Once again, George W. Bush finds himself confronting a nettlesome ethical and political debate that has intermittently dogged his presidency -- the fight over the future of embryonic stem cell research in America. Late last month, over the White House's strong objections, the House passed legislation to increase federal funding for the research, and the Senate looks certain to do the same in coming weeks. Religious conservatives vigorously oppose the stem cell bill and Bush has promised to veto it if it reaches his desk.

What's remarkable about Bush's stance is that just about every survey taken on the issue shows that all but the most ardent right-wingers support expanded funding for embryonic stem cell science. Yet Bush seems to have paid no political price for his restrictive policy. When he first dealt with the issue during his first year in office, he came up with a stem cell plan that pleased neither scientists nor moralists -- but it was quickly forgotten after 9/11. Stem cells again made a brief appearance in last year's campaign, when Ron Reagan, among many other Democrats, tried to drum up support for research at the Democratic National Convention. Obviously, the pleas didn't hurt Bush very much. Americans may have opposed his policy, but clearly stem cells weren't a deciding factor for many voters in November.

It's possible that Bush will once again dodge the stem cell bullet. He could veto this bill, keep the GOP rank and file from pursuing an embarrassing congressional override, and put the issue behind him, never to hurt him or his party's political fortunes again. If so, it may be thanks to publicity stunts like the one he staged the day the House passed the stem cell bill. Bush invited to the White House two dozen children who had been born from frozen embryos. He suggested that lawmakers who defy him on stem cells were actually working against these children's interests.

Now, those babies were adorable. And a cute baby goes a long way in defending a nearly indefensible public policy position, especially when the debate is as complex as the one surrounding stem cells.

Here, then, we present our guide to help you see through the fog created by Bush's publicity ploys: a thorough explainer on stem cell research, and the facts you'll need to follow the upcoming debate. To assemble this FAQ, we spoke to scientists, ethicists and political activists on both sides of the stem cell fight. We can't promise our efforts will lead to a more enlightened stem cell policy -- but perhaps, at least, we may have a debate on the science that's unimpeded by cheap publicity stunts.

Let's start with the current debate. What is the bill all about?

The Stem Cell Research Enhancement Act of 2005 (read the text here) would increase federal funding for scientific research on embryonic stem cells. Specifically, the bill would let the government pay for research on stem cell lines derived from embryos stored at in-vitro fertility clinics. Currently, under a policy put forward by President Bush, the government will only fund research on a very limited number of stem cell lines.

Wait, hold on. You're already losing me. "Stem cell lines"? Can you start with a short primer on stem cells? What are they?

Stem cells are what scientists describe as "undifferentiated" cells, meaning they have not yet specialized to perform specific functions in the body (like, for instance, acting as part of muscle tissue or blood or the nervous system.) They are found in the human body at any age -- in embryos, in fetuses, and in adults -- where they act as the root (or "stem") of all the cells that make up our tissues. In other words, all of our cells arise from stem cells.

OK. So why are scientists interested in them?

Such cells exhibit two important, unique properties. First, you can think of stem cells as immortal. When stem cells are removed from the body and studied in a lab, they can be made to indefinitely self-replicate, creating a pool of exact copies of themselves. One of these pools is called a "stem cell line" -- a practically limitless factory of stem cells.

Stem cells are also uniquely flexible; you can think of them as being essentially "programmable." Under the right conditions, scientists can coax a stem cell into becoming a specialized cell, a blood cell, a liver cell, a brain cell.

And how does that help us?

Well, taken together, these two features, self-replication and flexibility, make stem cells remarkable, almost magical things. Some scientists imagine stem cell lines someday serving as cellular "repair kits" for the body. If researchers can perfect the techniques to grow and direct stem cells into becoming specific kinds of body cells -- currently a very big, contentious "if" -- they foresee a future in which new, healthy cells can be created in a lab, and injected to replace diseased cells in the body. Stem cell therapy, scientists hope, may treat or cure a host of ailments beyond the reach of medicine today, including, to quote from the Web site of the International Society for Stem Cell Research, "Alzheimer's disease, cancer, Parkinson's disease, type-1 diabetes, spinal cord injury, stroke, burns, heart disease, osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis."

Well, that sounds great. Where's the controversy?

