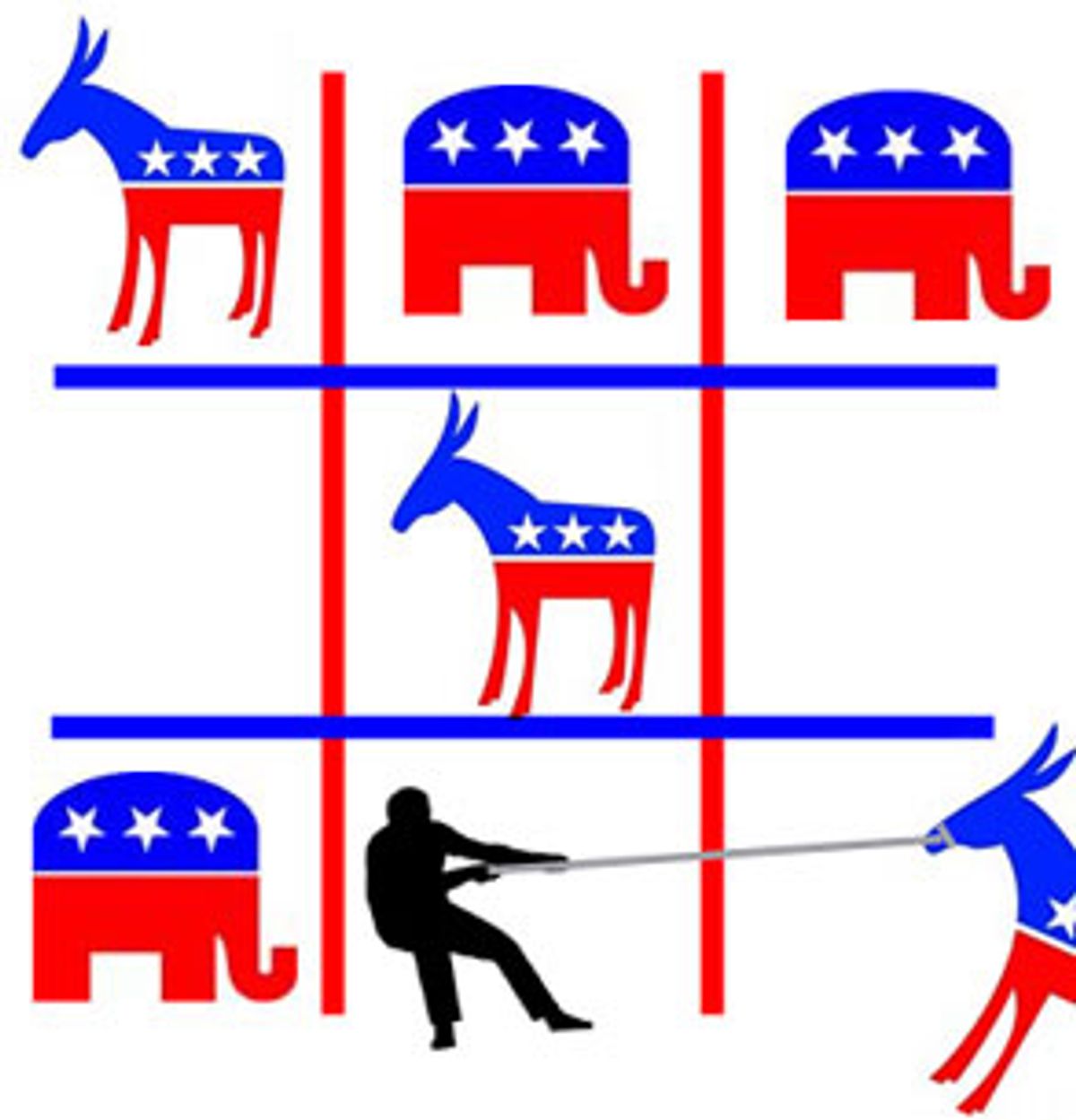

Half a century ago, Republican Sen. Robert Taft said the duty of the opposition was to oppose. Republicans were arguing the same line in 1994. Two months before the midterm elections that year, a bitter game of legislative chicken had ensued. The Republicans were filibustering a campaign-finance bill, one of the few items standing on President Clinton's legislative agenda. Amid an all-night session, as cots were set up and the theatrics began, Democratic Senate Majority Leader George Mitchell was frustrated. His party controlled Washington but couldn't pass meager campaign-finance reform. The Republican minority, Mitchell lamented, was "unprecedentedly obstructionist."

