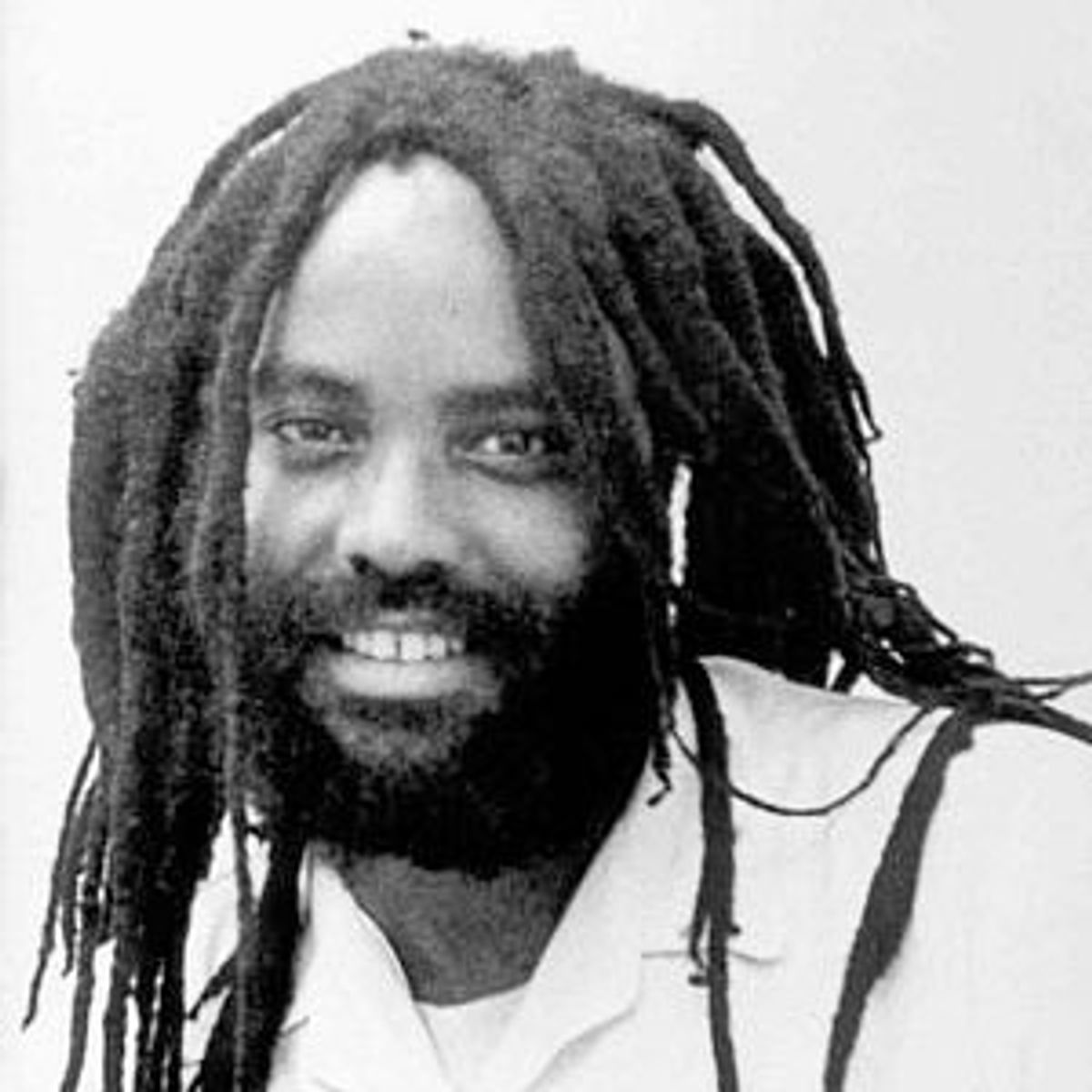

In a major development in the 24-year-old death penalty case of Philadelphia journalist and former Black Panther Mumia Abu-Jamal, a panel of three judges of the 3rd Circuit Court of Appeals issued a ruling Tuesday that Abu-Jamal can appeal his murder conviction on three separate grounds.

The court put the case, which has been in legal limbo for several years, on a "fast track," with the defense brief on the three claims scheduled to be filed Jan. 17.

The decision caught both the defense and the Philadelphia district attorney's office by surprise, because the appellate court had been compelled to consider only one possible avenue of appeal by Abu-Jamal. Pending before the same court is the district attorney's appeal of the 2001 lifting of Abu-Jamal's death sentence.

"Today we achieved a great victory in the campaign to win a new trial and the eventual freedom of Mumia," said a jubilant Robert Bryan, of San Francisco, who took over as lead attorney in Abu-Jamal's case in 2004.

Bryan said all three claims accepted for argument by the 3rd Circuit panel "are of enormous constitutional significance and go to the very essence of Mumia's right to a fair trial, due process of law, and equal protection of the law under the Fifth, Sixth and Fourteenth Amendments to the Constitution."