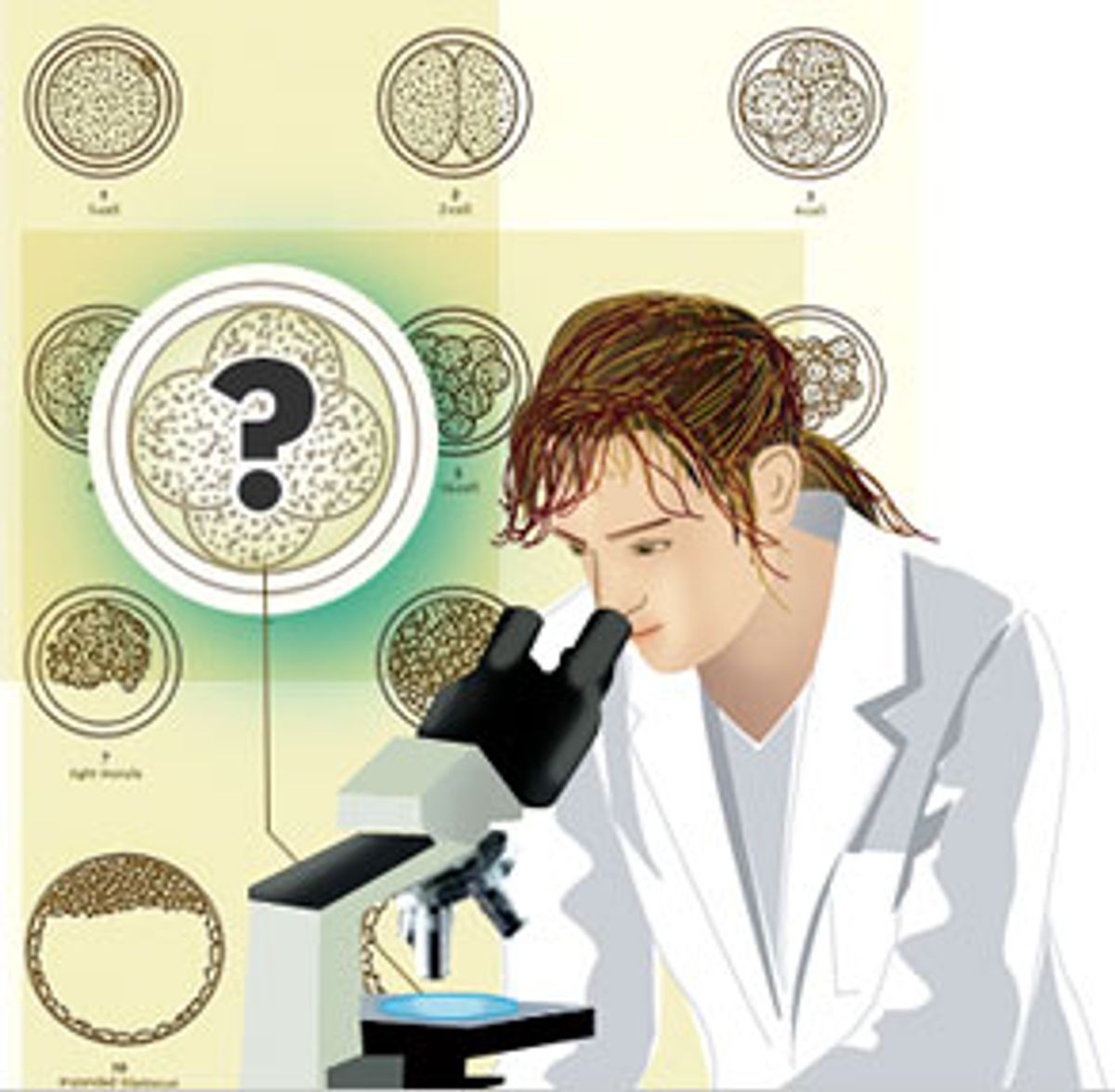

The ethical debate has to do with where we get the stem cells to use in therapy. Scientists have collected stem cells from umbilical cord blood, from fetal tissue, and from certain tissues -- like bone marrow -- in adults (and children). And in 1998, researchers developed a method to collect stem cells from human embryos -- these are called "embryonic stem cells." (An embryo, as we'll explain in more detail below, is the human body at its earliest stage of development; it is the product of the union of sperm and egg. You can see a neat visual chart of human development here.)

