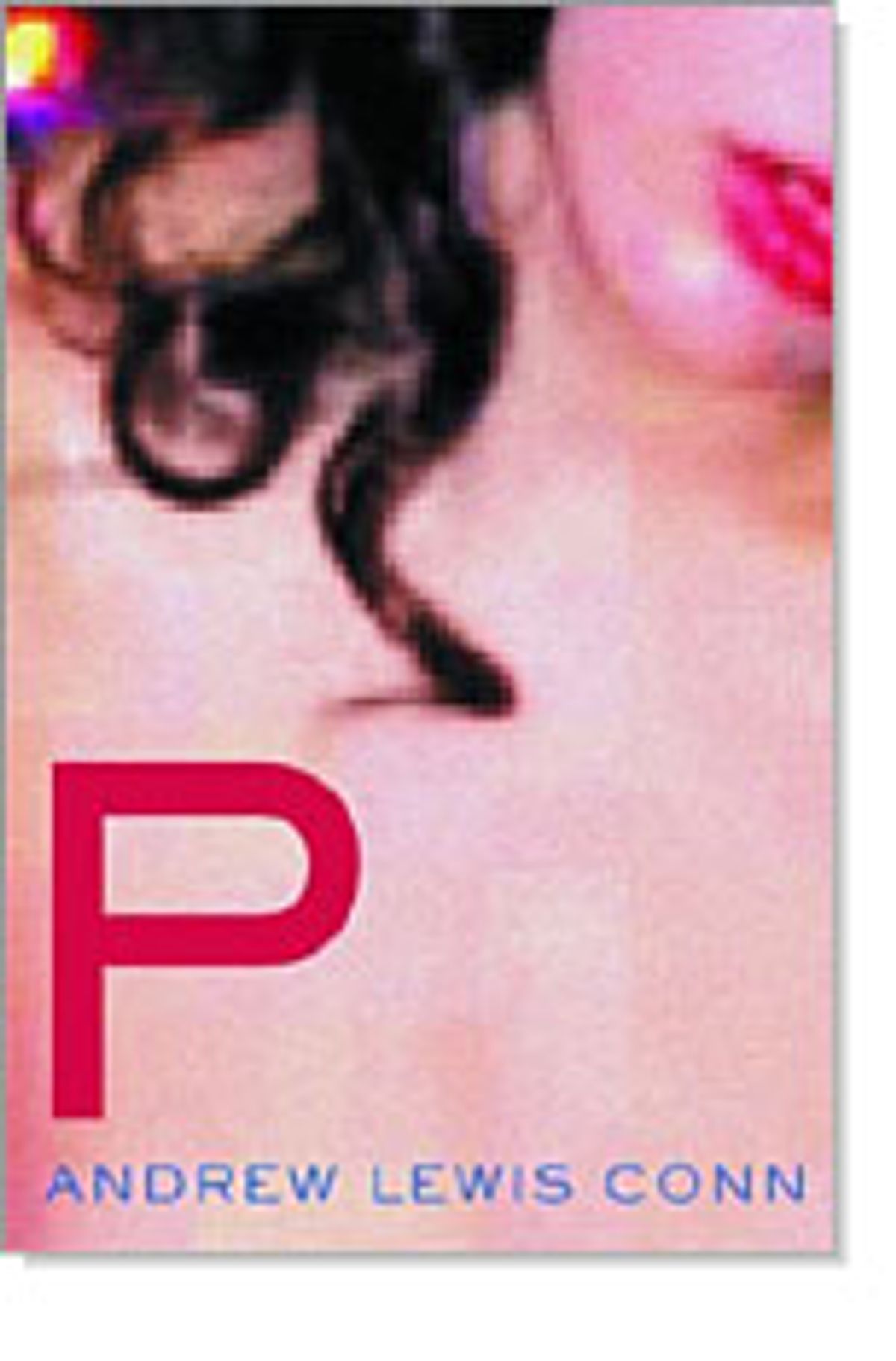

If Andrew Lewis Conn's debut novel "P" invites comparison to "Boogie Nights," it isn't just because Conn's protagonist, Benjamin Seymour, is a pornographer. Like Paul Thomas Anderson's film, Conn's novel is a young man's declaration of wild ambition, an attempt to distill every cinematic and (in Conn's case) literary reference he can in the course of telling his story. "P" isn't just Conn's "Boogie Nights," it's his "Zazie" (and you get the feeling he'd be happy with a comparison to either Raymond Queneau's novel or Louis Malle's film), his "Ulysses" (yes it is yes), the product of too much time in the video stores and the bookstores. It's a "Lookee what I can do, Ma!" performance, and often its brilliance is inseparable from what makes it maddening. But there's no doubt you're in the presence of someone with undisciplined talent, and the book's very immodesty is its saving grace. Please, God, give me young writers who put themselves on the line rather than those who take refuge in the exquisitely sculpted dead sentences they learn in graduate programs and writers' colonies.

Like "Ulysses," "P" takes place over the course of a single day. Nineteen ninety-six Manhattan substitutes for Dublin here and Benji Seymour is Conn's Leo Bloom. A 33-year-old porn producer and former actor hanging on in New York years after the bulk of the porn business has moved to the San Fernando Valley, Benji mourns his lost love Penelope Pigeon, the college sweetheart who entered porn with him and got lost to drugs and the vicissitudes of the business itself. The book's other main character is Finn, a 10-year-old runaway whom Benji encounters and makes it his mission to return to her mother.

Unfortunately, as that description implies, "P" is the story of Benji's salvation and, as it is in so many books and movies, the concept of salvation never quite loses its maudlin side. There are times reading "P" when you suspect that the book's stylistic showmanship -- it includes straight narrative, a section where each bit of action is preceded by headline summaries, a hundred-plus-page film script, a section modeled on a philosophical Q&A, and a parody/homage to Molly Bloom's monologue that closes "Ulysses" -- is aimed at disguising the basic triteness of the story. It's not that Conn is wrong in his assumptions about how porn uses people up and spits them out, or wrong to detect a certain glibness in the free speech/feminist/libertarian arguments that have been devised to defend it. It's that we've heard this story too many times before, in TV movies, on Ricki and Jerry et al., in journalism from the likes of David Foster Wallace and Martin Amis. And when you get to the bottom of the book, it feels as if you've been served a rococo bowl of matzoh ball soup, something familiar and comforting laid before you in a presentation elaborate enough to disguise the ordinariness of it.

