When her daughter was on the verge of adolescence, journalist Karen Stabiner was warned by an acquaintance that "life between a mother and a teenage girl gets as bad as it once was good." At the time, Stabiner's daughter, Sarah, was an affectionate 10-year-old who made daily declarations of love for her mom and wrapped herself around her mother's shoulders "like a vine." Could it be true that soon she would suddenly turn into an insecure, angry parent hater? The kind of disaffected girl whom Stabiner read so much about in the newspaper and saw portrayed on TV and in the movies?

Stabiner was suspicious -- but frightened nonetheless. So she decided to turn her reporter's eye on her daughter and document her entry into adolescence. Stabiner, the author of four nonfiction books, spent three years observing Sarah and her friends, taking daily notes on everything from the tone of voice they used with their parents to the way the girls interacted at birthday parties. She interviewed other mothers (most of whom she knew personally), delved into research on adolescent girls and spoke with experts in adolescent psychology, all in an effort to uncover what really happens to girls when they hit their teens.

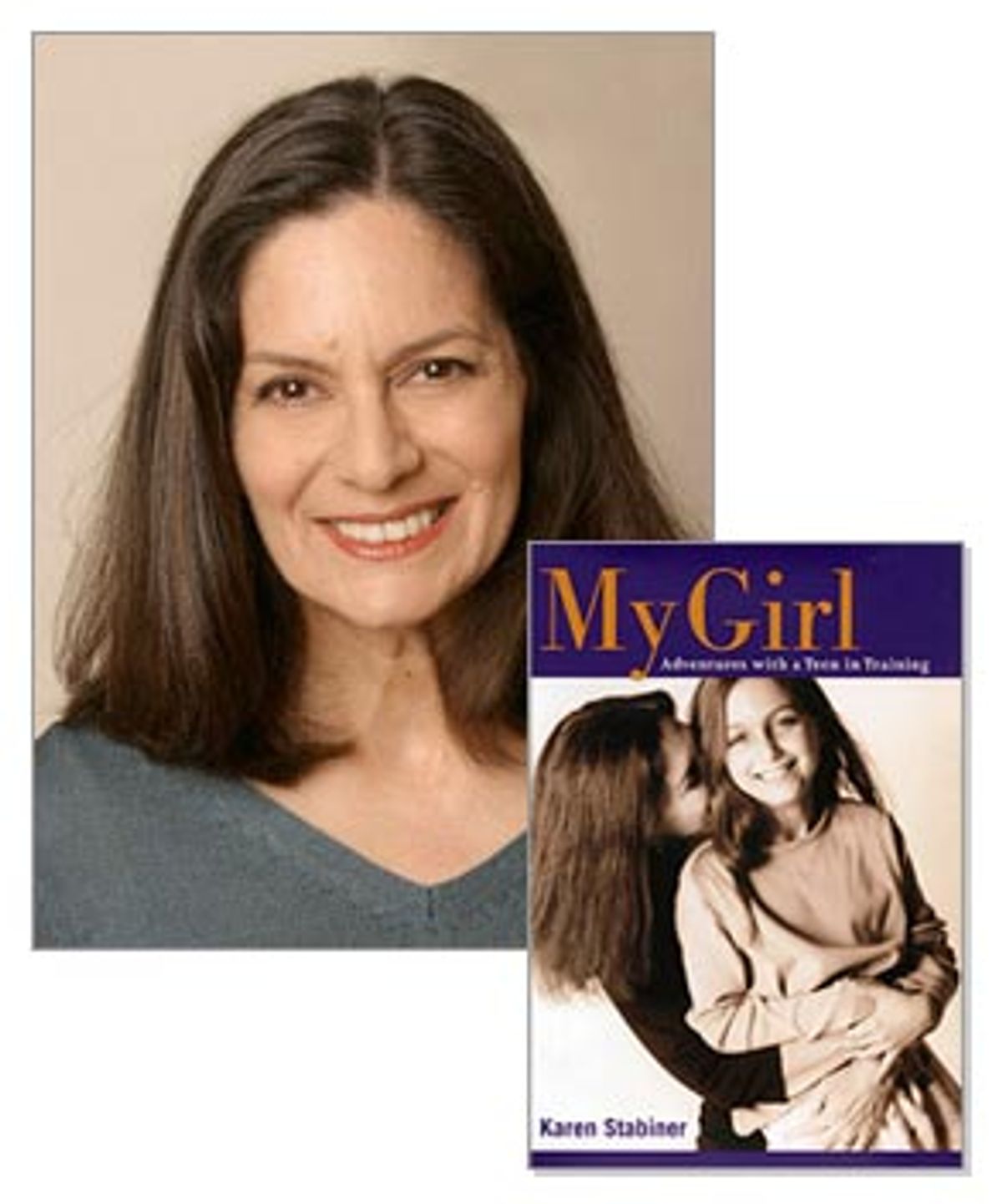

The resulting book, "My Girl: Adventures With a Teen in Training," is a touching exploration of what it's like to be the mother of a preteen girl. Nervous parents who had nightmares after watching "Thirteen" will be relieved to learn that Sarah made it through her early teen years without acquiring a wicked best friend, an eating disorder, a drug addiction, a baby or a pierced tongue. Stabiner asserts that her experience with her daughter -- mostly smooth, though punctuated by small triumphs and disappointments -- is the norm. Sure, Sarah experienced some difficulties with navigating the coolness hierarchy at her middle school, and she occasionally snapped when she felt like her mom was being overbearing or clingy, but overall, she was just fine. In fact, many times in this journal-like book, the anxious mother is the one who seems to need the self-esteem boosting, the reassurance and the encouragement.

Stabiner spoke with Salon by phone from her Santa Monica, Calif., home about how stereotypes can obscure the joys of raising a daughter, why girls are fed up with how they're portrayed in the media -- and why moms should be, too.

