This past summer the Film Society of Lincoln Center, the people who put on the New York Film Festival each fall, ran a festival of CinemaScope movies at its Walter Reade Theater in Manhattan. Among the selections was 1969's "Play Dirty," a war story that is exceptionally well directed (by André de Toth) and is also one of the most cynical and sour action movies imaginable. After the press screening for "Play Dirty," a colleague and I were talking about the irony of seeing it in the plush environs of Lincoln Center when, if we had been reviewing movies in 1969, we would have seen it in a 42nd Street grind house.

The grind houses are gone now that Times Square has been cleaned up by Disney, among others. But the spirit of the grind houses lives on in the art house. At least three or four times a year now, a foreign or indie movie appears whose main selling point is the same gore-and-sex combo that used to lure audiences into the grind houses. Theaters no longer pass out barf bags as they did for "Mark of the Devil," but the ads for Gaspar Noé's "Irreversible" made sure to mention the couple of hundred audience members who stormed out of the film's Cannes screening during the nine-minute unbroken-take rape scene. The gruesome climax of Noé's previous movie, "I Stand Alone," was preceded by a flourish right out of William Castle, a blinking red "WARNING!" sign that alerted moviegoers, "You have 30 seconds to leave the theater." Essentially, this is the same "Can You Take It?" come-on that exploitation producers used to promise grind-house patrons that their movie delivered the dirty goods.

Headlines were always good fodder for the grind house. But 30 years ago a movie like "Survive!" (about the Andes plane crash where surviving soccer players cannibalized their dead teammates) or "Guyana, Cult of the Damned" (about the Jonestown massacre) went straight to drive-ins and second-run houses. Today, Gus Van Sant's "Elephant," which is more or less about the Columbine High School shootings, wins the Palme d'Or at Cannes and is selected for the New York Film Festival.

"Elephant" is too austere, too formalized, to satisfy the exploitation crowd. Most of the movie consists of endless tracking shots, as cinematographer Harris Savides' camera simply follows characters through the (strangely unpopulated) halls of a suburban high school. What gives "Elephant" the air of an exploitation movie is the gut-squeezing sensation you get watching it. As in movies like "Boys Don't Cry" or "The Accused," "Elephant" exists in an atmosphere of queasy anticipation of the atrocity you know is coming at the end. And with the exception of one cafeteria scene, there seem to be only about 10 or 12 people in the entire school, so we know that the characters we're watching are the very ones who are going to get it. Sure enough, the massacre comes on schedule.

It would be crediting "Elephant" with too much depth to call it Van Sant's examination of Columbine. It's more like his Columbine art project. Van Sant's xerox copy of Alfred Hitchcock's "Psycho" seemed like nothing so much as a gigantic Cindy Sherman installation, and something similar characterizes "Elephant." The film has been described as naturalistic, but the look and the blankness of the atmosphere is very achieved. It may be true, as has been charged, that the French loved "Elephant" because it conforms to their idea of America as a mindless, gun-ridden charnel house. The movie, though, is too dead to be a diatribe.

Van Sant doesn't depict the suburban high school and middle-class homes with anything approaching loathing; he'd have to work up some passion before he could loathe anything. He and Savides are going for an avant-garde anthropological look. They shoot the interiors as airless dioramas. Van Sant gets something of the texture of high-school life -- the sense of suspended time, the boredom -- but he never goes beneath the surface. Compared to Frederick Wiseman's 1968 cinema-vérité documentary "High School" (which appears to have been one of Van Sant's models), "Elephant" offers nothing of the interactions of high school, the feelings of students trying to be themselves in the face of petty authority. This is the type of movie that inevitably gets praised as being a corrective to the Hollywood view of high school. But nothing in it rings as true as the best moments in "Fast Times at Ridgemont High" or "Carrie" or the early seasons of "Buffy the Vampire Slayer."

The cast of "Elephant" comprises actual high-school students with no professional acting experience, culled from various schools in Portland, Ore. They are not called on to give performances, because Van Sant isn't interested in exploring teenagers as much as in fetishizing them. The camera lavishes more attention on one boy's blond surfer hair, or on the clothes the kids wear, than on the kids themselves. The characters here serve the same purpose as the furnishings in the school and the kids' middle-class homes: They're static details in Van Sant's composed frames. This preoccupation with texture means that Van Sant has nothing to tell us about why events like Columbine happen.

