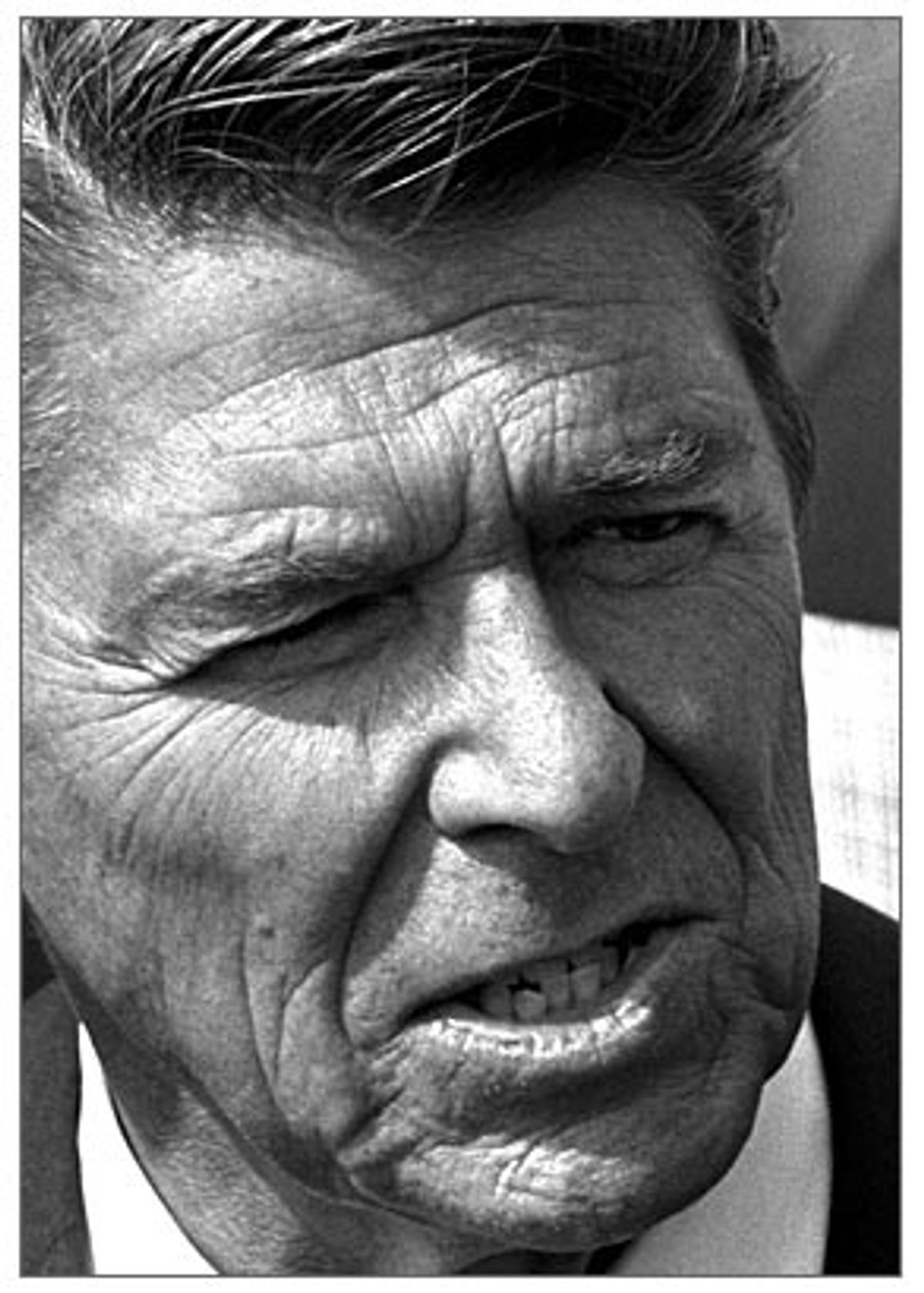

I feel bound to respect Ronald Reagan, as every American should -- not least because he chose a career of public service when he could have made a lot more money doing something else, and not least because he took genuine risks for peace. (President Bush, in contrast, seems to know only how to derange the world with war.) But in the necrophiliac orgy that is now upon us, there are three messages that I -- as a historian of the rise of the modern conservative movement in the 1960s, and as a reporter on the conservative regency in election year 2004 -- wish that more people would hear.

