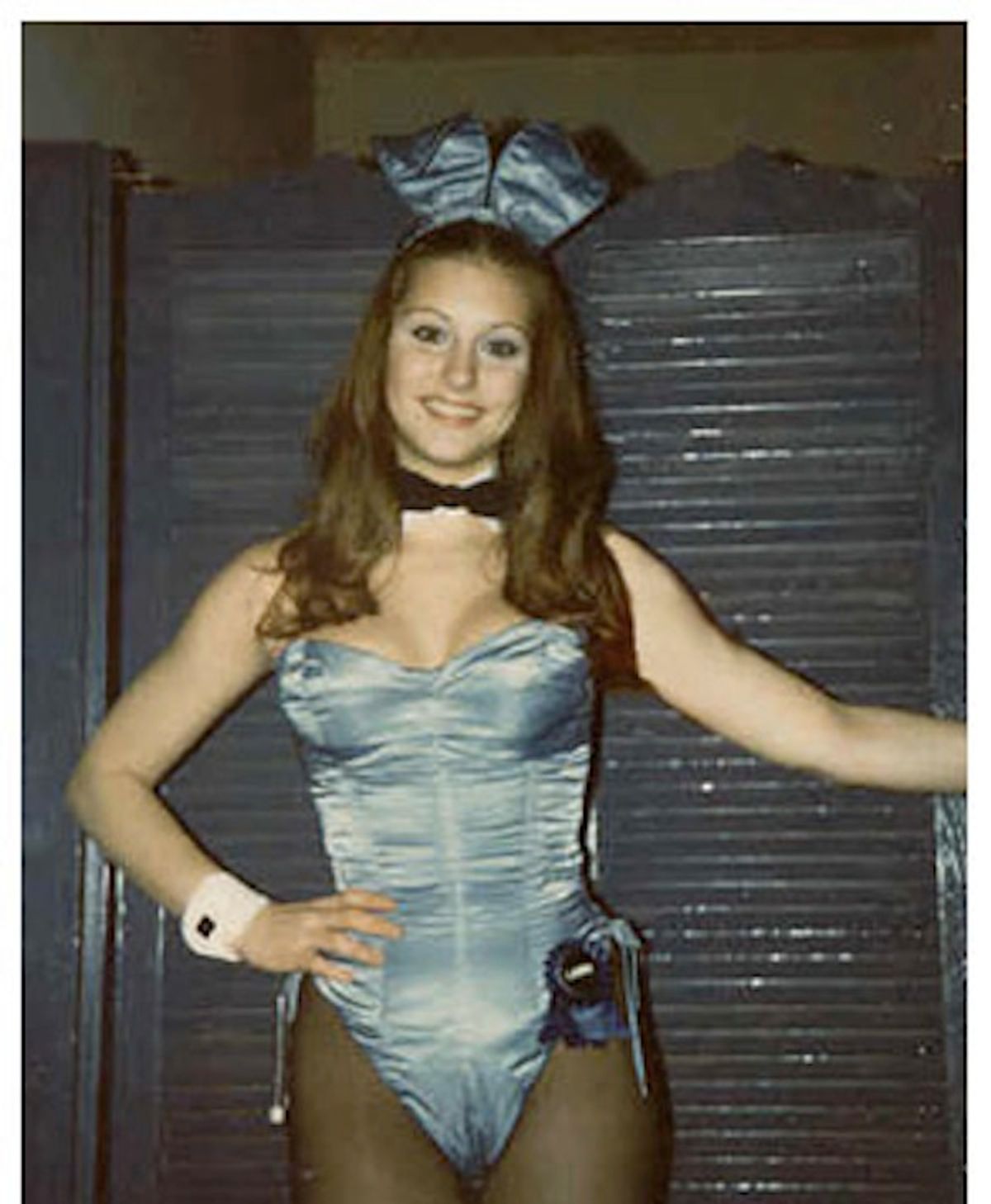

I stepped off the Braniff flight from Tulsa, Okla., at Moisant Field on Jan. 12, 1973, with $34 in my pocket and the promise of a job as a Bunny at the New Orleans Playboy Club. I was 19, with big, proud titties suitable for framing, and wearing enough Maybelline to sink a barge in the Industrial Canal. I didn't know it yet, but I would spend the next seven years in the City That Care Forgot. By the time I escaped its humid clutches, the Big Easy would fill me up and wring me dry.

I would marry a cop of easy virtue, pose nude in Hef's magazine, appear in some of the worst movies ever made and lie on the AstroTurf floor of the Superdome with former football star Paul Hornung, wondering why he had such bad cigarette breath.