Come Election Day 1994, the obstructionists prevailed. Republicans took control of the House for the first time in four decades, and the Senate for the first time in eight years. More than a decade later, Democrats are borrowing from the Republican playbook.

As Democrats regroup from the electoral drubbing of 2004, they intend to portray Republicans as they themselves were cast a decade ago: a majority corrupted by political hubris gone awry. If a unifying strategic theme can be found among Democrats as they prepare for midterm elections, it is their intention to run as the alternative to what they claim is Republican legislative overreach and abuse. They'll "absolutely" run on their refusal to capitulate to Republican policies, House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi, D-Calif., declared in an interview. But compared with the Republicans of 1994, she said, "We have a stronger case."

Democrats are relying on the congressional equivalent of turnabout being fair play. And President Bush has taken notice: "On issue after issue, they stand for nothing except obstruction," he said of the Democrats at a GOP fundraiser this week. What a difference a term makes. The Democratic willingness to compromise that marked Bush's first term is no more. Most clearly, on the president's signature second-term issue, the partial privatization of Social Security, Democrats are almost bellicose in their opposition. "It's not dead yet," Pelosi said. "We have to stay focused on taking that down."

Democrats are also hoping to take down the nomination of conservative John Bolton to become the U.S. ambassador at the United Nations; they've waged a fight against legislation to make Bush's tax cuts permanent. And as the fight over judicial nominations gets hotter, Democrats gathered what political capital they could to retain their right to filibuster. "Right now," Pelosi said, "the issues climate and the ethics climate are very conducive to success for the Democrats."

"Conducive to success" is about as bold as Pelosi will get. But beneath the guarded language, Democrats are almost giddy. Whereas presidential elections place emphasis on the candidates, midterm elections are believed to be a referendum on the status quo.

Veteran Democratic strategist Bob Shrum, in what amounted to his first extended interview since the 2004 presidential election, said the Republicans are exactly where Democrats want them. "I think the contours of the landscape are such that you have a president whose major domestic initiative, Social Security, is in terrible if not terminal trouble," he said. "You have the cessation of judicial wars and satisfying the right wing. And I think the country is saying, why aren't they doing something about education, healthcare, the economy, and Iraq, the things that really matter in our lives?"

The midterm elections may be more than a year away, but Shrum insists, "We are gaining long-term traction." To be sure, recent developments have given Democrats leverage in their role as the opposition. Polls show that about six in 10 Americans now disapprove of the way Bush is handling the U.S. economy and the war in Iraq. Multiple polls, from Pew to CBS News, show the president's approval rating at record lows for his administration, bobbing just above 40 percent. Ethical questions surrounding Majority Leader Tom DeLay, R-Texas, have offered Democrats reams of material in making the case for Republican abuse of power. Democratic advertising already emphasizes the ethical imbroglios surrounding DeLay.

In Bush's push for the partial privatization of Social Security, Democrats echo the Republican opposition to Clinton's first-term healthcare plan, arguing that unified opposition to the majority's alleged abuse is a viable stand in its own right. "Social Security really has become a gift that President Bush has given us. He went to a place he wasn't prepared to go," Pelosi said.

Democrats intend to put this "gift" and others to good use in 2006. They will cite the GOP's efforts to undermine the judicial branch in the Terri Schiavo case as emblematic of Republican legislative overreach. They will cite General Motors' recent announcement that it intends to lay off 25,000 American workers, amid an ever-widening chasm between the richest and poorest Americans, while gas prices remain at record levels, as examples of an out-of-touch Republican Party.

And with more than 40 million Americans without health insurance, the minority party remains optimistic that healthcare is the "kind of issue that Democrats can rally on," former Sen. Carol Moseley Braun of Illinois said in an interview.

Sen. Mel Martinez, R-Fla., has reportedly joined calls for the United States to consider closing the controversial prison at Guantánamo Bay, describing it as an "icon for bad stories" and declaring that "it's not very American, by the way, to be holding people indefinitely." The Downing Street memo adds mortar to the case that the Bush administration was determined to go to war despite misgivings over intelligence.

