As he left Baghdad, Iraq, for appearances at the United Nations in New York and before a joint session of Congress in Washington, Iyad Allawi was seen on Iraqi TV flourishing a bandaged hand. News quickly flashed around Baghdad that this was not the result of enemy action. Bawling out an underling, Iraq's handpicked "interim" prime minister had bashed his fist so hard on the table that he had broken a bone.

That is not the least of Iyad Allawi's self-inflicted wounds. Accepting the poisoned chalice of appointment by the occupying power as their man in Iraq, he must now live with the consequences of a policy that has already reduced Iraq to ruins.

To those who know Allawi, news that his violence had extended to self-mutilation came as no surprise. While soft-spoken and polite to outsiders, he likes to rain abuse on underlings, cultivating an image of toughness that goes down well both with those Iraqis who nurture nostalgia for the days when Saddam made the electricity work and with his next-door neighbors at the U.S. embassy, who are gratified that they have found a "tough guy," as President Bush calls him, who will do as he is told.

Some Iraqis were experiencing Allawi's firm hand even as he accepted Iraqi "sovereignty" from former Coalition Provisional Authority chief L. Paul Bremer just before the latter scurried out of town in late June. These individuals were discovered in the compound of the Iraqi interior ministry being viciously tortured by policemen as a result, apparently, of an Allawi initiative to crack down on "crime." The Oregon National Guardsmen who made the discovery gave the victims first aid, while holding the torturers at bay and awaiting further instructions. The order that flashed from the U.S. military high command was unequivocal: Return the prisoners to Allawi's men and let them get on with the job.

Obviously those innocent Oregonians had not understood the nature of Allawi's mission, which was to put an Iraqi face on U.S. rule in Iraq, carrying out orders without deviating from orders emanating from the U.S. embassy. Thus situated, Allawi is right under the watchful gaze of John Negroponte, who knows a thing or two about administering subject territories behind the misleadingly bland title of "ambassador."

Infamously, from 1981 to 1985, Negroponte was the Reagan administration's proconsul in Honduras, which was then putatively ruled by the carefully selected and suitably nasty "strongman" Gen. Gustavo Alvarez. The task at hand was to crush by any means necessary the Sandinista regime next door in Nicaragua, using Honduras as a base for the exercise. To that end there could be no nonsense about democracy in Negroponte's fief. Instead, Hondurans were treated to rule by torturer and death squad, exactly the instruments now required in Iraq, which is doubtless why this sinister apparatchik was selected for his present post.

Iyad Allawi, meanwhile, is no less perfectly cast in his role, given his lifelong record of serving the needs of various shadowy patrons. He acknowledges having been on the payroll of six intelligence services over the years, principal among them the British, Saudis and CIA -- not to mention his original patrons in Saddam Hussein's Baath Party. Among the attributes that has recommended Allawi to his patrons is his readiness to tell them what they have wanted to hear, which, in the 1990s at least, consisted mostly of ever more fanciful tales about goings-on in Iraq. Sometimes his willingness to oblige by supplying bogus intelligence reached ludicrous proportions. On April 1, 1995, for example, while Allawi's Iraqi National Accord organization was headquartered in Amman, Jordan, the Arabic newspaper Al Hayat ran an April Fool's Day report that Saddam had decided to have himself cloned and had already had his son Uday cloned to test the procedure. A journalist visiting Allawi's office made joking reference to the story, only to be instantly informed that "we were first with that intelligence -- we sent it to Washington weeks ago."

Experiences such as this did not disenchant the paymasters in London and Washington. Even the unmitigated disaster of Allawi's attempt to mount a coup against Saddam in 1996 did not cause them to fall out of love. On the contrary, they reached for Allawi for further fictions when needed. Hence it was Allawi's organization that furnished news that Saddam had biological weapons on 45-minute standby, the ludicrous claim so eagerly broadcast by Prime Minister Tony Blair as a justification for war.

Returning to Baghdad in the wake of the U.S. Army last year Allawi sat quietly while his hated rival (and cousin) Ahmad Chalabi steadily lost the support of his erstwhile patrons in Washington. While Chalabi's simultaneous efforts to rebuild his family fortunes were high-profile, Allawi stands back from the trough. In fact the cousins' long-standing and bitter political enmity extended to the business sphere, including a nasty squabble over who garnered the potentially very profitable Iraqi agency for the Swiss oil trading giant Glencore. (Allawi eventually won.)

Finally, last June, the old Baathist came to his reward, when he was appointed as "interim prime minister." (The non-interim variety is due to be installed sometime in 2006 once an elected assembly has ratified a new constitution.) Among the tableaux vivants mounted by the U.S. to assure the world that sovereignty had passed to Iraqis was the arraignment of Saddam Hussein in front of an Iraqi judge. The U.S. military command packed the courtroom with military personnel, ejected the only Iraqi journalist who had gained admission and, despite the orders of the judge, confiscated audiotapes of the proceedings. For Iraqis, the message was clear. Sovereignty in Iraq still came out of the barrel of an M-1 Abrams tank gun.

