D. and I were on the tar rooftop of my old studio in the Village, drinking too much and telling half-true stories -- the kind that made our lives sound more dramatic than they were. Too much red wine, too much beer, too much whiskey, too much of something I can't quite remember -- when her beautiful demon face lit up in a manner that was perfectly terrifying, paralyzing in the best sense of the word. That damn look. I think of it. I could feel it in my fingertips, behind my kneecaps, burning holes in my cheeks.

"You know what we should do?" she said.

"No."

"Let's run from your apartment to mine naked."

"No."

"Come on -- don't be such a pussy."

"I'm not a pussy."

"Yes, you are."

"Then why am I taking off my pants right now?"

"To show me your pussy?"

I'd like to tell you here that her apartment was in Spanish Harlem, or hidden along a bleak postindustrial stretch of Brooklyn, or smack in the middle of a neighborhood in Queens that even people in Queens have never heard of, and that sprinting from my apartment to hers in the buff was a truly epic feat of human idiocy. But I'd be lying. D. lived across the street from me, just a few strides away -- that's how we collided into each other in the first place.

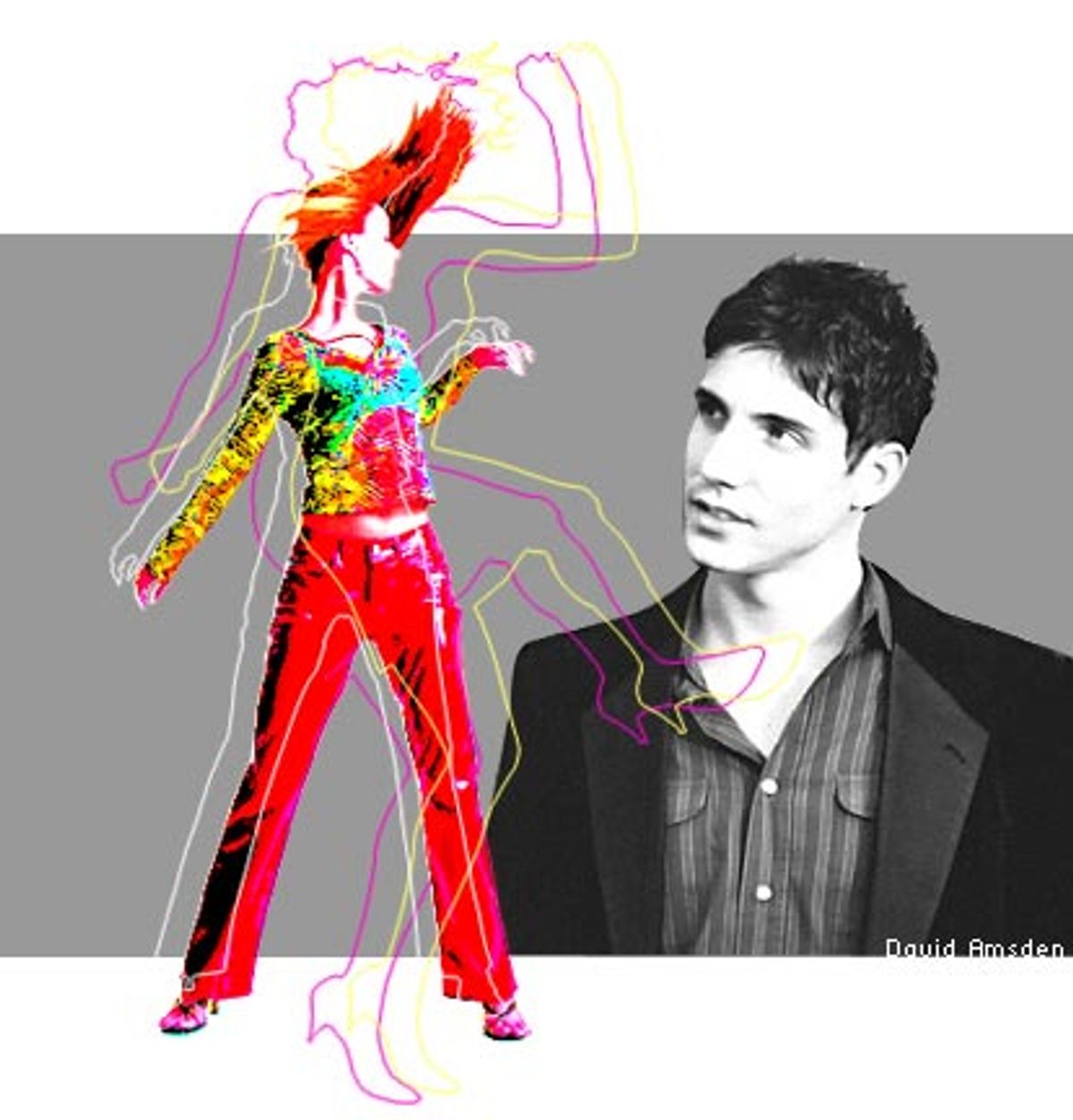

Over the previous three years I'd developed a pathetically obvious routine of sitting out on my stoop for two hours in the summer mornings, pretending to read a book while pretending to move a car I pretended to own, all the while waiting for D. to show up. She'd always be walking a hyperactive Jack Russell that (I'd soon learn) was a gift from a lesbian stalker. And wearing a pair of shredded-up sweats, a shredded-up tank top, tattoos poking out on all sides, gigantic colorful ones, tiny dark secretive ones. She had long red hair that went down to her ass, alabaster skin, a million random bracelets jangling on her wrists, glittery dark eyes, intimidating lips, a lethal swagger, and the sort of impossibly taut figure found only on people who dance in music videos for a living, which (I'd soon learn) is exactly what D. did.

Like this: Every day she'd show up, sauntering past me, oblivious to my existence. Then one day, for reasons I still can't comprehend, she approached. We talked: smiles stinging our faces, growing wider by the microsecond. It was one of these classic exchanges of banal questions that manage to feel fresh, dangerous even, because both parties involved are being attacked by the same brutal epiphany: that you want to take the other's clothes off, and commit sins. So, how long have you lived on the block? In the city? Is that your natural hair color? How about this humidity? Where are you from? Have you seen that one movie with Whatshisname? Are your parents still married? Do you eat meat? What's your name? What do you do? What do you really want to do?

