Buoyed by the endorsements of the two largest unions in the AFL-CIO, Howard Dean seems likely to ride the wave of rank-and-file Democrats' anger at George W. Bush all the way to the party's presidential nomination.

Meanwhile Bush's handlers have devised a strategy designed to defeat Dean or any other hard-hitting opponent: benefit from a backlash against what they claim are extreme attacks against a sitting president.

Like a prizefighter hitching his trunks high above his waistline so that he can claim his opponent keeps hitting him below the belt, Bush's cornermen are already trying to get the Democrats disqualified as hateful partisans, even before he and his as-yet-unchosen challenger start squaring off.

The message that the Democrats are crazed with anger at Bush is reverberating through the Republican echo chamber. In a recent memo to party leaders, Republican national chairman Ed Gillespie attacked the Democrats as the party of "protests, pessimism and political hate speech."

Sounding a similar note in a fundraising appeal this month, Vice President Dick Cheney warned Republican donors to expect "fiery rhetoric" from the Democratic presidential contenders, including attacks on Bush's "character, his veracity, even the president's leadership of the war on terrorism."

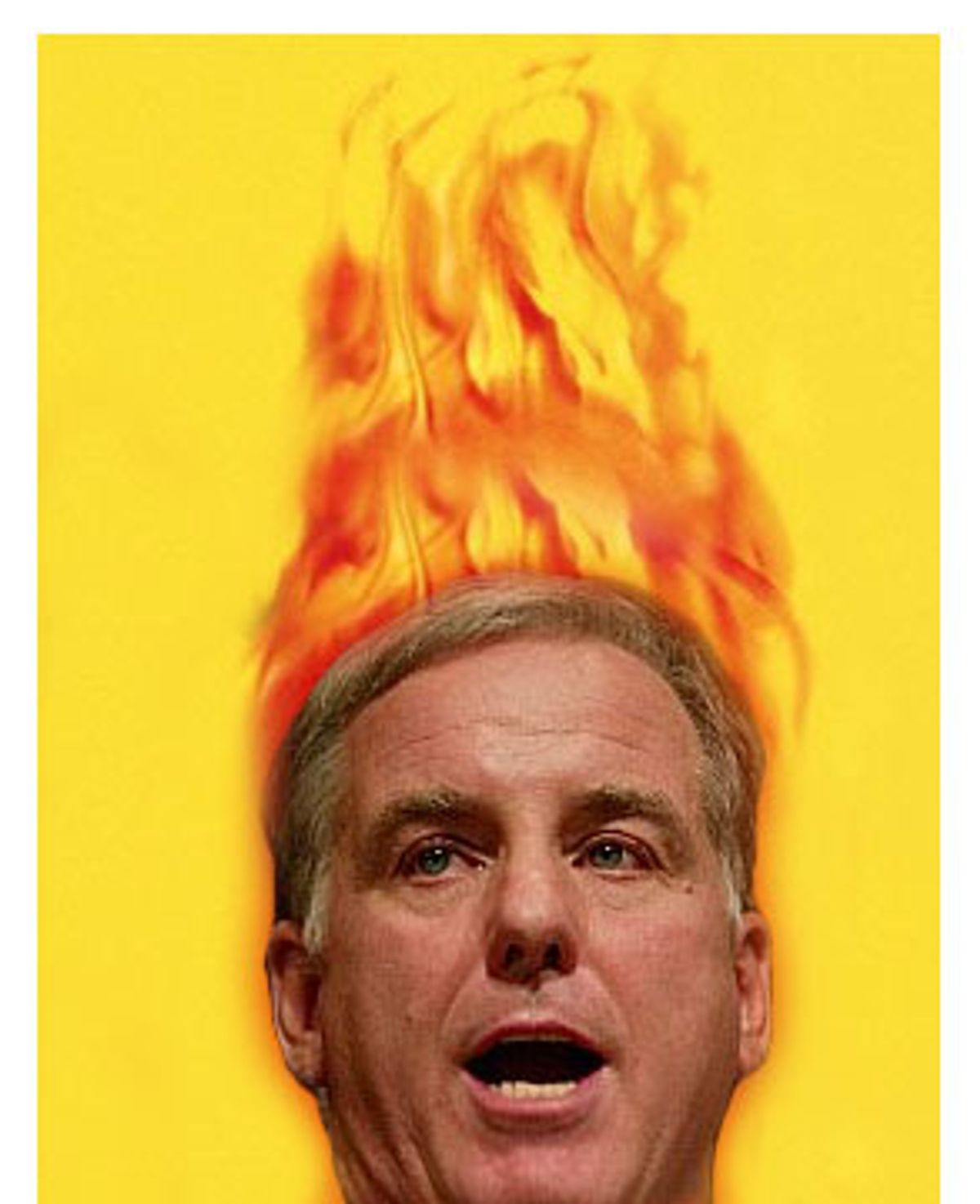

Last month, in response to a razzing by a heckler, Florida Gov. Jeb Bush called Dean the candidate for "hot, angry people that aren't rational and are screaming and hollering." Over the summer, the Weekly Standard did a cover story about Bush hatred, titled "The Democrats Go Off the Cliff," while conservative columnists from the New York Times' David Brooks to the Washington Times' David Limbaugh warned that the Democrats are too nasty when it comes to Bush.

All this suggests that Bush's backers are reading the same talking points: The president is a man of moderation beset by hateful partisans.

This strategy serves four goals: portraying Bush as the unifying leader that he could have become after the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001. Diverting attention from his own high-risk policies. Painting his eventual opponent -- especially if it's Dean -- as the real extremist and a hothead as well. And blaming Bush's lack of legislative accomplishments on the Democrats' refusal to work with a president they despise.

It's a shrewd strategy, worthy of White House political mastermind Karl Rove. And don't say Dick Cheney, Jeb Bush and Ed Gillespie haven't warned you.

But if the Republicans are tipping their hands, are the Democrats playing into their hands? Is Bush counting on driving the Democrats crazy, making them so angry that they're following his game plan?

Dean won Democrats' hearts, their dollars and, most likely, their votes, by becoming the first contender to take the gloves off against Bush. He kept saying: "The only way to beat this president is to go right after him." Impressed by the former Vermont governor's progress from footnote to favorite, the other contenders have been upping the rhetorical ante with red-hot rhetoric of their own.

