It hasn't been a good year for Mormon public relations. In March, Elizabeth Smart, a 14-year-old Salt Lake City girl who had been abducted nine months earlier, turned up in the custody of a man calling himself Immanuel David Isaiah, an itinerant Mormon fundamentalist who had kidnapped her to make her his second "wife." Although the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS) is adamant that isolated fanatics like Brian David Mitchell (Isaiah's real name) and the more established but often equally bizarre fundamentalist communities scattered throughout the Southwest, Canada and Mexico are not encouraged by Mormon officialdom, to many the distinction seems only a matter of degree. When police first discovered the girl with Mitchell and his legal wife, she denied being Elizabeth Smart for nearly an hour, and more than one commentator observed that her Mormon upbringing made her a ripe candidate for the brainwashing Mitchell subjected her to. Despite the church's squeaky-clean image, polygamy and violence are deeply entwined in the roots of the Mormon religion, as no less than three books published this summer attest.

The most prominent of the three, "Under the Banner of Heaven," is the work of Jon Krakauer, whose account of the disastrous 1996 Everest expedition, "Into Thin Air," became a huge bestseller five years ago. "Banner" seems unlikely to repeat that success -- it lacks the breathless, minute-by-minute chronology of hubris, error and icy death that made his earlier book a stay-up-all-night read -- but the author's reputation should win it a large enough readership to dismay the official LDS, whose leadership has already issued a rebuttal. "Banner" is a mixture of true-crime reporting and history, centered on the grisly knife murder of 24-year-old Brenda Lafferty and her 15-month-old daughter Erica in American Fork, Utah, in 1984. The culprits were her two brothers-in-law, Ron and Dan Lafferty.