"Adult stem cells" -- that is, non-embryonic stem cells -- have proved beneficial in treatments for many diseases, mostly blood-related ailments such as leukemia. But many researchers believe that stem cells from embryos hold the most promise for eventually curing or treating some of our most pernicious diseases. That's because embryonic stem cells are considered more plastic -- that is, they can be turned into more kinds of body cells -- than those derived from, say, bone marrow in adults.

OK, so stem cells from embryos are considered more useful -- but they are also more controversial, right?

Right. That's because scientists derive stem cells from what's called the "inner cell mass" of the embryo, which is the part of the embryo that ultimately becomes the fetus. Therefore, when stem cells are removed from the embryo, the embryo is destroyed.

People who believe that "life" begins at conception, and that an embryo is morally indistinguishable from a human being, believe that it deserves the same protection as you or me. To these people, destroying an embryo to get stem cells that may treat or cure diseases that afflict fully developed human beings is not an acceptable trade-off.

Ah -- it seems we're in familiar territory here, the age-old question of when life begins, and at what point one can consider a clump of cells to have become a human being.

Yes, that's true. But you should note that the players aren't exactly the same as in the debate surrounding other "culture-of-life" fights, including abortion. As we'll explain in a minute, there are several biological and philosophical reasons to believe that an embryo is fundamentally different, and therefore deserving of a different ethical standard, from a fetus or a fully developed human being. Even many pro-life lawmakers recognize this difference, which is why so many Republicans defied their leaders to vote with Democrats on the Stem Cell Research Enhancement Act.

What's important in this debate, though, is that leading Republicans, including Senate Majority Leader Bill Frist, House Majority Leader Tom Delay, and President Bush, think of embryos as human beings. Bush calls embryos "real human lives," and he says they should not be destroyed. DeLay's rhetoric is even sharper. In a speech on the House floor opposing the latest bill, DeLay declared that harvesting stem cells from embryos constituted "the dismemberment of living, distinct human beings for the purposes of medical experimentation." He added: "The best that can be said about embryonic stem cell research is that it is scientific exploration into the potential benefits of killing human beings."

OK, I can understand that kind of language from Tom DeLay. But I seem to remember Bush being more open to compromise on stem cells. Am I wrong?

You're right that there is a perception that Bush has taken a reasonable middle-ground position on stem cells. It is a perception that the White House has sought to cultivate. On Aug. 9, 2001, after what he described as a period of intense inquiry and soul-searching during his first summer in office, Bush announced his stem cell policy in a televised speech to the nation. Federal money, he said then, would only be used to fund research on stem cells that had been collected from embryos prior to the date of his speech. His justification was that for those cells, derived from embryos that had already been destroyed, "the life and death decision has already been made." But research on stem cells derived from embryos destroyed after Aug. 9, 2001, would not be eligible for federal funding, Bush said.

This limitation, he insisted, would not greatly harm stem cell science. Bush explained that more than 60 stem cell lines had been created by that date -- enough stem cells, he believed, to allow scientists to "explore the promise and potential of stem cell research."

Something tells me he wasn't right about that.

He wasn't. Despite Bush's assurances, his policy has harmed the science. First, what Bush said about the number of stem cell lines that his policy would allow scientists receiving federal grants to work on was false. Instead of more than 60, there were only 22 stem cell lines created before Aug. 9, 2001, now available to scientists. These lines -- what some researchers call the "presidential lines" -- have proved useful to scientists, but largely "for basic research," Evan Snyder, a stem cell scientist at the Burnham Institute in La Jolla, Calif., told Salon last year.

Because the federally funded cells were prepared in the early days of stem cell research, many scientists are starting to "outgrow" them now, Snyder said. Indeed, it's unlikely that the cells currently approved for funding can be used in any actual treatment for human beings. Because pre-Aug. 9 stem cells were harvested mostly for research purposes and not for clinical medicine, they were kept alive using "feeder cells" from mice; scientists worry, therefore, that the presidential stem cells carry mouse viruses that would make them dangerous for human treatments.

