I found myself across a table from Yasser Arafat eight months ago. The Israelis had just assassinated Sheik Yassin, the leader of Hamas, and word got out that Arafat was going to hold a rare press conference. So I went to the Muqata, the smashed-up Palestinian Authority headquarters in the West Bank city of Ramallah. Along with a few dozen reporters and photographers, I waited for Arafat to come out in a courtyard outside the half-destroyed building. The Palestinian flag waved over its shattered, shell-pocked walls, near a huge pile of cars crushed by IDF tanks. The Israelis had blasted the compound, an old British army headquarters from the Mandate days, when they invaded the West Bank in 2002 in reprisal for Palestinian terrorist attacks. During a month-long siege, tanks fired on his office. Arafat and his associates were confined to two rooms in the building. He had remained an effective prisoner ever since.

Arafat never came out, but after a couple of hours there was a commotion and all the photographers got up and started going in through the sand-bagged entrance. My Palestinian guide told me to quickly mingle with the crowd and try to go upstairs. One of Arafat's elite Force 17 guards, a handsome, vaguely Italian-looking guy with a machine gun slung rakishly over his shoulder and wearing combat fatigues that looked as if they had been tailored, took one look at my tiny camera, waved his finger and said, "Only photographers. I know you are a writer." But I kept shuffling forward and he must have decided it wasn't worth the trouble to stop me. We climbed through a confusing maze of stairs and turns, past dull dirty walls of institutional concrete. Then we found ourselves milling outside a medium-size room where Arafat, Palestinian Authority Prime Minister Ahmed Qureia and other Palestinian leaders were greeting some European visitors.

