For a kid, one of the biggest joys of Halloween was that moment when you'd first arrive home from an evening of trick-or-treating and get to dump the contents of your pumpkin-faced bag onto the living room floor. Sorting out the big-ticket items from the eye-rollingly lame handouts was never too difficult. Pack of Smarties: thumbs up. Unwrapped apple: straight to the trash. Mini Krackle: eat immediately. Pennies: you've got to be kidding. But what about the Gospel literature?

This year, as they sift through their loot, many little Batmen and Dora the Explorers might find verses from Deuteronomy or First Corinthians among the candy corn. That's because many Evangelical Christians, who have always had a shaky relationship with occult-laden Halloween, have decided that instead of boycotting the holiday, they're going to take advantage of it to spread their message of salvation through the acceptance of Jesus Christ. "There are few occasions when you have people coming to your door, asking you for things," says Geoff Dennis, vice president of publishing services for Good News Publications, which turns out 8 million Halloween-themed gospel tracts each year. "So it provides easy access to sharing the Good News that we have."

"We're always looking for chances to share our faith," says Mark Brown, vice president of marketing for the country's oldest tract publisher, the American Tract Society. "This is the only time of the year you can do this legally." While it has been done for years among Evangelicals, the number of folks who answer the door with gospel tracts as well as M&Ms and bite-size Milky Ways seems to be steadily increasing.

"Our tract sales have grown by leaps and bounds," Brown says, noting that ATS sold 3.5 million tracts this year, a 10 percent increase since last Halloween. "For a long time, Christians have tried to ignore the holiday or go to an alternative event, like a carnival. Now we'll see them passing out tracts at the carnival or sitting on their porch with the light on and a stack of tracts. They're choosing to be visible. And the beauty of Halloween being on a weekend this year -- more people are home, so there'll be way more participation."

The tracts themselves are designed to speak directly to kids, filled with brightly colored cartoon illustrations and written with the lively colloquial tone of a Saturday morning PSA. ("Costumes are cool, but Heaven is awesome!" reads one ATS tract. Another, which calls Jesus "the ultimate superhero," tells kids to "Look at His birthday on the calendar. It's Christmas!") Good News makes ample use of puzzles and word games ("If there are activities, kids are much more engaged," Dennis says). And ATS has its finger on the pulse of kid culture, featuring popular characters like Spider-Man and Harry Potter on its tracts. (The "Finding Nemo" tract retells the story of the hit Disney film through a Christian lens: "God loves you just as Marlin loved Nemo [but] Nemo's sin separated him from his father.") The biggest and most recent innovation has been the direct packaging of tracts with candy, stickers or sometimes small toys, à la Happy Meals.