And there are times when "P" becomes too much of a performance. The most elaborate section of the novel -- the screenplay -- is also the weakest. It obscures the relationship between Benji and Finn when we want to zero in on their wary interchange. And there are too many times when Conn goes off on needlessly showy tangents. In the Q&A section, which may be the book's most moving, we don't really need digressions on how light fills a room or how feces are formed. Conn has an affinity for the scatological but not yet the abandon to make it exhilarating. And his semi-disguised component portraits of figures like Andrea Dworkin, Leonardo DiCaprio, Al Goldstein, and (I think) the porn actor turned director Paul Thomas, feel more like Mad magazine spritz than satire.

What sustains "P" is the wildness of Conn's imagination, his willingness to go too far (even though that's accompanied by self-consciousness). A portrait of what it's like to walk through Manhattan on a hot summer day, a thumbnail sketch of the teeming yet featureless streets around Penn Station and Madison Square Garden, details of the smells and grit of the city, and minor figures like a born-again passing out literature, a young dot-commer on rollerblades, a discount drugstore clerk who wonders about Benji's persistent purchases of macadamia nuts (snack) and hand lotion (masturbatory lubricant) -- all of this accumulates into a feeling that Conn has managed to capture life in these pages. The portrait of New York that emerges from "P" might be called fervently ambivalent; Conn is as appalled by the city's noise and dirt and its capacity for alienating its inhabitants as he is energized. It's in this portrait that Conn shows a novelist's need not to settle for easy answers.

Many first works can't help showing their influences -- and even Conn's joking acknowledgment of those influences can't hide his debt to them. But there is enough in "P" that is real, that is felt, and that is observed to make you think you are experiencing the genesis of a very talented novelist. "P" passes a very crucial test: Putting it down, as irritated as I was enthralled, I had no doubt that I'll read Conn's next novel in a heartbeat.

Shares