Subcomandante Insurgente Marcos, the charismatic, masked leader of the Zapatista movement for indigenous rights in Mexico, is hard at work on his most unorthodox manifesto yet: a crime novel. With the help of one of the genre's most popular authors, Pablo Ignacio Taibo II, "Muertos Incomodos" ("Awkward Deaths") is being serialized in Mexico City's brazenly leftist daily La Jornada and will soon be published, in book form, in eight countries. But does Marcos truly believe this novela policiaca will further his cause, or is this the pulp hobby of a revolutionary in twilight? What's the relevance of political fiction, anyway?

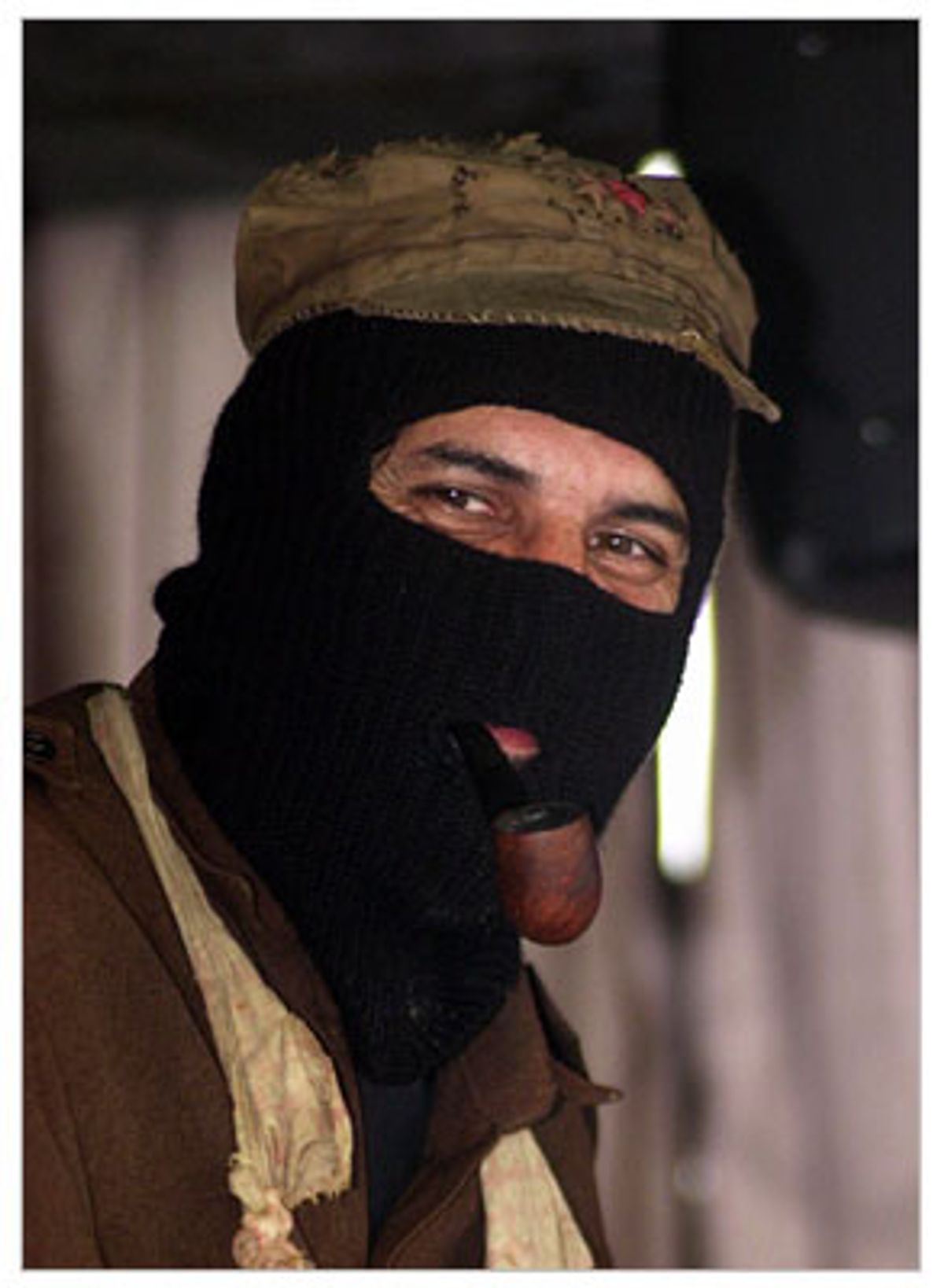

More than a decade ago, the former philosophy professor dropped out of bourgeois society to take up the cause of Mexico's indigenous peoples, appearing in public only in full fatigues and a black ski mask, a macho pipe dangling from his mouth. Not Indian himself, he's transformed himself into "el enmascarado," the Lone Ranger of the jungles of Chiapas, an almost mythic intellectual fighter for social and economic reform. The romantic prince of anticapitalismo, his communiqués often take the form of grandiloquent poems: He calls the Zapatista rebels "the voice that arms itself to be heard/ the face that hides itself to be seen."