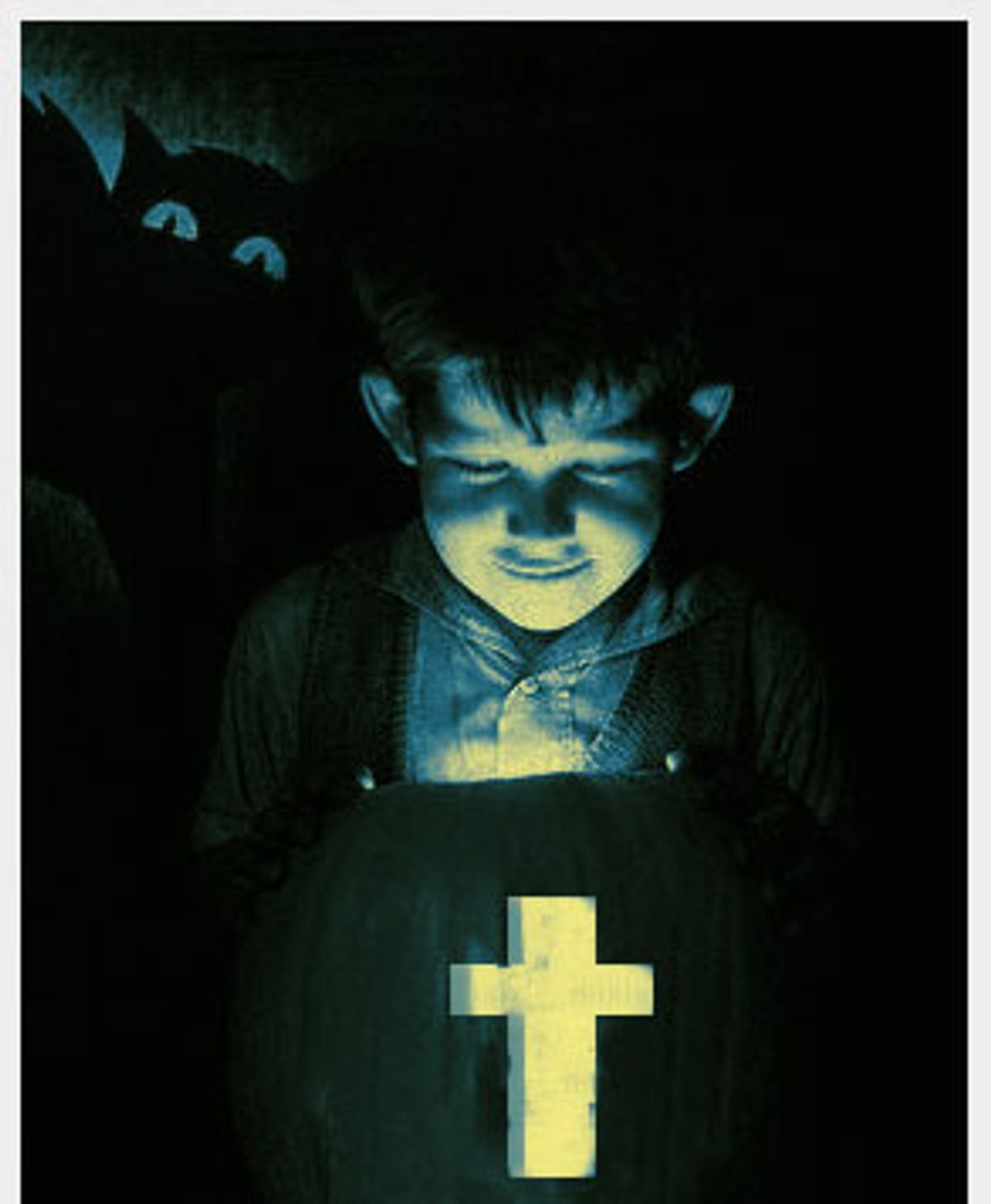

Publishers agree that retaining the treat is important to the tract's acceptance by children. "Kids are out there looking for candy," Brown explains. "If you hand them a tract and nothing else, they'll have a negative feeling toward you and toward the tract. So you want to give a really good piece of candy; don't gyp the kid out. Then when they dump the bag, their eyes just pop out, and they associate this with the candy."

Both companies tout the success of their approach, claiming thousands of positive responses each year by phone, letter and e-mail. And both are careful about encouraging a responsible use of their tracts. ATS even posts lists of dos and don'ts on its Web site, including tips like "Don't force tracts on people," and "[Do not use one] if the tract could be interpreted as a personal attack" or "when it may needlessly offend someone." Still, the pairing of the word of God and the word of Hershey does not sit well with everyone. The Rev. Astrid Storm, an Episcopal priest at Grace Church in New York, who calls the practice "back-door evangelism" says, "I loathe making a connection between Christianity and getting goodies. It's not the best connection to make at the outset of one's faith, since it hardly equips one to deal with the many disappointments and setbacks that are an inevitable -- and important -- part of the Christian life."

For the Rev. Winnie Varghese, a chaplain at Columbia University, it's the bigger picture that matters. "If it's OK for Muslim families to put tracts proclaiming the tenets of Islam into trick-or-treat bags or for more liberal denominations to pass out literature saying that you can be gay and still be a good Christian, then [the Evangelical Halloween tracts] are fine, too," she says, "but I suspect it wouldn't be OK in those cases. We always give a certain amount of space to Evangelicals that we don't give to other denominations."

