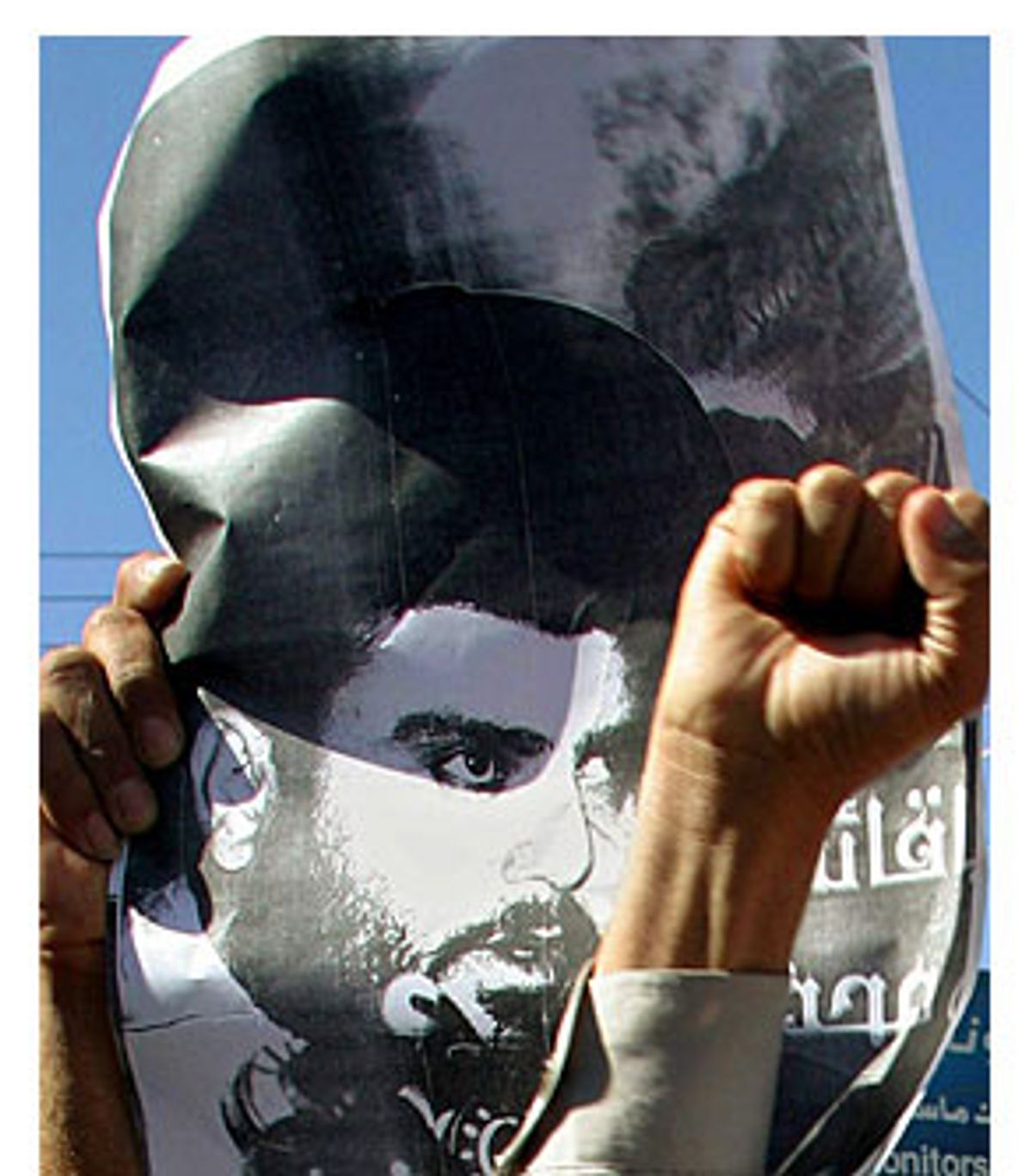

Last week, before followers of Muqtada al-Sadr began actively fighting coalition forces, before four Americans working for a private security company were killed and mutilated in Fallujah, I left -- or perhaps I should say fled -- Iraq. In the week or so preceding my departure, I felt the country undergo an essential, albeit subtle, shift. The anger previously focused on soldiers and members of the Coalition Provisional Authority seemed to morph, almost daily, into an indiscriminate ire toward Westerners in general. Almost overnight, I stopped feeling safe.