The usually mild-mannered Midwesterner Dick Gephardt keeps calling Bush "a miserable failure." The sweet-talking Southerner John Edwards brands Bush "a phony." Combat veteran John Kerry calls for "regime change" here in the United States. Nice guy Joe Lieberman maintains a Web site about Bush's lack of integrity. The Rev. Al Sharpton compares Bush to a "gang leader," and U.S. Rep. Dennis Kucinich and former Sen. Carol Moseley Braun have offered epithets of their own. Only retired Gen. Wesley Clark has held his rhetorical fire against the commander in chief.

If any of the contenders worries about a backlash from all this Bush bashing, only one has said so publicly. In an interview this week with editors and reporters of the Washington Post, Edwards said: "It's true that you can get Democratic activists on their feet cheering much more quickly bashing Bush than any other way. But, remember, we're going through a process here that people are looking for a president. They're not looking for someone who can just beat up George Bush."

As long as the nomination remains undecided, all the contenders, including Edwards, will keep trying to "get Democrats on their feet cheering." Party activists have been applauding attacks on Bush and screaming for more. "Bush gets Democratic base voters very angry -- more even than Reagan," declares Democratic pollster Geoff Garin. That's because Bush ran as a moderate "compassionate conservative," won a disputed election, and proceeded to govern as a confrontational conservative, with three consecutive top-bracket tax cuts and a new doctrine of preemptive war. Also, if the Democrats are an uneasy coalition of the underpaid working class and the overpaid meritocracy, Bush seems genetically engineered to offend them all: a president's son who, by his own admission, stumbled through life until age 40, after which he acquired a baseball team, a governorship, the presidency, and an aura of unearned entitlement.

With nine contenders competing for the favor of any angry party membership in a primary season that's starting sooner and probably ending earlier than ever before, Bush bashing is smart politics. But is it the ticket to beating a sitting president who is most comfortable casting himself as an ordinary guy beset by overly aggressive adversaries, from Texas Gov. Ann Richards, who called him "Shrub" in 1994, to Vice President Al Gore, who hovered over him during their debates in 2000?

Sensing that the Bush campaign wants to benefit from a backlash against the angriest attacks on him, Democratic strategists are discussing how harshly and how personally to criticize him. It's a question of style, not substance, but, as defeated Democrats from Walter Mondale and Michael Dukakis to Al Gore and Gray Davis can testify, style matters, too.

