I'm hearing gunfire right now, early Monday morning in Baghdad -- loud, echoing bursts of big-daddy automatic weapons, followed by smaller repeating pistol shots trying to keep up. It's been going on since early afternoon and will likely continue through the night as the celebrations over Saddam Hussein's capture ebb and flow across the city. All over Baghdad people who hated the dictator are making the biggest noise they can. This day is huge for them -- emotional, victorious. Everyone hopes it represents a turning point. An Iraqi man I spoke to this evening said, "It's the beginning of a new life tomorrow. Wait for a week and see: With the main terrorist gone, the resistance will stop." I'm not sure that's true, but right now I'd love to think so.

A few hours ago, I was sitting in the sweltering press conference room used by the Coalition Provisional Authority (CPA) here in Baghdad, waiting for Paul Bremer to take the stage and make the announcement. By then, all the people in the room had an idea of what was coming but the room felt oddly subdued as Bremer's appearance was delayed. I had arrived a little late with some other journalists. None of us had really believed the early news on the Web. We'd been through too many "They got Saddam" false alarms. This morning, CPA sent out a mass e-mail announcing a general press conference for this afternoon with the qualifier, "At present, the speakers are unknown." A friend of mine griped that it was typical CPA bureaucratic idiocy to announce a press conference without having decided who would speak. As if anyone would show up to that.

By early afternoon, my housemates and I had decided we'd better get to the press conference -- more and more online news sources were carrying the story that Saddam had been caught. (Here in Baghdad reporters rely quite heavily on Web-based news to find out what's going on in their own neighborhood. It's not at all unusual to learn of, say, a nearby bombing first on the Web, then on the streets.)

Because we arrived a little late, we were almost refused entrance. We had run the gauntlet of security checkpoints to enter the Green Zone, only to get stopped right outside the press-conference room by an overworked, wigged-out soldier in charge of security. We stood with a dozen or so Iraqi journalists, all of us trying to convince the soldier to let us in. The press conference hadn't even started yet. But the soldier kept saying, "No WAY you're getting in. We lost a dog earlier, all right? You are not getting in. We LOST a DOG!" I thought "we lost a dog" must be some weird military parlance. As it turned out, he meant that the bomb-sniffing dog had become exhausted from checking people's bags, and had left to rest. And, even though there were tons of soldiers around, none could check our bags as well as the dog could. A passing general told the soldier to let American reporters in, but without our bags. Later, with the Iraqi press threatening to make an understandable stink about being denied access to what is really their story, they opened the door up to all latecomers.

And so we sat and sweated and jiggled our legs and doodled and nodded to acquaintances and looked for better seats and hoped that Paul Bremer would arrive soon because we just had to hear the news verified before we would allow ourselves to believe it. About 50 percent of the 200 to 300 people in there were press. The rest were soldiers, CPA employees, and handfuls of big beefy contractors with tiny cameras, waiting to witness history in the making. Finally, Bremer entered the room with acting President of the Iraqi Governing Council Adnan Pachachi and chief commander of allied forces in Iraq Gen. Ricardo Sanchez. They stepped onto the low stage at the front of the room and Bremer said, "Ladies and gentlemen" -- dramatic pause -- "We got him."

The room erupted in cheers and shouts. Iraqi reporters in the room began yelling, crying, sobbing. A middle-aged Iraqi man sitting near me wept while he frantically took notes. Other Iraqis called for Saddam's death. A man sitting in the front row wailed with his head in his hands. The press conference paused briefly while the man calmed down. Gen. Sanchez outlined the specifics of the capture: Based on intelligence, the military raided two houses yesterday in the town of Adwar, 10 miles from Saddam's hometown Tikrit. The initial raid and search turned up nothing. They secured the area and continued with a more thorough search. At some point during the search, they discovered what Sanchez referred to as "a spider hole," -- a small opening in the ground leading to a concrete crawl space not much larger than a coffin. Inside was Saddam Hussein.

I try to imagine the few soldiers who initially made the discovery. There's a man down there. Get out. Put your hands up. A scruffy feeble-looking old man with a white beard emerges. He is docile, confused. He has a pistol but does not try to use it. He is Saddam Hussein.