To be fair, he's not required to do so, and any filmmaker who gives us reasons for the inexplicable risks trivializing it. In last Sunday's New York Times, Van Sant told Karen Durbin that assigning the blame for school killings to rap or video games is "a way of scapegoating ... The movie is about avoiding that, by just observing the last day, where you see evidence of different things that hopefully spur your own imaginings about the meaning of the event." But to successfully work in that way takes a richer, more articulate approach than Van Sant's faux naturalism allows for. Van Sant took the title of the movie from the late English filmmaker Alan Clarke's film on violence in Northern Ireland. Clarke said he meant the title to refer to the elephant in the room that nobody speaks of. If "Elephant" is Van Sant's way of talking about the roots of high school violence, it would have been better if he'd shut up.

It may be that he shows us a scene of one of the killers being bullied, or shows them playing violent video games and ordering guns from the Internet, or assembles them in front of a TV documentary on Hitler, for the express purpose of discounting those "reasons" as convenient excuses. But with no emphasis put on anything, with every scene given the same listless weight -- which is to say, no weight at all -- those scenes appear as warning flags. How else are we to interpret a point-of-view shot from one of the teenage killers mowing down characters on a computer screen, and then an exact repeat of the shot when he turns his gun on his fellow students? There is no other way to interpret it except as the character's inability to distinguish reality from video games.

"Elephant" is in a line of descent from "troubled teen" movies like "River's Edge" and "Kids," pictures that are designed to appeal to both the hipsters in the art house audience and Op-Ed writers who never miss a chance to bloviate on a pressing social problem. But there are moments where Van Sant goes well beyond alarmism and straight into a sort of mindless bigotry. If a straight filmmaker had shown us the two killers kissing in the shower before they embark on their killing spree, he would have been accused of using the old homophobic idea of gays as suppressed killers.