Many of my biggest concerns were wrapped up in the fact that I had been in the country so long. I (and the house I shared with other freelance journalists) had become well known. Some seasoned war correspondents -- friends who had actually lived in the house last fall -- warned us that they felt the house might be marked as an easy "soft target." Journalists and contractors were moving en masse out of small, lightly protected hotels (such as the Mount Lebanon, which was bombed a few weeks ago) into hotels that lay within heavily guarded and restricted compounds. With fewer easily available Western targets, my friends believed that the house might be ripe for an attack.

Up until a month ago, my housemates and I joked about Western journalists and civilians who were obsessed with security. We made fun of our friends who worked for TV networks and had to get permission from New York just to come to our house for dinner. When they did come, they traveled in armored cars with armed British former special ops soldiers. For six months we had gone all over Baghdad and Iraq, driving in a regular old Iraqi car with an unarmed translator and driver. Going shopping, walking on busy streets, wandering into crowds. There was always some risk, but it was small. The soldiers were the real targets. Iraqis might hate the occupation, but they didn't hate Americans per se.

Then, seemingly overnight, everything felt different. It began with the Mount Lebanon bombing. Though many journalists I talked to also sensed the city's mood shift, it was hard to figure out exactly why that particular attack made us feel so different. We had been to blown-up hotels before; it happens every few months. But it wasn't the bombing, it was how Iraqis were talking to us. Iraqis are fed up with the occupation. They're fed up with what they consider to be a year's worth of false promises. They're fed up and the situation is getting very ugly.

A driver we worked with told us that our house had been targeted and we needed to "take a break" from Iraq. One of my housemates (who had been in Iraq as long as I had) heard that there was a rumor circulating that he was actually CIA. It was time to leave.

In the few days that passed between when I made the choice to leave and actually got the hell out, I became even more aware of the threat in the city. I wore a hijab pulled close around my face when I drove through town. Now all female journalists I know wear a hijab and even a full-on abaya when they leave their hotel. And not just female journalists -- a few guys I know who are unfortunate enough to have blond hair have taken to covering it with a head scarf when driving through the city. On the one hand, we joke about it -- "Shit, you make a good-looking old Iraqi woman" -- but it's deadly serious.

Now in Baghdad, in addition to the fortified "Green Zone" occupied by the Coalition Provisional Authority, other heavily guarded compounds have sprung up to encircle the hotels most populated by Westerners. During the war, almost every Western journalist who chose to stay and tough out the conflict took refuge in the large Sheraton and Palestine hotels that sit, almost lobby to lobby, a block away from the Tigris River, opposite the river from the Green Zone. Following the fall of Baghdad, American soldiers parked tanks in front of the hotels and (somewhat informally) secured the grounds. Still, it was possible to drive a car filled with luggage into the parking lot (as I did the day I first arrived in Baghdad last May) and move freely around the streets flanking the hotels.

Over the course of the last year, however, the security perimeter for those two hotels has slowly but surely expanded to encompass an entire neighborhood. Roadblocks, cement barriers, concertina wire, and legions of private guards keep a tight rein on anyone entering the area. A big chunk of Abu Nawas Street, the wide boulevard that parallels that side of the Tigris, is completely blocked to traffic. News organizations and foreign companies have rented many of the larger homes inside that secured zone and each employs its own security guards. Men with Kalashnikovs roam the empty street or park themselves at the front gates of the sandbag-wrapped houses. If you look up, you're likely to see more men with guns pacing the flat roofs and keeping watch on passersby. The New York Times was one of the first organizations to take up residence there. Last spring, before Westerners of all kinds were being targeted, they rehabilitated a large home and painted the outside bright pink and purple. I used to joke that it looked like an MTV "Real World" Baghdad house. Not long ago, I noticed that the house had been repainted to a dull white-gray.

The isolation of Westerners only feeds the danger, in a kind of vicious circle. With journalists and civilians in Baghdad now living the same way soldiers and CPA staffers do, it's no wonder the Iraqis differentiate among those groups less than they used to.

After our friends expressed their concerns about our house being vulnerable -- but before we received the more specific threats -- my housemates and I decided to consult with some of the security companies working in Baghdad to get an assessment of our danger level. The house we lived in was not in a cordoned-off area but rather a quiet residential neighborhood. Our idea was to be as low-key as possible. We had a guard at all times but he usually stayed inside the wall that fronted our house. Early last fall, when we rented the house, low-key was the best way to go. In fact, part of the impetus for getting the house in the first place was that hotels (even those with security) seemed the greatest risk to Westerners.