Gen. Sanchez introduced a video of captured Saddam, taken while he was being examined by an army doctor. By now, the whole world has seen this footage over and over. Saddam obediently opens his mouth for inspection. He really does look shattered and utterly impotent. I have no doubt that the footage was carefully chosen to convey just that.

After the press conference, I went to Mansour, a middle-class neighborhood (by Baghdad standards) in the heart of the city. A lot of stores were closed and someone said that many people had gone home to watch television. Other Iraqis were strolling on the street, window shopping or stopping to get a juice in the brightly colored juice joint. When I asked people what they thought about Saddam's capture, they were all unanimous: This is a great day. Had they seen the footage of Saddam? I asked. Yes, they had seen it on TV. He was a coward. He should have killed himself. Instead, he let himself be captured.

I could hear gunfire from rooftops around the neighborhood, but in general people were acting a lot more subdued than I imagined they would. They seemed dazed by it all. Then, too, a lot of people who hate Saddam now hate the Americans almost as much. Saddam's capture feels very much like an American victory. It's a lot for Iraqis to take in right now.

A TV in the juice place showed men dancing and shouting on Karada Street, which isn't far from where I live. I got in the car with the people I was with (two other journalists, two Iraqi friends) and we headed for Karada Street. I've seen mass graves here, met women whose sons were killed by Saddam' regime. Maybe it was selfish, but I wanted to see some celebrating.