The first is that if Reagan's partisans succeed in creating an indelible memory of him as someone that everyone loved all the time, they will have won an important political struggle with consequences for today.

The second is that if his partisans succeed in minting Reagan in public memory as a repository of bedrock principle, they will have been complicit in letting forgetting win the battle against remembering -- because on their own, conservative terms, Reagan was often a sellout.

And last, if they manage to make the rest of us remember Reagan as the embodiment of the kind of genial conservative even a liberal could love -- a refreshing counterweight to the lunatic conservatives we have to deal with now -- they will have scrambled history instead of helping to inform it. Because Reagan was always much more frightening than the sunny optimist of now-popular legend.

The Reagan memory industry has been chugging along at full steam for over a decade now, from the successful attempt to put Reagan's name on the former National Airport in Washington to the (so far) unsuccessful ones to put his mug on the dime and Mount Rushmore. Do not mistake the deeply ideological thrust behind these campaigns. The aim is to make the notion that Reagan was the most beloved American politician ever seem self-evident -- and to make the kind of militaristic, minimal-government conservatism he championed seem just as natural.

For a short period at the beginning of his presidency, after John Hinckley's assassination attempt against him, and in the middle of his term, before the Iran-Contra scandal, Reagan was indeed stratospherically popular. But averaged out over his political lifetime -- Reagan first won office as governor of California in 1967, serving two terms prior to his two terms as president beginning in 1981 -- Reagan's popularity was, well, just average. Often, it was far below average.

When Reagan was governor, he worried about the "very dangerous precedent" of the state Constitution's recall provision being exploited by "well-organized groups for political recrimination." Yes, that's right. Though Reagan's latter-day acolytes led the lusty campaign to recall Democratic Gov. Gray Davis in 2003, Reagan would not have approved. And for good reason: He was the subject of two recall attempts himself. The first came in 1968, and it wasn't hard to understand why a group of liberal organizers, working on a shoestring, were able to obtain hundreds of thousands of signatures for his ouster: His approval rating was an anemic 30 percent. (In the next few weeks you are unlikely to hear that Bill Clinton and Ronald Reagan had roughly equivalent degrees of popularity during their presidencies, with Clinton's often higher, including when both left office.)

The activists in the second recall attempt weren't liberals, however. In 1967, Reagan, after campaigning, as he always did, as a tax cutter, passed the single largest tax hike in the history of any state up to that point. By 1971, some of his former supporters on the right had tired of what they saw as Reagan's serial betrayals of conservative principles and launched a recall movement of their own.

We didn't hear a lot about that movement when conservatives were dropping Reagan's name left and right in support of their bid to run Gov. Gray Davis out of Sacramento on a rail in large part because he had ... raised taxes.

Reagan's hagiographers, having their cake, eating their cake and smearing their cake all over the historical record, have a word for the occasions when this supposedly principled man violated his principles: They call them "pragmatism." But liberals have to give the man credit for his ability, unlike President Bush, to shift course when he was walking into a wall.

Still, it's too easy to convert the image of Reagan the pragmatist into a Reagan who wasn't really right wing. And from that it is but a short step to the most irritating Reagan myth of all: that he was nothing but a sunny optimist. Do not forget that he also frightened people with talk of apocalypse.

Reagan first came to public prominence as a political figure in the early '60s. The movie actor, hard on his luck, had become a kind of roving motivational speaker for General Electric. More and more, however, as he became more and more conservative, his talks focused on politics. Much of Reagan's stomping ground of Southern California had converted itself into a kind of McCarthyite petri dish, breeding paranoid patio dads and housewives by the thousands, each one eager and ready to find Reds beneath, beside and on top of every bed.