Private security companies can be found all over Iraq right now. Most of them consist of a cadre of well-trained Westerners -- usually some version of former special forces guys from the U.S., Australia or South America -- supplemented by Iraqi guards. The biggest companies, like Custer Battles (whose unfortunate moniker actually derives from its two founders' last names) and Blackwater (the employer of the four men killed in Fallujah), are hired almost exclusively to act as armed security support for the military and Coalition Provisional Authority. They provide escorts for contractors and create secure areas (like the Green Zone) in which different arms of the coalition live and work. Some of the contracts are massive. Custer Battles essentially runs the airport.

A number of security companies have carved out multiblock areas in the wealthy Mansour neighborhood of Baghdad. I drove to Mansour with one of my housemates to talk to some people at Erinys Security, a large firm (with ties to Pentagon favorite Ahmed Chalabi) working throughout Iraq. When my housemate and I made an appointment over the phone, the Erinys guy had given us rough instructions to their compound. He told us to drive to a street behind the wrecked communications building and then look for a lot of men in blue shirts. We followed his instructions and, sure enough, came across a gaggle of beefy Iraqis wearing blue Oxford-type shirts and holding Kalashnikovs and mini-machine guns. My translator, Amjad, who was with us, explained we had an appointment. The men directed us to pull up to a barrier that marked the beginning of a blocked-off fragment of the neighborhood. We milled around outside our car while one of the guards crossed the barrier and ducked into a house just beyond to announce us. The dozen or so guards around us seemed bored. Some stood with their rifles hanging in front of them, supported by the kind of neck straps I associate with guitars. They chain-smoked cigarettes and laughed in surprise at my housemate's decent Iraqi Arabic.

After a few minutes, a very scrawny American guy came out of the nearby house and walked over to greet us. He was casually, even sloppily, dressed with longish lank hair and teeth that reminded me of late-season corn on the cob. There was something decidedly creepy about him. Certainly, he didn't inspire any strong feelings of security. After a slightly confused exchange, it became clear that we weren't even at the Erinys headquarters. This was a different security company with different blue shirts and a separate compound. The man offered to help us, but we told him we had another appointment and had to move on. We asked if he knew where the Erinys compound was -- we knew it was close. He shrugged and said that there were lots of security compounds in the area and he wasn't sure which was which.

Though Mansour lies in the heart of Baghdad, it feels more like a suburb, or like parts of Los Angeles. Imagine driving through a suburban town in which, at any given moment, you're likely to come across a roadblock manned by up to a dozen heavily armed men, marking the entrance to a small compound. If you live inside, you will have to show an I.D. and have your car checked for explosives whenever you enter the compound. Though right now Mansour seems to have the highest concentration of these compounds, they are quickly springing up all over Baghdad. For Westerners, it's increasingly unrealistic to live outside the bounds of these mini-Green Zones. Iraqis whose houses get inadvertently annexed by these zones choose to rent their homes to whichever company has taken over. Others choose to stay and accept the trade-off: hassle for high security.

We did eventually find Erinys that day. As it turns out, they are a very large and high-tech operation with a contract to guard oil pipelines throughout the country. For that, they employ more than 10,000 Iraqi guards. Advising a handful of journalists on the safety of their living situation wasn't exactly the company's regular gig, but they were incredibly amenable to helping us and, the following morning, a consultant came by our house to advise us. He recommended that we increase the number of guards and line the inside of the wall in front of the house with sandbags. In general, he felt that we could make the house safe enough to warrant staying.

Then came the change in the atmosphere, and the threats.

The viciousness of the attacks on the four Blackwater employees in Fallujah illustrated, in an incredibly depressing way, the shift I felt on the streets of Baghdad. An explosive anger just below the surface of daily life. Of course not all Iraqis want to kill Americans. But the violent minority could easily tip the country toward yet another out-and-out war with the coalition. As I write this, coalition forces are fighting Saddam loyalists in Fallujah and nearby Ramadi and followers of Muqtada al-Sadr in a number of cities throughout the middle and south of Iraq. At least 18 U.S. Marines have been killed over the last three days, with 12 more reported slain today in Ramadi; at least 130 Iraqis have been killed. The next few days on those fronts will be very telling.

On the surface, the clashes in Fallujah and Ramadi aren't related to the Shiite actions: The Saddam loyalists of Fallujah don't historically have much in common with Shiite hard-liners, who were persecuted under Saddam's rule. In that sense, the timing couldn't be worse. The coalition is now fighting battles on several different fronts simultaneously. Their hard clamp-down may quell some of the violence. But I think it's more likely that it will severely aggravate it. Al-Sadr's followers, including his well-armed Mahdi militia, will fight fiercely to block his arrest. If enough of them get gunned down, non-Sadrists might join the fray. Though al-Sadr doesn't command nearly the same respect as the more moderate Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani, his outspoken vilification of the United States may position him as a "mouse that roared" figure and enable him to sidestep into Iraq's severe leadership vacuum.