Stem cells that were harvested after 2001 -- and which scientists can study using non-federal and private funding -- don't suffer the same problems. Newer stem cells can be prepared "without touching animal materials," Snyder said. "We've developed lines that are not killed by antibiotics. We can even grow cells that don't touch any biologics at all." But under Bush's policy, no research on these advanced stem cells can be funded with government money.

And this is the maddening thing about the Bush policy, opponents say. The president frequently touts the fact that his administration has given more than $50 million to fund embryonic stem cell research in the last four years. What he doesn't say, though, is that under his plan, the government's money has only gone for work on stem cells that scientists already know cannot be used in treatments to help human beings.

So that's where this new bill comes in, right? The supporters basically want the government to fund research on new stem cells?

Right. Supporters of the current bill -- it's called Castle-DeGette in the House, after its chief sponsors, Republican Mike Castle and Democrat Diana DeGette -- point out that there are more than 400,000 human embryos currently stored in freezers at in-vitro fertilization (IVF) clinics across the land, and that many of these can be used for stem cells.

Wait. Where did these embryos come from, and how did they get put on ice?

The embryos in storage were created as part of routine fertility treatments. It's common in IVF medicine for a doctor to fertilize several of a woman's eggs, creating multiple fertilized embryos, and then to implant only a few of those embryos in the woman's uterus in the hopes of producing a baby. The rest of the embryos -- the ones not implanted, which are usually the ones that doctors determine are not growing normally, or simply just don't look right -- are "cryopreserved," or frozen.

Though procedures vary from clinic to clinic, IVF patients are often free to determine what should happen to their frozen embryos, and most elect to do nothing at all with them -- to keep the embryos frozen indefinitely, in the event they may need the embryos again. According to a 2003 study by the RAND Corp., the vast majority of the 400,000 frozen embryos currently in storage are being saved by patients for possible future pregnancy attempts. A small number of embryos -- 2.3 percent -- have been slated to be donated to other expectant parents (what some on the right call "embryo adoption," and what fertility doctors call "embryo donation"), and 2.2 percent are marked to be discarded. Another small portion -- 2.8 percent, or 11,000 frozen embryos -- have been slated to be donated to scientific research.

RAND estimates that if all these 11,000 embryos marked for research were harvested for stem cells, scientists would derive about 275 new stem cell lines to work with -- an order of magnitude greater than the 22 stem cell lines currently eligible for funding.

There's one important fact to note about Castle-DeGette. The legislation would not fund the actual harvesting of stem cells from these IVF embryos; that process, which destroys the embryo, would still need to be funded with private or non-federal money (for example, from biotech firms, universities, or state governments). But if Castle-DeGette passes, all subsequent research on the stem cell lines derived from the frozen embryos would be eligible for federal funding.

So just to be clear, this bill would apply only to embryos that IVF patients don't want anymore -- embryos that would otherwise be discarded?

Yes. As written, the bill requires fertility patients to consent in writing to donation of their embryos; the patients must state that the embryos would have been discarded if they hadn't been donated for research.

And that's what makes the bill so appealing to lawmakers, even to those who identify themselves as "pro-life." One of these is Jim Langevin, a Rhode Island Democrat who often votes with Republicans on abortion issues, and who was paralyzed at 16 when an accidentally discharged bullet severed his spinal cord. "To me, being pro-life also means fighting for policies that will eliminate pain and suffering and help people enjoy longer, healthier lives," Langevin said on the House floor. "And to me, support for embryonic stem cell research is entirely consistent with that position. What could be more life-affirming than using what otherwise would be discarded to save, extend, and improve countless lives?"

Many pro-lifers agree with that rationale. In the end, 50 Republicans, some who have been given stellar marks by anti-abortion groups, voted for the bill in the House. In the Senate, the bill is thought to have at least 58 supporters, and possibly more than 60 -- enough to override a presidential veto in that chamber. It is unclear, though, if there are enough votes in the House to override a veto.

OK -- and that's important because the president has vowed to veto this bill, right?

Right. And what's remarkable about his promise is that if he goes through with it, this would be his first exercise of his veto power. Bush explains his decision by making the same argument as others on the far right -- embryos are human beings, he says, and he'll exercise his veto to protect that firm moral line.

OK, so maybe it's time to talk about whether Bush is on solid ethical ground when he says embryos are human beings. Is an embryo, as Bush says, a "real human life"?