On any given weekend, interested citizens in Orange County could watch showings of films like "Communism on the Map" -- a geopolitical melodrama in which blood- or pink-colored ink leached over country after country, sparing only Spain, Switzerland and the United States (which was covered by a giant question mark) -- or find a study group assiduously poring over the organizational structure of what J. Edgar Hoover laughably called a "state within a state" -- the almost nonexistent Communist Party.

Reagan soon became one of the hottest tickets on the anti-Communist lecture circuit -- where sunny optimism was not the order of the day. "We have 10 years," he would say in just about every speech. "Not 10 years to make up our mind." (He was referring to the choice as to whether to embrace the Republican right or the march of communism, among whose avatars he numbered, in a famous 1960 letter to Richard Nixon, John F. Kennedy.) But "10 years to win or lose -- by 1970 the world will be all slave or all free."

Remember this: The hellfire never left him, and the hellfire ended up making the world a more dangerous place. As a candidate for elective office, even as president, his handlers always cleaned him up for popular consumption, but the same strange holdovers from the McCarthyite fever dreams continued to pop up in his discourse. One of his favorites was an invented quote of Lenin, popularized by the founder of the John Birch Society, to the effect that after the Reds took over Eastern Europe, they would "organize the hordes of Asia," as Reagan said in a 1975 interview, they would move on to Latin America and "then the United States, the last bastion of capitalism, [would] fall into their outstretched hands like overripe fruit."

Overripe words, yes, but also very characteristic of Reagan. It is a quirk of American culture that each generation of nonconservatives sees the right-wingers of its own generation as the scary ones, then chooses to remember the right-wingers of the last generation as sort of cuddly. In 1964, observers horrified by Barry Goldwater pined for the sensible Robert Taft, the conservative leader of the 1950s. When Reagan was president, liberals spoke fondly of sweet old Goldwater.

Nowadays, as we grapple with the malevolence of President Bush, it's Reagan we remember as the sensible one. At the risk of speaking ill of the dead, let memory at least acknowledge that there was much about Reagan that was not so sensible.

Again and again as president, Reagan let it slip that he concurred with fundamentalists' belief that the world would end in a fiery Armageddon. This did not hurt him politically. The kind of people offended by such talk had already largely abandoned the Republican Party. Those attracted by it -- evangelicals who had gone overwhelmingly for fellow evangelical Jimmy Carter in 1976 -- adopted Reagan, and his conservative Republicanism, as their own, and they never looked back. And in the eschatology of Cold War America, Christian apocalyptic thinking had everything to do with the assumption that the Armageddon would be a nuclear one, a confrontation with the anti-Christ bailiwick Russia, which Reagan identified in a March 1983 speech to the National Association of Evangelicals as the "Evil Empire."

No wonder that when, in November 1983, NATO launched a war games exercise code-named Able Archer, the Soviet Union misread its intentions as offensive and put its nuclear forces on alert, and the world came closer to ending than it ever had before.

It took this near miss -- and not, certainly, the largest mass demonstration in American history, the million people who gathered in Central Park in 1982 to demonstrate for a nuclear freeze (another moment you probably won't read about in all the Reagan eulogies) -- to get Reagan thinking seriously about negotiating an arms control agreement with the Soviet Union. To his enormous credit.

But he never did make a similar peace with the "welfare queens" he fabricated out of whole cloth to push his anti-compassionate conservatism. Nor with the African Americans he insulted by launching his 1980 presidential campaign in Philadelphia, Miss., where three civil rights workers were slaughtered by the Ku Klux Klan in 1964. Nor with the Berkeley students demonstrating in a closed-off plaza whom he ordered tear-gassed by helicopter in 1969.

Nor, last but not least, with the tens of thousands of AIDS corpses whose disease he did not even deign to publicly acknowledge until 1987.

As the eulogies come down the pike, don't let conservatives, once again, win the ideological struggle to determine mainstream discourse. Remember Reagan; respect him. But don't let them make you revere him. He was a divider, not a uniter.

Shares