But even before the current crisis, something may have happened to ordinary Iraqis that cannot be reversed. When I sensed the country's mood change before I left Iraq, I wasn't hanging out with Saddam loyalists or members of al-Sadr's militia. I was in Baghdad talking to average people.

To be fair, I think part of what changed in the last few weeks was me. After seven months in Baghdad, with low-level stress all the time and high-level stress a few times a day, the heightened danger and the disappointment of seeing the country fall apart was too much.

Last May I felt some sense of optimism about the future of Iraq. But since then I've witnessed the nation's slow decline toward the present chaos. The occupation, perhaps doomed from the start, is proving to be a failure. I've heard from plenty of CPA employees (off the record, of course) that the governmental situation is a mess. Reinventing an Arab-nationalist socialist dictatorship as an American democracy is too great a task. The Bush administration's fantasy about how it was going to transform postwar Iraq reminds me of a "Star Trek" episode in which a confident multicultural, quasi-military group beams down to a planet where people are following the wrong leader. The Enterprise crew quickly implants American-style democracy and, by episode's end, are light-speeding toward another galaxy, safe in the knowledge that the changes they've wrought are good and right and will endure. It doesn't work that way in real life.

Though I was against the war, when I first got to Iraq I couldn't help feeling (especially after a trip to the mass graves) that getting rid of Saddam would improve the lives of Iraqis. Now I'm no longer sure.

In my final weeks in Baghdad, I started feeling constantly on edge. The gunfire that I had become so accustomed to hearing as part of Baghdad's background noise was suddenly sending my stomach into my throat. Getting stuck in traffic no longer felt like a petty annoyance; it felt like a trap. When I visited a university to interview some students, I encountered a much more hostile reception than I had at the same university last fall. Pretty much all the American journalists I knew began saying they were Canadian (much to the chagrin of the actual Canadian journalists). Certain news reporters started "covering" stories about events in Iraq by recycling what they read on the Web and watching CNN instead of actually going to the scene.

Then, too, I became very worried about the safety of my driver, Thamer, and my translator, Amjad. In the last month, Iraqis working for American news outlets such as Time magazine, Voice of America, and the Washington Post have been threatened and killed. (Both Time and the Washington Post moved out of their relatively low-key houses and into hotels within security compounds.) While neither Amjad nor Thamer expressed any fear to me, the idea that they might be targeted truly terrified me. Neither had exactly advertised the fact that he worked with an American but, after seven months, word gets round.

The same experienced war correspondents who warned of the danger to our house told me that they believe the situation in Iraq right now is much more hazardous than it was during the actual invasion of the country (and they were both in Baghdad for it). It's a question of the unknown. The increasingly large X factor of being in the wrong place at the wrong time.

On the day before I left, I was driving back to my house with Amjad, Thamer and another journalist. I was famished and asked Thamer to stop at my favorite roadside kebab stand to get some sandwiches. Amjad, the other journalist and I stayed in the car while Thamer jogged across the street (with its raised dirt median) to the kebab stand. I slouched in the back seat and watched a man sweeping the sidewalk nearby. Across the street, two men in jackets and ties sat at a small plastic table, eating a mound of food from the kebab place and laughing at some shared joke. Down the block, a woman in an abaya looked over the pile of lettuce at the vegetable stand. Cars passed us -- junky orange-and-white paneled cabs, new-looking Mercedes, minivans filled like buses, a black car with no license plate.

Across the street, Thamer stood waiting for the kebabs with some other Iraqis. Amjad and the other journalist played games on their phones. The black car without a license plate passed us going in the other direction. Then, a minute later, it passed us again. I told Amjad to move into the driver's seat and take off. We sped away, making a bunch of fast turns to be certain we weren't followed. Minutes later we were at the house and Amjad went back to pick up a confused but understanding Thamer.

It's possible that the driver of the black car (which contained at least one passenger) was lost or looking for an address or cruising for prostitutes. That he had no idea some Westerners were hanging out in a parked car, waiting for some sandwiches. It's possible I was experiencing a case of short-timer's paranoia. I've seen too many bad cop movies where the old sarge who's retirin' in a week to finally do that fishin' he's been talking about for so long gets blown up in the third scene. There's no way to know. But right now in Iraq, the assumption of danger is the safest bet. It is not safe.

Shares