Music studios here, low on frills and high on voltage, are the nerve centers of Jamaica. Anywhere on the island -- even in Kingston, a car-loving city that scoffs at public domain -- music blares. From car windows, office buildings and beach huts comes the milange of sounds you'd expect (roots reggae, dancehall, hip-hop) and ones that might surprise you (American country music, anything by Celine Dion).

Pulling up to Donovan Bennett's studio in the fairly humble neighborhood called Mona, I smell status: The small street is heavy with big cars, including that music-industry trophy, the Escalade. This colossal entity, says my companion, a local journalist, might belong to Sean Paul, who owns one and is as likely as any other dancehall artist to drop in at Bennett's studio.

Paul, it turns out, isn't in the studio today; neither is customary caller Elephant Man, who's in Los Angeles shooting his latest music video. Bennett, 26, goes by "Vendetta" and is the rising young star behind the revival of the reggae sound that's now a requisite staple of virtually any American pop star -- from Missy Elliott to Beyoncé to No Doubt. He's working today with Vybz Kartel, a 26-year-old lyricist who is dancehall's hottest commodity but who hasn't yet crossed over to the mainstream U.S. market. Kartel, born Adidja Palmer, takes an assertive stance at the mike. He sports the Diesel-esque style -- straight-leg distressed jeans, fitted button-down shirt, platinum pendant -- popular among the dancehall set, and holds his two favorite props: a plump joint of marijuana and a notebook of song lyrics he's about to deliver, rapid-fire and sharply articulated. Kartel dubs his signature style "new millennium dancehall": a hybrid of Jamaican patois and hip-hop slang.

Kartel is big in Jamaica, and Bennett can help make him big in America. But since Bennett is increasingly big in both countries, you wonder if these casual recording sessions will continue much longer. Bennett has lately produced American tracks by the Wu Tang Clan and Alicia Keys, as well as a good chunk of a reggae album currently finding favor in the American market: Elephant Man's "Good 2 Go," which debuted in Billboard's top 100 and featured the MTV-friendly single "Pon Di River."

Bennett, his hair in long, braided cornrows, sits serenely in his chair, like a kid at his PlayStation: intensely involved in his game but still in autopilot mode, and maybe a little bored. He leans forward only to deliver scant commands: "Pronounce it 'Yale,' not 'Yay-all"; or, "ride the riddim better," the dancehall equivalent of "stay on the beat." Bordering on shy, Bennett is the epitome of a behind-the-scenes man.

Bennett plays the "riddim," the unique beat that the song will be centered on. This riddim is called "Chrome," a catchy confection of drums and steady electronic accents that is already a success: Big-name artists have recorded songs over it, and this week it backed the No. 1 song on Jamaican reggae charts ("In Her Heart" by Capleton, a Rastafarian known for his fiery delivery). Though Bennett didn't make "Chrome," the man who did -- a middling artist called Alozade -- asked Bennett to produce this, with Kartel on vocals.

For his 2003 debut album, "Up 2 Di Time," Kartel teamed up with Bennett; before that he made his name as a lyricist, ghost-writing for other artists. The track he delivers today is a meticulously rhymed, uproarious ditty in which he and Alozade are jailbirds. In real life, both have indeed served prison time; Kartel's December arrest on weapons and assault charges was reggae's talk of the town for weeks.

"It's just another Biggie and Tupac thing," he says of his arrest, which was prompted by an altercation with a veteran dancehall artist he'd been feuding with. I remind Kartel that the "thing" of which he speaks didn't have a particularly happy ending: Neither rapper is alive today.

"Good point," he says, then laughs.

Kartel laughs often, and heartily. Instead of a hardcore gangster track à la Tupac or Biggie, Kartel's track is comedy, a witty mini-narrative -- which he now delivers into the mike -- about day-to-day nuisances of prison life: Oh, if only that prison slop were red snapper and rice!

"Whatever people are rhyming about, I try to do differently, to put a twist on it," Kartel had explained earlier. "Like, for instance, everyone is talking about the pussy -- so I'll talk about the breast. Seen?"