The Playboy Club was on Iberville, in the French Quarter, an old carriage house tucked between Felix's Oyster Bar and Moran's Restaurant. Across the street was the Acme Oyster House, where I wolfed down drippy roast beef po' boys for months until a light bulb went off and I ordered one with oysters. Duh. Never went back to the roast beef.

Phone calls were a nickel and the streetcar was 15 cents. I'd get off work at 2 in the morning and take the streetcar up to Jackson Avenue and walk three blocks north to the room I rented with another Bunny, a girl who'd drifted down from Little Rock, Ark. This neighborhood was a bad place to be at high noon, much less after midnight, for a white girl alone. I was bulletproof. You tend to be, at 19, as long as your luck holds. Our room was $70 a month, with hot plate, mattress on the linoleum floor, skeleton keys to open any door in the spooky old ancient house.

There were 28 of us girls at the New Orleans Playboy Club, and we were girls, not women, make no mistake. I found out later that they called me "HG" behind my back, for "homegrown." Most everyone else was local, working class, with that heavy Yat accent. They had no illusions about what the job was: glorified cocktail waitressing in a birdcage costume, satin ears and killer shoes. I was starry-eyed and thought I'd hit the big time.

There was sad-eyed Wanda, the Gift Shop Bunny, whose name tag said "Un" because she was the Un-Bunny, and Geri the Door Bunny, outrageously beautiful, astonishingly dumb, whose boyfriend Sonny was a scary mobster. There were strict rules about not wearing jewelry "on the floor," but Geri's gasp-inducing diamond bracelet always peeked from beneath her Bunny cuffs, and no one said a word. Sonny packed heat.

Bunny Jade was the Pool Bunny, as in bumper, not splashing. A total Filipino babe with almond eyes and cascades of wild black hair, she was spared the horrors of waiting tables and got to play bumper pool all night long in the Playmate Bar. She'd bend over in her blood-red satin costume to take her shot and her enormous olive-skinned breasts would nearly flood onto the green felt, leaving her opponents in a state of slack-jawed wonder. Jade always won. Later, she began to put on a rather alarming amount of weight, and Viola, the wardrobe mistress, had to keep letting out her costumes. "Girl, you are getting fat!" Jade would laugh.

They paid us 90 cents an hour. We declared pennies on the dollar in tips. My first year I made $10,700, not bad back then for a kid just out of high school. Bunny Hellene, an old pro held up as our shining example of poise, grace and earning power, made $15,000 a year, according to Paige, the Bunny Mother. We neophytes could only nod dumbly and hope to aspire.

When we closed up shop for the night, we'd head way down Bourbon Street to Lucky Pierre's, a strange old place that used to be a whorehouse (and later burned to the ground). It stayed open till 6, maybe 7, and you could drink for a few hours and then have breakfast, eggs and ham, out in the courtyard, maybe a joint, washed down with a cold Dixie beer. By the time we staggered out, the first day workers would be up and heading to their lives, which we knew nothing, and cared nothing, about.

You might see Ruthie the Duck Girl, an old weird street person who wore bedraggled little-girl dresses and hair bows and had a wobbling line of ducks following her around. Sometimes she'd stop and turn around and talk to them like a mother to her errant children.

One night I walked in on a big-money card game above the Club Car Lounge, a favorite haunt because no tourists went there. Wandering around, I headed upstairs, crossed a large empty room and approached a door with a light under it. I pushed it open and instantly a tableful of fat, ugly, middle-aged men turned as one. Piles of money in the middle. Flashing pinky rings. Pockmarked skin. Scowls. Yikes. I fled back to my long-haired, 140-pound, Tulane-student boyfriend. We were gulping down our drinks when one of the men appeared at the back of the bar and looked around. Spotting us, he gave us a hard stare as if he was imprinting our faces on his twisted, sicko brain. Then he headed back upstairs. We never went back.

Six months after I started with Playboy, the magazine sent a photographer, Pompeo Posar, down on a scouting trip. Do test shots if you want to, Paige told us, but you're under no pressure. I signed right up. What better way to piss off my parents and make some real dough? Actually, it seemed rather thrilling. Pompeo was a charming bullshit artist. We got along fine. Taking my clothes off for him in a Victorian room at the Prince Conti Hotel was only difficult for about two minutes. Then it was, Aw, what the hell. He's seen this before. I wasn't expectng anything to come of it when Paige called me a few months later and said, They want you in Chicago.

For what?

Test shots for Playmate of the Month. A gatefold, dummy.

It sure sounded better than slinging bayou chicken and dirty rice from a steam table six nights a week.

I went up there many times over the ensuing months, sometimes staying at the Playboy Mansion for weeks before returning to New Orleans. I did finally make the centerfold in February 1975, was on the cover of that same issue, and did several more photo shoots for them, plus one more cover. I liked Chicago, but it seemed bland compared with New Orleans, and something always pulled me back.