Such revelations have led the House member who renamed French fries "freedom fries" -- because of France's opposition to the Iraq war -- to reconsider his support for the invasion. Rep. Walter Jones, R-N.C., recently told ABC News that the facts compel him to conclude that the war in Iraq was waged under false pretenses.

Democrats are wagering that while the public's misgivings over the Iraq war didn't defeat Bush in 2004, eroding support for Bush's Iraq policy may help the minority party in 2006. Fewer Americans, 42 percent, support the war today than ever before, according to the Gallup Organization. "The election is over and [Americans] are seeing some of these things with the air clear. They see that troops are dying, that the violence continues, and that we are not safer as a country," Pelosi said.

But will all of this add up to Democratic victories next year?

Pelosi doesn't expect her party to repeat the Republican gains of 1994. But she says the current climate "is making it far easier for us to do the three R's -- recruiting candidates, raising money and rapid response on what the Republicans are doing."

And yet the obstacles are higher. For one, legislative redistricting has made the advantages of incumbency greater. With little more than a dozen House districts clearly competitive next year, Democrats have a steep climb ahead. In the Senate, Democrats have more seats to defend while also vacating three of the four open seats, leaving the upper chamber likely to remain under Republican control.

Despite the terrain, Democrats paint a party confident that large inroads can be made in Congress in 2006, with the hope of taking the reins of power in 2008. "We were at the bottom," Shrum said. "We are a quarter of the way up the hill. People say, why aren't they at the summit? Well, you don't get to the summit of the hill, you don't get the election results, until you get to next November."

For Democrats to make a large gain in Congress next year, Shrum argues that they will "have to make sure we don't warn our candidates" to be overly temperate and shy away from blunt rhetoric. "I believe we too often did in 2002," he added. "The institutional bureaucracy of the party was warning candidates to be very cautious and careful in what they said. And I think that hurt in a number of places."

Whether it's blunt rhetoric, or just different rhetoric, Democrats know they must show not only what they stand against but also what they stand for. "We need to redefine our message and speak more confidently about values," New Mexico Gov. Bill Richardson, a Democrat, told Salon. "We need to expand the definition of values: the right to healthcare, the right to eliminate poverty, the right have a good education for every child."

While congressional Democrats will rely on their role as the opposition to define themselves, a national grassroots effort is afoot to emphasize populist themes in recasting Democrats as a values-based party. "Our problem is not of the heart or of the head; it's of the communication," Pelosi said. "It is not about using biblical terms in our speeches, or telling them how faithful we are; it's about how values are reflected in public policy."

In the hope of reframing the Democratic agenda, the Democratic National Committee under Howard Dean is focusing on so-called values voters. At the DNC executive meeting last Saturday in Washington, strategist Cornell Belcher told the 64 members that Democrats have "been painted as anti-religion," but that "the Republicans in Congress and this White House are moving in a direction that, in fact, faith voters didn't mandate for them to move."

Following Belcher, DNC chairman Howard Dean told the committee that "if voters understand what we believe in, we are going to win."

"We have not spoken about moral values in this party for a long time," Dean said, speaking with the passion that won him the DNC chair. "The truth is, we're Democrats because of our moral values. It's a moral value to make sure that kids don't go to bed hungry at night. It is a moral value to pay off debt, not add to it. It is a moral value to take care of senior citizens who have been struggling throughout their working life and to guarantee decent Social Security income."

Belcher and Shrum both argue that Democrats must soon redefine themselves on what could be called a "neopopulism" that doesn't oppose wealth but advocates policies that empower the working and middle classes. "We are in the process of doing that," Pelosi said. "We will be pivoting on that; we have that in the works. But right now the focus is on the Bush Social Security plan, it's on Iraq, it's on the deficit."

Republicans will certainly attempt to discredit Democrats trying to woo voters on populist rhetoric. As the Democrats did in 1994, Republicans are hammering Democrats today as little more than a legislative wrench. Last week in a statement, House Speaker Dennis Hastert, R-Ill., said, "Democratic leaders must be living in their own fantasy land to believe that obstructing progress will do anything to help the American people."

Richardson, the New Mexico governor, says Democrats must articulate their own plan for progress. "Sometimes, I believe, we are a bit headstrong in criticism of the Republicans without offering initiatives of our own," he said. Though partisans may differ on whether Democrats' "obstructionist" actions are best for voters, nonaligned political analysts believe it is tactically best for the Democratic Party.