Kartel, of course, also talks about pussy: One of dancehall's most beloved subjects, female genitalia are never overlooked. Dancehall can make Spike TV look downright girlish. It is, with scant exception, an all-male genre that spawns both virile political anthems, some of which have been censored off Jamaican airwaves, and a trailer load of sexual swagger, known in patois as "slackness." The Rabelaisian nature of such swagger -- a carnivalesque celebration of all things corporal -- is too over-the-top to offend. Handled artfully, explicit fare like this is dancehall's greatest selling point: Everyone relishes an uproarious-yet-salacious bedroom story. Handled clumsily, it gives dancehall a bad name. Dancehall's acute veneration of heterosexual sex tends to produce homophobia, the genre's longtime bête noire. For over a decade, consummate dancehall artists have penned anti-gay lyrics that effectively wrote them off American airwaves.

Now that American ears are listening, artists temper lyrics. Ever so slightly, though: For American ears, unschooled in Jamaican patois, lyrics are beside the point, anyway. Dancehall crosses over via simple English hooks (Sean Paul's: "Get Busy," or "Gimme the Light") and especially via the product that Bennett manufactures: riddims, the vital, essential currency that fuels the new reggae sound, and transcends language altogether.

Growing up in Westmoreland, a rural parish of Jamaica, Bennett relocated to Miami for college, graduating from the American Technical Institute. "I knew it'd be music, what I'd do with my life, but I didn't know it would be producing," he says. Moving from Miami back to Jamaica, he settled in Kingston, established the "Vendetta" sound system, a roving DJ business, and casually began doing what Jamaican DJs do: make riddims. Every DJ has a beat, though, and many have good ones; only a select few have enough savvy to accrue the dozen or so vocalists who record over them.

"That's kinda tricky, that part," is Bennett's assessment. It's an understatement. For big-name Jamaican producers -- like Sly and Robbie, who lately produced pop group No Doubt's Grammy-winning reggae single "Underneath It All," or Jeremy Harding, who works with Sean Paul -- getting dancehall stars to make songs for their new riddim can be as easy as a direct phone call and a handshake. But for unknown beat makers, the process involves hustling, haggling and, when all else fails, imploring. There are no rules and no fixed rates. An artist might offer vocals to a riddim for free -- because he likes it that much, or because he needs it to boost his career. He might get a tip of several hundred dollars, or, says Bennett, a couple thousand. Forget American music-industry notions about singles that promote albums, or studio vs. tour time. Whether a new album is on the way or far away, whether he's touring or in his yard, any dancehall artist who's invested in his Jamaican fan base -- from Sean Paul on down -- stays on top of the riddim trade, regularly recording singles over the new, best ones. A good share of these recordings are befuddling entities to an American record exec: floating singles, done for a puny fee, never to appear on any album.

Sound system gigs gave Bennett enough music-industry contacts to collect vocalists for his early riddims. Artists began approaching him, turning his Don Corleon Records into a hot commodity.

The best of Bennett's riddims, created in the last couple of years, are musical compositions in their own right. "Egyptian" has a delightfully quirky, kitschy melody line that would make an apt theme song for a video game about ancient Cairo ("Speed Through the Pyramids"?). "Good to Go," Bennett's favorite, is a simple guitar lick that goes a long way, a pared-down riddim that left much room for interpretation and thus inspired several distinct-sounding hits.

Bennett smirks when I ask him how he decides which artists to put on his riddims. Many, of course, are obvious picks: Sean Paul, Elephant Man or, lately, Vybz Kartel.

"Yes, Sean is the same about my riddims now as he used to be -- if he likes it, he'll come and record," Bennett says with a shrug. But dancehall is a notoriously here-today-gone-tomorrow industry -- how does he sift through all the up-and-comers? "I can't say yes to everyone, but I try to listen when I can. I gave Kartel a try, and it worked out well for both of us, right?"

Hours later, Bennett, Kartel and those who've lingered pile into Bennett's control room to sample the fruits of their labor: the final addition to the "Chrome" riddim, unofficially dubbed "Prison Life." Bennett plays the track; his entourage howls with delight; Kartel, eyes red from ganja, spirits high from Hennessy, blissfully renders judgment: "Dat a bomba-claat tune, yeah!" -- patois for, roughly, "That's one hell of a song, indeed!"