Allawi himself, no fool, may understand that the only way to garner legitimacy in the eyes of Iraqis is to indicate an independence from the U.S. But he also knows perfectly well that something nasty happens to Iraqis on the American payroll who turn against their sponsor -- and if he forgets, he only has to look at what happened to Ahmad Chalabi. Thus, when Negroponte vetoed Allawi's sensible effort to offer amnesty to resistance fighters, he promptly caved. Nor has he shown any reluctance to pursue the disastrous war on two fronts, confronting both Sunni insurgents in Fallujah and Shiite adherents of Muqtada al-Sadr. Meanwhile, the vicious and ruthless insurgency swamps the occupation in a tide of blood. Hundreds have died this month alone, while the U.S. hastily diverts to security $3 billion originally intended, at least in theory, to better the lives of ordinary Iraqis.

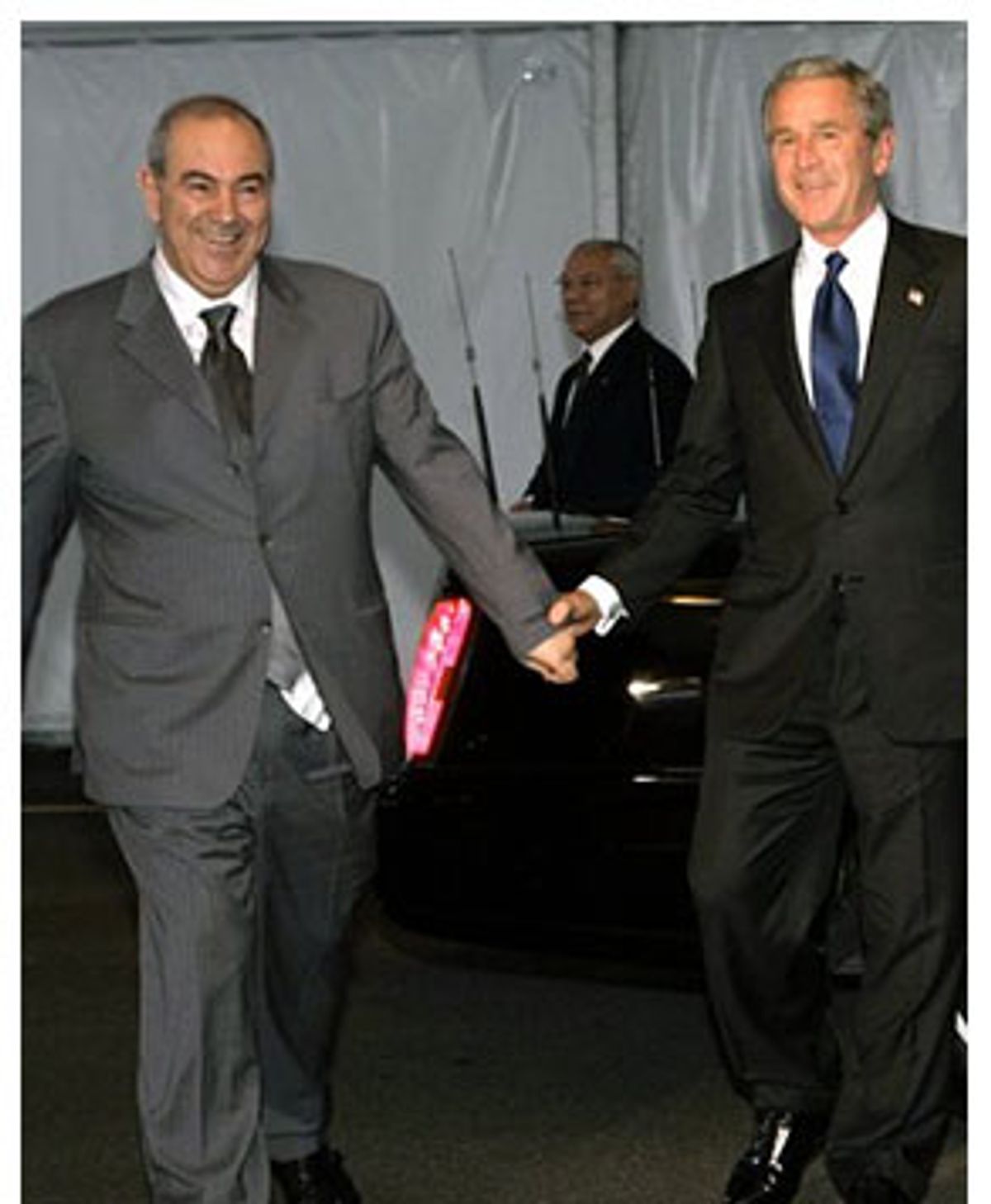

That is why Allawi's mission to the U.S. this week is so important, at least for George Bush. He must help convince Americans to disregard the facts and accept the notion that all is well in Mesopotamia. Yesterday our Iraqi client showed that he knows what is expected of him, dutifully declaring, "We are winning, we are making progress in Iraq, we are defeating terrorists." Iraqis know better, but who cares what they think?

Tomorrow, Allawi is hosting a press conference in New York for Arab journalists. All questions must be approved in advance.

Shares