Around the time Sarah turned 10, you started to worry that life would change for the worse once she hit her teens. What did you fear might happen?

I thought to myself, if I'm to believe what I see in our culture, then she's going to turn into Linda Blair from "The Exorcist" overnight. She'll be mean to her peers, she'll develop every diagnosable disorder, she'll want to dress like a slut. She's going to stop talking to [me] -- and even if she does talk to [me], it's only going to [be to] say something nasty. She's going to be involved in sex, drugs and rock 'n' roll. I mean, rock 'n' roll's fine, but the other two aren't.

And you think the culture spurred your feelings of dread?

All you have to do is look at titles of books and magazine articles. There was this rash of books that came out in the spring and summer of 2002 with incendiary titles such as "Fast Girls: Teenage Tribes and the Myth of the Slut." The movie "Thirteen" is another good example. If you believe the headlines, you should be worried. But I also got a lot of it from other mothers of older girls. There was this horrific Greek chorus of doomsayers. The happier we seemed, the more they wanted it to end.

Why do you think these moms said these things?

I think there are three groups of women who believe the hype about "bad girls": women who did have bad experiences themselves, women who have sons -- "Oh, you poor thing. Little Freddy/Joe/Bob is so much easier than I imagine a girl would be" -- and women who don't even have children. They'd heard all this stuff and couldn't figure out why I was being so blind to it.

Why are we so prone to believe the worst about girls?

It is a hard time to be a girl in this culture. I'm not saying all girls are happy. There are girls today facing profound and genuine problems. Where we've gotten into trouble is [when] we've taken those stories, which are real, and extrapolated them to all girls. If you actually go back and look at stats and the research, most girls do not suffer from the kind of stuff we hear about all the time. Ninety-seven percent of girls do not have a diagnosable eating disorder. Eighty-five percent don't have food issues -- or don't have reported food issues. Fewer teen girls are having intercourse than they did 10 years ago. Illicit drug use is going down. More girls are participating in sports than their mothers did. More are going to college. You don't hear about that. You hear a disproportionate amount about those in trouble.