"Still," Varghese adds, "we understand the Evangelical impulse that they must lead as many people as possible to Christ. In that belief, they are ethically bound to do so."

And that sums up the mission of the tract publishers exactly. "Halloween is typically affiliated with ghouls and demons and witches, kind of the dark side," Dennis says. "And Christians are commanded to be light in darkness."

Dennis, whose grandparents founded Good News in 1938 with the belief that "the Gospel message deserves an excellent package," distributes tracts from his own home in Wheaton, Ill., on Halloween and admits that he has occasionally been met with a less-than-positive response. "On occasion, there's somebody who'll get upset that we're propagating the Bible's message to people who may not want their kids to hear it," he says. "And, you know, the great thing is, we live in a country that allows for that freedom." (Though neither the American Civil Liberties Union nor Americans United for the Separation of Church and State gave official comment on the topic, both organizations responded to Salon's inquiry by acknowledging the legal right of people to hand out religious literature from their own homes.) "In addition," Dennis adds, "we'd encourage parents to look through the contents of any child's candy bag and remove anything they don't want."

Dennis also points out that writing and designing a truly successful tract means maintaining a difficult balance between the Christian message and Halloween imagery that is often in opposition to church teachings. "We have to keep two audiences in mind," he says. "Our goal is to provide a tract that is palatable to both the Christians who buy them and the end user it is intended for. A tract that has a ghoul on the cover might really speak to a kid who's been dabbling in those kinds of things, but we may not be able to sell that to the Christians. We stay away from the occult stuff and tend to use more innocuous costumes, like pirates."

Another publisher, perhaps the most controversial producer of gospel tracts, is not as concerned with making such distinctions. Chick Publications, founded in the 1960s by Christian cartoonist Jack Chick, does not shy away from horror imagery in the slightest, instead churning out hundreds of comic strips replete with good old fire-and-brimstone evangelism. One tract, "Devil's Night," in which a young girl's teacher berates her for not wearing a monster costume to school on Halloween, illustrates the pagan origins of the holiday with images of the Celtic lord of the dead calling souls to him. Another -- titled "Boo!" -- features a chainsaw-wielding Satan chasing campers through a forest and again tells the origins of Halloween, this time with an image of hooded Druids about to sacrifice a kidnapped virgin.

"Some of our tracts may be more in your face than others," says Chick representative Karen Rockney, "but that's why we have a large variety of tracts. All tracts are not for everybody. And we get plenty of letters from people who say, 'I never would have been saved, never gotten the message' if we hadn't been in your face."

Groups like ATS are quick to point out the less-graphic nature of their own tracts. "Nobody likes to be told they're going to hell in a handbasket," says ATS's Brown. "They appreciate images they can relate to, that can express the simple message of the Gospel."

"We want to be careful not to use scare tactics, not to use fear as a motivator, to focus on a very positive message," says Dennis of Good News. "Having said that, God can use anything to draw people to Himself."

Halloween is an evolving holiday, and it's being pulled in two directions. Some people are flocking to their houses of worship to enjoy extravagant Bible-friendly festivals complete with games, prizes and rides. Some are still embracing the classic fright-fest, decked out with buckets of sweets, orange lights and animatronic Frankensteins. Both groups have contributed to the $3.12 billion that will make this coming Sunday the most lucrative Halloween ever for the holiday merchandise industry. "Yes, Halloween is changing," says ATS's Brown, "but we don't want it to change too much. Then we won't have people coming to the door anymore."

Which brings us to a third, distinctly different point of view on the holiday. Daisy Casillas, a 30-year-old Web designer in Jacksonville, Fla., spent past Halloweens waiting for trick-or-treaters with candy and Chick tracts at the ready, something she's decided to forgo this year. "I've decided not to even buy Halloween candy, because it gives manufacturers the message with my dollars that I celebrate it; and I don't. I just won't answer the door. Imagine if every so-called professing Christian in America did not answer the door. There would be no Halloween if it didn't make money."

Shares