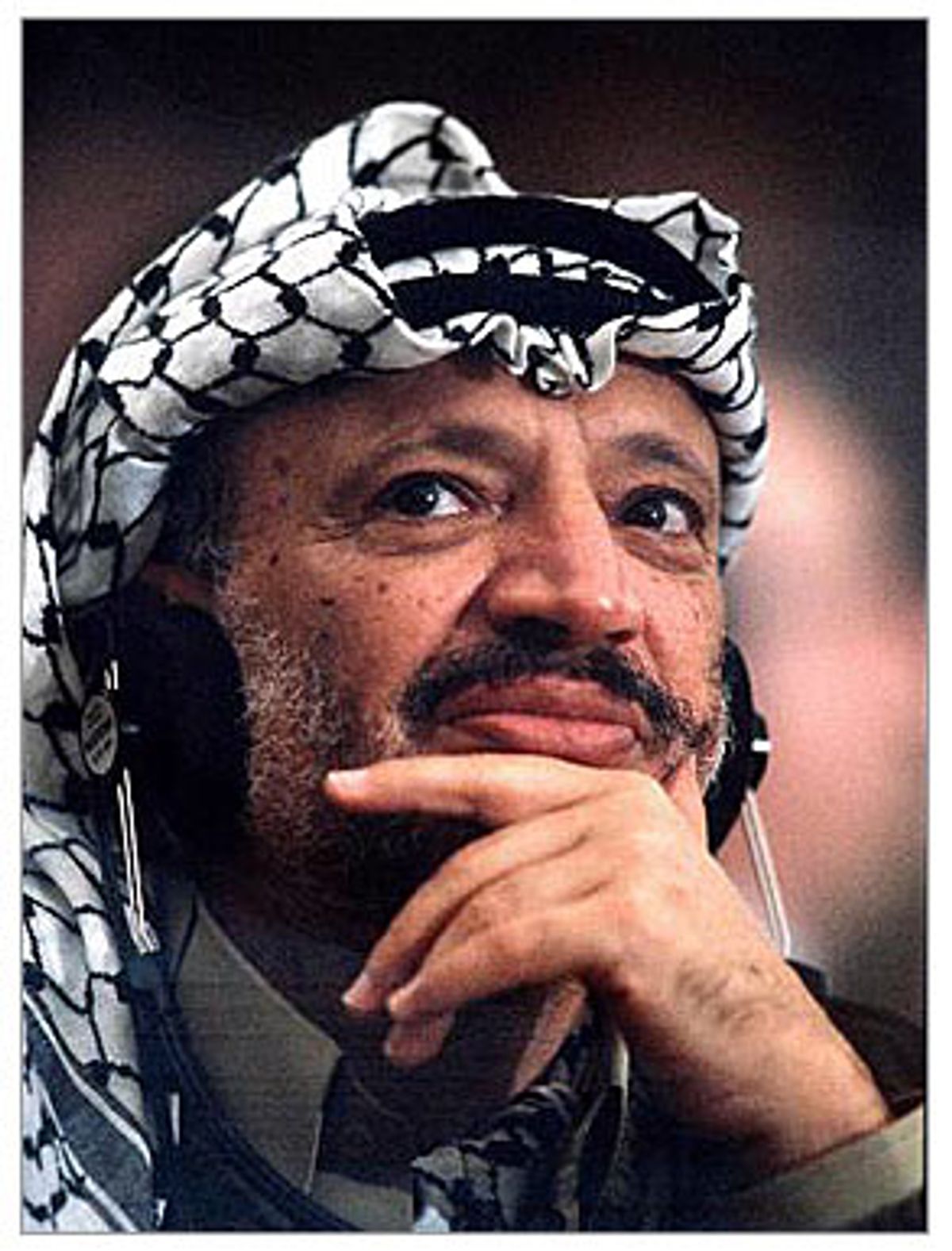

There he was, Mr. Palestinian, guerrilla warrior, Nobel Peace Prize winner, terrorist, president, the most famous national liberation movement icon in the world, in Israel a man almost as hated as Hitler, the most argued-about significant non-state leader of the last century, sitting 20 feet away, and no one had even searched me. Arafat sat on the other side of a long table, a small, frail-looking man, beaming at his visitors. He was talking about his life under quasi-house arrest. "I am living here," he said in a quiet voice in which resignation mingled with mischievousness, "sleeping here, eating here..." But I never heard what Arafat said next, because at that moment one of the guards pulled my arm and gestured brusquely to the door.

Eight months later, Arafat is dead. The Palestinian Authority left the surreal ruins of the Muqata intact, intending it to serve as a symbol of Palestinian summud, steadfastness. But it is hard not to see in those shattered walls a darker metaphor for the career of Yasser Arafat. Arafat ended his life a virtual prisoner, his secular movement challenged by radical Islamist groups, his people still living under the longest military occupation of the 20th century, his dream of a viable Palestinian state still only a dream. Ordinary Palestinians fed up with his incompetence, cronyism and corruption had long stopped expecting anything from him, even though they still regarded him as an icon. Had it not been for the Israeli incursion, which turned him yet again into a victim, his star among his own people would have waned still further. In historical terms, Arafat was a loser.

And yet, just as the bullet-riddled Muqata still stands, Arafat's legacy endures. That legacy is ambiguous and problematic, yet its central achievement is undeniable: For almost 40 years, Arafat kept alive -- sometimes with violence, sometimes with statesmanship -- the simple idea that a Palestinian people existed. This fact is now acknowledged by the world, but it took a bitter struggle for that to occur. For decades, Israeli leaders, who correctly saw in the very notion of "Palestinians" an existential challenge to the idea of a Jewish state, rejected it or dismissed its significance. (Golda Meir, who like so many other Israeli leaders insisted that Jordan was Palestine, famously said, "There is no such thing as a Palestinian people.") Arafat and his guerrillas forced the world -- using violence, sometimes appalling violence -- to recognize that Palestinians existed, that they had been unjustly exiled from their homeland, and that their grievances needed to be addressed.

It is understandable that Americans have never found it easy to think about Arafat -- and not just because his goal of Palestinian independence challenged the myth that Israel's creation was innocent. (It remains perhaps the most painful moral irony of our time that history's ultimate victims, the Jews, victimized another people in the process of creating their state.) His career defies comfortable moral assumptions. He was a statesman and a terrorist, a guerrilla leader and a politician. The idea that terrorism, seen from a historical perspective, could serve a legitimate political purpose is not easy to swallow -- and to argue that position has become taboo after 9/11. Yet our position has no moral consistency. We claim to subscribe to Kant's categorical imperative, to treat humans as ends, not as means, but we live in a world of ends where the bloody traces of the means are quickly forgotten. We celebrate French Resistance fighters, or Mandela's African National Congress, or the Jewish terrorists who would later become Israeli statesmen, like Menachem Begin and Yitzhak Shamir, or any other "terrorist" group whose cause we support and who ends up victorious. But this is not easy to acknowledge. How much easier simply to denounce Arafat as a terrorist and murderer.