I think moms tend to be more worried about this, because they were teenage girls once. Part of what's so hypocritical now is that we were not angels, yet we expect our daughters to be not only angels but executive angels. I was recently speaking to a group of women, and I said, "Raise your hand if your daughter talked back to you today." Every hand went up. I said, "You may only put your hand down if you never talked back to your mother." Every hand stayed up. There is a strange double standard these days where everything our daughters do is wrong.

So you had a hunch that the media and the fear-mongering moms were blowing things out of proportion.

The thing that really got me focused on this was the girls at the all-girls school I wrote about in my last book. While working on that, I hung around with five girls, seniors in high school, and spent a lot of time with their families. I was like, "Look at all these wonderful girls! They're not monsters."

There was a girl in that book who was at school when a speaker came to talk about girls and body image. This woman was a very well respected cultural historian. We adults loved the speaker's effort to take a historical look at adolescent girls, and we loved all the examples of how society -- through advertising and media -- pressured girls to embrace a pretty rigid aesthetic. We thought she'd help turn the girls into savvier consumers, and provide them with a defense against the onslaught of media messages they see every day that tell them how they ought to look.

But after the talk, this one girl was very angry. She was like, "How dare you come to this school full of girls who want to make a vibrant life for themselves and assume we are anything less than marvelous?" She and other girls took [the speaker's presentation] as an insult; they didn't like the suggestion that they were a bunch of sheep that were incapable of evaluating society on their own.

All the adults were fascinated by the girls' perspective. Sarah was 8 or 9 when I was working on that book, and the idea for "My Girl" came right off that one. I thought, "She's my daughter. Why would I want to embark on the most interesting and full-of-change part of her life assuming the worst? Why not assume the best and see what we get?"

Who was the speaker?

I'd rather not say.

How do you think negative stereotypes affect people's perceptions of their daughters?

There's a mother in the new book whose daughter is about to turn 13, and every time the girl opens her mouth the mom is like, "Oh my goodness, look at her. I can't believe I'm going to have a teenager in the house! I don't know what I'm going to do!" Can you get any more unfair than that? Many of us with decent daughters are missing the good stuff because we're so programmed to notice and respond to the bad stuff. Forget notice -- we now anticipate it! Girls feel like they have to work 14 times as hard in order to make us feel like they're OK.

According to the book, Sarah has made it through ages 10 to 14 without encountering any problems. No drop in self-esteem; no change in grades; no issues with sex, drugs, alcohol; no all-consuming desire to rebel against her parents --

Sarah's not perfect. She is a regular kid. She talks back, she drops her clothes on the floor, she makes mistakes. She is a real girl.

Are you as close now as you used to be?

We are close in a totally different way. We're both very aware that she needs me less than she used to. I think the pressure is on me at the moment to yield gracefully, to know when I need to be the parent and when I need to let her take care of herself.

The book is more of a memoir of motherhood than a chronicle of pre-adolescence. Did you think there would be so much of you in the book when you took on the project?

I was really interested in the mom's role in all of this. Mothers and daughters have a very intense relationship. I wanted to see what [adolescence] was going to do to her, and I also wanted to see what it was going to do me. They're so tied up together.

How did Sarah feel about you writing this book?

People ask me that all the time. Many assume that she would not be happy about this. It was that same assumption all over again: Girls are trouble; this is going to cause problems. I don't think these people were even thinking about Sarah and me, specifically. They'd bought the stereotype about polarized moms and daughters, and they couldn't imagine us communicating enough to fill a book. Maybe a small pamphlet, but a whole book? Full of what -- "Where'd you go?" "Out." "What'd you do?" "Nothing." It's what we fear and expect, and the notion of an alternative brings out the skepticism in everybody.