Lyricism and dramatic flair aside, Marcos has managed to get things done: He organized, motivated and garnered much-needed media attention (and public sympathy) for the plight of the millions of wildly exploited Indian farmers in the southeast. But with the passing of an Indian-rights law by Mexico's Congress in 2001 -- based on the Zapatistas' demands but eviscerated by a government friendly to big business -- the movement lost its steam. That same year, President Vicente Fox decreased the number of federal troops stationed in Chiapas, and the worst abuses against the Zapatista communities, including torture and arson, seemed to have subsided. The revolution had lost its sense of urgency.

At which point it appears Marcos worried, wondering, What next? How to make the movement seem vital again?

This brings us to the Subcomandante's foray into the literary world. In early December, he sent a note to Taibo, whose clever detective novels are big sellers in Latin America and Europe (think Grisham meets García Márquez), asking him to collaborate on a novel. A plan was hatched: The two agreed to alternate chapters, with Marcos mailing his pages from his mountain hideaway to the author's Mexico City pad. Within no time, La Jornada was printing the installments in its Sunday edition.

With little in common in lifestyle -- one organizes lit festivals while the other organizes guerrillas -- the odd couple do share the bond of flagrantly left-wing politics. Each has spoken out against government corruption and the vast socioeconomic inequalities in Mexico, and La Jornada has published most of Marcos' numerous communiqués and Taibo's political essays. "The publication of a novel in chapters revives an old tradition," remarks La Jornada editorial page editor Luis Hernández, who printed the first chapter of "Muertos Incomodos" on Dec. 5. "The newspaper was interested from the first moment. And we will publish as many chapters as the writers choose to write." The novel tells the intertwining stories of Marcos' protagonist, Zapatista operative Elías Contreras, who takes his orders from the pipe-smoking Zapatista leader known (of course) as Subcomandante Insurgente Marcos, and Héctor Belascoarán Shayne, the private detective at the heart of Taibo's previous series. Contreras is sent on assignment to Mexico City to meet with Belascoarán, who is investigating cryptic answering-machine messages being left by a leftist assassinated years ago.

"I asked myself, when I received this invitation, Have you ever in your life said no to a challenge?" explains Taibo, who put down years of work on a Pancho Villa biography to take up the novel. "I think Marcos is a wise guy, so I said, 'Let's jump.'"

But what's in it for Marcos?

Imagine the elusive revolutionary, the faceless rebel who once marched into Mexico City to speak to a crowd of 100,000, now finding himself with hardly an audience at all. Cloistered away in the jungle, he's growing restless. The phrase "cultural irrelevance" darts through his mind. No grand initiatives on the calendar, he thumbs through his duffle bags stuffed with Marx, Durkheim ... and several dog-eared Taibo paperbacks. The self-styled soldier turns from writing propaganda to penning genre lit, his collaboration with Taibo his version of the Iowa Writers' Workshop. (We are, after all, talking about a man who's led seminars in aesthetics.)

Amusing as the image is, it touches on something: What does it mean for a revolutionary to turn to literature? Beyond his "poetic" communiqués, Marcos has anthologized short stories, publishing "Our Word Is Our Weapon" at the height of the movement, when the Zapatistas awaited their hearing with Congress in 2001. And "el Sup," of course, is not the first radical leader to do so: take Saddam Hussein's allegorical novels that pit glorious Iraq against the corrupt Western powers (not to mention his more recent poetry from a maximum-security cell). Can such scribblings amount to more than ego fodder? Or are they the ultimate symptom of a revolutionary in winter, nostalgic for the good old days, spinning a fantasy to make up for his lame-duck reality?

But let's, for a moment, give Marcos the benefit of the doubt and assume that he is a true believer in the suggestive powers of fiction, in the possibility that a crime novel may be the most effective means of insinuating propaganda into the popular imagination. Can fiction still pull off such a feat? Marcos is one of the great propagandists of our time, and, according to Hernández, La Jornada quickly garnered a 25 percent rise in its Sunday readership with the inception of "Muertos Incomodos." The New York Times and the Guardian reported on the literary project as international news.