Which he was. But there are no clean hands in the Middle East.

Benny Morris, one of Israel's so-called new historians (the term refers to those younger academics who rejected the official propaganda that dominated Israeli historiography until the late 1980s), concisely summed up the moral ambiguity that surrounds Palestinian terrorism. "In retrospect, the various Palestinian campaigns from the late 1960s through the 1980s outside the Middle East had a dual and contradictory effect," he wrote. "They put the 'Palestinian problem' on the world agenda while substantially undermining sympathy for the Palestinian cause; the terrorist outrages were both useful and important to the cause while at the same time putting it into disrepute."

It was Arafat's fate to never be able to entirely free himself from this duality. The man who in 1974 famously proclaimed to the United Nations "Today I have come bearing an olive branch and a freedom fighter's gun" was never able to convince the only two countries that mattered, the United States and Israel, that he was fully committed to the olive branch. To be sure, both of those nations bear a large measure of responsibility for this. As another one of the Israeli new historians, Avi Shlaim, notes, both Israel and the United States consistently refused to trade land for peace -- even after Arafat felt sufficiently strengthened by the first intifada to finally recognize Israel's legitimacy in 1988. Both of them demonized him and his movement, the PLO, as eternal terrorists, bent on Israel's destruction. By the time the United States finally accepted the idea of a Palestinian state, and bent to reality in recognizing the PLO, Islamists far more implacable and opposed to Israel than Arafat had grown in power.

But Arafat, too, must take his share of the blame for the failure of the peace process. Time and again, he failed to make the bold moves that might have broken the logjam. It was never a viable option for the PLO to confront the rejectionists Hamas and Islamic Jihad militarily -- that would have meant a full-scale civil war -- but he could have marginalized them if he had been a better leader. Unwilling to either rule out the military option or embrace it, he was a master tactician who seemed never capable of delivering the bold strategic stroke. (In that sense, he resembled his ancient nemesis, Ariel Sharon, a brilliant field general who lacks a larger vision.) Danny Rubinstein, the Haaretz correspondent who has covered the Palestinians for years, noted on Thursday that Arafat could not resist the siren song of the Palestinian street: If it called for violence, he delivered violence. "This was his weak side. This is how it came out," Rubinstein says. "He always felt it necessary to speak to his people such that they would continue to embrace him, to esteem him, to idolize him, and, most importantly, to obey him."

The greatest question mark about Arafat concerns the failed Clinton-brokered 2000 peace talks with Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak. There is zero historical consensus on who was responsible for the breakdown of the talks that began at Camp David and came tantalizingly close to succeeding at Taba. Even what was actually offered is disputed, but it involved giving the Palestinians about 95 percent of the West Bank and all of Gaza, with Israel retaining the large settlement blocks along the 1967 border. The Palestinians were not given full sovereignty over the Old City of Jerusalem -- home to the holiest site in Judaism, the Wailing Wall -- and the Palestinian refugee issue was left vague, but with the clear understanding that only a few would be able to return to Israel proper.

The mainstream Israeli and American view is that Arafat rejected the most generous offer that Israel would ever make the Palestinians. Many Israelis, perhaps most, believe that this proved that contrary to his words, Arafat never had any intention of making peace with Israel and was intent on eventually destroying the Jewish state. Palestinians and some other analysts say variously that the offer was fatally flawed because it would result in a series of fenced-in Bantustans, that Barak never really offered it, and that the United States and Israel, in their haste to get a deal, failed to establish the trust necessary for negotiations to succeed. They also point out that Palestinians did not break off the negotiations at Taba: They came to an end when Ariel Sharon, who had vowed not to pursue the peace plan, was elected.

Perhaps the best judgment was rendered by the Israeli journalist Tom Segev, who simply noted that issues as intractable and complex as the Israeli-Palestinian conflict are rarely resolved at a single throw.

At the end of his life, although he still held all effective Palestinian power in his hands, Arafat had come to serve a purely symbolic function. That function was sentimentally useful: Arafat represented the last hope for the hundreds of thousands of Palestinian refugees around the world, still holding their yellowing deeds and keys to houses in Jaffa, Haifa and Jerusalem to which they will never return. But practically, it was an encumbrance. He was a statue, a myth, and his larger-than-life stature blocked a new, more pragmatic generation of Palestinian leaders from emerging. Those leaders will make the same demands Arafat did -- a contiguous state in most of the West Bank, a Palestinian capital in East Jerusalem, shared sovereignty over the holy sites, some fair resolution of the refugee question that does not spell the end of Israel. But perhaps they will actually be able to achieve them.