I quit the club and began "modeling," a euphemism for, no, not that, but standing on my feet all day at the convention center in wigs and false eyelashes while extolling the virtues of a particular brand of heart-lung machine, or maybe a paint store. Salesmen from Waukegan, Ill., would stare at my breasts and ask me my name and if I knew any good restaurants in New Orleans. Burger King, I'd reply.

This led to a fabulous career in the movies. I'm sure you've seen me in "Mardi Gras Massacre," having my innards cut out by a guy wearing an Aztec mask. One Web site lists this gem as one of the worst movies ever, ever made. I'm proud. And remember "French Quarter," with Bruce Davison and Virginia Mayo? You don't? That's OK, Davison apparently doesn't either, because he won't list it among his credits. You can run but you can't hide, Brucie. I was there. You were in it, pal.

I had lines in those movies but only walk-ons in "Mandingo" and "Hard Times." Strange; I always played a prostitute. Didn't they see my shining thespian talents?

My acting career reached its zenith in a Miller Lite commercial shot at the Superdome. A bunch of us hotties dressed as cheerleaders had to tackle Paul Hornung and pile on top of him. Then he sort of popped his head out, looking rumpled and goofy, and said something like, "Less filling." Whatever. I was right next to him, on the bottom. Oomph. Golden Boy smoked and smelled like Hai Karate, Certs and Parliaments. At least he wasn't belching beer.

N'Awlins was a funky, funky town in the '70s, where the St. Patrick's Day Parade through the Irish Channel was more fun than Mardi Gras. It stopped at every corner bar. People fell off floats, laughing, to be carried away by the crowd in a spontaneous, delirious mosh pit. It was the era of WWL sportscaster and Old Yat Hap Glaudi, who started his segments with, "We goin' to go to da Saints!" Mafia chieftain Carlos Marcello was still alive and very much kicking, and could be found several nights a week holding court at Mosca's, the best restaurant in the whole world. Across the Huey Long Bridge and 20 miles from the Quarter, Mosca's was straight out of "The Godfather," an old family business with Mama in the kitchen and her boys out front, serving up baked oysters with garlic and masses of pasta and shrimp to the local power brokers.

Somewhere along the way I had gotten married to Eddie, a cop in the French Quarter. A product of the Lower Ninth Ward, he joined the force at 18 and was a flint-eyed veteran of 28 when I met him. He carried a chrome-plated Colt Python, drove a chocolate-brown Cadillac Eldorado and gambled heavily down in St. Bernard Parish. He bought me a fur coat. I thought he was terribly exciting. He'd bring me along to all-nighters at Benny's, a joint on the levee. I was required to sit silently for hours while Eddie twirled his gold wedding band and lost (or, occasionally, won) thousands at the card table. Benny was like 75 with about three teeth and had a 14-year-old girlfriend. This last fact struck no one but me as particularly odd or disgusting. Like everything else wild and evil in New Orleans, it was greeted with a shrug and a wink.

Eddie walked a beat in the Quarter. He and his partner took free meals and other stuff I only vaguely knew about, but they also "took care of their people," and it was an honest exchange to them. If you couldn't be bothered to be nice and slide over a bowl of free gumbo, well, when those kids threw a brick through your front window it might take a while longer for the po-lice to show up. Y'know? Eddie never paid for a drink that I saw, but then he didn't drink much. He'd rather talk, and listen. A good cop is a good listener.

He took me to the races at the Fairgrounds and taught me how to read the Daily Racing Form. He introduced me to the shady characters, shady ladies and shady ways of the Crescent City that I never would have tapped into otherwise. Without him, I never would have had a private room with a private waiter -- Joey Guera -- at Antoine's. Never would have had a real king cake at a family party, never would have gone fishing out of Empire, La., with so much beer aboard our little flotilla that we almost sank. And if we had, so what? There is nothing like a native New Orleanian.

We parted ways, eventually. I went down to Miami and he went back to being a bachelor. He moved out of our house on Pontchartrain Boulevard, five blocks from the 17th Street Canal that broke, and moved to a house on stilts, over the water, southeast of Slidell. He retired from the force as a lieutenant and was freelancing as a security man at "tittie bars" and rich people's houses Uptown on Audubon Place, last I heard.

I phoned him just before the eye of Katrina must have passed very near his house. I got his answering machine. Some silly nonsense about how he wasn't home, he was checking out the latest Saints trade. I said, Hey, you idiot, call me.

He hasn't called, and now I just get static when I dial the number. C'mon, Eddie, check in. Check in, dammit.

New Orleans is gone.

Shares