"It is preferable and desirable to have a positive agenda, but I think it is absolutely necessary as the out party to make the election about the in party," said Stu Rothenberg, of the nonpartisan Rothenberg Political Report. "The Republicans in 1994 blocked Democratic initiatives and complained about gridlock. They also already had negative stuff, such as the Clinton healthcare plan, and it worked pretty well. The atmospherics are right for a Democratic year in 2006. The voters are dissatisfied with the direction of the country and not particularly pleased with the president."

Neither are voters happy with Congress as it stands under Republican control. The Gallup Organization's most recent polling found that 59 percent of Americans disapprove of the Republican-controlled Congress, levels unseen since President Bush took office. Nonetheless, voters' frustration remains short of Americans' perception of Congress in the summer of 1993. By July of that year, fully 65 percent of voters disapproved of the Democratic Congress. The poor approval ratings held steady for about a year, until by October 1994, as Election Day neared, fully 70 percent of Americans disapproved of how Democrats were running Congress.

Poor opinion of Congress in 1994 translated into a 54-seat Republican gain. The GOP took control of House for the first time since 1952. More telling, of the 34 incumbents who lost their seats in 1994, all were Democrats.

Democratic aspirations for similar success depend on "branding," as Pelosi put it.

Moseley Braun remains concerned that her party has not found the message to coalesce voters. "There is not a unifying principle that we could come up with, an alternative on Social Security, an alternative on healthcare, an alternative on even on pullout in Iraq," she said. "That has not gelled."

"We are working on the next step, to crystallize the message and into an even shorter message about who we are as Democrats, to brand us in that way," Pelosi said.

Back in New Mexico, Richardson explains that Democrats, above all, must work on this message. "We cannot just be a Washington-based party." Currently the chairman of the Democratic Governors' Association, Richardson insists he is not running for the presidency in 2008. Instead, he is focusing on the two gubernatorial races this year, as well as the staggering 36 contests in 2006.

History gives Richardson reason for optimism. The massive Republican congressional gains of 1994 were accompanied by an equally impressive 10 new Republican governorships.

"In 2005, we are really confident of winning New Jersey, and Virginia could go either way. Our objective in 2006 is to retain as many governors as we can and maybe add two or three," Richardson said. "But only if we focus on what our values are, as opposed to just being attack dogs, will we be better off, because the public is already disenchanted with the president and the Republican agenda."

It is this very disenchantment that Shrum believes places Democrats in a position to make some gains in 2006, if not large ones. Shrum insists Democrats will gain simply if Republicans stay their course. He believes that the steadfast image of Bush, which served him well in the presidential election -- a quality Democrats saw as intransigence -- will now serve to undermine the Bush administration and the Republican Congress. "Their only answer to failure is more of the same," Shrum said.

Today, the longtime Democratic strategist who has seen his candidates lose more presidential elections than he likes to recall, speculates that after a decade being the minority the Democratic Party has found its footing. But he is quick to add that although Democrats are united legislatively, the party's midterm candidates will not all hold the same positions on social policy, the war in Iraq and other issues. But to Shrum, that's par for a more pluralistic party.

"You never have a single-minded approach unless you have a president, or during a general election campaign when you have a nominee that people think has a chance to win. They all tend to sort of fall in line and not dissent from what that nominee is saying," Shrum said. "To say 'Democrats,' as though they were a single corporate entity directed by a centralized force, just isn't the case. The biggest uniter of Democrats, frankly, is George W. Bush."

Of course, that is the persistent irony of politics today. While Bush finds it harder to rally the nation behind his domestic agenda, his leadership continues to unite his opposition, as Republicans united against Bill Clinton a decade ago. And as long as the public disapproves of how the Republicans are steering the country, Shrum sees history on the Democrats' side.

"Every election where the out party gains in the midterm, and they usually gain, but where they gain in a substantial amount, is because there is something going on that people are profoundly dissatisfied with," he said.

Whether trouble for Bush will translate into Democratic success remains to be seen. But Shrum asserts that if Democrats are to come close to pulling off what the GOP did in 1994, "we have to recruit. We have to organize. We have to stand for something -- there have to be candidates who stand for something and convey that."

Shares