Considering what Americans want in their president, many strategists are concluding the Democratic nominee needs to walk a tightrope on bashing Bush: Stress policies, not personalities. Don't be a passive fall guy, but don't be a pugnacious bad guy, either. Offer a positive vision for America's future. And leave the really rough stuff -- charges that Bush isn't up to the job, or that the administration lied the nation into war in Iraq -- to others.

While the centrist Democratic Leadership Conference counsels against attacking Bush personally, so do some on the party's left. "I don't think Democrats should engage in personal attacks on the president," explains Bob Borosage, co-director of the liberal Campaign for America's Future. "His personal failings are not nearly as striking as his policy debacles. People can like him and still know he's incompetent."

On the balancing act between being seen as pugs or patsies, Donna Brazile, who managed Gore's presidential campaign, explains: "We should not back down and not blink. But we should also learn how to disagree with people and still respect them. That is the only way to defeat your enemy."

Instead of focusing entirely on the thrust and parry of charges and countercharges, several strategists caution that, as pollster Geoff Garin observes, "the first challenge in an election against an incumbent is to make the case for change." Borosage adds: "The Democrats have to lay out what they're for. There's a real danger of just being a critic rather than a leader."

As for attacking Bush's competence or integrity, these strategists suggest that the Democrats try what Bush himself has done masterfully since he began his first presidential campaign in 1999: Let others make the harshest attacks. "It's a very different question whether the ultimate nominee ought to be making the most damning case or whether others in the party ought to," Garin says.

This strategy of going after Bush's policies, not his personality, flows from the fact that, unlike partisan Democrats, most Americans still like him. As with former Presidents Dwight Eisenhower, Gerald Ford and Ronald Reagan -- and unlike Lyndon Johnson, Richard Nixon and Bill Clinton -- more people like Bush personally than approve of the job he's doing. Even now that the polls show Americans are evenly divided about Bush's performance as president, his personal approval ratings are almost 10 points higher than his job approval, according to recent surveys by CNN/USA Today and the Wall Street Journal.

His good ol' boy manner made friends during the 2000 campaign and the first eight months of his presidency, but Bush truly bonded with Americans after the Sept. 11 attacks. "Bush is really well liked by people because he's been through a real crisis with folks, and they feel a real connection with him," explains Democratic strategist Will Robinson. "Just like attacking someone's friend, you have to be careful about attacking him. People are willing to give a friend who's in trouble a lot of latitude."

Going after a sitting president with a stiletto, not a sledgehammer, is also in keeping with the lessons of the past century of presidential politics, which Rove, a close student of history, has doubtless pored over. When it comes to defeating presidents for reelection, treating them contemptuously may be emotionally satisfying for their opponents. But it isn't a winning political strategy.

In fact, as Georgetown University historian Michael Kazin explains, presidents "gather strength from the other side's hatred" because it intensifies their own support and antagonizes Americans who respect the presidency even if they question an incumbent's policies.

In modern times, the presidents whose opponents despised them most vocally and viciously -- Franklin D. Roosevelt, Richard Nixon and Bill Clinton -- were reelected by landslides. They turned their adversaries' antagonism into an asset by turning the electorate against their most intense opponents -- the "economic royalists" who jeered FDR, the student protesters who marched against Nixon, and the "vast right-wing conspiracy" that tried to impeach Clinton.

As for the presidents who were defeated for reelection -- Gerald Ford, Jimmy Carter, and George H.W. Bush -- they weren't despised by the voters or demeaned by their opponents. And the challengers who beat sitting presidents -- candidates Carter in 1976, Ronald Reagan in 1980, and Clinton in 1992 -- avoided attacking the incumbents intensely or personally.

In 1976, Carter beat Ford by killing him with kindness. Promising "a government as good and decent as the American people," Carter never attacked Ford for pardoning Nixon, his disgraced predecessor. Four years later, in the midst of recession, inflation and the Iranian hostage crisis, Reagan beat Carter without ever attacking him personally. Reagan's pollster, Ronald Wirthlin, cautioned in a memo: "Care must be taken so that the Governor's [Reagan's] criticism of Carter does not come off as too shrill or too personal. We can hammer the President [Carter] too hard, which will spawn a backlash ... The Governor must never attack Jimmy Carter's personal integrity." In 1992, Clinton won the nomination against several rivals who attacked the first President Bush much more harshly than he did, including Iowa Sen. Tom Harkin, who said, in his stump speeches: "George Bush has feet of clay, and I'm going to take a blow-torch to them."