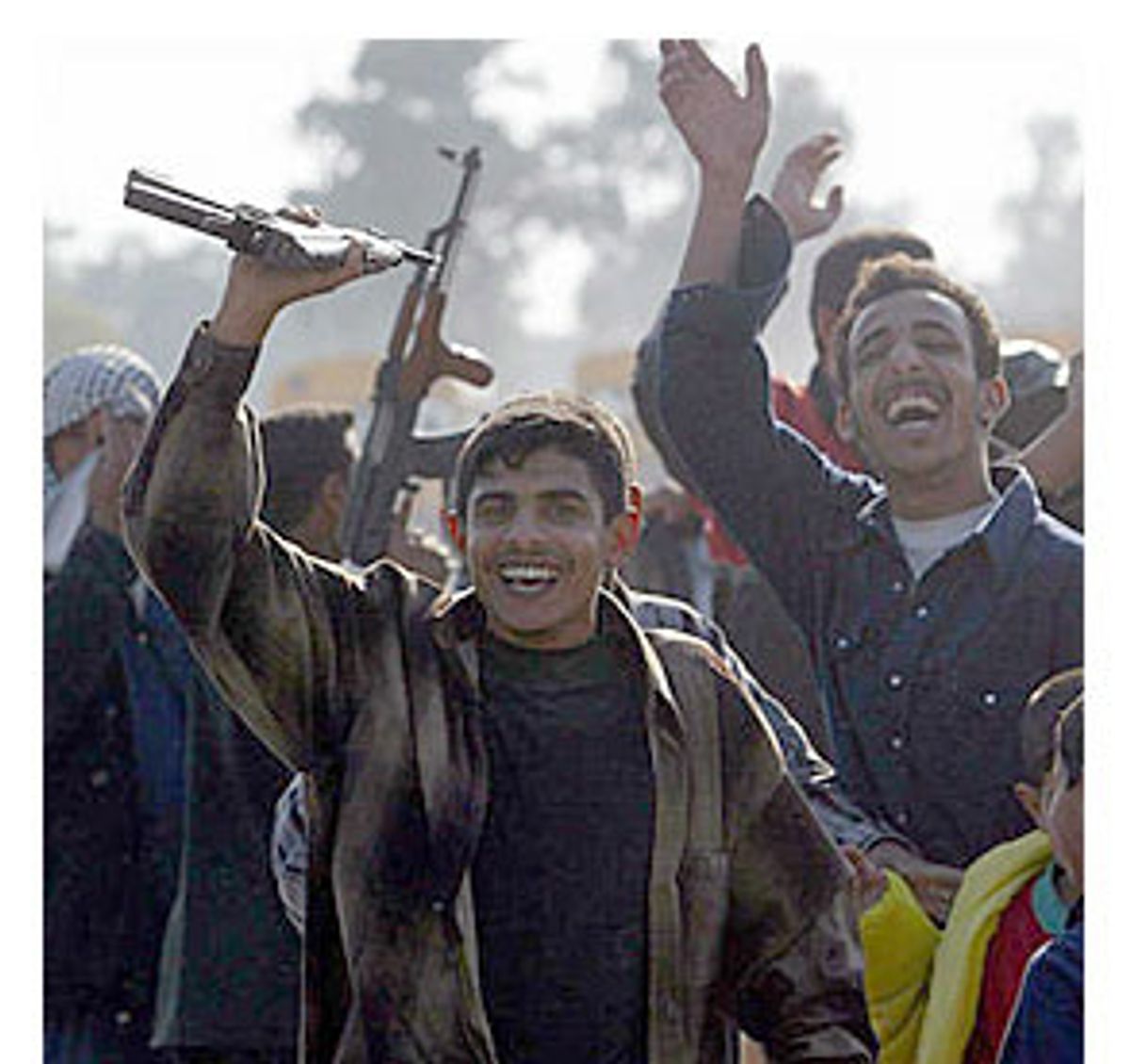

On Karada Street, a bustling thoroughfare of small shops selling everything from vegetables to satellite dishes, we immediately came across a small impromptu parade of people waving large colored flags and shouting joyfully. Two pickup trucks filled with people led the way, honking. Men patted each other on the back and practically hopped along. People approached us as we caught up. "It's a great day!" they shouted. "God has given us victory! He has insulted and humiliated the dictator!" We walked along with the crowd for a little while. Many people watched from the sidewalk without joining the parade. They smiled but, like the people in Mansour, seemed a little blank, too. It hadn't sunk in. Perhaps it never would. Of course, plenty of people in Iraq will mourn Saddam's capture. Not just in the famous "Sunni Triangle" but in Baghdad as well. But I didn't meet any of them on Sunday.

I had, on my digital camera, a video of the footage of Saddam that they had played at the press conference. Men and kids elbowed for a view. It's him, they said. Look at him. They've caught him. Yes, it's him. One happy vendor flung handfuls of wrapped toffees into the air. Children darted through the legs of the adults to get at the candies.

I spoke to an older man in a gray dish-dash named Abdul Hasul. "They must put a rope around his neck and drag him through the streets," he said. A moment later, he changed his mind. "They must put him on trial and broadcast all the court sessions."

People seem to believe that, now, things might finally start getting better. It's hard to know. I can imagine the resistance collapsing with its symbolic leader in American custody. I can imagine the resistance stepping up its attacks in the coming days to prove that Saddam's capture means nothing.

There was some kind of explosion earlier tonight near the Palestine Hotel. Perhaps an RPG attack. Now I'm hearing a man mistakenly shot some gas canisters on a truck when trying to shoot benignly skyward to show his happiness at today's news. The next few days will be very telling in terms of what impact Saddam's capture (and the psychological heft of seeing him defeated and weak) will have on the populace here.

Certainly, it's been a very good day for Iraq. But tomorrow, Iraqis will wake up to another day with spotty power, day-long gas lines, bad water, car jackings, no phones, and not enough jobs. Many of them will continue to feel that being occupied by the Americans isn't all that much better than having lived under a dictator who kept a certain kind of order. I spoke to Ahmed Mulin, a young man with sunken cheeks, right after the sun had set for the day. Up and down Karada Street, shopkeepers lit kerosene lamps so they could continue doing business. The power was down again. Ahmed works for the Iraqi police.

"Maybe this will mean fewer attacks on the police stations," I said. Just this morning a suicide bomb killed at least 17 people at a police station in Khaldiya, 60 miles west of Baghdad. Ahmed believed that it would. "The streets already feel safer," he said.

Then he gestured to the darkened shops on the block. "But look: The electricity is still very bad."

Shares