It's not an easy question to answer. Indeed, whether or not embryos are human beings has been one of the most contentious debates in bioethics during the past decade -- and in the end the decision would seem to be a highly personal, moral choice.

Ethicists who argue that embryos are not human beings point to their lack of development. Scientists collect stem cells from a four- or five-day-old embryo, called a blastocyst. An embryo at this stage is about a tenth of a millimeter in diameter, as wide as a cross-section of human hair. Seen through a microscope, the embryo is a ball of less than 200 cells displaying no recognizable features of humanness. A days-old embryo has not yet established a head-to-toe orientation, and it has no capacity to feel pain or any other sensation. An embryo at this stage has none of the specialized cells that make up the tissues in our bodies; the cells in such an embryo have not even begun to become body cells. In a mother's body, a four-day-old embryo would not yet have attached itself to her uterine wall; its viability would be far from assured.

There are also philosophical reasons to question the embryo's status. Does the embryo have a "soul"? Bioethicists note that if it does, it's not an individual soul, since an embryo at this stage has not yet reached the point where it might split in two to become twins. An embryo can't be thought of as an individual person, some ethicists say, since it may actually become two different people.

Those on the other side of the debate counter that their lack of development does not mean embryos are not human beings. As the President's Council on Bioethics' 2004 report on stem cell research explained, critics of embryonic stem cell research "suggest that it is dangerous to begin to assign moral worth on the basis of the presence or absence of particular capacities and features, and that instead we must recognize each member of our species from his or her earliest days as a human being deserving of dignified treatment."

In this view, embryos represent the possibility of a new human life, and so destroying an embryo destroys that possibility. Many opponents of Castle-DeGette make this point. "The embryos that were you and me were allowed to grow to become Congressmen, Congresswomen, police officers, factory workers, soldiers, government employees, lawyers, doctors, scientists," Bart Stupak, a Michigan Democrat, said during the debate in the House. "We were all embryos at one time. We were all allowed to grow."

Does Bush's position on stem cell research reflect strongly held personal beliefs?

Well, we have no way of knowing what Bush actually believes. It certainly is possible that he really thinks of embryos as deserving the same moral consideration as the rest of us.

The problem, though, is that Bush's position is intellectually and morally inconsistent. If Bush really thinks embryos are human beings, you'd think he would insist on protecting them in all circumstances. But he's not. And it would appear that the reason he's not is because if he did, the public wouldn't stand for it and he and the GOP would pay a steep political price.

What do you mean?

Take IVF medicine. Bush's belief that embryos are human beings stands in direct opposition to the way fertility medicine is currently practiced in the United States. IVF clinics treat embryos as "special tissues deserving of special respect," but not as human beings, says Sean Tipton, a spokesman for the American Society for Reproductive Medicine, which represents the nation's fertility clinics. After all, Tipton notes, "you don't put human beings in freezers."

If we were to treat embryos as human beings, IVF practice would need to be significantly altered. You would want to create only as many embryos as you were going to implant, and you'd never freeze them, and never discard them. Such restrictions would make IVF medicine more arduous for women, more expensive, and would likely reduce its rate of success. "The entire endeavor would be overall less effective," says Eleanor Nicoll, also of ASRM.

But Bush is not proposing such restrictions, is he?

No, he's not. And that's the point. If Bush really thinks that embryos are people, he'd want to make sure that IVF clinics, which treat embryos as tissues, would change their ways in order to reduce their dependence on creating, freezing and discarding extra embryos. But he's proposed no such rules, and has had generally positive words for the practice of IVF medicine. The babies at his press event the other day were, after all, conceived through IVF.

So does anyone on the right want to outlaw IVF medicine due to the way it treats embryos?

Not exactly. But there are some religious conservatives who do wish that the president and other Republicans would pursue stricter regulation of IVF clinics. Carrie Gordon Earll, the senior analyst for bioethics at James Dobson's Focus on the Family ministry, describes her group's position on fertility treatment this way: "IVF can be used by married couples responsibly, if they only create embryos that will be implanted. Ideally the parents should go back for further pregnancy attempts and make every effort to implant frozen embryos." The other option, Earll says, is "adoption" -- if IVF patients decide that they don't want to implant frozen embryos, they should donate them to another couple. "There isn't any reason," Earll says, "why we can't have life-affirming response to all of these questions." We shouldn't ever have to throw away embryos or use them for research, she says.