A spokeswoman for Philadelphia district attorney Lynn Abraham said her office had no comment on the court's announcement.

Back in December 2001, U.S. District Judge William Yohn overturned Abu-Jamal's death sentence, saying that the jury verdict form used in Abu-Jamal's trial had been flawed and that the judge's instructions to the jury had been confusing. That decision was immediately appealed by the district attorney's office. At the same time, Yohn had rejected all 20 of Abu-Jamal's claims concerning constitutional errors in his trial and state appeal process, certifying only one of those claims for appeal to the 3rd Circuit.

Under federal court rules, an appeals court is not required to consider any appeal from a defendant in a capital, or death penalty, case unless that appeal has been certified by a lower court judge.

The only appeal certified by Yohn for appeal was a claim by Abu-Jamal that the jury selection in his case had been racially biased because the prosecutor rejected 10 or 11 of 15 qualified black jurors, using peremptory challenges, for which no reason had to be given. The jury that ultimately convicted Abu-Jamal had only two black members, in a city that is 44 percent black.

The appellate court has agreed to hear defense arguments on the jury bias issue, which is known as a Batson claim.

But the 3rd Circuit also agreed to consider appeals on two other grounds. The first is a claim, rejected by Yohn and not certified for appeal, that the prosecutor in the case, Joseph McGill, had improperly attempted to reduce jurors' sense of responsibility during the so-called guilt phase of the trial, by telling them that any guilty verdict would be vetted later. As McGill put it in his trial summation, "If you find the defendant guilty, of course there would be appeal after appeal and perhaps there could be a reversal of the case, or whatever, so that may not be final." In other Pennsylvania cases, including one prosecuted by McGill, the 3rd Circuit has overturned capital-case convictions on the basis of the same wording used in trial summations.

The other uncertified defense appeal accepted for argument by the 3rd Circuit was a claim that the trial judge, the late Albert Sabo, was biased during the Post-Conviction Relief Act hearing. That hearing, which was held in 1995-96 to consider the validity of the facts presented at trial, as well as new evidence brought in by the defense, was controversial. At the time, the Philadelphia Inquirer stated in an editorial that the judge was displaying overt bias against Abu-Jamal.

Any one of the three claims, if upheld by the 3rd Circuit next year, could lead to a new trial for Abu-Jamal, who was convicted of the 1981 slaying of white police officer Daniel Faulkner. The most likely first action on upholding an appeal claim, however, would be an order sending the issue back to Judge Yohn for reconsideration, not an order for a new trial. A finding of bias on the part of Sabo could also lead to a reopening of the post-conviction hearing in a state court, legal experts say.

For Abu-Jamal, who has been in jail since December 9, 1981, and on Pennsylvania's death row since July 1982, the latest turn of events represents a major breakthrough. Up to now, no court at any level has accepted his arguments that his conviction was flawed. Judge Yohn's rejection of all the claims regarding the guilt phase of the 1982 trial had appeared to limit Abu-Jamal's options considerably.

Now Abu-Jamal has three avenues to challenge that conviction, two of which could lead directly to a new trial, and a third that could lead to a reconsideration of evidence or presentation of new evidence.

Meanwhile, the district attorney's appeal of the lifting of Abu-Jamal's death penalty is also moving forward, with a brief on that appeal scheduled to be filed with the 3rd Circuit panel on Feb. 16. If the lifting of his death sentence is upheld by the 3rd Circuit, and there is no order for a new trial, the district attorney will have 180 days to decide whether to leave Abu-Jamal sentenced to life without parole or to request a new trial on just the sentencing issue, in an effort to get a jury to impose a new death sentence. The appeals court could also overturn Yohn and order the death penalty reinstated.

None of that is likely to happen, however, while the court is hearing and ruling on appeals of the conviction itself.

There has been considerable turmoil in Abu-Jamal's case in recent years. In 1999, as his appeal was being considered by Judge Yohn, Abu-Jamal fired his attorneys, Leonard Weinglass and Daniel Williams. The cause of the dispute was a book, "Executing Justice," written by Williams, which was critical of both his client and of some of his supporters.

Abu-Jamal then hired two attorneys, Eliot Grossman and Marlene Kamish, neither of whom had any appellate experience in death penalty cases. They drove away many of his supporters with demands that they support Abu-Jamal's claim of absolute innocence, and their efforts to introduce into the case a man, Arnold Beverly, who claimed to be the "real killer" of Faulkner.

Abu-Jamal eventually dropped Grossman and Kamish from his case, the Beverly claim was abandoned, and Bryan was hired.

With the latest decision, a case that during the late 1990s aroused passions across the nation and around the globe, both among Abu-Jamal supporters and among police organizations and their supporters, is likely to be back in the headlines.

Shares