It does not, of course, depend only on the Palestinians. If all the engaged parties -- the Palestinians, the United States and Israel -- seize the moment, the Palestinian state Yasser Arafat dreamed of could come into being. If it took his death to make that happen, that would only be the final uncanny twist in a life and career full of them.

Arafat was born in 1929, 19 years before the state of Israel came into existence. The place of his birth, like almost everything else about him, is disputed: Arafat liked to claim he was born in Jerusalem, but most authorities agree that in fact his birthplace was Cairo. (It is one of the many ironies of Arafat's life that neither the birth nor the death of the father of Palestinian nationalism occurred in Palestine.) His father was a middle-class merchant in Gaza. Arafat studied civil engineering at Cairo University; after the creation of the state of Israel amid war and the attendant expulsion of 700,000 Palestinians, he moved to Kuwait. There he and other Palestinian exiles established the Palestine National Liberation Movement, also known as Fatah, dedicated to reclaiming historic Palestine (the land bounded on the west by the Mediterranean and the Sinai, and on the east by the Jordan River and the Dead Sea) from Israel by the use of force.

Arafat's innovation was to insist that the Palestinian struggle was a Palestinian affair, not part of a pan-Arab struggle. Salah Khalaf, another founder of the movement, recalled, "Yasser Arafat and I ... knew what was damaging to the Palestinian cause. We were convinced, for example, that the Palestinians could expect nothing from the Arab regimes, for the most part corrupt or tied to imperialism, and that they were wrong to bank on any of the political parties in the region. We believed that the Palestinians could rely only on themselves."

After years of preparation, Fatah's first military action took place on Jan. 2, 1965, when a squad of guerrillas crossed the border and unsuccessfully attempted to blow up a water line in the Negev Desert. Although Jordan and Egypt, fearing being dragged into a war with Israel, tried to suppress the movement, Fatah's military wing succeeded in carrying out about a hundred raids before the outbreak of the Six-Day War in June 1967. Fatah and Arafat gained standing with Palestinians because of their militancy, and Arafat was named head of the new Palestine Liberation Organization, which had been born in 1964.

The PLO's charter stated that Palestinians had the right to return to their country, declared the 1947 United Nations partition null and void, and asserted that "armed struggle is the only way to liberate Palestine." Saying that its goal was "the elimination of Zionism in Palestine," the PLO denied that Jews had any historical claim on Palestine.

After the 1967 Six-Day War, which inflicted a crushing defeat on Egypt and Syria and resulted in Israel's occupying the West Bank and Gaza, Arafat and the PLO decided to continue their guerrilla war. This time, however, the war was to be waged from inside Israel or the occupied territories, not from neighboring Arab states. Arafat attempted to use guerrilla raids to instigate a popular uprising in the West Bank. The bloodiest attack killed 11 and wounded 55 Israeli civilians in Jerusalem in 1968. But the raids were largely ineffective and the Israelis crushed Fatah, killing 200 operatives and arresting 1,000. Israeli reprisals against West Bank towns weakened popular support for the guerrillas: In November 1967, for example, Israeli forces demolished all 800 houses in the village of Jiftliq. Moreover, the traditional Palestinian leadership in the West Bank did not back the militants and was co-opted by the Israelis. The war of national liberation never materialized. Arafat, who had been moving between West Bank safe houses and back and forth across the Jordanian-West Bank border, narrowly escaped being captured by the Israelis, who on one occasion burst into his hiding place and found a warm bed and water still boiling for tea.

Driven into Jordan by Israeli strikes, Fatah and other guerrilla groups, the most significant of which was George Habash's PFLP, became a virtual state within a state. Fatah's prestige among young Palestinians rose dramatically after the battle of Karameh, in which Arafat's guerrillas, or fedayeen, fought fiercely against an overwhelmingly superior Israeli force. After the battle, Fatah's numbers swelled from two or three thousand to 10-15,000.