At that time in my life -- I was 19 -- I answered phones for a vicious woman who had a simmering lump of coal where the rest us have hearts, a job that had me questioning my moral existence on an hourly basis, but I told D. that I wrote books and magazine articles, because I had a nasty habit of using strangers to test out optimistic incarnations of my future self. D. told me she was a dancer from New Jersey: a cheerleader for the Knicks at one point, then some stuff with MTV, then music videos full time, these days trying to break into acting -- most recently she'd played a junkie on a soap that got canceled before it ever aired.

"Cool," I said. "Not the canceled part, I mean. Shit, now I feel like an idiot. Um ... what sort of stuff with MTV?"

D. didn't respond immediately, which was jarring: This girl radiated verve, was immune to inhibitions, and here she was, suddenly coy, suddenly reserved, and all because of something as innocuous as MTV.

"Nothing," she eventually said.

"What's that mean?"

"It means I don't want to say."

"That's not fair," I said. "I just told you I answer phones for a heartless witch who makes me question my moral existence on an hourly basis."

"You said you were a writer."

"By writer I meant answering phones for a heartless witch. I probably should've made that clear."

She smiled. Then sighed, and said, "I was on 'The Grind.'"

"Holy shit!"

'It's ridiculous, I know..."

"Holy shit!"

"...but we do what we do and..."

"Holy shit!"

"...maybe you want to shut up now?"

This was the start of a cruel trend between us: D. had no idea what I was really trying to say, and I never got to tell her because back then my faculties of articulation were on a par with those of an inbred baboon. Everyone of a certain generation knows "The Grind": that show where Eric from the first "Real World" danced in a fake warehouse to forgettable hip-hop -- MTV's curiously irresistible cannibalization of "American Bandstand." It's a prime target for mocking now, but please: resist the urge. Those were different times in America, there was no Internet, and if you happened to be a jittery 14-year-old boy (as I was) there were few better places to go for a daily dose of damp, gyrating, half-clothed women than "The Grind." Everyday I'd come home from school after smoking a joint with my best friend, sprawl out in front of the TV, flip to "The Grind," stare at the girls, and do what young boys are prone to do in such scenarios: inventing personalities for those impossible women that all had something to do with their figuring out they loved me. Laugh if you must, I don't care: I had braces, I'd only kissed one girl, and all she did was wince and run away. Those were heavenly moments.