Earll hopes lawmakers will pass such regulations on IVF medicine, but she understands that they're unlikely to do so. In the United States, IVF medicine is popular and uncontroversial, and has led so far to more than 250,000 births. Going after fertility treatments wouldn't appear to be a very good move for the "culture-of-life" Republican party.

"Ideally we don't want to see any embryos destroyed," Earll says. "But ideally I think we should have world peace. Just because you see a problem doesn't mean there's the political ability to change it."

So do you think that Bush actually realizes that IVF medicine is "killing" embryos, but he's not criticizing the practice because of politics? Or does he just not understand that IVF medicine leads to discarded embryos?

Well, we don't really know what Bush thinks about IVF. Bush dodged the question at a recent press conference. But as far as we can tell he's never once criticized IVF clinics for their routine practices of freezing and destroying embryos, practices he'd have to conclude are immoral, and which the right wants him to speak out against. So it would appear, then, that in the case of IVF medicine, Bush is putting politics -- i.e., the popularity of IVF -- above his supposed moral belief that embryos are inviolable.

And Matthew Yglesias of the American Prospect points out another area where Bush puts politics over embryos: Bush doesn't support a ban on embryo destruction in the United States. He only opposes federal funding of embryo destruction, and of research on stem cells derived from those embryos. But in most U.S. states anyone with state or private money is free to destroy an embryo and work on stem cells from that embryo, and Bush is OK with that. He knows embryos are being killed, and that stem cells from those embryos are being experimented upon, but he doesn't mind, because the government's not paying.

Of course, it would be politically costly for the president to advocate a total ban on stem cell research. But again, that's the point. If you believed that embryos are human beings, and if you believed that human beings were being killed, you would move to protect them -- or at least speak out in their favor -- even if there's a political cost to it. Bush hasn't done that, and he won't advocate banning embryo destruction, or all embryonic stem cell research. Indeed, at the Republican convention last year, when a few religious conservatives attempted to insert a plank in the party platform calling for a ban on all embryonic stem cell research, leading Republicans, on the White House's authority, fought the measure, and it lost by a close vote. Bush says he believes that embryos are people, but if protecting them meant losing the presidency, he was willing to let them die.

It sounds like you're suggesting that Bush doesn't really believe embryos are people?

Again, there's no way to know what he thinks. But the point is that his actions don't reflect this belief. Except in the single case of his opposition to stem cell research, Bush acts as if there are in fact differences between people and embryos, and that some things are more important than embryos -- including politics.

And that's not really a bad thing. Arthur Caplan, the director of the University of Pennsylvania's Center for Bioethics, points out that treating embryos as human beings in public policy matters would lead to outcomes that border on the absurd. If you treat embryos as "real human lives," not only would you have to ban IVF and stem cell research, "but you'd also have to ban sex," Caplan says. That's because normal unprotected sex frequently leads to pregnancies that never progress beyond the first few days after conception. Sex leads to embryos, and embryos are lost all the time -- according to studies cited by the president's bioethics council, between 22 and 40 percent of all fertilized embryos are lost before fertilization even becomes clinically detectable.

It's not necessary to point out that nobody, not even the most ardent pro-lifer, mourns the loss of these embryos. We don't take any precautions, as a society, to try to save embryos created as a result of ordinary procreation. No Nobel Prize will ever be awarded to the doctor who spends a lifetime searching for a way to prevent all this unnecessary "death." Why not? Because even if some people say they do, we generally do not consider embryos equal to the rest of us. Our world simply does not operate by that principle.

Hmm. So are you saying that if Bush can recognize the political benefit of allowing IVF to go forward despite its destruction of embryos, he should also let stem cell research go forward even though it destroys embryos?

It's not only a political calculation. It's also an ethical calculation. Whether or not he recognizes it, Bush tolerates IVF medicine because he realizes its benefits -- giving normally infertile couples the chance to become parents -- outweigh its costs, namely the freezing and discarding of "spare" embryos. Stem cell research presents a similar cost-benefit picture: The cost of destroying embryos that would otherwise have been discarded are outweighed by the chance at treating or curing diseases that afflict tens or hundreds of thousands of people.