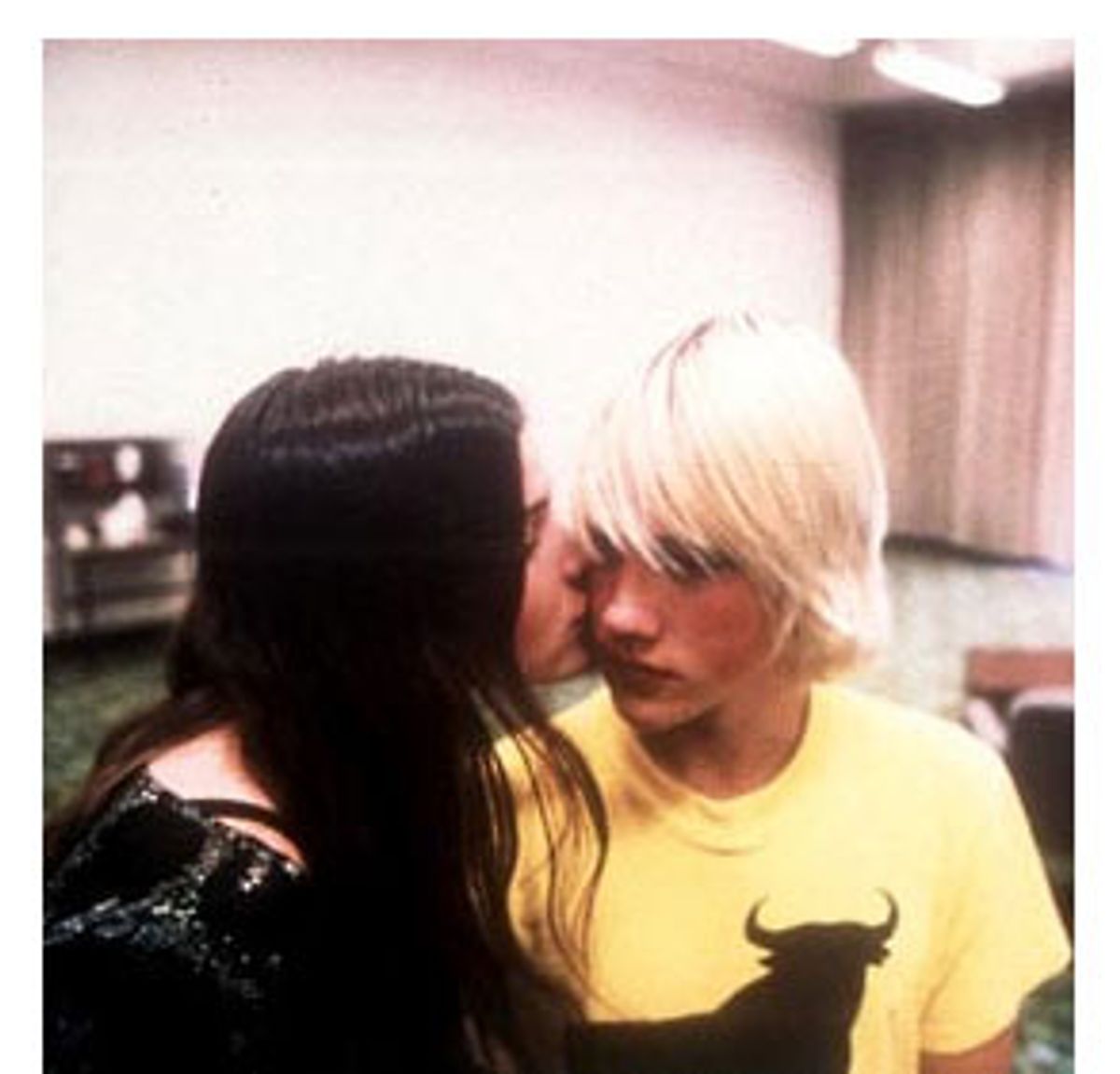

There should be plenty of ways to read the scene: as the two wanting some human contact before dying, as simple teenage experimentation. The kiss between the two boys in "Y Tu Mamá También" proved that two males kissing on-screen could denote something other than homosexuality. (What Alfonso Cuarón intended to say in that scene was that in the heat of the moment, sex is sex.) It's pretty clear that the only reason the kiss exists in "Elephant" is that Van Sant couldn't resist watching two teenage boys make out. The voyeuristic way the scene is shot -- through a fogged shower door -- emphasizes that. Again, because he stays so rigorously outside the characters, Van Sant has eliminated all potential meanings except the most obvious.

A straight filmmaker without Van Sant's indie cred (however much diminished by the likes of "Good Will Hunting" and "Finding Forrester") also wouldn't get away with the misogyny of a scene where we see three catty, popular girls pick at their lunch and then -- punch-line alert! -- go into the bathroom, where they make themselves vomit.

Such a director surely wouldn't get away with the treatment of the movie's sole black character. This tall, silent young man appears late in the movie to help kids scrambling out of a classroom window to escape the shootings. Then, for no discernible reason, he is drawn back toward the sounds of gunfire. Nothing in his face registers why he's going back; there's no indication of a determination to help, of morbid curiosity, of anything. He simply walks toward the sounds and, about a minute after he's been introduced, is shot dead. Van Sant may have intended a comment here on the expendability of black characters in movies, but he simply apes the conventions of the sacrificial black -- and with considerably less distinction than black supporting characters are allowed even in Hollywood junk. (Watching the scene, it's also hard not to think that school shootings didn't become a hot topic until it was white kids killing other white kids.)

There's a big difference between a filmmaker who sets out to resist easy judgments and one who simply reproduces events without putting any thought into them. When the killings eventually come they are shown to us in as blasé a fashion as everything else. Van Sant's defenders may claim that he's trying to show us the affectlessness of the teen killers. But depicting the attitudes of even the worst characters does not prevent a filmmaker from taking his own attitude toward them. It may look as if Van Sant is exercising discretion when two characters who have taken refuge in a meat locker back out of the frame and we see two hanging sides of beef while the kids are gunned down. But in Van Sant's scheme, the beef has as much distinction as the kids. This, I think, is what finally marks "Elephant" as a true exploitation movie. It's not that Van Sant is getting off on the killings or asking us to get off on them, but that he is simply using a real-life tragedy as fodder for his little art movie, and that he hasn't even done the thinking that would allow him to say there are no answers for these killings.

The moment that most sticks in my craw comes right after the first killing in the school library. We've watched one of the characters, an aspiring photographer, wandering the halls and grounds taking pictures of his classmates. Right after the first head goes splat, Van Sant cuts to this boy raising his camera and snapping a picture of the corpse.

Since no psychology is supplied for any of the characters or events here, the boy's sudden cynicism makes as much sense as anything else in "Elephant." But how did Van Sant have the stones to include it? When a director who has been trying to regain the art-house cachet he lost with a string of commercial projects makes use of the murder of high school students and then has the nerve to criticize a character for opportunism -- when he distances himself from actual violence and suffering and substitutes aesthetics for exploration -- it's not the characters on-screen who are divorced from reality.

Shares