Anyway, the point here is this: The instant I learned that D. had been on "The Grind" I realized why just staring at her wrecked me so. My subconscious was being electroshocked. It was residual recognition, which is something no man should have to go through. To be confronted by archival masturbatory fodder in the form of someone you're flirting with, and hoping to maybe even date, is a lethal fusion of fantasy and reality -- of current expectations refracted through the malicious prism of early erotic nostalgia. Sitting on my stoop right there, I was no longer with the D. who lived across the street -- no, I was remembering the D. of my pubescent years. There she was, holding the mock-industrial railing on the upstairs balcony, camera in low and tight, sporting that minuscule red skirt and halter top, those pale thighs, those aggressive hips, all that relentless motion, all topped off by a wicked, distant expression on her face that had me praying to God that my mother didn't come home anytime during the next two minutes.

This was not a healthy situation.

We spent the rest of the day together, the rest of the week. I learned more about her: that she was bisexual, that she had gone to high school with Lauryn Hill, that she'd dropped out of college, that she'd been addicted to cocaine, that she'd been a background dancer in a few unfortunate workout programs that (of course) I also used to watch as a child. We started dating, striking up the sort of destructive relationship I was an expert at establishing in those days: where each person likes the other more than they ever let on, thereby driving each other mad, steering the whole enterprise into the flames. It didn't help that D. was a borderline schizophrenic: craving me one minute, squinting at me the next, as if she had no idea who this anxious young man was trying to kiss her in the back of a bar. Then again, maybe I have it all wrong. Maybe she was just a perfectly nice, perfectly normal girl, but I couldn't see this; I could see only her "Grind" persona, the bumping, grinding menace resurrected from my adolescence and superimposed onto the present.

Whatever the facts, this much is true: D. liked to drink, and when she drank she'd become a little unhinged, which drove me crazy, because like most people who have an ingrained fear of human connection, I'm most taken with those who seem on the verge of imploding -- or, at the very least, demanding that I strip down naked and run to her apartment.

Clothes off now, we sprinted down my stairwell, laughing, past the trash bags, past an elderly Colombian woman whose reaction was so blasé ("You no live on this floor...") that you'd think belligerent, naked kids could always be found traversing my building's stairwell. From there it was into the wretched little lobby, out the door, into the public domain. OK, so it was just across the street -- so what? Have you ever been naked in public? Have you ever been stared at by at least 14 people, one of whom is your landlord, one of whom is a 6-year-old girl who just dropped her ice cream cone, five of whom a family of splotchy, cornfed tourists reaching for their disposable cameras? Have you ever hated yourself for being so turned on by being so humiliated? Have you ever experienced this whole ugly vertigo because you were chasing pixilated lust in human form, all thanks to one of the most inane television programs in the history of cable?

I don't remember exactly what happened up in her apartment, things were blurry, it was dark, just that it was rough and clumsy and unrelenting and perfect and ridiculous and that we seemed to be attempting to do everything at once, because somewhere in our minds, beyond the haze of lust, past the veil of alcohol, we knew that our demise was near.

I've always envied authors who can write candidly about sex, the nuances, the various positions, the smells, the mistakes, the triumphs, because for me doing so is next to impossible: I reach this part of the story and my mind trembles, goes ballistic, becomes white space. I search for meaning, knowing it's there, but come up only with random motion, flashes of skin that are relevant only to the private confines of my mind. To me, this is a reflection of what's so great about sex: Everyone does it, and yet no one understands it. We're always hedging, looking for answers, coming up short, going back for more.

Anyway, that was the first time with D., which is all I was trying to describe here. There were others. And then, a few blinks later, there was nothing: We fought, we stopped talking to each other, we avoided eye contact on the street. It was like we'd made the whole thing up, that it only ever existed in fantastical memory form -- at least that's what it was like for me, which I guess makes sense, given the circumstances. In the years since I've moved away, but I still run into D. from time to time in the place where we first met: on TV, where I catch glimpses of her in a commercial, a sitcom, a music video. I watch, feeling dumb and mischievous, as if I know something profound, some secret, the absolute truth. And then it hits me: No, I don't. I don't know anything. I never did.

Shares