In his speech announcing his candidacy, Clinton declared: "We're not going to get positive change just by Bush bashing. We have to do a better job of the old-fashioned work of confronting the real problems of real people and pointing the way to a better future." In the primaries and in the general election, Clinton did something none of this year's Democratic contenders are doing: He expressed empathy with the plight of people "working longer and harder for less" and explained how government could help them improve their lives.

"Very little of what Clinton said was attacking Bush," recalls former White House press secretary Dee Dee Myers, who traveled with Clinton during the 1992 campaign. "The tone was, 'We all know President Bush is a decent man. But he is just misguided on the economy, healthcare, and what life is like for most Americans.'"

But can the second President Bush be beaten the same way the first one was? Or is the only way to defeat this Bush to demolish the personal credibility that has been at the core of his appeal but could be his greatest vulnerability? The case has been made -- implicitly by Dean and explicitly by Gore -- that Bush is different from previous presidents, particularly his father, and must, therefore, be challenged differently.

Few Americans believed that Bush I was personally to blame for the recession or other problems during his presidency, much less that he was lying about them. They just thought he didn't have a clue about how to solve those problems.

But Bush II is very different -- or so this analysis argues. While his father seemed clueless about how to solve the nation's new problems, the younger Bush always has an answer. The trouble is, it's an answer that he -- and his conservative base -- favored long before the problem emerged.

Bush has always wanted to cut the taxes of wealthy people, so he justified the tax cuts first because the nation could afford them when the federal budget was in surplus and then because the nation needed it when the economy was in recession. He always wanted to remove Saddam Hussein, so, after Sept. 11, his administration kept suggesting that Iraq had weapons of mass destruction and was working with al-Qaida, however shaky the case for both claims.

Just as his solutions fit any crisis that comes down the pike, so does Bush always seem able to find facts to make his case. Summing up this analysis of why Bush is deceptively dangerous, Gore told the Internet-based liberal activist group MoveOn.org: "The president seems to have been pursuing policies chosen in advance of the facts" and is making "a systematic effort to manipulate the facts in service to a totalistic ideology that is felt to be more important than the mandates of basic honesty."

If Gore is right, then maybe, just maybe, the best way to challenge Bush is to "go right after him," as Dean promises to do. Challenge his premises as well as his policies. Make the voters look behind Bush's friendly smile to see his extreme agenda and his habit of making up the facts as he goes along.

But this battle plan is problematic against any president -- especially a personally popular one. It's one thing to convince the voters that Bush's policies are a failure -- even "a miserable failure," as Gephardt keeps saying. It's a little tougher, but still possible, to make the case that Bush's policies are based on faulty facts. But, as the trial lawyer Edwards could remind his rivals, it's much more difficult to prove that Bush's policies are based on deliberately falsified information. And, as today's Democrats can learn from studying the fates of Ford, Carter, and Bush I, who remained respected but weren't reelected, they don't have to destroy Bush II personally in order to defeat him politically.

Dean himself may well understand this. Careful planner that he is, he could well be sketching out his general election campaign already. He previewed his appeal to the entire electorate with his formal announcement speech in his hometown of Burlington, Vt., in June, emphasizing positive themes of empowering Americans to defend their democracy against wealthy special interests and secretive preemptive warriors. He refined this rhetoric in a rare formal, prepared address in Boston last month, suggesting that the survival of American democracy is at stake next year and the grassroots movement supporting him is in the tradition of patriots who have preserved democracy in the past.

So Dean has both the message and the policy agenda to make the case to the undecided electorate that he can solve problems Bush can't. The challenge for the feisty front-runner is to present those policies with optimism more than anger, and to strike the right note when it comes to the president. As long as he's fighting for the Democratic nomination, that could be difficult, since the Bush-hating base may prefer Angry Howard to Dignified, Optimistic Howard. But if he wraps up the nomination early, he'll have time to modulate his appeal.

While bashing Bush is emotionally satisfying for some, beating Bush requires making a more reasoned and positive case. For angry Democrats, next year's strategy could be summed up this way: "If it feels good, think twice before doing it."

Shares