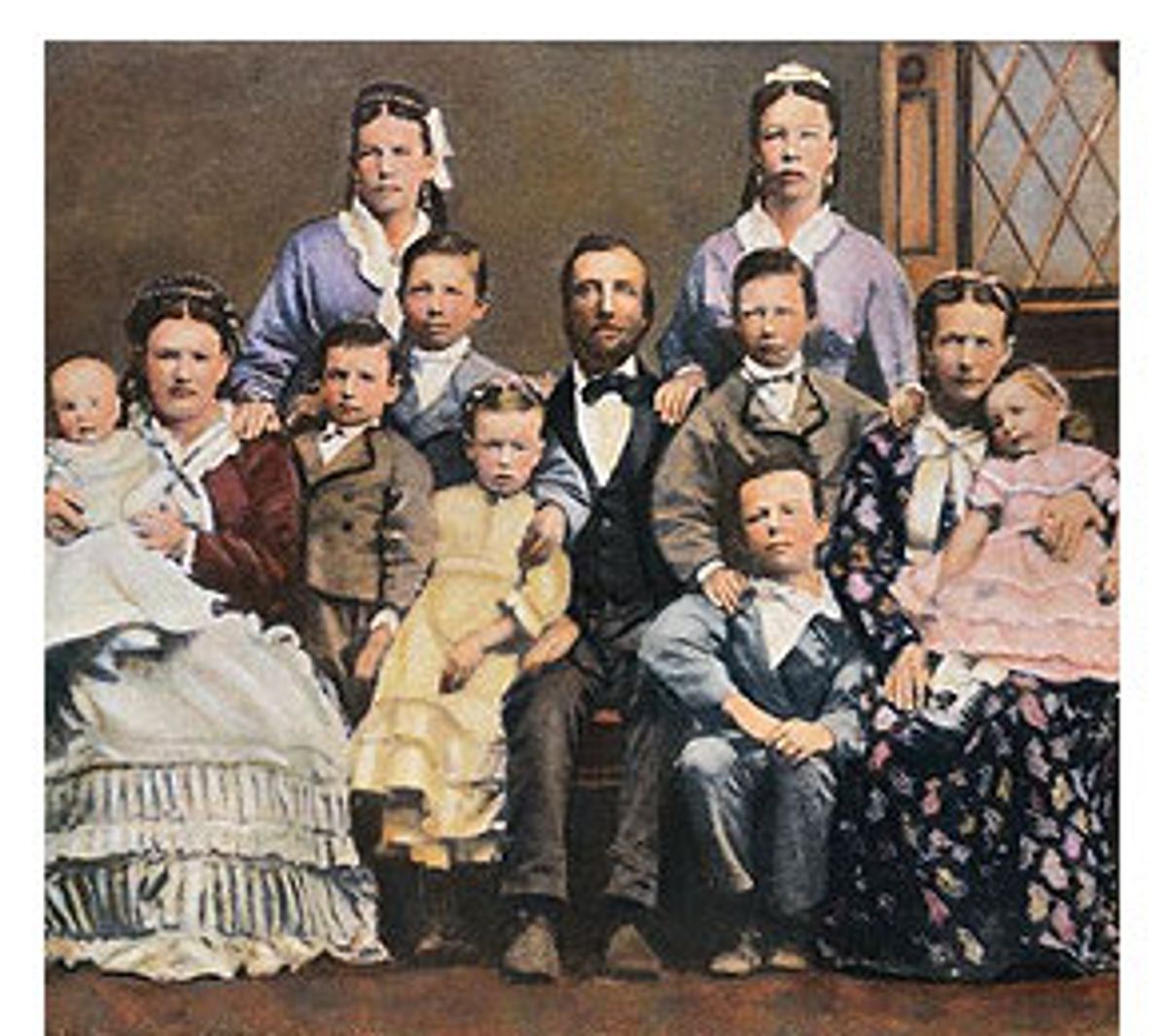

The Lafferty brothers had been excommunicated from the Church of the LDS for advocating a return to the ideal of "plural" or "celestial" marriage (polygamy) -- officially banned by the church in 1890 -- and then kicked out of a fundamentalist sect for presenting a divine revelation ordering that their sister-in-law and her baby (along with two other adults) be "removed." The sect, run by a 74-year-old man calling himself the Prophet Onias, had in turn splintered off from another group of zealots, the United Effort Plan or UEP, when Onias received a revelation that the men running the UEP had "gone astray." The leaders of the UEP also claimed to be operating their authoritarian polygamous community according to God's hand-delivered instructions, as did the original founder of the LDS, the prophet Joseph Smith, who received regular directives from above, including the proclamation known as Section 132, which declared that "If any man espouse a virgin, and desire to espouse another ... then he is justified; he cannot commit adultery for they are given unto him." (In fact, the right to multiple wives didn't accrue to "any man," but only to leaders of the church and a favored few on whom they bestowed that particular blessing.)

As Krakauer points out, the problem with a religion founded on the idea that its leaders get their marching orders straight from the Almighty is that members who quarrel with how things are being run have a tendency to start receiving their own contradictory commandments. That's why there are around 200 Mormon splinter groups throughout North America -- impressive in a religion that's not even 200 years old. Polygamy is the main point of contention between fundamentalist Mormons who wish to return to "the principle" and the U.S. government; it also makes for the most deliciously lurid headlines, especially when a camera hog like the "independent" (i.e., unaffiliated with any sect) Utah polygamist Tom Green comes along. Green had a penchant for going on national television to tout his multiple marriages, some to underage girls, and as a result provoked the authorities to convict him of child rape, bigamy and criminal non-support of his family. (The extensive Green household was largely bankrolled by state and federal welfare agencies.)

