"Michael Stipe ate a Whopper. Pass it on."

That was the sarcastic remark a buddy of mine used to make whenever he could take the obsessive cult of R.E.M. no more. From the moment the Athens, Ga., quartet released their first EP, "Chronic Town," in 1982, anyone attuned to the ragtag world of alternative rock (or progressive or modern or underground rock -- the labels were still in flux) felt a seismic shift in the musical order of things, a disturbance in the force of the aural kind.

Other independent acts had made inroads by then, sure. The wonderful Los Angeles punk band X shocked the music industry by shifting 80,000 or so units of their essential 1981 album "Wild Gift" on the low-rent Slash imprint, and R.E.M.'s fellow Athenians the B-52s had already made a much-ballyhooed appearance on "Saturday Night Live," slaying the studio audience (and much of late-night America) with a deeply weird rendition of their party-startin' classic "Rock Lobster." A slew of adventurous British acts had broken through by then, too.

But R.E.M. were different. They were less a band, it seemed at the time, than a phenomenon. A subcultural force with the aesthetic equivalent of gravitational pull, the group brought a far-flung sonic universe into a kind of rough orbit. It helped that in interviews with fanzines and more widely circulated publications such as the late, great Trouser Press, the band members (guitarist Pete Buck, bassist Mike Mills, drummer Bill Berry and frontman Stipe) dropped a gazillion names, groups their acolytes quickly filed for future reference: Hüsker Dü. The Replacements. The Minutemen. Meat Puppets. Love Tractor. Pylon. For aspiring hipsters -- and certainly for all record-store geeks -- articles about R.E.M. were basically required reading: They were veritable Cliffs Notes of coolness.

So it's hardly surprising that a movement of admirers and imitators quickly coalesced. In Orlando, Fla., where I was living at the time, the best record store in town was dubbed Murmur, and not one but two bands on the local scene lifted their names from R.E.M. tunes. (One even began life as a straight-up cover band.) Another outfit, a group that was more likely to cover "Cruel to Be Kind" than "Radio Free Europe" whenever they played live, felt obliged to make a pilgrimage to Winston-Salem, N.C., to record their debut disc with Mitch Easter, leader of contemporary jangle rockers Let's Active and producer extraordinaire of "Chronic Town" as well as R.E.M.'s next two (and still-amazing) albums, 1983's "Murmur" and 1984's "Reckoning."

So Michael Stipe ate a Whopper indeed.

Still, oversaturation and adoring music nerds aside, it was virtually impossible not to be charmed to the point of seduction by R.E.M. With ample assistance from Easter, the band made lush and sensuous music, cranking out records fueled in large part by Buck's Byrds-like arpeggios and Stipe's incoherent (but lovely) mumbling. That latter trait in particular was one of the group's huge hooks: Southern-accented phonemes hung on melodies so large they basically dared you to write your own damn poem.