Because its riddim is popular -- and so is Kartel himself -- this new song will soon be on every club DJ's playlist. It'll then make it to radio and, perhaps, onto an album: maybe Kartel's, or some compilation CD. But for the moment, the song's here-and-now is what matters: It'll make Kartel and the riddim yet more popular -- and popularity means more work, and thus more paychecks for artist and producer both.

On the way out of Bennett's studio, I meet DJ Liquid and Coolface, producers who work with Bennett. Each has a new riddim on the market. DJ Liquid's "French Vanilla" is already popular, while Coolface's "Cool Fusion" riddim -- his first -- is still in development: He's recruited Kartel and several others to supply vocals on it, but is eager for names that'll increase its spins on radio and in clubs. Coolface stops my ride, a producer for Jamaican music television, and asks her to personally deliver "Cool Fusion" to Buju Banton, a reggae crowd pleaser who hasn't yet agreed to make a song for it. A track by Banton is sure to give the riddim a boost. She takes the CD; we exit Don Corleon Records with beat in hand, middlemen in the inexhaustible riddim trade.

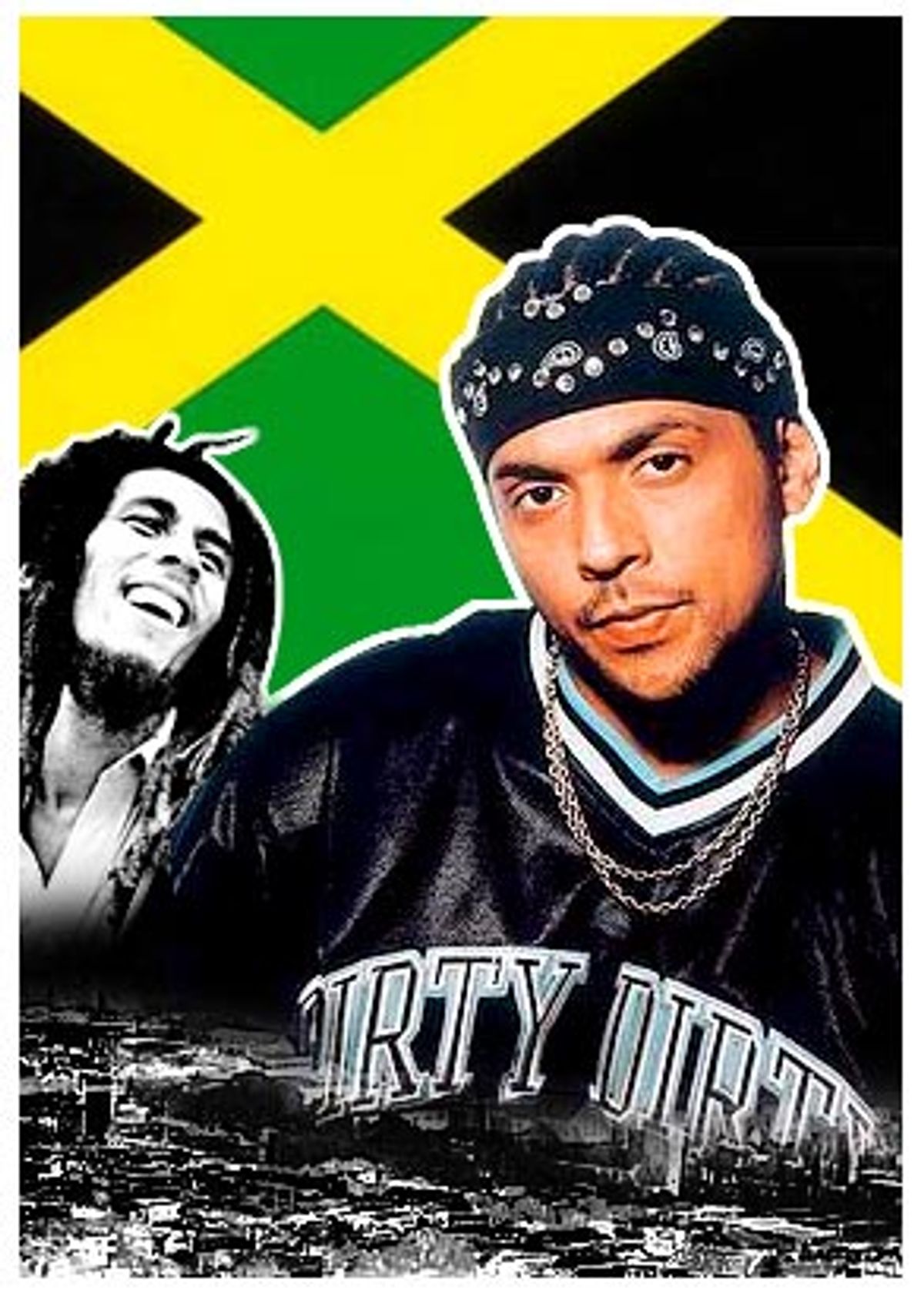

Bob Marley, of course, is the supreme figurehead of roots reggae, which is what you probably think of when I say "reggae": music reflexively associated with beach resorts and rum punch, live bands and dreadlocked singers who praise Jah. Bennett, on the other hand, deals in the other kind of reggae, the beat-based electronic music, known as dancehall, that's now the prime currency of the contemporary Jamaican music industry and a major influence on American pop.

If the past 30 years of reggae have a historical arc, then Marley and Bennett -- hardly of the same stature but very much in the same field of work -- might well frame it.

Dancehall was born before Bob: at Jamaican parties during the late '50s, where men with modish monikers -- Count Matchukie, U-Roy, King Stitt -- were garrulous hosts. Inspired by American radio DJs, they chatted ceaselessly over the music, serving up smooth talk like this, courtesy of King Stitt: "No matter what the people say/ These sounds lead the way/ It's the order of the day from your boss deejay/ I King Stitt."

They're reminiscent of American hip-hop lyrics -- and well they should be: "Toasting," as chatting over music was soon called, became a Jamaican art form that was transported to the Bronx in the early '70s by immigrants like Clive Campbell, better known as DJ Kool Herc -- forefather of a "new" style of American music in which men rhymed over prerecorded music and dubbed themselves "rappers."