But as Krakauer's book, Dorothy Allred Solomon's memoir of growing up rebellious in a polygamist clan, "Predators, Prey and Other Kinfolk," and journalist Sally Denton's "American Massacre" -- a historical account of the darkest moment in Mormon history, the Mountain Meadows massacre of 1857 -- indicate, polygamy may not be the most troubling aspect of the religion. There's also the doctrine of "blood atonement," which holds that when a person is in a state of grievous sin, any Mormon in good standing who kills that sinner according to the proper protocol is actually doing the victim a service, cleansing the sin with blood. Of course, blood atonement has fallen into even greater disfavor with official Mormondom than polygamy has, but fundamentalists looking to terminate their enemies with extreme prejudice can find sufficient Old-Testament-style justification in the church's scriptural bedrock. Hence, the Lafferty brothers believed that they were cutting the throats of their sister-in-law and niece at God's command, and Solomon's father was murdered by an adherent of a rival sect leader.

The Lafferty brothers targeted their brother's wife because she'd been an obstacle to their efforts to "live the principle." Ron, the eldest brother and previously a loving husband and father and exemplary member of the LDS, became caught up in ideas detailed in a 19th century polygamist tract that he and Dan believed had been penned by Joseph Smith himself. Ron began to impose all sorts of onerous strictures on his wife, demanding subservience and a return to such frontier activities as churning all the family's butter by hand; he also talked about marrying off the couple's daughters as plural wives. Dan's wife, writes Krakauer, "was no longer allowed to drive, handle money, or talk to anyone outside the family when Dan wasn't present, and she had to wear a dress at all times." Their sister-in-law, Brenda, successfully encouraged Ron's wife to divorce him, thereby provoking Ron's homicidal wrath. (Why the baby needed to die as well has never been particularly clear.)

Krakauer doesn't hesitate to call renegade Mormons like the Laffertys "American Taliban." It's true that, like fundamentalists of all stripes, they're lashing out at a modern society that has left them feeling increasingly powerless, overwhelmed and sidelined. In the words of author Karen Armstrong, they want to "resacralize an increasingly skeptical world." But those are lofty terms for what, on the ground, often looks like a garden-variety crisis of sexual confidence. Ron Lafferty's slip into fanaticism followed some serious financial setbacks that ate away at his sense of his own manhood by impairing his ability to provide for his family. And when the demands of Islamists in the Middle East and Central Asia are boiled down to essentials, they largely amount to anxieties about women, wanting to keep them locked up at home and their bodies shrouded, entirely dependent on and subject to their husbands and fathers, their chastity strictly and often brutally enforced.

This brand of sexually rooted religious hysteria can be deadly, but it's not the only sort of violence associated with Mormonism. In her blistering account of the infamous Mountain Meadows massacre, Denton accuses the leadership of the church, and in particular its head, Brigham Young, of culpability in the worst white-on-white atrocity committed in America until the Oklahoma City bombing in 1995. In 1857, a large and wealthy wagon train of God-fearing, law-abiding Arkansas farmers headed for California was ambushed in the foothills of southern Utah. As many as 140 people were slaughtered -- all but the youngest children, who were thought to be unable to relate the truth about the killings.

From the beginning, the official Mormon line on the massacre was that it had been perpetrated by Paiute Indians, but whispered reports that the Mormons themselves were responsible could not be squelched. Some of the more appalling details include the treacherous use of a white flag in order to persuade the travelers to surrender their arms so that they might be more easily butchered, the hacking to death of women and children, the looting of corpses and the abandonment of the bodies to rot in the open air. The surviving children were brought to live in homes run by their families' killers, where plural wives wore the clothes of their dead mothers and sisters. Investigators who visited the site several months later were horrified by the long hair of the murdered women strewn all over the meadow's bushes.

Denton's isn't the first or even the definitive account of the massacre, but it's probably the most inclined to damn the Mormon elite for it. She looks askance at any reports of Indian involvement, beyond a few mercenaries hired to round out the Mormon ranks. She scoffs at Brigham Young's claim that, when notified that the wagon train had been spotted, he sent a letter to the local militia commander, ordering that the emigrants be allowed to pass "unmolested." The letter, which disappeared, supposedly arrived too late to save the emigrants, but as Denton points out, even an order not to attack implies an already standing order to do so. Federal investigators soon determined Mormon responsibility for the murders, and one of Young's most trusted lieutenants was executed for leading the massacre, although just how high up the culpability went remains unsettled.