Indeed, as Scott Rosenberg pointed out in Salon several years ago, embryonic stem cell research actually presents a neat solution to the moral dilemma created by IVF medicine. IVF creates unwanted embryos, and stem cell research offers us a way to put those embryos to good use.

OK, but doesn't Bush say that he's got his own solution to the problem of unwanted embryos -- doesn't he say that parents should give them up for "adoption"?

Arthur Caplan, the University of Pennsylvania bioethicist, has this to say of Bush's idea that hundreds of thousands of extra embryos can become children to adoptive parents: "I've never heard a sillier, more inaccurate, more ideologically fueled claim about anything in all of biomedicine." And Caplan is right.

It's true that there have been some children -- about 80 -- born from spare embryos donated to couples who want to adopt and also experience pregnancy. But to present this as a way to prevent throwing away all embryos currently frozen is grossly misleading. For one thing, the vast majority of parents of embryos in freezers don't want to give them up for adoption. They're emotionally attached to those embryos, Caplan points out, and they don't like the idea of other people raising their genetic children. That's why, according to the RAND study of frozen IVF embryos, more patients have chosen to discard or donate embryos for research than to donate them to other couples.

Moreover, the embryos currently stored in IVF clinics are there for a reason: They didn't look right, and doctors chose to freeze them rather than implant them. Perhaps that's why, according to the Centers for Disease Control, the chances of a frozen embryo resulting in a live birth are significantly lower than those of a fresh embryo: Once transferred into a woman's uterus, only 24 percent of frozen embryos result in babies, compared to 34 percent for never-frozen embryos. And not only is there a strong chance that you won't get any children if you choose to "adopt" frozen embryos, there's also a chance that you'll have more kids than you wanted, since embryo implantation very rarely results in the birth of just one child.

We should note that, just as it is unclear whether all of the embryos in storage can become babies, it's also unclear whether the embryos could work for stem cell extraction. But ethicists say it's much more practical, and perhaps humane, to try to get stem cells from the embryos than to try to get babies from them. In fact, it's unreasonable to expect any large demand for embryo adoption. Does Bush really believe that hundreds of thousands of women and couples who want kids will opt for this route -- to choose a process that rarely produces children, that sometimes produces more than one child, and that is, to boot, physically taxing and expensive? Caplan calls that expectation absurd.

And rather than selling them on this crapshoot, wouldn't it be more "pro-life" of Bush to suggest that childless couples choose traditional adoption? "We have 500,000 kids in foster care in this country," Rep. DeGette told Salon. "If the ultra right wing is so concerned maybe they might want to look out for kids who are already born."

But if it's so obviously absurd, so pie-in-the-sky, why is Bush pushing embryo adoption at all?

Because it lets him stage events in which he kisses babies. In the end that's what you've got to chalk it up to: Bush's policy on stem cell research is so inconsistent that even most people in his own party don't agree with him on it. After the election last year, the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation, which strongly supports embryonic stem cell research, asked a polling firm to conduct a survey of Bush voters' attitudes toward stem cell research. By a 52 to 42 percent margin, the Bush voters supported obtaining stem cells from embryos at IVF clinics that would be otherwise be discarded. Polls show independents and Democrats to be even more supportive.

By suggesting that every embryo harvested for stem cells represents a lost baby, Bush is attempting to move his uphill fight on stem cells to much more reliable political terrain -- the abortion debate. And indeed, many on the right see this fight as intimately tied to abortion, and groups like the National Right to Life Committee have warned lawmakers that any votes for embryonic stem cell research will be considered pro-abortion votes.

"This is part of not being able to give an inch on abortion," Caplan says. The right worries that by allowing embryo destruction, even for a good cause, they'd be making a hole in their argument that life begins at the instant of conception. Allowing stem cell research "threatens a consistency that is easier to defend" in the abortion debate, Caplan says.

So will it work? Will Bush manage to ride out this political storm by kissing babies?

He may. But if the bill passes the Senate -- where a vote has not yet been scheduled -- Bush is certain to face the kind of tough political choice that challenges even the P.R. power of adorable infants. That's why many supporters of embryonic stem cell research hold out hope that Bush will eventually see the light.

"It would be a grave error," says Rep. DeGette, "for his first veto to be of a bill that could lead to cures for tens of thousands of Americans."

Shares