In America, rappers became stars of the billion-dollar industry that hijacked pop culture. Jamaica's golden-tongued talkers -- eventually called "deejays," still the name for dancehall artists like Sean Paul -- weren't as lucky. In the late '60s, tech-savvy producers found a way to separate a track's vocals from its instrumentals, and invited deejays to put their party routine on wax. A popular genre was born; it was amazingly cost-effective; it was quickly eclipsed by another genre that exploded alongside it during the early '70s, music that's still the ambassador of all things Jamaican: reggae. Bob Marley and Jimmy Cliff had melodies, looks and lyrics that made them global superstars. Deejays like U-Roy or Dennis Alcapone had, in foreign eyes, none of the above -- not pretty faces, inspirational melodies, or even intelligible lyrics (unlike reggae singers, dancehall deejays doused their speech in thick patois). Reggae was international music; dancehall was local stuff.

A mouthpiece for the Caribbean underclass, dancehall was derided, for many years, by the Jamaican upper crust and some of its public officials, all but ignored by foreign critics who dismissed it as a paltry, lowbrow derivative of "the real thing" (code phrase for "Marley"). In 1994, Jamaican poet Mutaburuka dubbed dancehall "the worst thing that ever happened to Jamaican culture."

Of late, however, the tide has turned. It began in late 2002, with a musical hook about an herbal substance kind enough to transcend cultural barriers. "Just gimme the light," sang a then-underground dancehall artist named Sean Paul. Never mind that most Americans aren't fluent in Jamaican patois, the idiom of dancehall reggae. The sheer energy of Paul's "Gimme the Light" -- and its glossy video, which soon earned rotation on MTV -- made words beside the point. It launched a string of Sean Paul hits and a $7 million joint venture between Paul's label, VP Records, and Atlantic Records -- a deal Atlantic co-president Craig Kallman called "a watershed moment in the history of dancehall." Red, gold and green became the color scheme of the moment, adorning Puma's Jamaica-themed sneaker line and last summer's MTV Video Music Awards -- where Sean Paul, nominated as best new artist, faced a sea of Jamaican flags. Paul, nominated for three Grammys, won one for "Dutty Rock," the first undiluted dancehall reggae album to ever go platinum (then, double platinum). In 20 years of reggae Grammys, Paul is only the fourth dancehall artist to bring it -- and now an irrefutable point -- home: The music that was reggae's bastard child had become its favored son.