As was to happen repeatedly throughout his career, Arafat's militants came into bitter conflict with the Arab states in which they were based. (In Lebanon, they also clashed with the people.) The new power of the Palestinian guerrillas increasingly threatened the ruling Hashemite dynasty, headed by King Hussein. When the PFLP, which openly questioned the need for Hashemite rule, hijacked four international jets -- a move opposed by Arafat and the majority of the PLO -- Hussein decided it was time to get rid of the Palestinian resistance groups once and for all. In a 10-day virtual civil war, Jordanian troops killed close to 2,000 fedayeen and many thousands of innocent refugees. The battle of "Black September," as Palestinians called it thereafter, concluded with the militants' expulsion from Jordan.

Deprived of a haven in the nation sharing the longest border with Israel, Arafat, Fatah and the other resistance groups moved to Lebanon and Syria, where they began to stage attacks on Israel across the border. While Arafat's Fatah faction continued with its tactics of infiltration, the more radical of the fedayeen embarked on a new strategy of attacking Israelis anywhere around the world. Aerial piracy was their most spectacular tactic. The PFLP and another rejectionist group, Ahmed Jibril's PFLP-General Command, hijacked numerous planes, planted bombs on others, and launched bloody attacks at airports, embassies and Jewish private organizations around the world. The purpose of the attacks was both to terrorize Israelis and to draw the world's attention to the existence of the Palestinian cause. Between 1968 and 1977, Palestinian groups hijacked or attempted to hijack 29 aircraft. The most infamous attack took place during the 1972 Olympic Games at Munich, when Palestinian terrorists from the Black September organization took nine Israeli athletes hostage. All the Israelis were killed by the Palestinians during a botched rescue attempt.

Black September, founded in 1971, was an offshoot of Arafat's Fatah; according to Morris, pressure from Palestinian extremists drove Arafat and the PLO to embrace international terrorism. "The moderates apparently acquiesced in the creation of Black September in order to survive." For three years, the group led a surge of international terrorism committed by Palestinians: In 1973, 60 terrorist attacks erupted outside Israel and the occupied territories, compared to two in 1968. In 1973, the PLO closed down Black September, deciding that international terrorism was hurting the Palestinian cause. The decision was influenced by the 1973 October War between Egypt and Israel, which put the Palestinian problem back on the world's agenda. In 1974, the PLO formally renounced international terrorism.

Morris notes, "Without doubt, Arafat recognized the value of the terrorist splinter groups; they could be relied upon both to keep the Palestinian issue alive and to hurt Israel -- while he himself could denounce these groups as anti-PLO renegades, or at least dissociate himself from their actions." But the terrorist tiger proved hard to get off. Arafat's opportunistic, on-again, off-again relation with international terrorism was evidence of a pattern that was to recur throughout his career -- and in the end led to his diplomatic isolation.

In 1978, President Anwar Sadat of Egypt signed the historic Camp David peace treaty with Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin, a treaty that returned the Sinai to Egypt and ended hostilities between Israel and the most powerful Arab state. Arafat and many Arab states immediately denounced it; with Syrian President Hafez Assad, he released a communiqué announcing that they would "apply all their resources to the elimination of its consequences." This stance made sense from the Palestinian perspective. Although the Camp David treaty was seen as a historic breakthrough by Americans and many observers, it had a fatal flaw: It was essentially a separate peace between Israel and Egypt that completely failed to address the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, in particular the central issue : Israel's occupation of East Jerusalem and the West Bank, which it had conquered in the 1967 war. Begin, for his part, had made it clear he had no intention of giving up any of the West Bank, which he regarded as part of the biblical Eretz Israel and referred to as having been "liberated." Begin insisted that the Israeli military remain. He proposed "autonomy," a euphemism for very limited Palestinian self-rule in the West Bank and Gaza, and rapidly expanded the building of settlements. His agriculture minister, Ariel Sharon, was in charge of much of the Israeli expansion into the West Bank and Gaza. Sharon stated that the entire West Bank would have to be populated with not less than 300,000 Jews to serve as Israel's permanent "security shield."

Over the next 25 years, while peace plans came and went, Sharon succeeded in implementing his plan. Although large numbers of Israelis saw the Camp David peace plan as providing a historic opportunity to make peace with the Palestinians and dissented from these aggressive settlement policies, Begin -- and every successive Israeli leader -- continued to implement them.