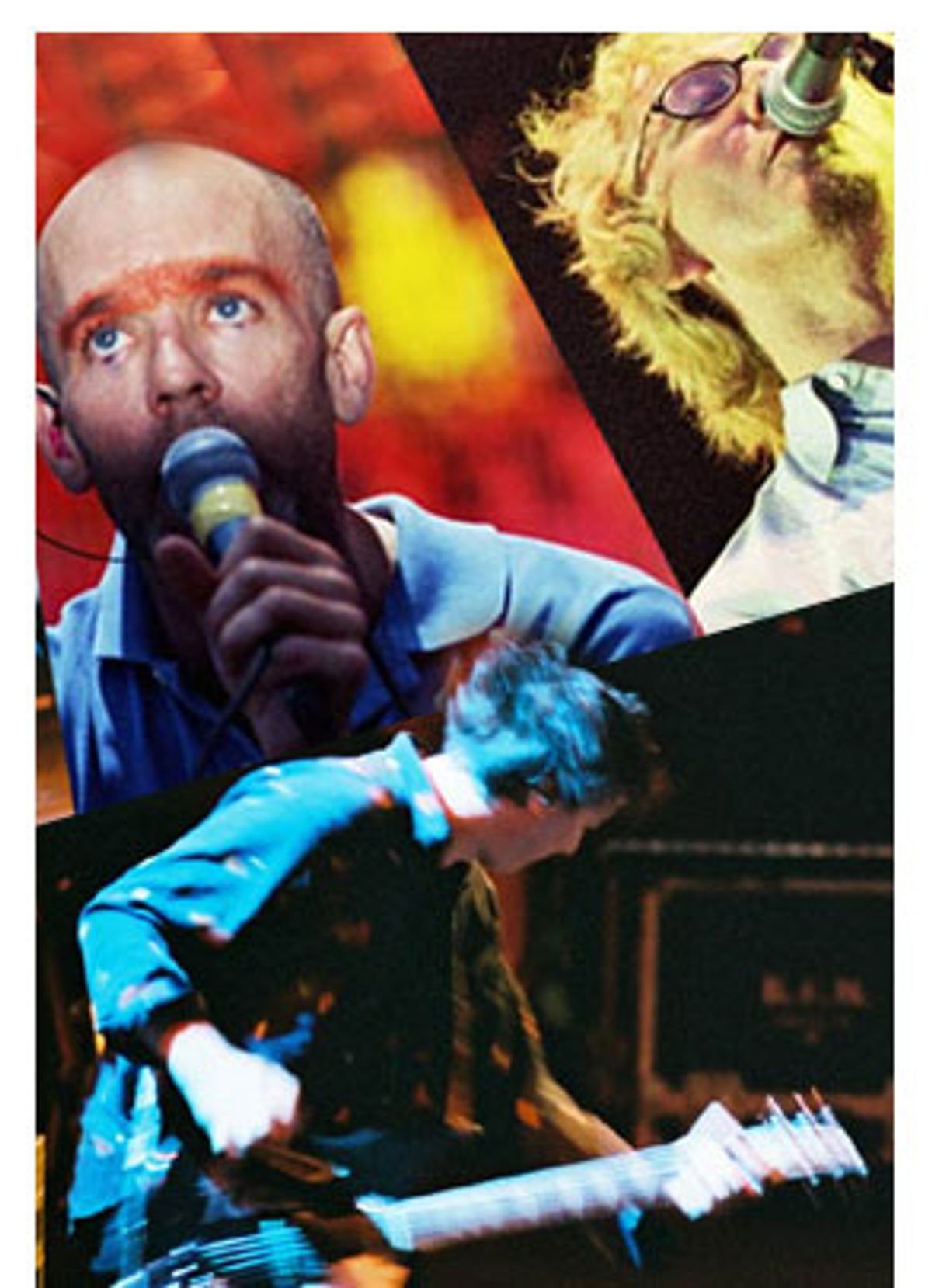

The other thing that made R.E.M. so special was that the group played its peculiar folk-rock variant with the same spastic passion that hardcore punk acts were bringing to bear on their mosh-pit screeds around the same time. In concert during R.E.M.'s early days, Mills seemed ready to catapult off the stage and onto your lap. Stipe, meanwhile, hunched over his microphone behind thick locks of long, curly hair (yes, hair), lurching frenetically from side to side in some sort of weird approximation of a guy having a seizure and a guy contending with ants in his pants.

But a funny thing happened on the way to R.E.M. becoming a thing of beauty and a joy forever for you and your music-obsessed buddies: superstardom. And that's where the group's new career retrospective, "In Time: The Best of R.E.M. 1988-2003," picks up the story. The 18-track collection tracks the arc of mega-success that followed R.E.M.'s departure from IRS (a major label that was run like an indie) and their arrival at Warner Bros. Songs culled from the band's best effort for the label, "Automatic for the People," bookend the disc (the Andy Kaufman tribute "Man on the Moon" and the gorgeous "Nightswimming"), but sandwiched in between are all manner of fits, starts and a certain career-jolting rocket booster.

The latter, of course, is "Losing My Religion," which liner-note scribe Buck regards as a pivotal song in the band's oeuvre. At a time when hip-hop and grunge seemed set to take over the world, R.E.M. reasserted their shaky claim to pop music's throne with a hyperemotive little ditty powered by ... a mandolin. Tarsem Singh's canvas-popping Technicolor video (basically a homoerotic mélange of mythology, Bollywood cinema, and Stipe in seriously prime posing form) didn't hurt matters a bit, either.

Always fan friendly, R.E.M. sweeten the tried-and-true best-of deal with a pair of newish tunes. "Bad Day" upends the manic glee of the earlier "It's the End of the World as We Know It (and I Feel Fine)," with Stipe tapping into the same strain of stream-of-consciousness logorrhea that made the earlier track so infectious as the band rustles up a twangy pop tune. "Animal," meanwhile, finds the group ricocheting gamely between tuneful psychedelia and crusty garage rock.

These new songs are fine, better by far, in fact, than listless and click-tracked ditties such as "Pop Song 89" (from "Green," the group's 1988 Warner's debut) and "What's the Frequency, Kenneth?" (a funny-once joke from 1994's "return-to-rock" contrivance, "Monster"). "Stand," "Everybody Hurts" and the ironically martial "Orange Crush" are here in all their not-so-ragged glory, too, as is "At My Most Beautiful," a sun-kissed souvenir from the group's 1998 hey-at-least-we're-tryin' foray into vaguely ambient terrain, "Up." A couple of soundtrack toss-offs ("All the Right Friends" from "Vanilla Sky" and "The Great Beyond" from "Man on the Moon") round out the collection.

A few choice semi-hits, however, are missing in action. There's no "Shiny Happy People," for instance, and while hardly anyone is likely to complain much about that sin of omission, the disc also leaves out "Near Wild Heaven," a swirling keeper from "Out of Time" that harks back to R.E.M.'s early work in a way that the group would only rarely attempt after making the leap to Warner -- particularly after drummer Berry opted for country-life retirement in 1997.

And that's the thing, of course. Once a rock group's career path marches toward the masses (not to mention toward a scary-huge conglomerate like Warner), it's almost inevitable that at least a measure of what made them unique will get lost in translation. R.E.M. has fared far better than most. Even if they haven't aged as imaginatively as, say, U2, they have managed to negotiate pop music's mainstream without selling their souls. One can only imagine the amount of money they've probably been offered by advertisers for just a snippet of big dumb pop song like "Stand," let alone "It's the End of the World as We Know It (and I Feel Fine)."

For my money, though, that's way too low a standard for a band of R.E.M.'s caliber, a group that basically conjured a scene into existence before they had enough money to make a down payment on a tour bus. So here's hoping that when the band sets up shop in Athens early next year to begin work on its 13th studio album, R.E.M. finally gets around to uncorking that whacked-out two-disc country set you just know they've got in them. That, or maybe a hardcore record. Either would be cool by me.

Shares