What I heard from Sarah and her friends was that girls are starting to resent the way they're portrayed in this culture. They're like, "Enough already." Sarah liked the idea of a reappraisal that would attempt to give girls their due. She was really excited to see the first copies of the books, and she seems very happy with the result.

In the book, you mention several psychologists and scholars who have written about adolescent girls, including Judith Rich Harris, Lyn Mikel Brown, Carol Gilligan, Mary Pipher and Rosalind Wiseman. It sounds like you were suspicious of some of this work, especially Pipher's ideas that girls' self-esteem plummets as they hit adolescence.

I didn't make a conscious decision to take on anyone who has written about adolescent girls. I'm not here to say throw out all the books about "bad girls," girls who are having problems. They exist and they need the compassion and attention that we can give them.

But I also think we shouldn't assume that all girls are going to end up that way. When you look at the statistics, most girls are not going to have those problems.

[It's like what happened with] menopause. We used to think it was a living nightmare. The only data we had was from women who were in real distress. Their distress was real, but the vast majority of women were too busy living to report their problems. We never saw that population. That population didn't have a voice in the same way reasonable girls who are neither wretched nor perfect don't have a voice right now.

You admit that your small sampling "is no more statistically significant than all the bad-girl data, but it is no less true." If you really wanted to show the world that not all girls go bad, and that a troubled few get all the attention, why did you decide to make the book so autobiographical? Why not interview large numbers of mothers and daughters?

I felt there was enough research at the base of this to make it credible. I really believe a detailed story about one person carries a different kind of resonance than a story about lots of people. You get fewer numbers but more impact.

Yes, but you also set yourself up for skepticism, for people to say, "Well, that's just a small number of girls."

Here's my question for those skeptics: Why are you so eager not to believe this? If it's your kid, why are you so unwilling to entertain the notion that she's marvelous?

Sarah is an accomplished rider and has her own horse. To many people, equestrian sports are the domain of the rich and privileged. Do you worry that this will cause other moms to hold the book -- and your conclusions about happy teens -- at arm's length? Do you think people will say to themselves, "How could Sarah not grow up happy? She's lived a privileged life. She's one of the lucky ones."

It's the girls of the middle- and upper-middle class who often suffer the kinds of problems that we read about -- eating disorders, drug and alcohol abuse, the oral sex epidemic. But our sense of proportion about them -- It must be everyone! Everywhere! -- is so out of whack. If anything, Sarah's demographics make the message here even more urgent.

If you look through the bad-girl literature and watch the bad-girl movies, you usually see girls who have all the creature comforts. Since they don't have to deal with basic needs, they go looking for more imaginative ways to get into trouble. But the bad-girl cliché is just that. It doesn't pertain to all girls, or even to most girls, and I like the idea of Sarah and her pals standing up for the rest of our daughters.

Is this book your attempt to present a different spin on pre-adolescence?

There are other books that are oral histories of difficulty. There is no history of regularness, of reasonableness, or of the attempts to maintain a relationship. What I found when I started to ask around was that there were a lot of moms who never said anything about [the experience of raising their daughters] because their experience had been fine. They just didn't speak up because they didn't know that [women like me] needed reassurance.

When I ask women who have children what they thought of the book, they say they felt a tremendous amount of relief. They felt like they weren't crazy and alone. Or, if their daughters are younger, they feel the way I felt when I met those high school girls: "Oh my goodness, it's not going to be that bad." I hope that people will gain strength and encouragement from this.

Why did you choose to end the book with Sarah's 14th birthday? She doesn't even have her driver's license yet -- a milestone you referred to several times, with notable apprehension.

When I started the book and she was 10, people would say, "She's not 12 yet, just you wait." Then we'd get to 12, and they'd say, "Just wait until she's 13." No matter where I was, the only reason she was good was because we hadn't gotten to "bad" yet. Well, she's 15 and a half and we're fine, thank you. If the guillotine is still hanging over my head, the hinges are starting to rust. If you [as a parent] have "the end is nigh!" philosophy, you're going to miss everything.

Shares