Sadat also turned away from the Palestinian cause. Enraged at Palestinian terrorist attacks, in particular the murder of the editor of the leading Cairo newspaper, al-Ahram, by a radical breakaway faction headed by Abu Nidal, Sadat told Israel that there should be no Palestinian state and that the West Bank should be ruled by Jordan, Israel and local representatives.

Howard M. Sachar, the author of a standard history of Israel, quotes Palestinian scholar Fayez Sayegh, who sums up Begin's position thus: "A fraction of the Palestinian people ... is promised a fraction of its rights (not including the national right to self-determination and statehood) in a fraction of this homeland ... and this processs is to be fulfilled several years from now, through a step-by-step process in which Israel is to exercise a decisive veto power over any agreement."

It is impossible to understand Arafat's career, or his many mistakes, without taking into account the implacable resistance his movement faced from both Israel and the United States. Some of that resistance was legitimately based on the terrorist acts committed by the PLO. But the Israelis also used "terrorism" -- in the Israeli press, often used as a virtual synonym for "Palestinian" -- as an excuse to avoid dealing with the underlying issues. As the Israeli writer Amos Elon has noted, the tragedy was that the Palestinians triggered an existential fear of extinction in Israelis, many of whom had just escaped Hitler's Europe: Their fear prevented them from addressing the problems that could have removed that fear. (In this regard, as in so many others, Israel prefigured post-9/11 America.)

By the end of the 1970s, despite the vehement opposition of Israel, the PLO was increasingly recognized as the sole legitimate representative of the Palestinian people. During this period, Israeli representatives continued to insist that the PLO was a terrorist group pure and simple, dedicated to the destruction of Israel. The PLO did indeed issue contradictory statements about its position. But it was clearly inching toward explicit recognition of Israel's right to exist, although it had not yet arrived at that point. (Rejectionist Palestinian factions killed some Fatah leaders who dared speak of a two-state solution.) The larger Arab world, too, was moving in that direction. In 1981, Saudi Arabia floated the Fahd Plan, which proposed peace in exchange for an Israeli withdrawal from the West Bank and Gaza. Israel rejected the Saud plan as propaganda.

Meanwhile, Palestinian attacks from Lebanon against northern Israeli settlements continued. Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin and Ariel Sharon, now serving as defense minister, were determined to drive the PLO out of southern Lebanon once and for all, restore Christian dominance in Lebanon, and force the removal of Syrian troops from Lebanon. Seeking a pretext to invade Lebanon, they got one when Abu Nidal's group attempted to assassinate Israel's ambassador in London. (Abu Nidal, locked in a mortal struggle with Arafat and the PLO, probably intended the assassination to spur Israel to attack Arafat's organization.) Begin scoffed at the fact that the PLO was not involved: "They're all PLO. Abu Nidal, Abu Schmidal. We have to strike at the PLO." Begin regarded Arafat, "a two-legged beast," as the reincarnation of Hitler, driven by anti-Semitic hatred to seek the extermination of the Jews. When Israel bombed Beirut during the course of the invasion, Begin wrote to President Reagan that the destruction of Arafat's headquarters felt to him like he was destroying Hitler's bunker.

The Israeli invasion drove Arafat and his fighters into Beirut, which was then besieged and heavily attacked by Israeli forces. In the end, Arafat and about 14,000 Syrian and Palestinian fighters were evacuated under the protection of a multinational force, including American troops. The fighters relocated throughout the Arab world; Arafat and the PLO leadership moved to Tunisia, where they were to remain for years, until the Oslo peace talks led to the creation of the Palestinian Authority and his return to the occupied territories.

The most momentous event of the post-Lebanon years, the intifada, or uprising (literally, "shaking off"), took place without Arafat's involvement or backing. In 1987, Palestinians began an organized campaign of resistance throughout the occupied territories. Arafat and the PLO were marginalized by this grass-roots rebellion. The intifada had momentous political consequences. In 1988, trying to take advantage of the international sympathy created by the intifada, with its images of rock-throwing Palestinians fighting Israeli tanks, Arafat and the PLO officially recognized Israel's right to exist and called for a two-state solution. (The collapse of the Soviet Union, long a patron of Arab states and the Palestinians, also drove Arafat and the PLO toward moderation.) That same year, Jordan's King Hussein cut his ties with the West Bank, removing the "Jordanian option" favored by Israeli leaders as a convenient solution to the Palestinian problem. The United States finally extended a measure of diplomatic recognition to the PLO. Further diplomatic attempts failed, however, and the low-level conflict in the occupied territories continued.