But if Sean Paul is the obvious poster boy for dancehall's success, it's the producers, like Bennett, who are the industry staples. These low-profile men have long been making high-profile beats that define the genre.

Instead of building a new beat for every new song, dancehall features multiple artists recording over a single beat, the riddim. Here's the process, in a nutshell: Bennett makes a riddim; he invites 20 or so artists to devise lyrics and melodies for it; reggae radio gives about half of these songs airplay at a given time. It's musical recycling, akin to a literary challenge in which 20 authors are given the same plotline and told to produce individual short stories. If you don't believe that one beat can go a long way, take a close listen to two dancehall tracks that hit the Billboard jackpot last year: Sean Paul's No. 1 smash "Get Busy" is a bouncy, hip-hop-styled dance track, and Wayne Wonder's "No Letting Go" is a dulcet love song; both are recorded over an entity known as the "Diwali" riddim. Or consider R. Kelly's dancehall-flavored recent hit "Snake": A slew of reggae artists co-opted its beat -- soon rechristened the "Snake" riddim -- and recorded songs over it that scarcely evoke the original track. Dancehall riddims generally earn names before individual songs do -- a fact that cuts to the heart of the genre's musical formula.

"A producer can't do it all; the artist plays a big role," insists Bennett, but he does admit that riddims often trump all: "If my riddim is hot, and it's getting a big buzz, every artist will want to have a song on it." To understand dancehall reggae's current wave of crossover is to take a tour of the riddim trade, to glimpse how Jamaican music makers -- short on pricey resources that the American music industry takes for granted -- crafted an alternative musical system that wrings a lot from a little.

Bennett is in the midst of looking for a part-time home in Miami. He's lately been doing some work for Def Jam, and an American base would ease the commute to New York. "It's business," he shrugs. Little seems to excite Bennett; music is his 9-to-5. Only the subject of VP Records -- the largest U.S. distributor of Jamaican music -- gets him riled up. "They're crooks," he says of VP, claiming that unlike Greensleeves, whom he works exclusively for, VP asked him to sign away publishing rights to all songs on his riddims. "We need local, Jamaican distribution for music," says Bennett, now animated. "But obviously that'll take big money, and we don't have it here."

Not yet, anyway. And according to those critical of dancehall production, big money would mean big improvements. "It's lazy work, the riddim system," says Stephen "Lenky" Marsden, one of the most successful producers in dancehall. "I don't think it's creative, this business of everyone on one beat. It only persists because of our economy -- because we don't have any money."

Marsden is a keyboard player who, like a host of Jamaican musicians -- notably Sly Dunbar and Robbie Shakespeare, who once backed Bob Marley and Peter Tosh -- suddenly confronted an electronic-based riddim method that made instruments practically passi. Instead of beating the system, Marsden, and the others, joined it. In 1998, he created the "Diwali" riddim, which is basically a series of hand claps. It sounded like nothing dancehall had ever heard, so initially only two minor artists agreed to voice songs over it. But "Diwali" became the most successful riddim in recent history, backing three Billboard hits last year, including Sean Paul's first No. 1.

Marsden, meanwhile, keeps reminding me that he -- unlike Bennett -- is first and foremost a musician; he's fixated on the fact that in riddim-run dancehall, "The music has been lost." He'd like dancehall to start promoting well-rounded, artistic producers who make albums, not just riddims. "Like a Dr. Dre, he knows how to make a complete product." I'm startled to hear Marsden demand the demise of the riddim method, the meat and potatoes of dancehall.

"Hear this: You can go out and make a riddim right now, and get some artists to sing anything over it -- lyrics don't even matter, anyway. There are so many stupid bubblegum Jamaican songs out there," he says. "And I'll bet you can get your riddim on the radio and get a deal. Go ahead -- do it and get back to me."