As horrific as the Mountain Meadows massacre was, it's hard to blame it all on religious zealotry. The local Mormons and militia who did the killing were partly motivated by greed, as, probably, was Young, if he did indeed order it. The church, which was the sum and total of civic authority in the Utah territory, was in financial straits, and the wagon train was reportedly laden with gold. Young also knew that the federal government had become increasingly perturbed by his control over the Utah territory; Americans back East were shocked and titillated by the practice of polygamy, but there was also the question of the sovereignty over the West. Young knew that President James Buchanan had ordered federal troops into the territory, seeking to assert secular control over what Young considered his own personal Kingdom of Deseret.

The Mormons had suffered persecution in a series of communities before their exodus to the Great Salt Lake Basin, so a certain portion of their paranoia was warranted. But then again, they had a tendency to provoke the kind of animosity that led to persecution. While it's no excuse for the bloody and unjust acts committed against members of the LDS by non-Mormons (labeled "Gentiles" by the faithful), Mormons made a habit of moving into and taking over small towns. There, according to Krakauer, they lorded their sense of spiritual entitlement over the Gentile populace and "engaged in commerce exclusively with other Saints whenever possible, undermining local businesses. They voted in a uniform bloc, in strict accordance with Joseph [Smith's] directives, and as their numbers increased they threatened to dominate regional politics." Until he was lynched by an angry mob of Gentiles, Smith expected that he would soon become the theocratic monarch of the U.S. and "believed that democracy and constitutional restraint were rendered moot in his own case." He ordered the destruction of an opposition newspaper's printing press and the attempted assassination of a former governor who had been one of the faith's enemies.

Even where the Mormons were initially welcomed, they eventually antagonized those who were there first, and so emigration to a place as remote and unpopulated as the Salt Lake region became inevitable. When even that isolation was imperiled, they behaved as many a tight-knit, hierarchical community has; the Salem witch trial hysteria, recently linked by historian Mary Beth Norton to the Massachusetts settlers' besieging by nearby Indian tribes, comes to mind. The wagon train waylaid in Mountain Meadows posed no threat of any kind to Mormon autonomy, but the church's habit of regarding Gentiles as somewhat less than fully human made it that much easier for its soldiers to mow them down and grab their belongings.

It will be tempting for some to blame the Mountain Meadows massacre and the misdeeds of the Laffertys and other fundamentalists on Mormonism, or on religion as a whole. But there are plenty of secular counterparts to these crimes, committed in Polish and Ukrainian villages during World War II, under the Cultural Revolution in China or in various African conflicts. They are incited in the name of everything from tribal allegiance to class war. Behind their exalted rhetoric and unusual doctrines, the early leaders of the Mormon Church were motivated by the same things that drive authoritarian leaders everywhere: the amassing of personal wealth, the ability to boss all the other men around, and the opportunity to have sex with as many 14-year-old girls as possible. Brigham Young, meet Mao Tse Tung -- you two have lots in common.

The kinds of societies such men set up, whatever ideology and hero-worship they're wrapped in, are breeding grounds for atrocity. The only appropriate word to describe them is one that's been nearly drained of meaning by the overblown rhetoric of political correctitude: patriarchy. Institutions like fundamentalist Mormon clans or 18th century Salem serve as a salutary reminder of what that word really means. A society that demands unquestioning obedience to its leader or leaders, as the Mormon Church did and still often does, is really just a macrocosm of the kind of family where the man of the house regards the women and children in it as his property to use as he sees fit; exactly the situation that tract that inspired the Lafferty brothers recommends. It's a short step from that to the belief that Big Daddy gets to wipe out the lives of any underling or outsider who interferes with the free exercise of his power. Whatever stirring words he comes up with as an excuse is beside the point. The guys to fear aren't just the ones who believe in a god, but the ones who think they're entitled to act like one.

Shares