But while packed with venomous references to neoliberalismo, globalization, and those who "disappeared" during the anti-leftist "dirty war" of the '70s, the wrench in the book is literary: It's dismal. Its chapter-by-chapter production leaves the story without clear structure and intent, and it's as uneven as the talents of its authors, with Taibo's installments miles ahead. Despite his painfully clear aspirations, Marcos -- who has at this point written chapters 1, 3, 5, 7 and 9 (out this coming Sunday) -- is no fiction writer. Rather than flesh out his hero, Marcos tends to prefer introducing new characters just for the hell of it, as with the brief appearance of a sassy transvestite mechanic. Generally speaking, his prose reads as if it has been written by a philosophy professor turned resistance leader, which is to say it begs for an editor. To put it kindly.

Taibo, in contrast, understands his genre inside out. He alternates concision with Chandler-esque detective-speak. Most important, he understands noir humor -- hence the low-level government official with a limping, cigarette-swallowing dog. With relish, Taibo's P.I. describes himself as "left-wing, but without having read Marx at 16, without having been to enough demonstrations, and without having a poster of Che Guevara in my house." Ironically, Taibo's descriptions of the political landscape are also more evocative than Marcos', and his political farce is that much more outrageous -- as when he writes in a subplot suggesting that "bin Laden" is actually a taco maker turned porn actor named Juancho set up in a studio in Burbank, Calif. For Taibo, political content goes hand in hand with crime writing: "When you write mystery and crime, it's always political," he remarks, "because crime deals with abuse of power in this country. So if [the Zapatistas] want to send a special message through the novel, then let it come -- I am sending messages through the novel, too."

It must be said that with the publication of each successive chapter, Marcos seems to be learning from the seasoned veteran Taibo. His structure has become sharper, his tone more playful. "It's a game, a friendly game," says Taibo with a laugh. "It's like, 'Let's make it more difficult, please. Now you have to jump from the third-floor window instead of the second.' We don't know where it will go, and in this case there's no way to go back and revise."

Perhaps most interesting about the Marcos-Taibo partnership is how much it has in common with the bestselling pairing of Tim LaHaye and Jerry B. Jenkins, coauthors of the blockbuster "Left Behind" series of apocalyptic Christian novels. If Marcos' intention in co-writing "Muertos Incomodos" is to revitalize the Zapatista movement, then it couldn't hurt for him to take a tip from these American evangelicals. The two divide their duties between LaHaye's bombastic interpretation of the Book of Revelation and Jenkins' innate understanding of pop fiction. They're an equally odd couple -- LaHaye the 70-something radical theologian and founder of the Moral Majority, and Jenkins the 50-ish sports and mystery writer whose favorite author is Stephen King -- but they have their faith in common.

When LaHaye decided to write a novel imagining the Second Coming in contemporary times, his agent introduced him to Jenkins, and the two came up with a work method: For each book, LaHaye sends Jenkins an explicit outline of plot based on scripture, which Jenkins then weaves into the fictional story of edgy journalist Buck Williams and pilot Rayford Steele, left on earth to somehow survive the rule of the Antichrist. (LaHaye's far-right views are also worked in neatly: anti-abortion, anti-Catholic, anti-United Nations.) Since 1995, their brand of collaboration has produced a total of 12 novels, with yet another due in March. The formula has sold a staggering 62 million books to date, outselling titans like Grisham and King.

On one hand, writing a novel is the most benign pursuit a person can undertake -- paling in comparison, certainly, with facing down some 70,000 federal troops in a cornfield with black-market machine guns, as the Zapatistas have done. But when you consider that LaHaye and Jenkins have managed to sell their tracts to tens of millions of people, the endeavor becomes a little less innocent. Of course, a Marxist movement originating in the mountains of Mexico may never have the same potential audience as fundamentalist Christianity does in the States, but there are signs of an appeal beyond Chiapas. Proceeds from the sales of international rights to "Muertos Incomodos" are already in the six figures, with the profits going to Enlace Civil, a Zapatista-affiliated group, to promote the health and education of the people of Chiapas. Perhaps it's time for Marcos to give up playing the auteur and consider playing LaHaye to Taibo's Jenkins -- for the sake of the millions of indigenous Mexicans he claims to represent.

Shares