As pure as Marsden's sentiments are, they strike me as a tad too flippant. Before I fly out of Jamaica, I arrive at Early Mondays, one of countless outdoor fêtes that occur nightly in Kingston's ghettos. To a jaded American, such parties are a shock to the system: outdoor affairs -- free ones -- that consist of colossal speakers on the road and masses of dancing people wearing outfits that make Daisy Dukes seem prudish. There are no bouncers, I.D. checks, or lines at the door. In America, a party scene like this would be sucked up by the corporate structure faster than you can say "sponsored by Absolut."

As it happens, reggae celebrities regularly attend Hot Mondays, and they're here tonight. No one pesters them. Elephant Man relaxes with his crew near the concession stand, and Ghost -- think of him as a Jamaican El DeBarge -- stands by the wall. Elephant Man's look tonight is minimalist -- as compared to his usual attire, which generally involves giant sombreros or full football gear. His hair, dyed bright yellow, is braided and worn in pigtails; his T-shirt -- Phat Farm or Sean John, or some other hip-hop brand euphemistically labeled "urban" -- is adorned with an enormous platinum pendant of indeterminate mass. Nicknamed the "energy god," Elephant Man is known for his self-described "crazy hype" live act -- not a concert but an exuberant reggae revue: He dances! He chats! He climbs rafters! He sings "We Are the World," utterly off key!

"The hook, the hook is the key," Elephant Man says when asked of his crossover success, dropping the "h" so it sounds like "ook." "You've got to keep the Jamaican flavor there but make it so that Americans can understand it. Like" -- he launches joyously into the chorus of his first crossover hit, "Pon di River" -- "'I've seen 'nuff dance before, but I've never seen a dance like this!' You see: Everyone can sing along to that!"

Fresh off the plane from Los Angeles, Elephant Man will return there later this week to perform at the annual Bob Marley Day Festival. Between flights, new riddims await his vocals. They always do. A producer's dream, Elephant Man churns out a song -- or three or four -- in the time in takes another artist to pen a line.

I get an update on Coolface's "Cool Fusion" riddim: Buju Banton likes it but won't be gracing it with a track. All is still well for "Cool Fusion," though; it's getting radio spins and is featured on the new album by Sizzla, a devout Rastafarian who, along with Vybz Kartel, is contemporary dancehall's underground favorite. Sizzla has style and subject matter that run the gamut from spiritual hymns about Ethiopia to tracks that tackle less sacred matters, like how to "pump up" a woman's "pum pum." The selector spins Sizzla's latest tune: "I was born in a system that doesn't give a fuck about you nor me, " he chants. The crowd roars.

Bennett produced this track, and Sizzla's entire new album. I scan the crowd for Bennett, but unsurprisingly, he's not here. Not in the flesh, anyway; Bennett's handiwork -- one riddim after the next -- is ubiquitous. The Kartel track I'd witnessed him producing will probably debut -- from speakers like these -- sometime next week. Before (and if) they make it to radio, new riddims and songs are introduced here, at Kingston dances.

As I consider Marsden's insistence that the riddim method is so cheap and uncreative that even I can succeed at it, the selector switches to his "Diwali" riddim. One beat, so many songs, all of them distinctive: Sean Paul chats rapidly over the beat; Elephant Man sings a nursery rhyme; Buju Banton delivers an ecstatic prayer. This is the riddim method's glory: A simple series of claps, a crew of innovative ears -- and voilà! A crate of rapturous tunes. It strikes me that American artists, paying producers for a new beat that's good enough to sell records, can essentially make hits from cash. But the riddim method, in which few artists get a beat all to themselves, has an egalitarian spirit. Its practitioners are presented with identical raw material (a riddim) and the same mission: transform something ubiquitous into something unique.

The crowd begins clapping furiously. They're performing the dance associated with the "Diwali," a dance American teens learned last summer as they lapped up Sean Paul and Wayne Wonder's "Diwali" songs. Tonight, the clapping strikes me as applause -- for Marsden's riddim, which helped dancehall cross over last year, or maybe for the riddim method itself, which, in the right hands, can produce so much from so little. The clapping seems loud enough to reach Bennett's studio in Mona, where he's surely busy with a new riddim: more merchandise for the Jamaican music trade, yet another beat bearing the voice of Jamaica and, soon, carrying it overseas and to our airwaves.

Shares