The big breakthrough -- or what appeared to a big breakthrough -- came in 1993, with the signing of the Oslo Accords. Following secret back-channel negotiations between Palestinian and Israeli officials, Israel agreed for the first time to allow a Palestinian government. Areas of Palestinian self-rule were established in the West Bank and Gaza, with plans for step-by-step expansion of Palestinian autonomy later. Arafat made a triumphant return to Gaza in 1994, taking control of the newly established Palestinian Authority. International hopes for a lasting peace ran high.

But the Oslo years proved a bitter disappointment to both sides. Critics like the Palestinian-American professor Edward Said rejected Oslo because it failed to address the explosive final-status issues like settlements, Jerusalem and refugees, relying on a process of building mutual trust. Other Palestinians defended Oslo as a necessary, if flawed, first step. In the event, the lives of ordinary Palestinians failed to improve, Israel continued to build settlements, and the Palestinian Authority functioned more as a patronage machine than a viable government. Arafat and the PLO, which cracked down on Hamas and Islamic Jihad radicals, were also increasingly seen as doing Israel's police work for it while getting nothing in return.

Caught in a characteristic bind, Arafat responded, as always, by equivocating and tacking: giving a red, then a yellow light to terrorists to preserve his standing with Palestinians, while hoping that economic improvements and the cessation of Israeli settlements would build the PLO's status. For many Israelis, the dramatic increase in terror attacks in 1994-96, which Arafat was either unwilling or unable to control, proved that the entire Oslo process had been a terrible mistake. For Palestinians, the culprit was the continued building of Israeli settlements, especially around East Jerusalem, which they regarded as prima facie evidence of Israeli bad faith. One Palestinian leader said the building of settlements had the same effect on Palestinians that bus bombings did on Israelis.

The 1995 assassination of Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin by a Jewish extremist was a severe personal blow to Arafat and had major political consequences in Israel. A series of Hamas terror attacks, and a widespread Israeli conviction that the Oslo years had only brought more terrorism, helped lead to the election of hard-liner Benyamin Netanyahu over the moderate Shimon Peres. Netanyahu was unwilling to continue with the Oslo process, which spelled out trading pieces of West Bank land for peace. Arafat's domestic position was growing weaker, as increasing numbers of Palestinians, angered by Israeli closures that choked their ability to work, and by the incompetence and corruption of the Palestinian Authority, began turning to Hamas. This then intensified Israeli resistance to Oslo, which then created more Palestinian hardliners. It was a vicious circle that no one -- not the Israelis, Arafat or the Americans -- were able to break.

The final chapter of Arafat's saga was at once the most hopeful and the bleakest: The failed Camp David/Taba talks and the Al-Aqsa intifada that broke out afterward. Even the participants at those talks cannot agree on what happened or who bears ultimate responsibility for the collapse of what was the most promising attempt to defuse the world's most dangerous crisis. Whoever was to blame, the Al-Aqsa intifada that followed (which was not instigated by Arafat), and the election of Ariel Sharon, father of the settlement movement, quickly led to a disastrous deterioration on the ground. Unlike the first intifada, which was characterized by civil disobedience and limited violence, Al-Aqsa was a lethal uprising, with Palestinian guns and bombs replacing stones. The 9/11 terror attacks against the United States and the election of the right-wing administration of George W. Bush dealt Arafat and the Palestinian cause a severe blow. Bush and his administration linked the al-Qaida attacks against the U.S. with Palestinian attacks against Israel. Bush refused to deal with Arafat, seeing him as a terrorist, and gave Sharon a free hand to retaliate militarily against the Palestinians while continuing to expand and consolidate Israeli settlements in the occupied territories.

This was the bleak situation at the time of Arafat's death -- one for which the Palestinian leader, along with his Israeli and American counterparts, bore his measure of responsibility. The leader who embodied the dreams of his people, brought them international recognition and achieved many victories for them, is also the leader who repeatedly failed them. Until the Palestinian-Israeli conflict is finally resolved, Arafat's legacy will be a giant question mark, carved in stone.

Shares